Spielberg premieres October 7 on HBO.

While the studios accuse critics and Rotten Tomatoes of killing the movie business, Steven Spielberg is happy to look right into the camera and say that Pauline Kael had his number. “She was right,” says the world’s most profitable director deep into Spielberg, Susan Lacy’s HBO documentary survey of his career. “I hadn’t grown up yet.”

He’s referring to Kael’s New Yorker review of Spielberg’s first full made-for-theaters feature, 1974’s Goldie Hawn-on-the-lam car-mayhem drama The Sugarland Express. Kael lavished the director, then 27, with glittering praise for his compositional sense and facility with actors. “He could be that rarity among directors — a born entertainer,” she wrote, “perhaps a new generation’s Howard Hawks.” But Kael also cut. “If there is such a thing as a movie sense — and I think there is … Spielberg really has it. But he may be so full of it that he doesn’t have much else. There’s no sign of the emergence of a new film artist (such as Martin Scorsese) in The Sugarland Express.”

It may be hard for younger film fans to appreciate now, a few years after Lincoln entered American life as celebrated as a new wing of the Smithsonian, but the question that dogged the first half of Spielberg’s career was “Will he ever grow up?” Even today, in Lacy’s film, many of the people who know him best treat him as something of a kid. “At first, he just scared us,” says a sister, describing the pranks and horror films he would spring on them. “But through his movies he gets to scare the shit out of everyone now.” Brian De Palma notes that, over the years, Spielberg — the most successful of their coterie of ’70s dude-director movie brats – has developed a “mastery.” Francis Ford Coppola is notably cagy, telling Lacy’s cameras, “He was very fortunate that the kind of movie that he had a sense for was the kind of movie that the audience had a sense for.”

In vintage film clips and photos we see these men, and George Lucas, reveling in their promise in ’70s Los Angeles. Lucas — who, less forgiving of critics than Spielberg, would name the villain in 1988’s Willow “Kael” — admits that at first he thought the wunderkind Spielberg was “too Hollywood-y,” not an independent-minded countercultural force like Coppola or himself. But then Lucas stepped out of a party to catch the opening of Duel, the ferociously suspenseful TV movie that Spielberg directed for ABC in 1971, and wound up dazzled for the full two hours. He certainly saw that movie sense, exactly what he’d need a decade later as producer of the Indiana Jones films, but he keeps quiet about whether he saw more.

