The thieves approached the house under the cover of darkness, sneaking behind the two-bedroom dwelling in Chandler rented by Arizona State University student Zachary Rowe.

Rowe, 25, was a pre-law major in his final year as an undergrad. He lived alone with his dog, Chloe, and apparently was watching TV on a December night in 2008 when Chloe sensed that intruders were nearing the house's rear entrance. She moved toward it, barking.

Alarmed, Rowe grabbed the .40-caliber Glock he always kept nearby, one of a handful of weapons later found in the house. He fired twice at the men, either returning fire or firing first.

One of the thieves also was armed with a handgun and shot twice at Rowe.

According to an autopsy performed by the Maricopa County Office of the Medical Examiner, one of the bullets passed across the top of Rowe's scalp, grazing the top of the brain and lodging in the skull.

The other bullet cut a more deadly path, entering from the back of the head and exiting from the left temple. This probably was the kill shot, whether it came first or second.

The thieves had come looking for drugs and money. Rowe dealt marijuana, heroin, pills. It was a classic drug rip gone awry. Now the two men were faced with the possibility of a murder-one rap.

They left the house but later returned with gasoline, dumping it on Rowe's body and around the room, igniting it with a pack of matches in an attempt to burn down the house and leave no evidence of their crime.

The heat was so intense that it melted the plastic on Rowe's handguns and on many of the syringes that littered one table.

Some of the glass containers holding marijuana were blackened, but much of the pot, some of it ready for sale, survived, as did other illicit substances.

Live rounds of ammunition were ignited by the blaze, and the resulting firecracker-like pops alerted neighbors, who called 911.

After the firefighters finished their work, Chandler cops surveyed the scene, finding a burned-out living room, with Rowe's blackened corpse on the floor and the partially melted Glock nearby.

Chloe's carcass was discovered in another part of the house, the pet having succumbed to the fire.

Friends and acquaintances advised police that Rowe was a "middle fish" in the drug-dealing world. He sold "high-grade marijuana" and other substances and may have dealt in stolen merchandise. He was both secretive and paranoid, making friends call ahead of time before coming over.

Newspaper accounts spoke of Rowe's double life, his aspirations to attend law school, and his well-educated parents: His dad was a professor of computer science at ASU, and his mom a special-ed instructor with an advanced degree.

But the case went cold until 2012, when ex-con Gabe Golden, who lived across from Rowe, fingered two ne'er-do-wells who ran in his circle: Rory Gene Coriell and William Hayden Crawford.

Last year, Crawford and Coriell were arrested and indicted for first-degree murder, arson, and attempted robbery. Coriell quickly copped a plea deal for manslaughter in return for his willingness to testify against Crawford, pinning the murder on his ex-friend.

Crawford claimed he was innocent, but where have we heard that before? He had been in and out of trouble since he was a kid, had a history of drug abuse, and had two previous felony convictions, for aggravated assault and possession of cocaine with intent to sell.

He'd done hard time in the Arizona Department of Corrections. Now, two ex-friends had rolled on him, and he faced 25 years to life on the murder count alone.

So Crawford turned to a defense lawyer with a reputation for representing the wretched, the wicked, and the irredeemable, who repeatedly had stolen victory -- or as close to it as possible -- from the maw of defeat: Phoenix attorney Richard Gaxiola.

Despised by prosecutors and cops, hero to Hells Angels, confidant of drug dealers, fraudsters, killers, and freaks, Gaxiola is somewhat like fictional Los Angeles lawyer Mickey Haller, portrayed by Matthew McConaughey in the screen adaptation of the Michael Connelly novel The Lincoln Lawyer.

Albeit without the Lincoln Town Car or the chauffeur.

Gaxiola, or "Gax," as some call him, doesn't run TV ads in the vein of likable shyster Saul Goodman on Breaking Bad. You won't see his face on the side of a bus or beaming from an electronic billboard over Interstate 10 in Phoenix, like those of other legal beagles in town.

