The news that black community leaders are calling on Governor Doug Ducey to take down six Confederate memorials spread around the internet on Monday night, prompting people around the country to ask, "Wait, Arizona was part of the Confederacy?"

The answer is yes, kind of: Southerners who settled here briefly claimed the lower half of the state (which back then was only a territory) for the Confederate States during the Civil War. During that time, the federal government never recognized the fact that a portion of the Arizona Territory had abandoned the Union.

But Arizona's Confederate memorials don't date back to that era.

They tell another, even less well-known story: one of white Southerners who moved to Arizona in the post-World War II era and brought their fondness for intimidating black citizens with them. The state's oldest Confederate memorial was dedicated nearly 80 years after the Civil War ended, in 1943. The newest, shockingly, went up in 2010.

For decades after the end of the Civil War, there was little effort made to commemorate the fact that Arizona had been on the wrong side of history. As historian William Stoutamire details in the Journal of Arizona History, most supporters of the Confederacy either left Arizona or were arrested for treason after Union troops from California showed up in Tucson.

When the Civil War came to an end, people who had sided with the Union returned to southern Arizona, vastly outnumbering the remaining Confederate sympathizers. The Arizona chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy didn't get started until 1919 — some 30 years after similar groups honoring Union veterans had been established here.

And so-called heritage groups intended to honor the Confederacy weren't exactly welcomed with open arms. In 1928, when the Arizona Pioneers' Historical Society and the Southern Pacific Railroad dedicated a monument to the three Union soldiers who had died at Picacho Pass, they deliberately declined to invite the United Daughters of the Confederacy to the ceremony.

It wasn't until the mid-1950s that Confederate heritage groups became a significant presence in Arizona, which Stoutamire attributes to the state's population boom during that era.

"As thousands of Southerners moved to a drier climate, they brought with them an identity grounded in the constant presence of Confederate symbols," he writes. "Confronted with Arizona's secessionist history, they felt the need to memorialize and commemorate the Confederacy's attempted extension into the Southwest."

By then, the civil rights movement was ramping up across the country. Not coincidentally, honoring the Confederacy suddenly became a popular pastime for white people with a tenuous connection to the Old South.

It was hardly a fringe movement: When the Civil War centennial rolled around in 1961, Arizona recognized the anniversary by flying the Confederate flag over the State Capitol. Politicians including Governor Ernest McFarland frequently spoke at United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of Confederate Veterans events.

But the Confederacy that these events commemorated was that of the plantations back East, not the dusty, disorganized Arizona Territory. During the state's Centennial Ball, Tucson's Ramada Inn was transformed into an "antebellum flower garden" with peach trees and women dressed in elaborate ruffled silk dresses straight out of Gone with the Wind.

That nostalgia for a lifestyle that never existed in Arizona in the first place needs to be understood in the context of the Freedom Riders and the nationwide push for racial integration, Stoutamire says.

"It’s a direct response to federal desegregation, Brown v. Board of Education, all the policies coming down on the federal level," he tells Phoenix New Times.

"The African-American population in Arizona is going to read [the choice to fly the Confederate flag over the State Capitol] as a very clear statement that the government is hostile to black interests, and specifically civil rights.

"Even if that’s not the intended message — and I would argue that it is — that’s how it's going to be received."

After the anniversary of the Civil War passed, Arizona's Confederate heritage groups went into a decline.

Stoutamire says that was part of a nationwide trend, attributable both to the reality that new generations were that much further removed from the memory of the Civil War, and the growing distaste for the fact that groups like the Sons of Confederate Veterans had become more explicitly political — and often racist.

In the 1990s, however, the Arizona chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans experienced a resurgence, and once again began erecting monuments to the Confederacy.

"Arizona is odd in that they’ve put up monuments in the last 20 years," Stoutamire says. The fact that people don't typically associate the state with the Civil War may have allowed Confederate heritage groups to fly under the radar and do so without much controversy, he suspects.

And focusing on Arizona's choice to join the Confederacy is a strategic choice for those groups.

"What you see nationwide among Confederate heritage groups is this desire to espouse the supposedly multicultural heritage of the Confederacy," he explains. "They like to claim that African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, and Native Americans were part of the Confederacy, in an attempt to say it couldn’t have possibly been about slavery."

The fact that Arizona wasn't involved in the slave trade — and that a diverse group of people within the territory wanted to leave the Union for various different reasons — makes it a historical outlier, and one that's appealing for Confederate heritage groups to focus on, Stoutamire says.

"It's this desire to make it look like the Confederacy was this welcoming society — when in fact it was founded on the basis of white supremacy."

Here are the six Confederate memorials that the East Valley NAACP has identified, and their histories:

Confederate Memorial in the Southern Arizona Veterans’ Cemetery, Sierra Vista: Erected in 2010 with support from members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Arizona Confederate Veterans Monument in Greenwood Memory Lawn Cemetery: Dedicated in 1999 by a local chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Monument at the graves of four Confederate soldiers killed during a skirmish with the Chokonen band of the Chiricahua Apache, Dragoon Springs: The “monument” here is more of a historical marker placed there by the U.S. Forest Service — in cooperation with the Arizona Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans — in 1999.

Confederate Veterans Monument in Wesley Bolin Memorial Park, in front the state capitol: Erected by the United Daughters of the Confederacy in 1961.

