As they walked to the sink, she assumed they were there to do basic repairs. “I told my class, just put your eyes on me and focus, because this is really important,” Boileau-Stockfisch recalled.

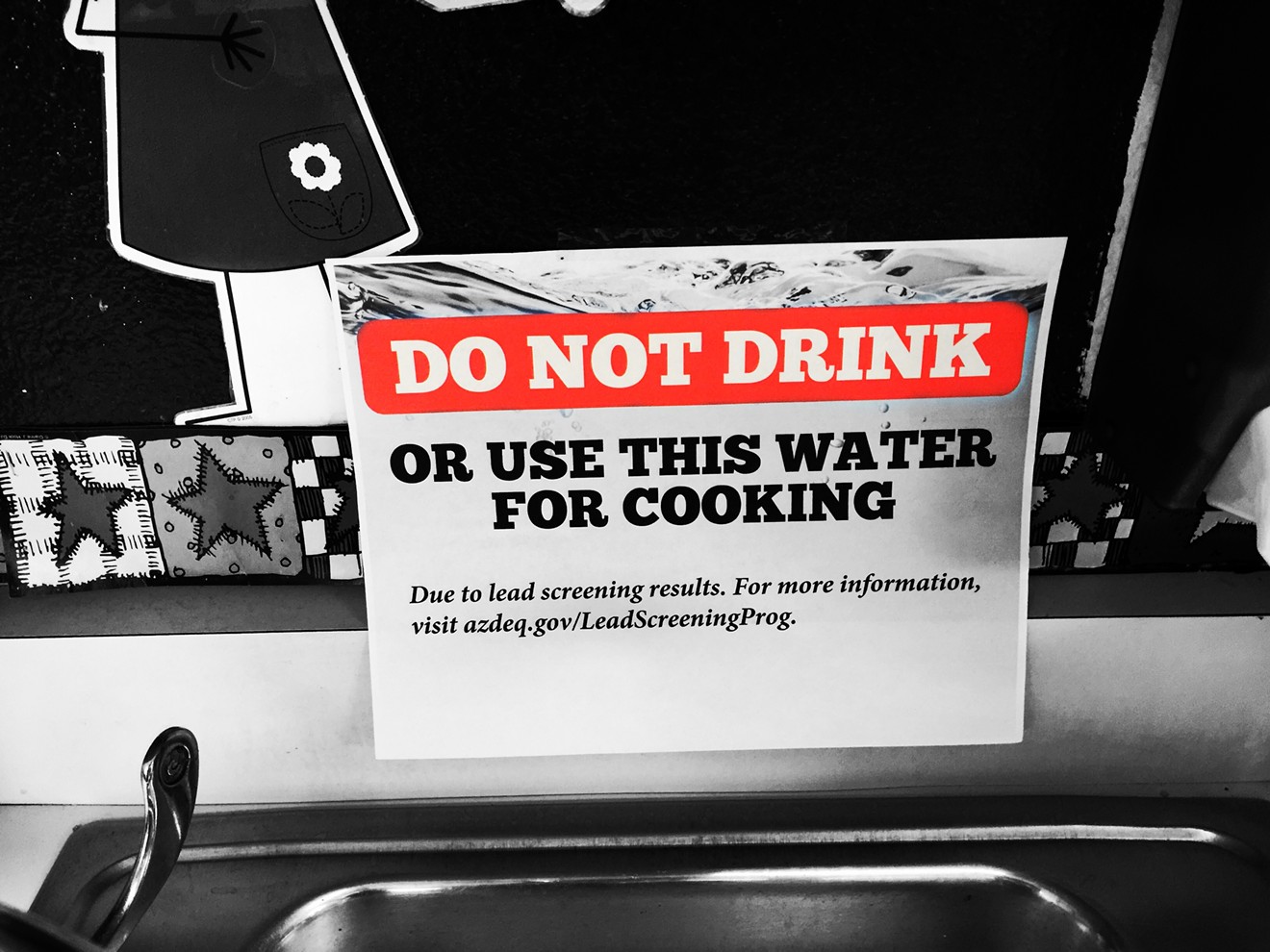

Once the students were occupied with their writing assignment for the day, Boileau-Stockfisch turned her attention back to the sink. She noticed the repairmen had taped a sign over it: “DO NOT DRINK OR USE THIS WATER FOR COOKING.” Below, smaller text said it was due to lead screening results.

