Like many Southern states, Arizona had a law on the books for six decades that required all would-be voters to take an English literacy test first. In Alabama, tests like these were used to disenfranchise black voters; in Arizona, the goal was to keep Spanish speakers from voting.

The idea appears to have originated in the pages of the Arizona Republican, which would later become the Arizona Republic. “No person should be permitted to vote in Arizona unless he can read a paragraph of simple English,” the paper declared in an unbylined 1905 editorial. “There is a foreign element in our voting population which is both illiterate and ignorant of our institutions. This element is neither Democratic nor Republican. It is for sale — openly and notoriously for sale.”

Eleven days later, a subsequent editorial laid it out even more bluntly: “We are referring, of course, to the ignorant Mexican vote. We speak in plain English. And discussing the question from the plane of the political interests of the legislators, what have they to fear from the Mexican vote in any event? It is a notorious fact that the Mexicans of the ignorant and migratory class — the class which should be denied the franchise — do not vote unless they are paid for their votes.”

Not all people with Mexican ancestry fell into this category, the anonymous writer acknowledged:

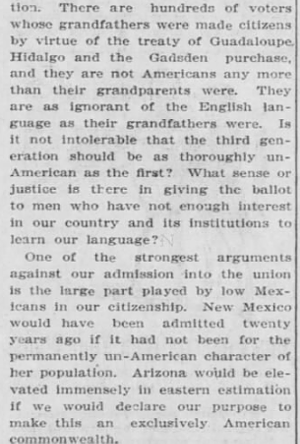

But there is a large Mexican element of the low class which properly has no place in our citizenship. It is an outrage that this element should be able to offset, vote for vote, the citizens who are building up the territory and paying the taxes. We provide a free public school system, at vast expense, and we have a law which is supposed to be compulsory in requiring all children to be sent to school. But this element refuses to take advantage of our fine system of education. There are hundreds of voters whose grandfathers were made citizens by virtue of the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Gadsden purchase, and they are not Americans any more than their grandparents were. They are as ignorant of the English language as their grandfathers were. Is it not intolerable that the third generation should be as thoroughly un-American as the first? What sense or justice is there in giving the ballot to men who have not enough interest in our country and its institutions to learn our language?

Four years later, they got their wish.

In 1909, Arizona’s territorial legislature assembled in Phoenix — “amid democratic gloom,” the Arizona Republican wrote. Republicans, who back then were the more liberal party, made up a majority of county supervisors and county officers. The territory had elected a Republican delegate to Congress, and a Republican governor. They only place were Democrats had a majority was in the legislature, which the Republicans had overlooked.

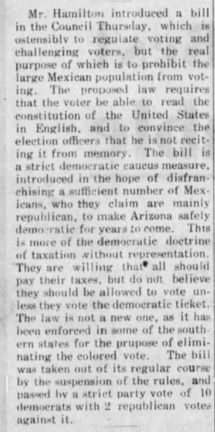

The Democrats promptly set out to push through a law requiring voters to be able to read a section of the United States Constitution in English and convince elections officers that they weren’t reciting it from memory. Though described as an “educational qualification,” it primarily targeted citizens of Mexican descent who’d been educated in Spanish.

The Coconino Sun was blunt about the real purpose of the legislation: “The bill is a strict Democratic caucus measure, introduced in the hope of disenfranchising a sufficient number of Mexicans, who they claim are mainly Republican, to make Arizona safely Democratic for years to come.”

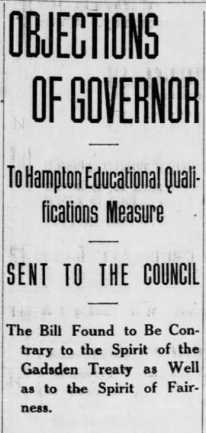

Arizona’s governor then, Joseph H. Kibbey, was not interested in passing any such law. He was an Indiana native who’d been educated at a Quaker college and was unusually progressive for his time. He had fought to get the mining industry to pay its fair share of taxes while also vetoing legislation that would have segregated Arizona’s schools.

“To say that all men in Arizona who cannot read the constitution in the English language, are so ignorant and illiterate that they ought to be denied the right of suffrage, is grossly unjust,” he wrote in a message to the legislature. “For generations there have been settlements in the older of states of the union where the English language was seldom, if ever, spoken — where the German, or the French, the Scandinavian, or the Hebrew are almost the only languages spoken.