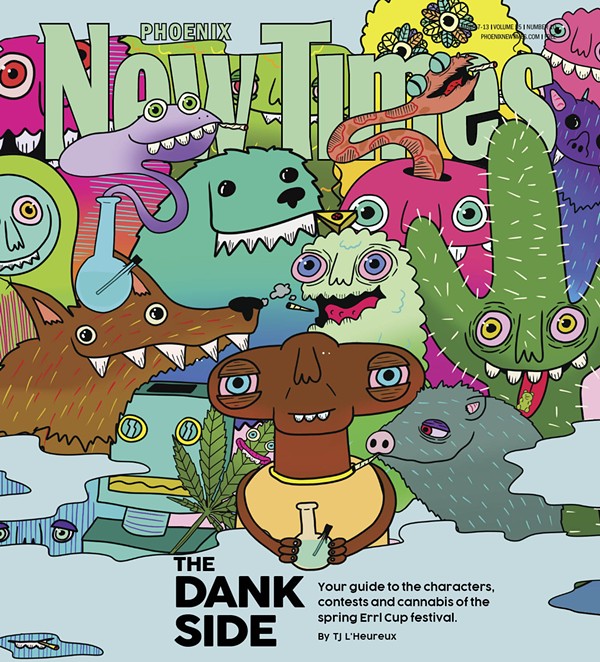

But if you're up on murder one, just finished dodging bullets in a biker shootout, or were popped selling chocolate bars laced with THC, well, Gax is your man.

Clark Kent in black horn rims. That's what Hayden Crawford (no one calls him by his first name, William) looks like as he stands in bumblebee stripes behind a thick plastic window in Sheriff Joe Arpaio's notorious Fourth Avenue Jail and talks about his upcoming sentencing hearing, scheduled for May 15 before Superior Court Judge Bruce Cohen.

Pale and serious, Crawford, 28, has been held on a $1 million bond since his arrest in January 2014 for arson, attempted robbery, and the home-invasion murder of Zachary Rowe.

But after an intense 13-month investigation by Gaxiola that involved interviewing and deposing 20 to 30 witnesses, the state's theory of the case has been ripped to shreds, and Crawford, who was ratted out by fellow criminals Gabe Golden and Rory Coriell in the Rowe murder, no longer is on the hot seat.

In February, Crawford entered into an agreement with the Maricopa County Attorney's Office, in which he pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit armed robbery, for which he could be sentenced to three to 12 1/2 years in prison.

He and Gaxiola hope for the low end, obviously. In any case, it's a damn sight better than 25 to life for a murder that the County Attorney's Office now admits Crawford didn't do.

Thing is, Crawford concedes that he'd agreed to participate in the robbery, which he says was planned by Golden and Coriell.

But he claims he chose not to go along with Golden and Coriell that night.

"I just didn't want to steal anything," he tells New Times.

He also says he wanted to break with Golden but that he feared him and therefore lied, telling Golden he would participate, though he wanted no such thing.

Crawford says he is remorseful, and he believes he deserves some time in prison, even if he wasn't with Golden and Coriell the night Rowe was murdered.

"I knew about this crime and didn't come forward," he admits.

Still, he balks at the notion that he should do decades in prison for what he calls "the contemplation of a crime." Three years would be plenty, he says.

Currently, Golden, 38, is doing four years in prison for misconduct involving weapons.

Previously, he's done time for narcotics, burglary, and aggravated assault.

He hasn't been indicted on charges related to Rowe's murder. In fact, he was, until recently, going to be the state's star witness at Crawford's murder trial.

But now that the murder charge has been tossed, the County Attorney's Office has promised, as part of the plea agreement, not to bring any more charges against Crawford in the Rowe killing.

At a court-ordered deposition arranged by Gaxiola last year, Golden invoked his right against self-incrimination, as enshrined in the Fifth Amendment.

Nor is Golden still willing to testify against Crawford, which is ironic because it was Golden who offered up Crawford and Coriell to Chandler police in 2012, shortly after he was arrested on theft and burglary charges.

Back then, Golden was eager to give Chandler cops something they wanted to save himself. According to one police memo, Golden told Detective Beth Hill:

"What can I do to get me out of trouble? What about a murder thing? Like I have a lot of information on a murder. It happened in Chandler. I need something in writing to clear me if I give you info. [The killers] said they didn't think [the victim] was home, and the guy was there and got [rounds shot] at him . . . They went back and . . . dumped gas in his mouth, burned down the house."

The tale Golden told Hill and Chandler Detective Cassandra Cocking, the case agent, eventually would become the state's theory about how and why the arson and murder took place.

Golden had intimate knowledge of how the crime went down because, he later would suggest to detectives, the killers had told him everything about the murder and arson, which just happened to occur at a house directly across from his.

