Gerry McCue gets a kick out of describing the moment last fall when he first heard the airplanes over his house.

"I thought the city of Phoenix was being evacuated and I didn't get the memo," the 85-year-old says, opening his eyes wide for dramatic effect.

Like many residents in Phoenix's downtown historic area -- as well as those living in Laveen and certain parts of Tempe -- when Gerry and his wife, Marge, woke up on September 18, 2014, the house they had lived in since 1962 was suddenly under a major flight path out of Sky Harbor International Airport.

At the time, they had never heard of "NextGen," but that would change very quickly.

"They come in batches. You can hear it for four continuous hours -- rooooaaaar, rooooaaar, rooooaaaar," Gerry says, trying to imitate the drawn-out sound of an engine. "You hear it coming, and just as it peaks out, you hear the next one."

He likens it to Chinese water torture: "constant, chronic."

The noise interrupts their conversations and keeps them from sitting outside or inviting guests over for a BBQ. The sound makes them unconsciously tense their jaws and grit their teeth. And even worse, it has reduced the value of their home by over 30 percent -- no small dent in their life savings.

Sitting in their living room, backs to shelves lined with trinkets and framed family photographs, Gerry and Marge are the epitome of charming: Him with a trimmed white mustache and the elongated earlobes of old age; her with a delicate frame and the thick, strong fingers of an artist.

They'll happily take any visitor on a tour of their house, proudly describing the home improvements they've made in the past 53 years. They talk about how they got rid of the kitchen tile countertop Marge never felt looked clean enough, built a backyard patio with recycled bricks, and converted the unattached garage into an art studio.

Now that they're retired -- Gerry worked helping disabled people find employment, and Marge was a teacher -- they spend much of their time in that studio. He works at his drawing table by the back wall, colored pencils in hand, and she sits at her sewing machine by the window, piecing together elaborate fabric dolls. Their soundtrack is the noise of airplane engines.

Taped on the walls of the studio are dozens of Gerry's drawings, mostly of historic houses in the neighborhood: colonials, bungalows, adobes. The McCues are active members in the Phoenix Historic Neighborhoods Coalition, devoted to reviving the area's pre-blight, picturesque image. Their neighborhood really has come a long way in recent decades.

As hyperbolic as it may sound, they and others in Phoenix believe the new Sky Harbor flight paths threaten to reverse restoration efforts and waste the millions of taxpayer dollars spent on revitalization.

Phoenix has a long and special relationship with Sky Harbor. The city quite literally grew up around the airport. It's a crucial Southwestern hub and one of the country's busiest airports. But ever since flight paths were changed in September, residents' relationship with the airport, and their trust in the city's Aviation Department to manage it, has been called into question. What's playing out is both a local struggle and a national debate pitting the perks of aviation modernization against a disastrous programmatic rollout.

There's a strong grassroots effort to solve the noise problem in Phoenix, and it shows no sign of wavering. So far, the strategy has been cautious and diplomatic, but as residents become increasingly frustrated with the slow pace of change, they're getting local, state, and federal politicians involved -- with mixed results. U.S. Senator John McCain, the dean of Arizona's congressional delegation, has told residents to complain to the FAA, says Steve Dreiseszun, one of many disappointed constituents. Other leaders have responded, albeit tepidly. On February 20, U.S. Senator Jeff Flake wrote to the Federal Aviation Administration, encouraging "continued cooperation and dialogue" with Phoenix.

Some residents are happy with the current tactic, but others are pushing for more. Now the big question is whether to risk the progress made so far by suing the FAA.

People in Phoenix have been outraged ever since Sky Harbor Airport changed its flight paths in September 2014. No one from the FAA or the city's Aviation Department asked for public input, let alone announced that changes were coming. The FAA says it can't be blamed because the Aviation Department agreed to the new flight path designs, while the latter maintains it received the final plans only two weeks prior to implementation.

Because no one did a good job explaining why these changes occurred, Phoenix residents took it upon themselves to figure it out. They used social media and held private meetings to share information, and by the end of September, hundreds of locals were well versed in aviation policy and the details of NextGen.

NextGen is short for the FAA's Next Generation Air Transportation System, a massive reorganization of all air traffic control management and coordination efforts. Congress approved the program in 2003, and since then, the technology has been slowly implemented in some of the busiest airports around the country. Phoenix was the 10th city on the FAA's list, and it appears to be affected by noise more than others.

There are multiple moving parts and technologies involved in NextGen, but at its most basic level, it's about keeping pace with global aviation trends and switching from a ground-based radar tracking system to a much faster and more reliable satellite-based digital system -- think an upgrade from radio waves to GPS.

The FAA's mission is safety and efficiency in U.S. airspace, and everyone agrees NextGen advances both. Radar technology is not only slower but also becomes less accurate as the distance between an air traffic control tower and an airplane increases. The NextGen system eliminates these problems, making it possible for planes to fly more direct paths between locations. The technology also is designed to reduce arrival and departure-related delays, specifically weather-related ones, which currently account for 70 percent of delays nationwide.