"Because they do not speak or read or write English is not to denounce them as ignorant, illiterate, and hence venal, dishonest, and corrupt. Such a conclusion would be an unjust imputation against thousands of the best, most honest, most industrious and desirable citizens of our free, cosmopolitan country.”

Kibbey also pointed out that when the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, making Arizona part of the United States, most residents were (naturally) Mexican and Spanish-speaking.

“It would have been gross injustice and a direct violation of the spirit of the treaty to have denied them any of the right of American citizenship because they could not speak and read the English language,” he argued. “I do not deny that they should have as speedily as possible learned the language of their adopted country. But it seems to me some regard must be had for conditions.”

On top of all that, Kibbey added, there clearly was no way to determine whether someone was reciting the Constitution from memory rather than reading it off the page. Leaving that up to election boards, he warned, “makes it easy for admission of fraudulent and for the exclusion of honest voters as partisan interest may dictate or suggest.”

Kibbey ended up vetoing the bill not once, but twice. Both times, the legislature voted to override him. The second time around — which was only necessary because of a clerical error — supporters tried to argue that the law was based on a similar provision in Maine’s constitution.

But, Kibbey pointed out, when Maine introduced literacy tests, it specifically said that the tests couldn’t be used to disenfranchise people who had voted in the past, or were over the age of 60. That meant that the descendants of French colonists weren’t affected.

“In Maine, no more rapid progress had been made in substitution of English for the French language than has been made in Arizona of the English for the Spanish,” he wrote. “Indeed probably the transition has not been as rapid in Maine as it has been in Arizona.”

By 1910, the law was in full effect. When city elections rolled around, the Arizona Daily Star warned, “Every person who attempts to vote who cannot read a section of the constitution of the United States and write the English language will be arrested on the spot and prosecuted as the law provides.”

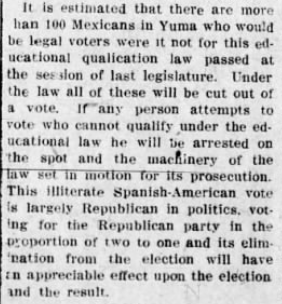

Blocking people who weren’t entirely fluent in English from voting appears to have worked exactly as intended.

“It has been estimated that there are more than 100 Mexicans in Yuma who would be legal voters were it not for this educational qualification law passed at the session of the last legislature,” the Star noted. “This illiterate Spanish-American vote is largely Republican in politics, voting for the Republican party in the proportion of two to one and its elimination from the election will have an appreciable effect upon the election on the result.”

That same year, The Oasis, a newspaper based in Nogales, reported:

The working of the alleged “educational qualification” was shown in the municipal election in Nogales on May 23rd, when a well known merchant in Nogales was challenged by the Democratic challenger and turned away from the polls without voting because he could not read a paragraph in the Federal Constitution. Yet that man, a naturalized citizen of the United States, owns and conducts two stores, in which are carried stocks that are worth at least $30,000; he reads and writes fluently two languages and can speak sufficient English to get along in a way in transaction of business. He is a good, law abiding citizen and a credit to any community. Had the constitution been presented to him in Spanish or Syrian he could have read and interpreted its meaning easily. Another man, who has lived in Arizona all his life, and became a citizen by virtue of the provisions of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and owns property on which he pays taxes, was challenged also and his vote shut out by force of that same inequitable and unjust enactment of the last Arizona legislature.

Plenty of Anglos criticized the practice of turning away otherwise qualified voters, but were unwilling to find fault with the systematic disenfranchisement of black men in the Deep South. In 1910, Governor Richard E. Sloan, who had succeeded Kibbey, wrote a letter to the chair of the local Democratic Campaign Committee contending that the literacy test was “unjustly discriminatory, racial in in its application, and as such is to be condemned.” If voters had to be subjected to a test, he argued, it should be one that didn’t favor one ethnic group over another.

But, he wrote, “The exception to this, so far as recent legislation is concerned, is found in the laws of certain Southern states where the negro population is excessive, and where the effort is avowedly racial in its object and intended to insure the dominancy of the white race. As the Mexican vote in Arizona does not exceed 10 per cent of the whole and is relatively growing less, it is idle to suggest that Anglo-Saxon supremacy is here in danger even remotely.”