Golden told Hill that it was a "burglary gone bad," as Hill wrote in her memo:

"[The killers] were told by another individual who bought [drugs] from the victim, [that Rowe] had a lot of drugs, property and over $100K in cash at his house. When they arrived at the victim's house and entered the backyard, they peeked through a back window and saw a reflection of the television screen and realized someone was at the residence. [The victim's] dog jumped at the Arcadia door and alerted the victim. Victim grabbed gun and approached Arcadia door, went out back, and shot at suspects. One of the suspects got shot on the cheek . . . The suspects returned gunfire."

As Gaxiola pointed out in various court filings, after three recorded interviews in 2012 with two different Chandler detectives, Golden finally coughed up the name of the person he said was the shooter: Rory Coriell, 30.

During a fourth interview, in May 2013, Detective Cocking brought up one of Coriell's associates: Hayden Crawford. Golden's response, perhaps in hindsight, was predictable.

In one account of the interview, Cocking wrote:

"I also indicated [to Golden] that I had spoken with Hayden [Crawford], one of Rory [Coriell's] friends. Golden indicated he thinks [Crawford] was the one with Rory that night [of the murder]."

Golden also gave up the name of the person who supposedly told the killers about the drugs and loot to be found at Rowe's residence, another of Golden's flunkies, Eric Kush, a.k.a. Keebler.

But, according to Gaxiola, Golden's knowledge of the crime scene was too accurate for someone supposedly not present during the killing.

"There were specific details of the configuration of the house, the backyard, the location, [and the crime itself]," Gaxiola says at his office near Thomas and Central.

"[Golden] had to have personal knowledge to actively convey these details to [the police]," the lawyer says. "And his attempt to distance himself from the crime was bought hook, line, and sinker by law enforcement."

What about Coriell and his willingness to testify after copping a plea deal?

"Certainly, the other co-defendant, Coriell, can't claim anything other than he was involved in the crime because he pleaded guilty to manslaughter," Gaxiola says.

Coriell also had another reason to rat out his ex-buddy, Gaxiola claims: to save his own hide from murder one.

Golden was another story altogether.

Through reams of transcripts, the attorney painted a damning portrait of Golden as a violent yet charismatic individual who could cajole and sometimes threaten his friends into performing burglaries with him. His two favorite targets were johns and drug dealers.

People in Golden's criminal clique admitted that they were frightened of the muscular manipulator, who, according to the Department of Corrections website, is 6 feet tall and weighs a bruising 265 pounds.

For instance, during a deposition, Bryson Higley described a 20-year friendship with Golden, whom he once considered like a brother.

Higley, who admitted to doing robberies with Golden, said he was willing to talk about Golden because he no longer feared repercussions, given that Golden was off the streets.

Higley said Golden typically would find out where one of his friends scored drugs and then rob the dealer, sometimes immobilizing him with Mace.

"It was kind of a running joke how long a can of Mace would last," Higley testified about Golden's purchase of a new can from a Bass Pro Shop.

Golden also would do something he called "cash and bashing" by driving around prostitutes and robbing their johns.

Once an escort secured a john's cash, Golden would be signaled via Bluetooth, kick in the door, and Mace the john.

"That was basically what [Golden] did for a living for the last couple of years I hung out with him," Higley stated under oath.

Golden regularly would beat up his "friends" and coerce them into committing crimes for him, Higley said.

Similarly, Kush, Golden's star patsy, admitted in a deposition to getting assaulted and ripped off by the bully to the tune of $11,000.

Golden once got him to commit credit fraud by smacking him around, Kush said.

Kush's testimony paralleled Higley's when it came to Golden's robbing johns and drug dealers.

Also, Kush copped to purchasing drugs from Rowe, with whom he was close.

Eventually, Kush said, he told Golden that Rowe dealt drugs across the street from him.

From that point on, Golden expressed a desire to rob Rowe.

Kush said he introduced them to each other, taking Golden to Rowe's house, where they smoked pot together.

Kush further confirmed that after the fire at Rowe's house, Coriell had a fresh scar under his eye, like the one Golden described to Chandler detectives.

Everything that Kush knew about the crime came from Golden, Kush told Gaxiola.

Kush believed Golden was involved in the home invasion and suspected that Coriell and Crawford were involved, too. But he claimed no direct knowledge of what went down with Rowe's murder.