Immediately, Boileau-Stockfisch felt a sense of dread, her mind racing. I drink that water, she remembers thinking. I make Crystal Light every day, sometimes twice a day. As children, her daughters drank water from the classroom sink for years, anytime they visited her school, where Boileau-Stockfisch taught in the same classroom for 18 years.

“We didn’t do water bottles. They just drank out of my faucet,” the 55-year-old teacher said.

Later on May 17, sometime around recess, Boileau-Stockfisch received an email with the initial lead test results from her sink. As she read the small print that listed her classroom’s results, Boileau-Stockfisch felt physically ill. Water from her sink had tested for 500 parts per billion of lead — 33 times higher than the federal limit.

“I just immediately went to the bathroom and got sick,” she said.

Her classroom’s three-digit lead level outpaced the other tests that took place at Entz Elementary last April, a season that saw the Department of Environmental Quality conduct the first voluntary lead testing at schools across Arizona.

Fifteen parts per billion serves as a federal standard for the acceptable level of lead in drinking water; as a result, ADEQ chose 15 ppb as the cutoff where the department would shut off the tap and inform families that elevated lead had been discovered in school drinking water.

“I just immediately went to the bathroom and got sick.”

tweet this

Other water samples from Entz Elementary tested during the first round between 5.5 to 9.3 parts per billion of lead. Only one other classroom, where one source had 21 ppb of lead, tested above the action level. But even that number was a far cry from Boileau-Stockfisch’s 500 ppb.

Confirmation testing, a second round designed to verify the initial lead results, also showed elevated lead levels when the water was first turned on at the sink. A first-draw confirmation test showed 1,300 ppb of lead, and a subsequent test after running the faucet showed a lead level of 1.5 ppb. The next day, a first-draw test showed another elevated lead level, this time at 95 ppb.

Based on these results, ADEQ determined that Boileau-Stockfisch’s lead problem stemmed from a fixture on the tap. The district replaced her sink’s fixture along with two others at Entz Elementary.

But the district never proactively reached out to families to tell them precisely how high the lead levels were in Boileau-Stockfisch’s second-grade classroom.

The school district sent a paper letter in student backpacks to Entz Elementary families on May 17 to let them know that testing had taken place. It sent another letter on August 14 to inform them that the water sources exhibiting high lead had been repaired and no longer showed elevated levels.

Neither letter mentioned the exact lead levels. The district eventually emailed families on July 12 to let them know of a website where, if they followed a URL in the message, they could view Entz's lead testing results.

The same day that her sink was shut off, Boileau-Stockfisch emailed Entz Elementary principal William Schultz to ask him when he first learned of the elevated lead level in the sink. Schultz replied to say that he only learned of the results that morning.

“I understand your concern having spent 18 years in this classroom,” Schultz wrote back.

“It is possible that this screening may not be accurate as we don't have multiple classrooms testing positive for lead,” he added. “I want to assure you that we will be forthright with any all information concerning this matter. I will personally do everything in my power to assist you.”

Mesa school district employees replace parts of Boileau-Stockfisch's classroom sink last summer.

Courtesy of Genevieve Boileau-Stockfisch

In her reply to Orrantia, Boileau-Stockfisch wrote, “Who else was informed of the testing updates? I am completely floored that anyone from Mesa Public Schools failed to update me with this information. I was implicitly clear that I was concerned and wanted to know the results immediately.”