Similarly, the Arizona Republican — which by then had changed course to oppose the law — claimed that in the South, “a majority of the voters are densely ignorant negroes, who, in the hands of unscrupulous politicians, could be converted into an engine which would wreck those states and overwhelm the intelligent population. There is no such danger in Arizona, and every year we are constantly removed from any such peril if it ever existed.”

Despite these claims, racial anxiety does appear to have motivated Arizona’s voting restrictions. While the territorial legislature was debating the merits of introducing the English literacy test, Arizona was fighting to be recognized as a state. And, initially, the Arizona Republican had argued that preventing Mexican-Americans from voting would help with that process.

“One of the strongest arguments against our admission into the union is the large part played by low Mexicans in our citizenship,” their editorial noted. “New Mexico would have been admitted twenty years ago if it had not been for the permanently un-American character of her population. Arizona would be elevated immensely in eastern estimation if we would declare our purpose to make this an exclusively American commonwealth.”

But when Arizona finally did become a state in 1912, Congress removed all mentions of a literacy test from the state’s new constitution. Several prominent Arizona residents had traveled to Washington, D.C., to testify before the U.S. Senate’s Committee on Territories, and urged them to do exactly that.

Robert E. Morrison, a Prescott lawyer, had estimated that as many as 1,800 voters who had lived in Arizona for decades would be disenfranchised by the law. John Lorenzo Hubbell, the owner of Hubbell’s Trading Post in Ganado, testified that it would disfranchise 250 out of 350 voters in Apache County, where he lived. (Those numbers did not include Native Americans, who were banned from voting until 1948.)

“As a rule, in our county, out of three hundred and some voters, two hundred and fifty or more vote the Republican ticket,” Hubbell told the panel of senators. “It has created throughout the Territory a feeling that Apache County sends the only sure Republican members to the council and house at every election; and it is my candid opinion, without mincing matters in any way, that the Democrats of the Territory felt that there should be some means of curtailing the influence of our county in territorial affairs.”

Only Marcus Aurelius Smith, Arizona’s delegate to Congress, argued in favor of keeping the restrictions in place. The goal had been to prevent voter fraud, he claimed, not to prevent anyone from voting:

Every Mexican from 25 to 30 years of age in my part of Arizona and who really lives there can read English, but we have thousands of Mexicans and others traveling around from railroad to railroad, doing work for them, and the purpose of the legislature, I think, was to confine the vote in Arizona to the citizens of the United States who live in Arizona. We have a great register, and a man only has to register that he is a citizen of the United States and swear to it, giving his name and residence. He gets on the great register. Of course, there is a penalty against false registration, but that is the last time that fellow will ever be seen in Arizona, and within six or seven or eight months of registration you have thousands of men imported there for another country, working on the railroad. These men pick up and go home whenever they please. They do not belong to our country at all.

Almost immediately after becoming a state, Arizona passed a law subjecting all voters to a literacy test, which was identical to the one that Congress had just repealed.

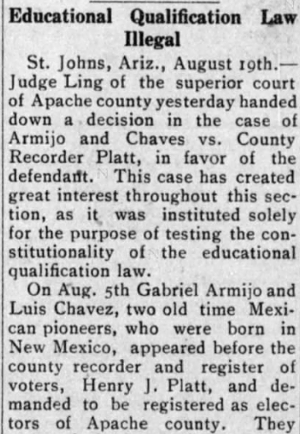

In August 1912, Gabriel Armijo and Luiz Chavez — described in the papers as “wealthy Mexican Republicans” whose families had been in Arizona since before the Civil War— showed up to vote and refused to take the test. Chavez had been educated in English, but refused to take the test on principle, arguing that he had voted for the past 30 years and had a right to continue to do so.

Both were rejected, and they promptly sued. A Superior Court judge ruled that the Apache County recorder had been within his rights to refuse to register both the men.

Exactly how many people were kept from voting because they couldn’t (or wouldn’t) pass the test is unclear.

“The process was one of not attracting people to vote,” recalls Roberto Reveles, a longtime civil rights activist whose family members were blocked from voting during the 1940s and 1950s because of the literacy test.