At one point, Gaxiola asked Kush whether he believed, considering Golden's history and his violent tendencies, that taking Golden to Rowe's house was "problematic."

"In hindsight," Kush replied, "yes."

During depositions in the case, the hits just kept coming, pointing responsibility for the killing away from Crawford and toward Golden.

In his deposition, Higley told Gaxiola that during a trip he and Golden made to California in 2009, Golden admitted to involvement in Rowe's murder with an unnamed person, whom Higley presumed was Coriell.

An emotional Golden put the blame on his accomplice, according to Higley.

"So they went to go do this [robbery]," Higley testified, paraphrasing Golden. "[Golden] said they went in the backyard or they got into the house . . . everything should have been fine, and then this idiot ran up and just shot the dude for no reason."

After the fire at Rowe's house, Higley said, he heard others in their circle say, "[Golden] is going to set [Coriell] up for this murder."

He also recounted how Golden regularly would try to get his friends to take the blame for his crimes.

Higley said Golden did this to him more than once and that Golden spoke vaguely of needing a fall guy for the latest catastrophe.

More damning still are the depositions of two men who said they overheard Golden and Crawford arguing during a confrontation at the Fourth Avenue Jail.

Inmates Benjamin Rosenblum and Christopher Welch described under oath to Gaxiola how they heard Crawford call out Golden, in a cell next to him, as a snitch.

Welch recalled Golden's denying being a snitch and Crawford's saying that was "B.S." because Golden's name was in court paperwork dealing with Crawford's case.

"Then," remembered Welch, "I heard Gabe say, 'Well, I don't know why they got you in here on that murder charge when you didn't have nothing to do with it.'"

Rosenblum had a similar memory of the argument, with Golden denying that he'd squealed on Crawford: "[Golden] said he's not telling on [Crawford] for something he never did."

Despite such gems, it's difficult to do justice to the amount of work Gaxiola put into the case, locating witnesses with the assistance of private detective Michael Branham and forcing the recalcitrant to testify via court order.

Gaxiola interviewed witnesses at halfway houses and in prison. In some cases, the witnesses switched their stories from what they previously had told Chandler cops.

"We collected enough evidence to not only eradicate the murder and arson charge against Crawford," Gaxiola says, "but also to serve up Golden on a silver platter to the state, whom they refuse to indict."

Indeed, the fallout from the case continues, even as this story goes to press.

Recently, Superior Court Judge Karen Mullins rejected Rory Coriell's plea deal of manslaughter as "not being in the interest of justice."

Mullins didn't get more specific in her minute entry, but it can be surmised that what Gaxiola has achieved in Crawford's case is spilling over to Coriell's case, influencing its outcome.

It should be noted that in letters to the court, Rowe's family still blames Crawford and Coriell for the killing, despite evidence showing Golden's alleged involvement.

Gaxiola blames this on police and the media, both of which suggested in 2012 that the cold case from 2008 had been solved.

From the Fourth Avenue Jail, Crawford expressed his gratitude for Gaxiola's getting him the conspiracy count, instead of a more serious charge.

Sure, Gaxiola got paid for the work he did: a flat fee up front that would make a nice year's salary for an upper-middle-class American. But it's clear that it's about more than money to Gaxiola. He enjoys digging into meaty cases, going up against the power of the state, and beating prosecutors at their own game.

"Most of the cases in the system are bullshit," he says over lunch at Seamus McCaffrey's in downtown Phoenix. "You just want to level the playing field, just a little bit."

And it's that fight that makes his work so satisfying.

"To me, it's analogous to being on the front lines," he says. "You're right there, defending the Constitution and the constitutional rights of the defendant, your client."

But Gaxiola is self-aware enough to realize that the general public often regards defense attorneys, who protect society's outlaws and outcasts, as shady.

This may be inevitable, given the crimes his clients sometimes are accused of.

In 2012, he represented Todd Alan James, an alleged member of what the Prescott Daily Courier referred to as the "Zonka syndicate," after a potent, THC-laced chocolate bar that authorities claimed was sold illegally at unlicensed marijuana "compassion clubs" in Yavapai and Maricopa counties.

James was looking at such high-level felonies as running a criminal syndicate and transporting narcotics for sale.

Fortunately for James, Gaxiola got the charges knocked down to one count of misdemeanor possession and James received two years of probation.