Distraught from the lead findings and upset at how the school handled the elevated lead levels, Boileau-Stockfisch took a leave of absence last August from Entz Elementary. She can’t understand why the district didn’t inform families of the lead results in the same way they’d inform them if their child had been injured at school.

“They could’ve done so much more to be proactive,” she said. “They send a note home for every little bump to the head, for liability. But 1,300 parts per billion of lead in the water was not enough to notify everyone.”

The Mesa Unified School District says it responded to all of Boileau-Stockfisch’s concerns in a timely manner. Helen Hollands, the school district’s executive director for technology and communications, said, “There was never any district intent to withhold or in any way delay the delivery of the results to Ms. Stockfisch."

“I will say that there’s just a disparity between her need for immediate results and our sense of urgency in providing them,” Hollands added. “But there was never an intent to withhold or in any way prevent them from being released.”

Boileau-Stockfisch disagrees, contending that the school never proactively provided her with the confirmation testing results that showed 1,300 ppb of lead. She also says that the district never told her when the confirmation testing was scheduled to take place, and ignored her request for an investigation into how long lead might have leached into her water.

Hollands explained that all the lead testing in Mesa was carried out under the protocols from ADEQ, in conjunction with the Arizona Department of Health Services. She said the district followed “a very comprehensive communications protocol.”“We certainly did have a sense of urgency when we got high results."

tweet this

“We certainly did have a sense of urgency when we got high results, not only for preventing further drinking for those sources but also getting information out to parents that we had found higher lead content and we had taken certain actions,” Hollands said. “Normally, those letters and those things happened usually the day of or the day after receiving those results.”

But other parents grew agitated when they learned of the elevated lead. An impromptu meeting took place on July 11 between Mesa Associate Superintendent Peter Lesar, Hollands, Boileau-Stockfisch, her 28-year-old daughter, and several other parents. The ad hoc meeting happened because the parents weren’t able to address their lead concerns at a budget hearing — it wasn’t an agenda item.

Hollands and Boileau-Stockfisch agree that the meeting grew heated, but Boileau-Stockfisch was especially troubled. She says that Lesar was defensive from the start, and felt that his responses were rude and demeaning. (He did not respond to requests for comment.)

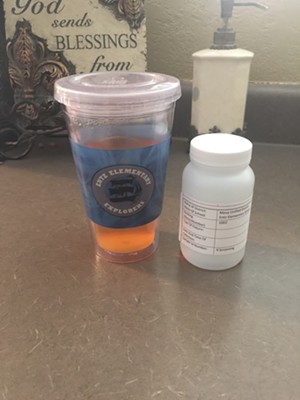

Boileau-Stockfisch would bring this bottle to school, shown here filled with Crystal Light, and would refill it at her classroom sink that later tested positive for excessive lead.

Courtesy of Genevieve Boileau-Stockfisch

In some ways, the meeting was the culmination of the disappointment and anger Boileau-Stockfisch felt toward the school district. It contributed to her decision to take a leave of absence from the job the following month, a job she had held for nearly 20 years.

“I cannot believe what happened in my classroom,” Boileau-Stockfisch said. “Especially when the district says, ‘We care so much about teachers, and we value children.’ I personally don’t feel that their actions did. It’s always people’s actions that speak the truth.”

Young children are at the greatest risk for lead poisoning, and people who have been exposed to lead often exhibit no obvious symptoms. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says, “No safe blood-lead level in children has been identified.”

Lead poisoning from sources such as paint, water, and toys can affect growth and development in kids ages one to six and presents risks for adults.

But the ADHS tried not to sound the alarm when it described the lead testing program in Arizona schools: “People’s exposure to lead in drinking water at a school is only a small part of their overall potential exposure,” ADHS wrote in an FAQ on the lead screening program last February.

Water that has been sitting in school pipes can show elevated lead levels once you turn the tap on again — in the morning, for instance. Continuous water flow throughout the day can reduce the amount of lead present in water when it exits the faucet, according to ADHS. But this is no comfort for Boileau-Stockfisch.

