“There’s no reason we wouldn’t use it exclusively,” said Thoeny, the head brewer at Wren House, in an interview last week at the popular Phoenix microbrewery. “By the time it gets to us, it’s ultra-pure.”

Two years ago, Wren House joined a statewide competition to brew with recycled water. The beer, a hazy IPA called Hydrologic, proved immensely popular, fulfilling its purpose in lifting the profile of reused water.

Thoeny expects to join a second competition in November, this one in Scottsdale during its annual Canal Convergence festival. The only thing he needs to add to the recycled water is minerals — mostly calcium — in order to get the right water profile for brewing, he said.

As Thoeny reflected, another Wren House brewer, Luke Wortendyke, hovered over the bar, testing beer for dissolved oxygen, while sales manager Allister Duker sat at a nearby table, tapping at a laptop. Other humans circulated in and out of the house as Pancho, Wren House’s unofficial canine mascot whom Wortendyke adopted a few years ago, sniffed at hands and mingled.

“We want to make sure anything we do is responsible,” Thoeny said. “We’re always trying to be ... aware of where that water is coming from.”

In the Valley, we do drink recycled water and use it in our homes, but indirectly. Our water comes from rivers or underground aquifers, into which treated wastewater is regularly discharged. Las Vegas, for example, puts treated effluent into the Colorado River, which is brought to the Valley through the Central Arizona Project.

Reclaimed wastewater water is used primarily for cooling the Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant, recharging aquifers below ground, irrigating (how else could Scottsdale golf courses get so green?), or rehabilitating ecosystems.

But water from rivers and aquifers is growing more scarce. This applies not just in the Valley, in Arizona, or in the Southwest, but around the country and the world, thanks to climate change and the unquenchable thirst of humans.

Despite a wet winter, the Southwest is entering its third decade of one of the most severe droughts on record. The seven states that draw water from the Colorado River recently wrapped up hard-fought negotiations to take less from that river. Across the U.S., people are drilling wells ever deeper in pursuit of shrinking supplies of groundwater.

“Potable water supplies in Arizona will be stressed over the next few decades,” noted a 2018 report by the National Water Resource Institute on direct potable reuse in Arizona. “Water resource reliability is a growing concern.” Cities are forced to make better use of the water they do have, including underappreciated wastewater.

Think it sounds gross? You’re not alone. The idea of washing and cooking with, or drinking, water that might at some point have passed through someone’s toilet seems to reflexively generate resistance and apprehension. Nose-wrinkling slogans like “toilet-to-tap” and “flush-to-faucet” have not helped increase the appeal of direct potable reuse.

But in recent years in the U.S., recycled water has gained recognition as a practical, vital source. Engineers are combining water-treatment technologies in ever-more-effective ways, and costs have dropped. Treating wastewater to drinking water standards is typically cheaper than desalinating water. Legal requirements are evolving. In 2018, revised Arizona regulations opened the door, for the first time, to permitting for direct potable reuse.

Homes in the Valley are far from needing this water now, while other places in Arizona with severe water scarcity could already benefit from this extra supply. Flagstaff is actively working toward direct potable reuse.

Sarah Porter, the director of the Kyl Center for Water Policy at Arizona State University, said that when or whether a community will need to rely on recycled water for use in homes is extremely contextual, shaped by economic and financial considerations and water security. Some cities lack the infrastructure or financial capacity to build pipes and treatment plants. For others, like San Diego, direct potable reuse has proved to be more economical than other options, like desalinating sea water.

"Who needs it? It depends on how close any particular city is to the limits of its current supplies. And whether or not it makes sense depends on the city,” Porter said. “I think it’s urgent for cities to be able to have [direct potable reuse] as an option in their portfolios."

For some cities, especially ones that are growing quickly, "it’ll be a really key part." For others, it's less urgent. "There's no reason why everyone should suddenly be doing direct potable reuse," she said. "But we should be able to, and in time, we will."