Also in 2012, Mesa police busted an East Valley towing company, alleging it illegally had towed parked cars and held them for ransom from their owners.

Several individuals, including Gaxiola client Thomas O'Brien, were hit with felony counts involving fraud, operating a criminal enterprise, and theft.

Gaxiola scored his client a deal, allowing him to plead guilty to one class-six felony, called an "open," meaning that if a defendant successfully completes probation, a felony turns into a misdemeanor.

In 2009, Buckeye high school teacher Vincent Petti faced obscenity charges -- and the possibility of being labeled a sex offender for life -- when he was accused of showing cell-phone photos of his penis to female students.

But Petti employed Gaxiola, who looked for errors in the grand jury's indictment.

Gaxiola accused Buckeye cops of not presenting potentially exculpatory evidence to the grand jury. It seems police never were able to find the damning photos on Petti's phone.

Result: Case dismissed.

There's a scene in The Lincoln Lawyer in which a police detective confronts McConaughey's character as the attorney makes his way to court.

"How does someone like you sleep at night with all the scum you represent?" the cop asks.

Gaxiola is used to such questions. He knows that many so-called upstanding citizens turn up their noses at the folks he represents.

But counsels for the defense are a different breed.

"The thing that sets defense attorneys apart is that we don't judge," he explains in the dim light of Seamus McCaffrey's. "We acknowledge the inequities in our system of justice and in life, in general. We have a broader perspective on what's important."

And there's also the reality that today's scumbag could turn out to be tomorrow's good guy.

Take the case of mixed martial artist Benny Madrid, a lightweight champ. In addition to his MMA career, Madrid is a successful coach in Scottsdale and a father of two whose nonprofit organization Dream Big challenges at-risk youth to choose a path out of poverty and crime.

But about a decade ago, Madrid says, he was a big-time drug dealer in South Phoenix, where he grew up.

"I was in a pretty bad business, making millions," Madrid says.

Madrid had used Gaxiola's services in the past for some scrapes with the law, but he really needed his help when Phoenix police busted him with 1,000 pounds of pot.

Charged with class-two felony possession of drugs for sale, Madrid was looking at six to 10 years in prison.

"Rich got me off with probation," Madrid says.

About that same time, Madrid's nephew took a bullet meant for his uncle. Stricken with grief, Madrid resolved to change his life.

Madrid had been a wrestler in high school. He sought out a facility that taught MMA, got his ass beat a few times, and kept coming back for more. He realizes his previous life was a dead end and now accepts the joy of day-to-day existence.

"Rich is a bad dude," Madrid says. "He worked hard for me. I told him I owe him six years of my life."

Now, Gaxiola trains daily in MMA classes taught by Madrid, and the two are friends. Is Gaxiola a good fighter?

"No, no, no," chuckles Madrid. "But, you know, he's learning . . . He had two left feet, two left punches [when he began]. He's dedicated. He has heart."

Gaxiola was born in California but grew up in the small town of Morenci, in Greenlee County, Arizona, where his dad worked in the copper mine as a repairman.

"Growing up was great," he says. "It was out in the country. I thought it was a great upbringing in terms of just being outdoors."

But it also was an upbringing marked by violence and lessons in social justice (or the lack thereof) that inspired him to seek a career as a lawyer and, specifically, as a defense attorney.

The formative experience of Gaxiola's life was the Arizona copper strike of 1983. During an era of union-busting, workers in Morenci, Clifton, and other copper towns went on strike against mining giant Phelps Dodge.

When the company moved to replace the striking miners, violence ensued. Governor Bruce Babbitt sent in the National Guard and patrolmen from the Arizona Department of Public Safety to restore order and break the strike.

Gaxiola said a DPS officer in full riot gear cracked the skull of one of his father's co-workers. Strikers and others were detained for hours and taken to a baseball field, where they were "hosed down like animals," Gaxiola remembers.

His father was one of the miners alleging civil rights violations in federal court, and Gaxiola traveled to Tucson with him to watch them plead their case.

"I was watching this all take place in federal court in Tucson, where my dad was one of the litigants," Gaxiola says. "I got up a fascination with the court process then."

The law offered an alternative to setting cars ablaze and fighting in the streets of Morenci and Clifton with Molotov cocktails and guns, which is what some were doing at the time.