The number of planes permitted to fly in any given area is constrained by both federally mandated limits on how close airplanes can be to one another and by areas of restricted airspace -- above military bases and government buildings, for instance. But by more reliably and accurately providing information about a plane's exact location, the FAA can safely reduce these buffer zones. The positive economic impacts of increased commercial aviation activities across the country should not be underestimated.

Though NextGen is a necessary federal initiative, its rollout has been a public relations disaster in many cities across the country. The most visible and controversial aspect has been flight path changes and their associated noise. For the most part, the old flight paths at Sky Harbor required planes to ascend and descend over a nine-mile stretch of the Salt River before turning or landing, which concentrated the worst noise in non-residential areas.

The new paths have pilots turning after three miles, so the aircrafts are lower to the ground and, thus, louder when they fly over residential neighborhoods. The new procedures also streamlined post-turn flight paths, meaning that planes fly one after another over the same areas.

At peak hours, they go over residential areas every two minutes.

Airplane noise can make babies cry and dogs bark. It disrupts conversation and people trying to work from home. Since the changes were implemented, Phoenix residents have reported that the noise shakes their dining room chandelier, disrupts their Internet connection, and interferes with their service dog's ability to perform. Others worry about low-level vibrations degrading the structural integrity of their historic homes over time, or the potential health impacts -- a 2012 study by Boston University linked frequent exposure to airplane noise with high blood pressure, hypertension, and sleep disorders. (A European study found similar results.)

The initial launch of NextGen was slow. Every change was meticulously researched in an effort to prevent noise-related problems. But in 2012, nine years into the program, it was so far behind schedule and over budget that Congress passed the FAA Modernization and Reform Act. The bill told the FAA to speed up things and gave the agency permission to bypass certain environmental-assessment procedures if bureaucrats thought the impact would be minimal.

This was when things first got messy.

Gerry and Marge McCue moved from Tucson to Phoenix in 1962, the same year the airport finished constructing Terminal 2. When the young couple arrived in the early 1960s, Sky Harbor was on its way to becoming a major Southwestern hub, but it wasn't there yet. It's hard to imagine now, but the airport was once located so far on the outskirts of town that it was nicknamed "the farm."

The original facility was built by a private company in 1928 and then promptly put up for sale after the stock market crashed the following year. No one wanted it, not even the city of Phoenix. Another company eventually bought the property but persuaded the city to purchase it six years later for $100,000.

Early on, the airport itself was unimpressive and looked like a warehouse. But the air traffic control tower, which was built from welded underground fuel storage tanks, could be seen from far away. Back then, Sky Harbor's biggest claim to fame was the constant stream of out-of-town elopers. Arizona was one of the few states that didn't require a waiting period to get a marriage license, so couples used to fly in, walk to the chapel a short distance from the airport, get hitched, and fly home.

When Sky Harbor got its first two-way radio system in 1937, it started attracting airlines like TWA, Southwest, and American Airlines. By 1957, it was the 11th-busiest airport in the country, and in desperate need of expansion.

Sky Harbor was servicing more than a million passengers annually by the time the McCues moved to town. Gerry, who often traveled for work, was one of them. Marge remembers buckling their four young children in the back seat of the family car and dropping him off at the airport entrance. Gerry would wave goodbye, and with a suitcase in hand, walk through the main door and board his plane.

Up until the late 1960s, the growth of downtown Phoenix largely mirrored that of Sky Harbor. Neighborhoods like F.Q. Story, Evans Churchill, and Willo developed into quaint suburbs with wide streets lined with what Gerry calls "a potpourri of architectural styles."

It was during the height of the building spree that the McCues rented their two-bedroom house on Laurel Avenue in the Fairview Place neighborhood. It was small, but they were saving up to buy a home someday.

Life in that part of Phoenix changed when the city announced its plans to construct Interstate 10.

"There was a lot of discussion about where it would go, and most of us wanted them to build it around the city," Gerry says. "When they decided to run it through downtown, we were dumbstruck."

The city tore down 1,700 homes and demolished 66 businesses to make way for the freeway. It took years for actual construction to begin, but property values dropped quickly, and people moved away.

"You've heard of white flight; I call what happened here 'fright flight,'" Gerry says.

The McCues recall an era of abandoned homes, squatters, and a spike in the crime rate. Marge remembers the way her footsteps echoed through the empty hallways of Kenilworth Elementary School after she dropped off their youngest daughter each morning. Family friends told Marge they couldn't understand why the McCues were staying in the area.

"This neighborhood will never be good again," they warned her.

But the young couple decided to stay -- in part because they loved their house, and in part because their landlord offered to sell it to them for what previously would have been way, way below market price.

The first thing that comes to Gerry's mind when he thinks about those years is an article he read in the Arizona Republic. Don Dedera wrote that I-10 "uglified the 20-mile midsection of Phoenix." He said the blight it caused resembled "a bombed-out war zone . . . [evolving] into a symbolic no-man's land."

