I have a recurring nightmare. It isn’t always the same, but it always involves a last-minute, present-day reopening of Hollywood Records and Tapes, the record store I managed decades ago. Until one day when it was abruptly shuttered by the building owners following a bank foreclosure. In my dream, I’m freaking out — rushing around, un-boxing 8-tracks, installing LP racks, and trying to remember how to fill out an Ennis form. Because customers are coming any minute now and we’ve been closed for 32 years!

Ancient history. But memories of losing “my” music shop came flooding back when I heard that the Roosevelt Row home of Revolver Records is for sale. Wide awake, that news brought a flood of my own long-ago panic when one day my record store was no longer there.

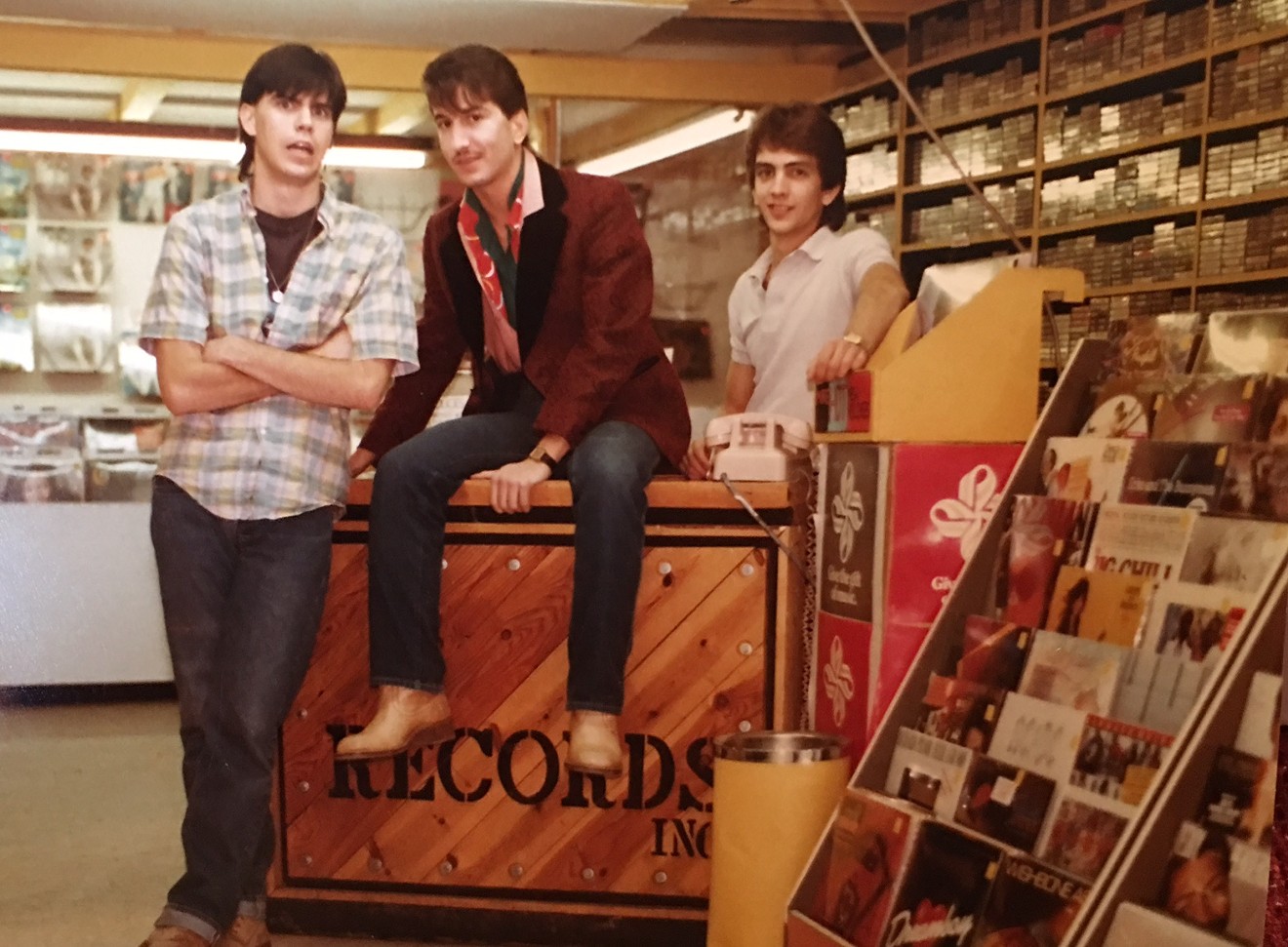

Neither the store nor the foreclosure was mine. The Hollywood Records and Tapes chain was owned by a local album distribution company called Associated Distributors. They sold albums, singles, 8-tracks, and cassettes; CDs hadn’t been invented yet when I worked there in the early and mid-1980s. Associated’s big clients were Motown and Arista, back when those labels were independents. The Associated folks believed in the whole pride-of-ownership approach to management, so they referred to their 11 Hollywood stores as “ours.” As in, “Your store isn’t selling enough Dazz Band.” Or “Angela Bofill could be doing better for you.” They left me alone to run my store however I, a record fanatic barely out of my teens, wanted. And what I wanted was a shop that catered to everyone in the neighborhood.