“The person who turned that water on first thing in the morning? Me, or my girls when they were younger,” she said.

When she would bring her children into the classroom regularly, they were around the ages of six to 10. “My job was to always protect them,” Boileau-Stockfisch said. “I thought I was doing that by having them with me in my classroom. That’s a hard thing to deal with.”

From a review of the initial lead screening in Mesa district schools last spring, 72 drinking water samples from sources accessible to students showed lead levels above 15 ppb. Of these samples, elevated lead was found in at least one water source at 37 different Mesa schools. Many of the schools had more than one water source with lead content above 15 ppb.

In total, ADEQ took around 1,250 water samples in the school district. The result from Boileau-Stockfisch’s classroom was among the highest lead levels discovered out of all the district’s testing.

Based on ADEQ’s data, Mesa public schools had a higher concentration of lead in its water compared to nearby schools. 10 percent of the initial samples in Mesa schools were above 15 ppb, while the county average was 5 percent. It was the same during the confirmation sampling: 41 percent of Mesa’s samples were above the limit, while Maricopa County saw 28 percent of its samples exceed 15 ppb.Elevated lead was found in at least one water source at 37 different Mesa schools.

tweet this

Erin Jordan, a spokesperson for ADEQ, said that the department used a “very conservative” threshold when labeling school water sources as containing elevated lead.

But ADEQ couldn’t provide any information on how long Boileau-Stockfisch’s sink might have been leaching lead into her drinking water. “That’s not really something we can say, unless a baseline was taken at that point,” Jordan said.

It’s a harsh reality. Because lead testing at Arizona schools only started in January 2017, Boileau-Stockfisch’s push for answers is riven with unknowns. Neither the school district nor the environmental agency can assuage Boileau-Stockfisch’s concerns about years of lead exposure from her classroom sink.

Before last year's statewide testing for lead in schools, all a worried teacher or parent would find is a black hole of information. With data that only goes back one year, you can't reconstruct a timeline of lead exposure — even if you've taught in the same classroom for nearly two decades.

Hollands, the Mesa communications director, echoed ADEQ when asked about Boileau-Stockfisch’s fears surrounding how long lead had contaminated sources of drinking water across district schools.

“To be honest with you, spring of 2017 is time zero for schools across the state of Arizona for lead testing in water,” Hollands said. “We could debate that all day, whether or not this should’ve been done in prior years. It wasn’t — there was no protocol for doing it.”

Hollands emphasized that the district shares Boileau-Stockfisch’s frustration. “It’s certainly frustrating to everybody,” she said. “We know what we don’t know, and we can’t go back on that.

“We can’t assume that no people were exposed to lead content as much as we can’t assume that everybody was,” Hollands added.“We can’t assume that no people were exposed to lead content as much as we can’t assume that everybody was.”

tweet this

You have to wonder if, like Boileau-Stockfisch, the employee who worked in room #10 at Hale Elementary School feels worried — their drinking fountain screened for 103 ppb of lead.

Or, for that matter, the occupant of room F2 at Washington Elementary School (1,500 ppb). Or room T-7 of the Jordan Center for Early Education (680 ppb), or room C of Lowell Elementary (170 ppb), or room 204 at Rhodes Junior High (130 ppb), or room P-12 at Sirrine Elementary School (410 ppb).

Since taking the leave of absence, Boileau-Stockfisch has tried to research the effects of lead on the body, and what results were like within other schools. “This affects me so personally, I’ve just been trying to figure out what is going on in the state of Arizona that we would not make it mandated for lead testing?" she said. "Why would we care that little?”

Last year’s friction with her school took a physical and emotional toll. During the turmoil over the lead results, Boileau-Stockfisch tried to make her principal and other higher-ups understand why she felt such intense concern.

Often, she’d ask them one question: “Would you want to start drinking this water for the next 18 years?”