Jefferson Davis Highway, U.S. Highway 60 at Peralta Road, Apache Junction: In 1913, the United Daughters of the Confederacy came up with a plan for a transcontinental highway named for their hero, Confederate president Jefferson Davis.

Arizona’s Jefferson Davis Highway is one small segment of that route, which was supposed to run coast to coast across the southern United States before ending in Washington, D.C.

While it didn’t end up getting completed as planned, that didn’t stop the Daughters of the Confederacy from erecting a highway marker along the route 30 years later, in 1943.

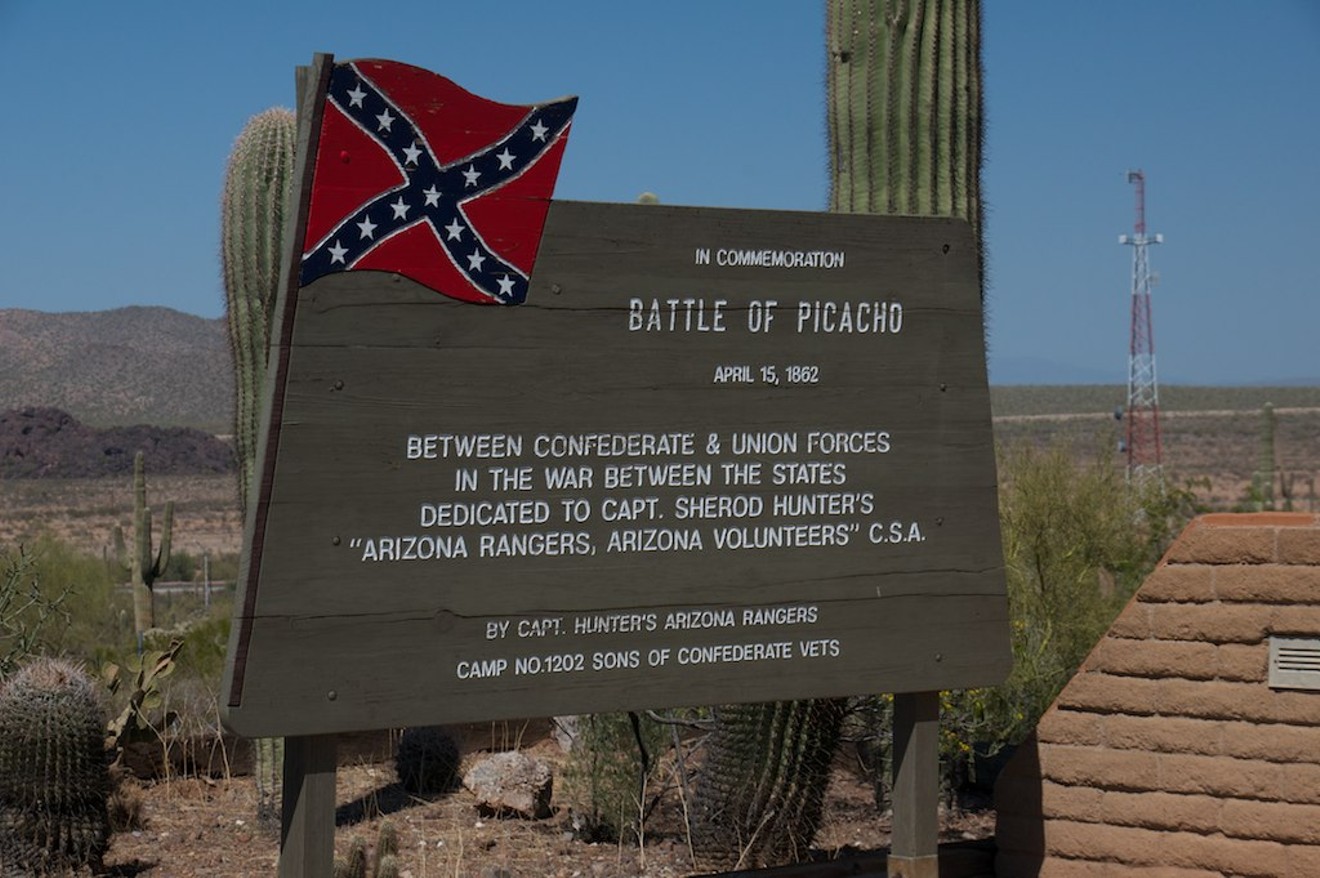

Battle of Picacho Peak Memorial, Picacho Peak State Park: There’s a number of monuments and historic markers here, commemorating a relatively small skirmish often touted as "the westernmost battle of the Civil War."

In fact, historian William Stoutamire notes, "there are now more monuments and markers dedicated to the 'Battle of Picacho Pass' than the total number of troops killed in the actual engagement."

The oldest of these monuments memorializes the three members of the Union cavalry from California who died in the skirmish. It was erected in 1928 by the Arizona Pioneers Historical Society and Southern Pacific Railroad, replacing a dilapidated cross and grave marker.

In 1984, the Children of the Confederacy, United Daughters of the Confederacy, and Arizona Historical Society added a plaque of their own to the monument, “dedicated to those Confederate frontiersmen who occupied Arizona Territory, C.S.A., created by President Jefferson Davis.”

Another Confederate memorial at the park, which refers to the Civil War as "the War Between the States," was placed there by a local chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans in 1958.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]