"I think I was always on the underdog's side, as long as I could remember," Gaxiola says. "And witnessing [civil rights litigation] in a federal court, it gives you some sense that there is a remedy to address these kind of things, rather than violence."

Former Arizona State Bar president Ernest Calderon is a friend of Gaxiola's and also hails from Morenci. He believes that coming from the town, one of the oldest in Arizona, helped shape Gaxiola as a lawyer.

"In Morenci, we were the have-nots," says Calderon, who practices corporate and labor law. "His family, my family, we were the working guys, not the copper-company executives. And when you're on the outside looking in -- as we were -- I think that you're always looking to make sure everyone has just treatment."

Not to mention that when you come of age in a town divided by union stalwarts on one side and scabs and strikebreaking cops on the other, weakness is not an option.

"To grow up in Morenci, you have to be tougher than a two-dollar steak," Calderon jokes. "That's one thing I'll say for my colleagues from Morenci: We're advocates. Sometimes you have to take some unpleasant cases and be more assertive than you'd like."

Gaxiola was a good student. He graduated with a degree in political science from the University of Arizona. After college, he briefly taught high school kids in the Tucson Unified School District. He quickly realized teaching wasn't for him and went back to U of A, where he earned a law degree in 2000.

Following law school, he clerked with renowned Tucson attorney and philanthropist Tom Chandler, whom Gaxiola reveres, keeping a photo and a letter from his former employer framed in his office.

"I would not be an attorney were it not for Tom," Gaxiola says of his mentor, who died in December 2013 at age 94.

"He made me learn the art of writing and the art of looking at life from a different perspective -- not so much with a chip on your shoulder."

Gaxiola's first real job as an attorney was with the Maricopa County Public Defender's Office. That's where he cut his teeth as a defense counsel, working long hours during the week and on weekends.

After 22 months of going to trial nonstop, he became burned out and left the Public Defender's Office. Eventually, he landed a job with Phoenix attorney Andrew Alex, where he spent 10 years doing catastrophic personal-injury cases while still specializing in major felony defense.

In 2009, Gaxiola and Alex made headlines when they crossed then-County Attorney Andrew Thomas, arguing that Thomas should be disqualified from certain cases involving judges that Thomas had targeted. Thomas had ginned up criminal charges against the judges and had attempted a RICO suit against them.

A special master was appointed by the court to determine whether the County Attorney's Office should be disqualified in the cases in question. Thomas made the process moot when he launched a failed bid for state attorney general, resigning as county attorney to do so.

Thomas was disbarred in 2012, and Gaxiola still relishes having been one of the few attorneys early on to stand up to the tyrant.

But a client Gaxiola encountered a few years earlier, in 2004, put him in good stead with America's most infamous biker club, the Hells Angels.

The client was Robert "Chico" Mora, a biker whose infamy is such that both the hardest Hells Angels and the most cynical cops brag about encounters with him, no matter how brief.

Once president of the legendary Dirty Dozen motorcycle club's Tucson chapter, Mora was known for taking the rap for his biker brothers for two killings that occurred in a clubhouse shootout and for becoming a boxing champ in prison. He ultimately was instrumental in many members of the Dirty Dozen's "patching over" to the Hells Angels.

Held on a drug charge, Mora summoned Gaxiola to meet him in jail after sending a girlfriend to check out the lawyer.

"He was a menacing figure," Gaxiola says of Mora, who died at age 58 on January 1, 2014.

"I didn't know anything about him when I met him, but here was this large-ass man with these piercing eyes," Gaxiola says. "I had to look away at one time. I'll never forget that because he's one of the only people who's ever done that, even though he was behind bars."

Nor would Gaxiola forget what Mora told him after the stare-down: "He said, 'I'm going to hire you. But don't fuck me. Don't ever fuck me.'"

It was the beginning of a lucrative friendship.

Gaxiola defended Mora more than once on "bullshit drug charges," part of what Gaxiola calls a concerted effort by state and federal law enforcement to harass Mora.

Meanwhile, Gaxiola began researching Mora's life and criminal record, realizing that his new pal was a part of Arizona history.

"There was a time when Mora and the Dirty Dozen pushed back every encroaching biker group in Arizona," Gaxiola says. "And they did it with extreme violence."

Mora's hard-partying lifestyle began to catch up with him during the latter part of the decade during which Gaxiola represented him.