“If you know that you’re going to be facing a difficult task in exercising your right to vote, well, a lot of people even today don’t show up to vote. Pile on top of that the notion that, if I go to vote, I’m going to jump through some hoops in a language that I’m not totally in control of. It’s hard to quantify exactly how many people did not participate because of that. I’d say that a lot of people didn’t, but I can’t quantify it.”

Equally problematic, Reveles adds, was the fact that voting literature and ballots were only printed in English.

“It was very difficult to encourage people to vote because it just seemed like an overwhelming problem with a lot of the older folks in particular,” he remembers. “My own grandfather was literate — he had the skill of reading in both Spanish and English — but even he would talk about how much of a challenge it was to be fully informed in the voting process.”

And, for decades, there weren’t many candidates who Mexican-Americans even wanted to vote for.

“Mexicans didn’t vote a lot,” says Frank Barrios, the author of Mexicans in Phoenix. “You could vote, but there were never any Mexicans you could vote for. It was always Anglos who were running. Today, the Republican party is very anti-Mexican, so it’s tough to be a Republican, but in those days, both parties were anti-Mexican.”

When Mexican-American veterans returned home from World War II, they were no longer willing to put up with segregated neighborhoods, schools, churches, movie theaters, and pools. Quite a few decided to run for public office.

“It started to change the composition of the people who would come out to the voting booth,” Reveles recalls.