When I got there, the Camelback store was catering mostly to heavy metal dudes. The walls and ceiling were painted black; the windows were covered in promo posters for Iron Maiden and KISS and a new band called Twisted Sister. We couldn’t compete with the just-opened Tower Records store up the road at ChrisTown, which was eating us alive in the new-release game. Tower’s record label co-op ad dollars allowed them to sell the new REO Speedwagon for five bucks, while I had to sell it at just below list price. They had 13,000 square feet and a staff of 20 sneering cool kids running their registers. I was working out of 500 square feet of renovated 1940s tract home, with a staff of two.

I decided to turn our shop into a neighborhood record store, one where you could special-order a Dolly Parton record from six years ago without having to endure the smirks of a smart-ass clerk. Where you could go on payday because you wanted to invest in some new music, and the guy behind the counter wouldn’t try to sell you what he thought was cool, but rather music you might like but didn’t know about.

I painted the store white, got rid of the Metallica posters, and instigated a special order policy: If you wanted it and we didn’t have it in stock, I’d head down to the giant Associated warehouse every Monday in search of it. Tower couldn’t do that.

We made a lot of friends. Middle-aged housewives from the hood who liked Janie Fricke and wanted to know “who else was like her” stopped by to listen to my Jennifer Warnes records, and sometimes to buy one. Some of the metal heads still came around, and I convinced a couple of them to buy the head-banging Teresa Straley album on Alfa, a boutique label Associated was distributing. There was the leggy blonde putting herself through law school by dancing at a titty bar; I played disco singles for her for about an hour every Friday morning. And the 11-year-old boy who lived around the corner and was obsessed with Diana Ross and the Supremes. None of his classmates would talk to him about Cindy Birdsong, so he hung around and talked to me while I inventoried Folkways albums and alphabetized cassingles.

For music fans and vinyl junkies, a neighborhood record store is a luxury. I knew that because I’d grown up with one — also a Hollywood Records and Tapes store, the one behind my childhood home. There, I could hang on the counter for hours, listening to new music and talking to clerks who cared about things like whether Lou Reed should have left RCA to sign with an indie. Guys who wanted me to hear the new album by this little-known folkie, Cris Williamson, or who saved for me the promo-only sampler of new tunes by The Plastics, a Japanese band that sang in English, phonetically. I bought them all — Lou Reed’s Growing Up in Public, Cris Williamson’s Stranger in Paradise, the Plastics LP. I still have them; I still play them from time to time.

I was reminded recently of how important a neighborhood record shop can be. A couple weeks ago, I pulled out my Bruce Roberts records and, while playing his second album, discovered a distinct snap-crackle-pop on Side One. I could have grabbed my iPhone and bought a replacement on eBay, but I didn’t have to. Instead I climbed into my car and drove the half-mile to Revolver, where I bought two copies of this 1980 LP — one for the pristine vinyl; the other because it was a white-label promo that I didn’t already have. The pair set me back all of four bucks, and I was back home and playing “Cool Fool” within a half-hour. Better yet, the guy who rang me up didn’t make a face and ask who the hell Bruce Roberts was.

The guys at Revolver are like that. When my husband and I lingered over the Glen Campbell albums late one recent night, the clerk came over to tell us to take our time, he’d stay open till we’d found what we wanted. While he rang up our purchase, he asked questions about Glen Campbell songs and wondered if we ever listened to Jimmy Webb records. I wanted to tell him about Hollywood Records and the kid who loved the Supremes, but it was past closing time.

The Revolver building on Roosevelt is locally owned by a partnership called Central City Ventures, which owns a big hunk of Roosevelt Row, including the spaces now occupied by The Nash and Short Leash Hotdogs. When Colorado-based Baron Properties bought up two corners of Roosevelt Row a couple years ago, it knocked down the building that housed GreenHaus, the beloved artspace boutique, and put up a multi-level apartment building. Last year, Chandler-based Desert Viking bought still more Roosevelt Row properties for The Blocks on Roosevelt Row, an adaptive reuse project that booted Five 15 Arts and Lotus Contemporary Arts from their downtown homes.

It’s likely that the Roosevelt Street building Revolver is leasing will go the way of the wrecking ball, once it’s sold. I’ve read about how, if that happens, Revolver owner T.J. Jordan will relocate the Roosevelt inventory to his other store in Arcadia, and perhaps find a new location for the RoRo shop.

I hope his neighborhood customers follow him, wherever he goes. But more than that, I hope T.J. doesn’t start having record-store nightmares.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]