Gaxiola remembers visiting Mora in the hospital once. Two DPS gang task force officers were present as Mora lay in bed, his mountainous frame ill-covered by a too-short hospital gown.

"I remember when he saw me, he got up and bent over to get what looked like a plastic pitcher," Gaxiola says. "Then he starts taking a leak in front of these two cops. Well, they left, and we had a pretty good laugh over that."

In failing health, Mora allowed Gaxiola and a local writer to audiotape the legend for a possible book that never worked out.

Gaxiola then approached Arizona historian Jack August to interest him in the project. August met with Gaxiola and Mora a few times at Durant's, suggesting that Gaxiola approach an L.A. production studio where August had a connection.

The company agreed to help sell the rights to Mora's life story. A script that draws heavily on Mora's days as a Dirty Dozen road warrior has been making the rounds.

Meanwhile, Gaxiola continues to have Hells Angels as repeat clients, the skids having been greased long before by Mora's good words.

Gaxiola estimates that he's represented the Angels in 10 to 15 cases so far.

In the biggest, he represented member Mike Koepke, involved a 2010 shootout between the Hells Angels and a rival bike club, the Vagos, in Chino Valley, north of Prescott.

The two groups exchanged as many as 60 rounds of ammunition, shooting motorcycles and a home where the Angels had been visiting a member who recently had completed probation and was ready to party.

Koepke tells New Times that he first came into contact with Gaxiola through Chico Mora and that Gaxiola had repped him for some minor offenses. So when the Vagos and the Angels shot it out, Gaxiola was his first call.

"Bullets were pretty much still hitting the house while I was on the phone with him," says Koepke, who since has left the club.

According to court filings in the case, the DPS and the statewide Gang and Immigration Intelligence Team Enforcement Mission assigned blame for the shootout to an initial run-in between a prospect for the Vagos gang and some Angels members at a Circle K.

"There was no confrontation," Koepke says. "People [in the store's security video footage] don't even look at each other."

The footage appeared to confirm Koepke's claim.

DPS reports showed that the Vagos prospect called gang members and complained that words had been exchanged between the two sides.

The prospect claimed that the Angels member had tried to start a fight with him.

Following the shootout, in which one Hells Angel was wounded, Koepke and several other Angels members were blamed as the aggressors and hit with multiple charges related to the altercation: attempted murder, aggravated assault threatening and intimidating, disorderly conduct, and misconduct involving weapons, all with gang-enhancement allegations.

"[Koepke] was facing, if convicted, a decades-long sentence," Gaxiola says.

Taking the lead on a team of attorneys, Gaxiola got the case remanded back to the grand jury. But the Yavapai County Attorney secured a second indictment of seven Hells Angels members, with the Vagos members escaping all charges.

A second remand request from Gaxiola was rejected, but it later was learned that the Vagos prospect actually was a paid informant for Gang and Immigration Intelligence Team Enforcement Mission.

Also, the prospect had a beef with the Hells Angels, whom he'd attempted to infiltrate, only to be rebuffed.

The prosecutors and cops were aware of these facts but did not disclose them to the defense.

Gaxiola moved for dismissal of all charges against Koepke and the others, and he got it.

The case made him a hero to Angels members nationwide, and he began receiving calls from California, Nevada, and other states from club bikers seeking legal advice.

At the Buffalo Chip Saloon in Cave Creek, where Hells Angels members were partying during Arizona Bike Week in late March, Cave Creek charter president Bob Eberhardt (a.k.a. Spa Bob), a huge man who recently lost his son Patrick to still-unexplained gunfire on Bell Road in Phoenix, was full of praise for Gaxiola.

"There are lawyers who don't even want to deal with H.A.," Eberhardt says. "So when you find someone like Rich that you can trust and will take your calls at night, [you] don't take that lightly."

Prosecutors and cops, however, call Gaxiola a "club lawyer" and claim he's up to no good.

"What the hell is a club lawyer?" wonders Gaxiola. "To be clear, I represent individuals who happen to be members of the H.A. motorcycle club."

Hey, what does Gaxiola expect from sworn enemies?

Plus, he receives enough praise from the likes of Koepke.

"If Rich takes your case," the ex-biker declares, "he's going to get you off!"

Or, to paraphrase the fictional Saul Goodman, if you're up against the law, "Better ask Gax."

E-mail [email protected].