This story was originally published November 15, 2018. It was updated on August 21, 2019, to include information on arrests made in the case.

Just east of Central Avenue in downtown Phoenix, hundreds of people packed the sidewalks near Roosevelt and Third streets the night of October 5. They had gathered for First Friday, an art walk that helped the area dubbed Roosevelt Row garner national attention as one of the nation’s leading art districts. Some popped into galleries, looking at works by local artists. Others watched street-corner musicians or shopped artisan wares inside rows of white tents.

Few realized they were near a crime scene, or suspected that what transpired there before sunrise could cause ripple effects throughout the downtown arts scene for years to come.

That Friday, at about 3:30 a.m., two artists were murdered just west of Central Avenue, on the south side of Roosevelt Street near Third Avenue. Twenty-four-year-old Zachary Walter died shortly after being shot. Forty-one-year-old David Bessent was rushed to Banner – University Medical Center Phoenix with a single gunshot wound at the center of his forehead, just above his eyebrows.

Bessent died on Wednesday, October 10, after being taken off life support. He was an organ donor, according to his mother, Barbara Wert. She flew in from Michigan after learning he’d been shot. Three weeks later, on Tuesday, October 30, she went with a small group of Bessent’s friends to collect his ashes, contained in a black box that’s the size of her son’s palm.

Inside a flat silver case that belonged to Bessent, Wert keeps small strips of paper with copies of her son’s heart rhythm measured at the hospital. She gives them away in quiet moments to people affected by her son’s death, lamenting the fact that the organ couldn’t be donated.

“They couldn’t take his heart,” she says.

In reality, Bessent’s heart was transplanted years ago into the downtown arts community, where both he and Walter worked and lived.

The creative hub locals call RoRo wasn’t all that appealing back in the 1990s, when artists came looking for a place they could afford. It was blighted at the time, with a reputation for drug and gang violence. When the Five15 Arts collective opened its first gallery space in 2002, on Roosevelt Street east of Third Street, artists put corrugated metal over a front window with apparent bullet holes, and struggled to keep vagrants from wandering in.

Nowadays, city officials credit artists with helping to revitalize the area, by opening galleries, studios, and creative businesses that attract more people to the scene, where Bessent and Walter thrived in a culture-rich habitat. About five years ago, the ’hood hit a sweet spot. Artist-run spaces near the heart of RoRo thrived in a neighborhood-like setting, evolving organically without much outside interference.

People took notice. USA Today named Roosevelt Row one of the country’s top 10 art districts in 2014, and the American Planning Association named it one of the “15 Great Places in America” in 2015.

Then, the developers showed up.

Gentrification became a big concern in 2014, after Denver-based Baron Properties announced plans to build two multilevel apartment buildings at the intersection of Roosevelt and Third streets. Despite petitions and protests, the company demolished a building that used to house Phoenix’s first gay bar in March 2015. When a 1911 house faced a similar fate, Local First Arizona founder Kimber Lanning had it moved across the street so she could renovate and save it.

At that point, it looked like dominos, as well as the buildings, were falling in RoRo.

Artists gathered at funky community hubs like Jobot Coffee or The Lost Leaf on Fifth Street just off Roosevelt, decrying each new blow. Desert Viking, which recently moved from Chandler to Phoenix, bought a building on that corner in 2016, and several bungalows in the area, to create The Blocks of Roosevelt Row. Several galleries, a paint store popular with muralists, and an urban garden lost their spaces because of it. This year, the building that once housed a popular arts and music venue called The Firehouse was demolished to make way for yet another new development.

The Roosevelt Row landscape has undergone seismic shifts in recent years — reflected in myriad artworks by some of its most prolific artists. An iconic mural by Augustine Kofie and El Mac, an internationally renowned artist raised in Phoenix, became decor for patio dining at the former Flowers building, then defaced and left as is — signaling rampant disrespect for RoRo artists. And a carwash sporting a sombrero UFO mural by Lalo Cota was turned to rubble, then cleared to make way for a Starbucks at Roosevelt and Seventh Avenue.

The changes have prompted some to suggest the RoRo arts scene is dying. But no one expected the story to include murder.

Police records indicate that there have been 35 homicides since January 1, 2000, in the area bounded by Seventh Avenue and 12th Street, between McDowell Road and Van Buren Street. The number of murders peaked with nine in 2001 and eight in 2003, then dipped to zero for the years 2012 to 2014. There were two homicides in 2016, and one during the first half of this year.

Now, artists have lost two of their own.

Zachary Walter and David Bessent were also cooks at Jobot Coffee & Bar, a Roosevelt Row staple where creatives often gather late into the night. On October 5, they had finished their shift shortly before walking west together within the Roosevelt Row neighborhood.