One of the trickiest obstacles to using reclaimed water, experts often say, is our attitude.

The water factory

On a Wednesday morning in mid-July, about two dozen local brewers, including Thoeny, sat in a conference room at the Scottsdale Water Campus, a low-slung advanced water treatment facility just north of the 101 Pima Freeway. They sat patiently as Nicole Sherbert, a spokesperson for Scottsdale Water, played an introductory promo video. After a brief presentation would be a tour of the facility itself — a rare opportunity, Sherbert emphasized. She was open about the reason Scottsdale is doing all this: It wants the brewers’ help to lift recycled water .

“We got the rule changed,” she said, referring to last year’s lifting of the ban on direct potable reuse. “Now, we have to deal with perception change.”

That’s where the brewers come in.

Persuading skeptics via beer that recycled water is safe and good is not a new idea. In fact, it seems to be one of the few strategies that cities have deployed in their efforts to clean up recycled water’s image. In the last two years, Tucson, San Diego, and Boise, Idaho, all have held brewing challenges using recycled water. Last year, a brewery and research institute in Sweden combined forces to trot out a wastewater-based brew, called PU:REST.

Scottsdale hopes to join those cities in November, provided it gets a permit on time from the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality. The permit would allow it to use the water at one event per year and offer samples during tours of its facilities, and it would be the first-ever such permit to a facility in Arizona for direct potable reuse, according to ADEQ.

Before the permit comes through and the brewing kicks off, Scottsdale wanted to educate brewers about how its facility cleans the water they’ll be brewing with.

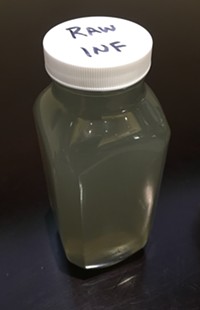

Allan Davidson, Scottsdale’s wastewater treatment manager, walked to the front of the room and picked up a small bottle of cloudy water, the first in a row of four vessels holding increasingly clear water.

Raw influent contains “all the things you can imagine, coming from toilets, showers, laundries,” said Davidson, holding up Bottle Number One.

The first step in the treatment process is to push that water through a mechanical filter called a bar screen, he said. From there, it enters settling tanks, where small bits of junk and sediment sink to the bottom and are removed.

Next, the water goes into an aeration basin teeming with microorganisms that further break down solids and organic matter. “We like to see a good mixture of ciliates, rotifers, and maybe a few nematodes,” Davidson said.

From there, the water enters a second settling tank to remove the microorganisms. It emerges clear and clean-looking, but it still contains fine dissolved materials that amoebas cannot remove, so it is forced through a disk filter resembling a shag carpet. The filter has openings of 10 microns — that’s 0.00039 inches, if your mind can downscale that far — that remove even more junk, and then the water is treated with chlorine and ozone.

Scottsdale Water Reclamation Director David Walby joined Davidson for the presentation. He held up a bottle with water from that stage in the treatment process, now considered tertiary effluent, and inspected it.

“I don’t see any floaties in there,” he said.

That water is not potable, meaning it’s not safe to drink, but it is clean enough to water golf courses and sports fields, or to be pumped into aquifers, Walby said. Or, it can go to an advanced treatment plant — paid for by Scottsdale golf courses, which are picky about their water — which the brewers were about to see, for more filtering and disinfection.

Before this water can be drunk, it is microfiltered and treated with reverse osmosis and ultraviolet light.

Elizabeth Whitman

Walby, Willy Wonka-like, led them into the Microfiltration Facility, onto a walkway above a depressed floor with rows of bright-blue pumps. Each was pushing water to modules containing dense bundles of 10,000 hollow fibers that are like straws, but peppered with holes 0.04 microns in diameter — 300 times smaller than a human hair — that catch silt, bacteria, and viruses, all of which are periodically removed through back-washing and scouring, he explained.