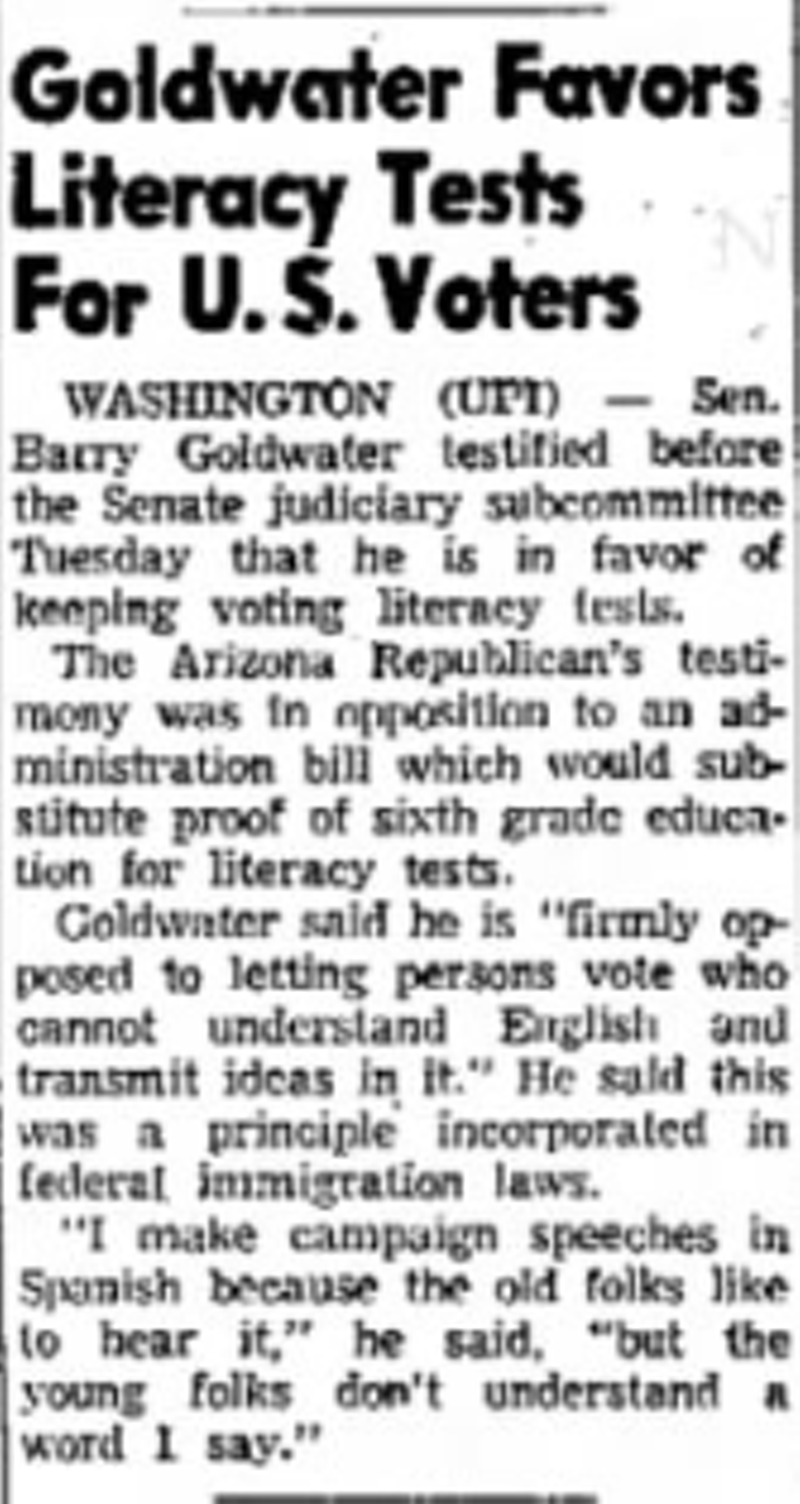

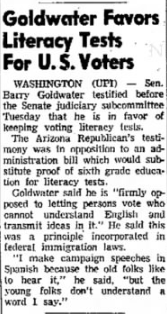

That political shift coincided with the civil rights movement in the South, and by the 1960s, Congress began talking about getting rid of literacy tests and other forms of discrimination aimed at nonwhite voters. In 1962, Senator Barry Goldwater testified in defense of keeping the tests, telling the Senate Judiciary Committee that he was “firmly opposed to letting persons vote who cannot understand English and transmit ideas in it.”

In the Southwest, English was becoming more and more widespread, he argued: “I make campaign speeches in Spanish because the old folks like to hear it, but the young folks don’t understand a word I say.”

Yet during this same period, Republicans were using literacy tests to intimidate nonwhite voters in south Phoenix. As part of what was known as “Operation Eagle Eye,” they stationed themselves as the polls and routinely challenged black and Latino voters who were thought to be likely to support Democrats. One of the young lawyers leading the effort was William H. Rehnquist, who later became the chief justice for the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 2000, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette columnist Dennis Roddy interviewed Manuel “Lito” Peña, a former Arizona legislator who died in 2013, about Rehnquist’s role in Operation Eagle Eye. Roddy later wrote:

Lito Pena is sure of his memory. Thirty-six years ago he, then a Democratic Party poll watcher, got into a shoving match with a Republican who had spent the opening hours of the 1964 election doing his damnedest to keep people from voting in south Phoenix.

"He was holding up minority voters because he knew they were going to vote Democratic," said Pena.

The guy called himself Bill. He knew the law and applied it with the precision of a swordsman. He sat at the table at the Bethune School, a polling place brimming with black citizens, and quizzed voters ad nauseam about where they were from, how long they'd lived there — every question in the book. A passage of the Constitution was read and people who spoke broken English were ordered to interpret it to prove they had the language skills to vote.

Stopping minorities at the polls was once a common practice for conservatives, Adam Diaz, the first Hispanic city councilman in Phoenix, told the Arizona Republic in 1991. (Diaz passed away in 2010.) “Many of our people, very innocent, just walked off,” he said. “They were kind of intimidated.’”

Despite opposition from Senator Barry Goldwater, the Civil Rights Act passed in 1964 and prohibited the use of literacy tests under certain circumstances. The Arizona Republic claimed that such tests had been “seldom invoked” in the state, but a story in the Tucson Daily Citizen that same year suggested otherwise:

Despite announced Republican plans to conduct an anti-vote-fraud “alert” nationally, Pima County election officials predict fewer voters will be challenged here Tuesday than were two years ago. The net result, they indicate, will be a gain in Democratic votes, thanks to the new Federal Civil Rights Act. In the past, reports Manuel Cervantes, head of the Pima County Election Bureau, most challenges were based on state literacy requirements, and were heaviest in predominantly Mexican-American precincts. The Mexican vote has historically gone Democratic.

In 1970, the Voting Rights Act was amended to outlaw all use of literacy tests as a prerequisite for voting. But Arizona refused to give up that easily. Attorney General Gary K. Nelson announced that the state wouldn’t comply, which in turn prompted a federal lawsuit.

The Supreme Court ultimately ruled in the federal government’s favor, declaring Arizona’s literacy test unconstitutional. It was finally repealed by the legislature in 1972, nearly 60 years after it was first dreamed up by a group of white Democrats hoping to disenfranchise their fellow citizens.