Jobot sits on the southeast corner of Roosevelt and Third Street, just six blocks east of where the killings occurred. The restaurant is owned by John Sagasta. He relocated it from Fifth Street just south of Roosevelt Street in January 2017, after failed lease negotiations.

Sagasta had known Bessent for about a decade; Walter was relatively new to downtown Phoenix.

Walter was born in Colorado Springs, Colorado, the youngest of four brothers, but also lived in a quiet, rural part of Maine. Zachary loved nature, and climbing mountains. “He liked to hike up high,” his father, Daniel Walter, recalls. “He loved the city but he liked being outdoors and he was happiest when he was doing that stuff.”

Today, Daniel Walter wears a small vial with part of his son’s ashes around his neck. The family is planning to scatter some of them in Sedona.

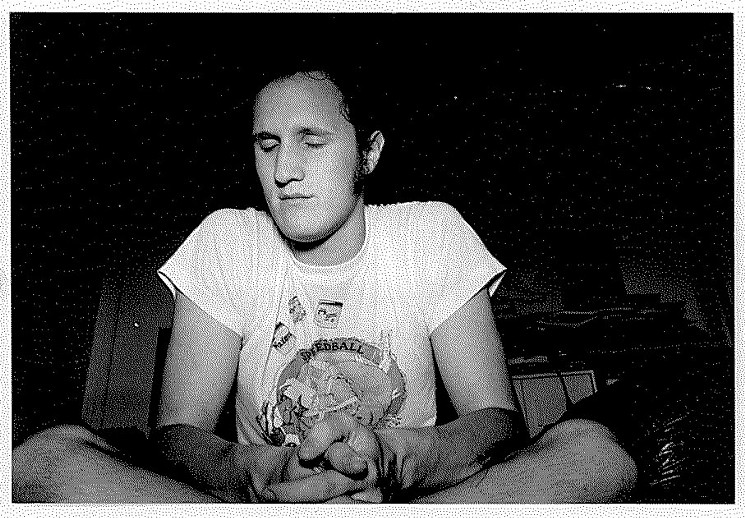

Zachary Walter had smooth, dirty blond hair that reached just past his shoulders, surrounding a fresh face and impish smile. Recently, he had been working with a friend to up his guitar skills. He owned three guitars, according to his dad. But he loved art and poetry, too. Walter was a regular at weekly drawing nights, where people would sometimes pass around journals so they could collaborate on group sketches. Bessent started the drawing nights years ago and they’ve brought all kinds of people together, from established artists like JB Snyder to people who’ve never drawn before.

For Lina Luna, sister of longtime artist Pablo Luna, the free gatherings have always been about fostering community. “Drawing nights have been a safe space for people who felt outcast, where they could be part of something positive,” she says. “They were making change through a medium that’s so beautiful, honest, and raw.”

The tradition is still a staple of Monday nights on the outdoor patio at Jobot, where friends remember Walter for his easygoing ways. “Zac was a really wholesome human who was very compassionate and empathetic, and a deep thinker,” says Brighton Casey Brick. They roomed together not far from the crime scene last summer, and she’s considered herself Walter’s best friend for several years now.

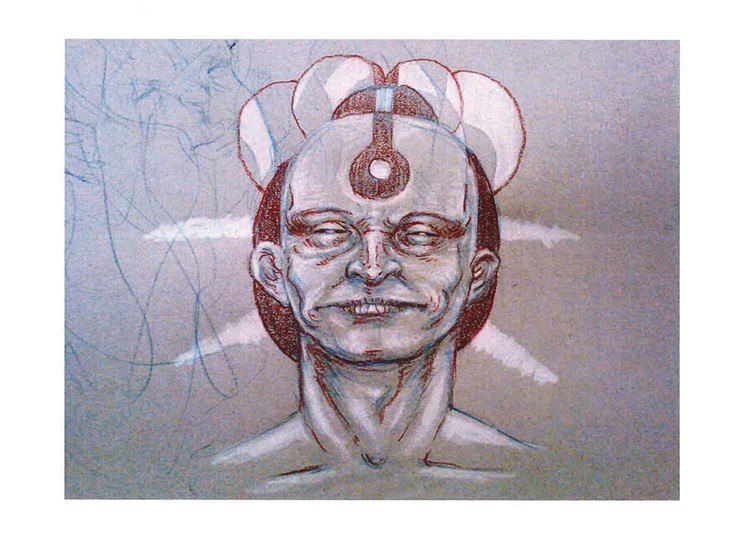

Bessent was born in Louisiana, but grew up with his sister, Michelle, near the shores of Lake Michigan, where they’d stroll along a shoreline covered in smooth gray stones, or explore lush, towering woods. He was tall, with a distinct oblong face and thick head of wavy dark brown hair he’d cut way back, and a epicycle tattoo on the inside of his right forearm. He had lived in Phoenix for nearly two decades, growing into his artistic talent as Roosevelt Row was blossoming into an arts district.