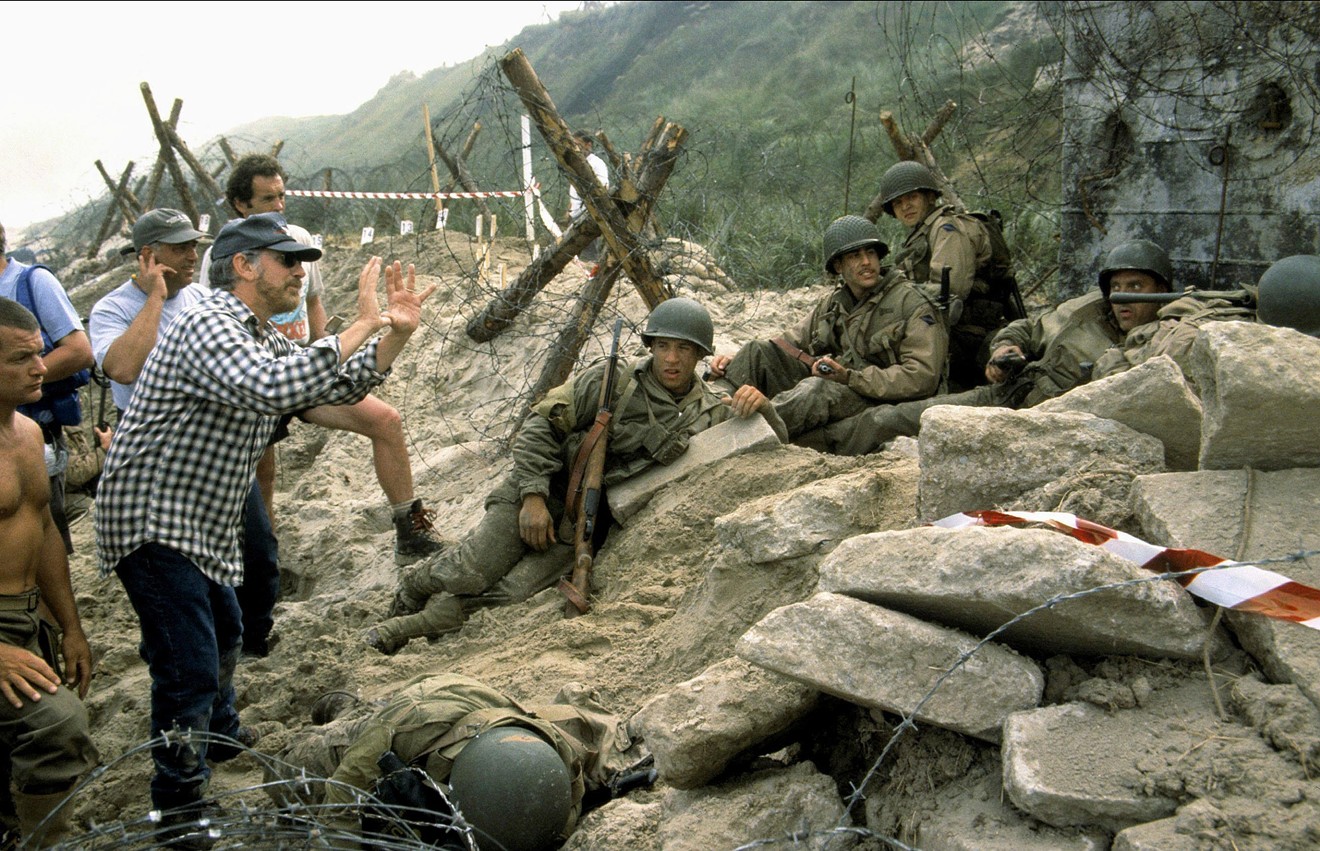

Lucas often gets blamed for that series’ dire fourth entry, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, a movie that Spielberg breezes over. (Also mostly skipped: Hook, Always, The Terminal, The Twilight Zone, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, War Horse, and 2011’s The Adventures of Tintin, the film that gets my vote for the best Raiders of the Lost Ark sequel.) Lacy’s doc offers some insights directly and might nudge you to others. Its narrative of maturation toward mastery, the ripening of Spielberg, suggests, for example, what actually went wrong in the Indy pictures: The dazzlingly childish Spielberg of Raiders (1981) was not the Responsible Global Citizen who made Crystal Skull (2008). In Schindler’s List (1993) and Saving Private Ryan (1998), he applied that movie sense — that zeal and that gift for staging and framing mayhem — to real-world horrors.

In Munich (2005), a key film whose politics gets soundly parsed in Spielberg, and War of the Worlds (also 2005), he interrogates that gift, crafting tense and exciting set piece sequences yet stripping away the heroics. In War of the Worlds, Tom Cruise, as a prickly dad, can’t possibly save the day, so he spends the film running from the aliens to save his family, a perfect inverse of what Richard Dreyfuss’ family-fleeing Roy Neary did in Close Encounters. In Munich, Spielberg worries over the very notion of violent heroism, the lie that more killing is the answer, his own apparent uncertainty that the staging of slaughter is at all edifying. Of course, Indiana Jones couldn’t make the ka-powing of Russian soldiers hilarious fun in 2008 — the born entertainer directing him had lost his stomach for what pleases crowds.

Spielberg’s ambivalence toward his mastery of comic violence stands as one of many topics that Spielberg suggests but doesn’t actually examine. While well over two hours, Lacy’s film zips along, always onto the next thing, tantalizing with behind-the-scenes footage (watch him guide Drew Barrymore and Henry Thomas through tricky E.T. reaction shots) and too-quick character studies. Michael Kahn, who has edited most Spielberg films since Close Encounters, doesn’t get to tell us much about their process, or even to point out the astonishing fact that the man who cut together Private Ryan’s Omaha Beach sequence also edited 130 episodes of Hogan’s Heroes.

Tom Hanks attests to Spielberg’s openness to inspiration on the set, while Liam Neeson crabs about having been made to feel like the director’s “puppet” while filming Schindler’s List. Their anecdotes — both thinly detailed — square with Spielberg’s own insistence that, while on the job, he must always look wholly confident, even though he believes he gets his best ideas when he’s uncertain, when he’s edging toward panic. (Watch Munich again to see what Spielberg is like when he’s feeling for something to say but not quite sure he’s found it.) Hanks speaks of Spielberg with the collegial reverence of a Kennedy Honors speech; Neeson does so with the respectful distaste you might have for a hard boss who was eventually proven right. Only Dustin Hoffman seems to see the Spielberg that Spielberg purports to be hiding. “Steven’s like a guy who works for Steven Spielberg.”

Lacy emphasizes Spielberg’s genius for expressive motion, with moving a camera within a scene, but doesn’t delve deeply into craft. Spielberg instead finds the director acknowledging the ways that his personal life resonate in the work. “Movies are my therapy,” he admits, which is no surprise for anyone who has gone to the movies during the era of his reign. What’s most revealing, here, is his self-awareness, the way that he anticipates and acknowledges what we suspect about him just from viewing the films. For one, he’s happy to admit that he was too “timid” and “embarrassed” to film the crucial scene in The Color Purple where Shug shows Celie her clitoris.

And he acknowledges the autobiographical origins of many of his personal themes. When his parents broke up, Spielberg — just like the young boy in Close Encounters — shouted that his father was a crybaby. “My main religion was suburbia,” Spielberg says, not a surprise from the auteur of E.T. and a collector of Norman Rockwells, but still jarring from the director of Schindler’s List and the founder of the Shoah Foundation. He’s frank, in the film, about his youthful efforts to deny his heritage. When he was growing up in Phoenix, he tells us, neighborhood kids sometimes chanted in his yard, “The Spielbergs are dirty Jews!”

Then there’s the curious story of his parents, whose breakup, when he was young, inspired a host of distant/difficult fathers in his movies. As they did on 60 Minutes in 2012, the parents here gently correct the record, with Spielberg’s endorsement. It’s touching to get the behind-the-scenes truth, but you probably had guessed already that there had been a reconciliation. Just like Indiana Jones, the director has discovered that his old man wasn’t so bad after all. The thing that Spielberg eventually found to put into his work, besides that still-thrilling movie sense, is himself.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]