The brewers followed Walby out of the Microfiltration Facility and outdoors, onto the warm expanse of concrete that led to the Reverse Osmosis building. There, water was forced into tubes wrapped tightly in semipermeable membranes, like rolls of paper towels. Those membranes have holes of 0.0004 microns, which catch salt and ions as water seeps outward.

Finally, the water is further disinfected with ultraviolet light, which breaks down compounds and rips up any remaining cellular material using a chemical reaction called photolysis. After the water passes through a granulated activated carbon filter, it finally meets drinking water standards. The brewers will receive 1,000 gallons of that water to brew with. Water for future tasting events will go through a calcite mineralization process (for taste) and a chiller before being dispensed from a fountain.

“We can’t offer samples,” Walby said apologetically, citing permitting. (ADEQ expects to issue the permit in September.)

Later, when Walby’s back was turned, one brewer motioned to another person to sneak a sip from the fountain. The person declined.

Guy Carpenter, the vice president of Carollo Engineers and a past president of the national WateReuse Association, said that the technology to treat wastewater to drinking-water standards is not new. What has changed is the combination of those technologies, like reverse osmosis, ultrafiltration, and oxidation through ultraviolet light treatment, to catch microbes and kill pathogens effectively.

"With [direct potable reuse], we have to be respectful of the original source, which is very, very high, obviously, in human bacteria," he said. "We've got a little bit more redundancy built in. It's almost over-designed, in terms of protecting public health."

Those processes also remove pharmaceuticals and other trace organics that aren't currently regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency, Carpenter added. "There's a benefit to using these technologies," he said.

The one thing that worried Carpenter, in terms of contamination, is a problem that is not caused by wastewater. PFAS and other groups of nonstick chemicals are found in a lot of consumer products and can have serious health effects. They've been dubbed "forever chemicals" and they are everywhere, he said.

Cheers

In 2017, when Wren House joined the brewers' challenge led by Pima County, it served the hazy IPA along with informational posters and documents about the recycled water the beer came from. That year, the county got a special permit from ADEQ to build a mobile unit for water treatment.“I think 100 percent of people really liked it,” Thoeny said. He called across the room to a man about to walk out, stopping him in his tracks. “Tyler was the bartender."

“No one was weird about it, right?” he called to Tyler.

“No,” Tyler called back.

Thoeny recognized the role that breweries like Wren House can play in changing public perceptions about recycling water.

“That’s the relationship we build with the customer — they trust us,” he said. “It’s a very cool way of at least demonstrating a way to get clean, usable, drinkable water out of wastewater.”

For the November competition, they plan to brew a lager.

Sherbert, the spokesperson for Scottsdale Water, said that the city hadn’t conducted any public opinion surveys on drinking recycled water.

But the city runs regular citizen academies to educate the public on water, and she said that during the most recent session, people brought up the topic on their own. “Why can’t we drink this; why not let people drink this?” they wanted to know.

Studies and opinion polls elsewhere have generated a mix of findings. It remains unclear how successfully these small-scale brewing challenges shift people's perceptions on drinking reclaimed water.

A 2017 poll of 1,500 Californians conducted by researchers at Stanford University found that people were most resistant to the idea of coming into direct contact with the water. They were more open to the idea of using the water for purposes like irrigation and toilet-flushing. A slightly smaller survey by researchers at the University of Nevada in Reno, published earlier this year, found respondents to be split in their willingness to drink reclaimed water. Thirty-five percent were willing, 38 percent were not, and 26 percent were unsure.

Porter, the Kyl Center director, remembered tasting the different beers two summers ago, during Arizona's first recycled water brewing challenge.

"I tasted a lot of different beers and forgot all about the fact that it was DPR," she said. "I thought it was very clever.”

But she was quick to point out that it's also easy to forget that we're already drinking recycled water that has been filtered through nature. If people think about that, "it's easier to cope with," she said.

"We have to continually adapt to our improved understanding of water, and what is safe," Porter added. "We're still adapting."