Barbara Wert, Bessent’s mother, recalls him sitting with paper and pencil before reaching his first birthday, and says he liked to surreptitiously draw people’s portraits while engaging them in a game of chess.

Friends recall not only his creative talents, but his authenticity as well. “David had a transcendent kindness,” says James B. Hunt, an artist best known for hiding surrealist artworks downtown under the name NXOEED, then letting the people who find his works keep them.

“David was universally beloved,” Hunt says.

Lina Luna credits both artists with helping her find her bliss. “I decided to pursue a full-time mind/body practice because of conversations with them,” she says.

She’s a student with Southwest Institute of Healing Arts in Tempe, and says Walter often helped by letting her practice various techniques on him. “I performed hypnotherapy on him at Encanto Park that Thursday,” she says of the day before the shooting. “I asked him his intention, and he said he just wanted to be at peace.”

That was the last time she saw him.

A month after the murders, Phoenix police hadn’t identified a suspect, or shared details of the crime with the public. But one careful observer knows more than most, and the details are chilling.

Brighton Casey Brick didn’t witness the murders, but she’s seen surveillance footage from a camera on top of the Embassy Condos, which was posted on Facebook. It’s since been taken down, at the request of law enforcement officials, who declined to show the tape to Phoenix New Times. But the images are seared into Brick’s brain.

Here’s how she describes them, starting with seeing the artists heading west after work.

“They were walking home. Both had their bikes. They had to-go food. David always had art supplies. They were on the south side of the street, crossing the intersection of Third Avenue and Roosevelt, catty-corner from Pita Jungle. There’s a lot behind the wellness center, with a world peace mural.”

Next, Brick describes the vehicle involved with the incident, which the Phoenix Police Department has since confirmed is a late-’90s or early 2000s Dodge Durango.

“You see a white SUV drive west on Roosevelt. It stops in the middle of the road and makes a U-turn, and shines its lights toward the two. It pulls down the alleyway and parks and waits for them. It was very obviously premeditated, like the car hung around for a while waiting for someone.”

With a calm, steady voice that belies the horror of seeing her best friend gunned down, Brick reveals details about the actual shooting.

“They cross the street and walk past the alleyway, then you see two or maybe more shadowy figures approach them, walking closer to David and Zac. Within seconds, one [of the suspects] gets thrown on the floor, and you hear four gunshots. It was so nonsensical and fast.”

Sagasta has vivid memories of getting the news.

“At first the cops thought a customer was involved, because they found a to-go bag in a backpack,” he says. On Friday, Sagasta learned that Walter and Bessent were the victims. Then, he set about breaking the news to his staff. “We took aside the ones we knew would take it the hardest,” he says. “Some broke down, and some had a lot of questions.”

Jobot nixed plans to have artists live-paint in front of the restaurant that night, as word of the shooting began to spread. “I was surprised like most people to hear what happened,” says Greg Esser, a longtime artist, business owner, and downtown advocate who serves as vice president for the Roosevelt Row Community Development Corporation. “I learned about it by word of mouth.”

Sagasta started getting calls from neighbors and businesses, asking how they could help. On Sunday night, October 7, about two dozen people gathered for a candlelight vigil on the sidewalk outside Jobot, leaving flowers and writing tributes in colorful chalk. One chalk drawing featured the victims’ first names, surrounded by a heart with wings.

“We went through that weekend numb,” Sagasta says.

Support for the victims’ families quickly swelled. Memorials and fundraisers ranged from concerts to house parties, held during the month following the murders. Many were done without much fanfare so they wouldn’t attract people outside the victims’ circles of friends. Three people started GoFundMe accounts online, raising a total of more than $15,000 for the artists’ families by early November. Nearby businesses donated goods for a Jobot-organized raffle.

Some tributes were more personal.

Connor Fry turned a green 1-inch binder into a memory book, then set it on top of a small, square table at Jobot so people could write their reflections down for Walter’s family. Then, he set one of Walter’s small paintings beside it. Pablo Luna, a Jobot cook named for his father, a local legend in graffiti art, made a small Día de los Muertos altar honoring both victims.

El Mac posted a portrait of Bessent, adding a comment that included these words that seem to echo the collective heart of an arts community in mourning:

“It is a confusing, harsh cruelty that someone so loved and so notoriously gentle should be victim to such senseless violence.”

Several friends and fellow creatives are looking for ways to help keep memories of the artists, and their contributions to the community, alive. Brick plans to publish a collection of Walter’s poetry, and collaborate on a permanent memorial to both artists at Jobot.

Meanwhile, an artist named Clarke Riedy is looking at the big picture, including the ways artists who build thriving arts districts get priced out of the very areas they’re responsible for creating. It’s a charge that many have leveled against Phoenix in recent years.

“Artists are the absolute lifeblood of this city,” he says. “We need to take care of that which we say we treasure.”

Riedy was an apprentice to famed sculptor John Waddell, an Arizona artist whose bronze works include several female dancers outside the Herberger Theater Center, and the figures of four young black women killed during a 1963 church bombing in Alabama. “One of the greatest things he did for me was provide the space and conditions to do the work and practice,” he recalls.

When Riedy moved to Hawaii in 2012, he left behind a studio located in an industrial area behind Sky Harbor Airport, which went largely unused. So he decided to see whether Bessent, who’d shown exceptional promise while taking his drawing classes years before, might like to use it. That was back in 2015 or 2016, when Bessent was making smaller-scale drawings in sketchbooks, in part because he lacked the space to do anything larger.

He used the studio for two years, creating a new body of work comprising about two dozen large-scale abstract paintings. “I had no idea what he would do,” Riedy says. “His work had been very representational for years, but he was really evolving a new expressionism.”

Turns out, Bessent was murdered before he could unveil the paintings. “He had brought this great effort to a stunning conclusion, and all that was really left was for him to have an art show and get name recognition and take off from there.”

For Riedy, the murders are both a horrible personal tragedy for the artists’ loved ones, and a cautionary tale for a city that isn’t doing enough to assure that the artists who build community hubs like Roosevelt Row aren’t forgotten when developers decide to capitalize on the fruits of those labors. “This city is not looking after its artists and precious cultural resources,” he says.

It’s possible the impact of these artists could be magnified in coming years, as their deaths inspire people to put forward strategies for creating more places where artists can live and work.

“Affordable housing will be crucial to allowing that form of cultural development to go on,” Riedy says. “We have to redevelop the city as affordable rather than looking for affordability on the fringes.”

He’s got some ideas about how to make that happen, inspired in part by artist colonies like Cattle Track in Scottsdale, and the Apache Art Studios that Joel Coplin and Jo-Ann Lowney recently sold to fund a new studio and gallery space called Gallery 119 just east of the Arizona Capitol.

Riedy hopes to present the first exhibition of Bessent’s large-scale paintings at Gallery 119 next spring, but it’s too soon to know whether and how works by Bessent and Walter will get shown on a larger scale.

For now, the focus remains supporting the victims’ families.

Three weeks after Bessent’s death, Barbara Wert headed right into the heart of Roosevelt Row.

It was First Friday in November, where the streets were filled once again with artisans, musicians, and poets. One artist twirled a long rod, shaping newly fired glass. Another stood atop a wooden crate, dressed in circus attire while delivering an ode to magical thinking. Young musicians played electric guitars plugged into amps, competing with street preachers warning of imminent fire and brimstone for the unrepentant.

She stopped for a while at a hair salon called Public Image, where they were showing a couple of her son’s watercolor drawings and a T-shirt with one of his black silhouette-style graphics. Outside, people milled past, crowded onto sidewalks where street vendors offered candied apples, lavender-scented soaps, and hand-pounded metal pendants. Then she headed over to The Lost Leaf, snagging a place at an old-school wooden picnic table on the front lawn, talking with people she knows, and people she’d never met before.

For each person, she had an encouraging word, often delivered with a hug. She even managed to get in a little time on the dance floor while Djentrification mixed music, immersing herself in the world that nurtured her son for so many years. All around her, the room was filled with the pulsing hum of fervent conversations, playful flirtations, and youthful laughter.

She drank it all in, with eyes that smile just like her son’s, revealing that David’s heart is beating stronger than ever in this place.

“People ask me how I can even stand to be here, so close to where my son was shot,” Wert says. She pauses.

“This is his community, his tribe,” she says. “We have to turn hate into love.”

Correction: The original version of this story stated that the video surveillance footage was taken at The Clarendon hotel. The information has been corrected to the Embassy Condos.

Update: The Phoenix Police Department announced on August 21, 2019, that it has arrested two individuals and charged them with the murders of Zachary Walter and David Bessent. Antonio Palafox-Zermeno, age 14 at the time, and Castulo Cervantes, age 15 at the time, are being charged as adults. The investigation is still ongoing and detectives believe there were at least two more suspects involved. Police are asking individuals with information to contact Silent Witness at 480-WITNESS or 480-TESTIGO (Spanish).

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]