Gerry keeps a copy of Dedera's article handy and likes to read from it when discussing the flight path changes: "Openly discussed were doubts that Phoenix ever would straighten out its transportation mess."

Yet while the downtown area deteriorated, business at the airport boomed. After spending $35 million to build a third terminal in 1974, Sky Harbor's annual traffic increased from 4.4 million travelers to 7 million. And after the 1978 Airline Deregulation Act ended federal control over the airlines, flying became an accessible form of transportation for the average person. In 1985, over 11.6 million people traveled through Sky Harbor, and in 1989, construction of Terminal 4 began.

It also was in the mid-'80s that Phoenix decided to build a tunnel for the downtown stretch of I-10, and people began talking about how to revive downtown. Community members and the city poured millions into revitalization efforts, and eventually it worked. Property values rose, young people moved in, and the area became hip again.

It is against this backdrop that the McCues and their neighbors view the flight path changes as an insult.

"All that money has been spent, all that effort to resurrect these neighborhoods after the highway went in. And now, suddenly, there's a new highway over your house! These planes are an invasion, not just an intrusion," Gerry says.

During a Phoenix City Council meeting in December, resident Don Conrad stood at the microphone.

"Remember the lessons of history here in Phoenix: that things can turn very rapidly," he said. "Think of what happened in the early '60s -- how quickly our downtown went from a vibrant area to a ghost town."

Within days of the flight path changes last fall, Sky Harbor's noise complaint hotline was inundated with phone calls. Officials at the Aviation Department tried explaining to angry callers that there was nothing the airport could do, but under the pressure of so many complaints, they eventually scheduled a public meeting to address the situation.

Had anyone anticipated that more than 400 people would show up, a different venue might have been selected, because on October 16, the two chambers of the City Council building were packed, and the overflow spilled out the front door. For those not lucky enough to be inside, a loudspeaker broadcast the two-hour meeting.

Fittingly, planes flying overhead made it impossible to hear.

The session began with a presentation from the Aviation Department, and then FAA Western-Pacific regional director Glen Martin made a brief comment promising to relay concerns to his agency.

Though the outcome of the day wasn't the immediate flight path changes most people hoped for, a respectful and constructive tone was set.

"The plan worked," says downtown Phoenix's newest aviation policy expert, Ginger Mattox, a 62-year-old former business consultant turned local activist.

Unbeknown to many, 160 people had met privately a few days earlier to strategize about preventing angry individuals from ruining the city's chance for dialogue. Local leaders like Mattox and Steve Dreiseszun -- a photographer and fellow historic preservation advocate -- are adamant about civility. "This is what separates [us] from everyone else [in Phoenix]," she says. "We're in a sweet spot and should continue down this path."

The new flight paths were the only agenda item at the December 16 City Council Policy meeting, and unlike in October, residents -- and especially a couple of council members -- didn't try to hide their frustration.

Tamie Fisher, acting director of the Aviation Department, was put on the defensive. People wanted to know why the airport wouldn't go back to the old flight paths. They asked when airport officials learned that these changes would occur, hinting that she purposely kept it a secret.

Fisher explained that before the change, only the airport's "technical experts" had consulted with the FAA about "technical plans." She said that they first received these drawings in September 2013, and that it was "at this point that the Phoenix aviation team should have inquired more about the environmental analysis" and "the FAA's plans to communicate these new procedures publicly."

Though the council members and public came down hard on Fisher, the questions they asked her proved to be a dress rehearsal for the attack they later directed at Martin, the FAA representative.

"I don't really have an excuse about why we didn't reach out to the city," he said. "I'm certainly not here to tell you we did everything right." When asked about the FAA's plan to review its mistakes, his response did not go over well: "The FAA is really not expending any resources to try and look back to figure out where we tried to communicate." By the time he clarified his statement, adding that it was because the FAA was looking forward to find solutions, it was probably too late: He was the bad guy and the target for everyone's anger.

"I guess I just don't understand what we get by waiting, hoping that maybe the process that was so flawed that we wound up here in the first place is going to produce a better result the second time around," said Vice Mayor Jim Waring. "Why wouldn't my first recourse -- rather than waiting to see how it plays out -- be to authorize our lawyers to sue? It's about the only recourse I can think of that we've got."

As the audience clapped, and Mayor Greg Stanton requested decorum, Glen Martin sunk low into his chair.

Though the FAA was not required to do a full environmental assessment before implementing NextGen, it did need authorization from two groups: the City Aviation Department's technical experts and Arizona's State Historic Preservation Society.

A year before changing the flight paths, the FAA sent a letter to the preservation society explaining that the plan would have no impact on historic areas because "the proposed action is determined not to disrupt conversation and is no louder than the background noise of a commercial area." The organization signed off on the plan but since has rescinded its support because the FAA's assertion is clearly not true.

On December 23, 2014, Phoenix City Manager Ed Zuercher formally requested that the FAA "immediately cease the use of the new flight path and utilize departure and arrival flight paths that were in effect prior to September 18, 2014."

The FAA sent a letter back saying no.

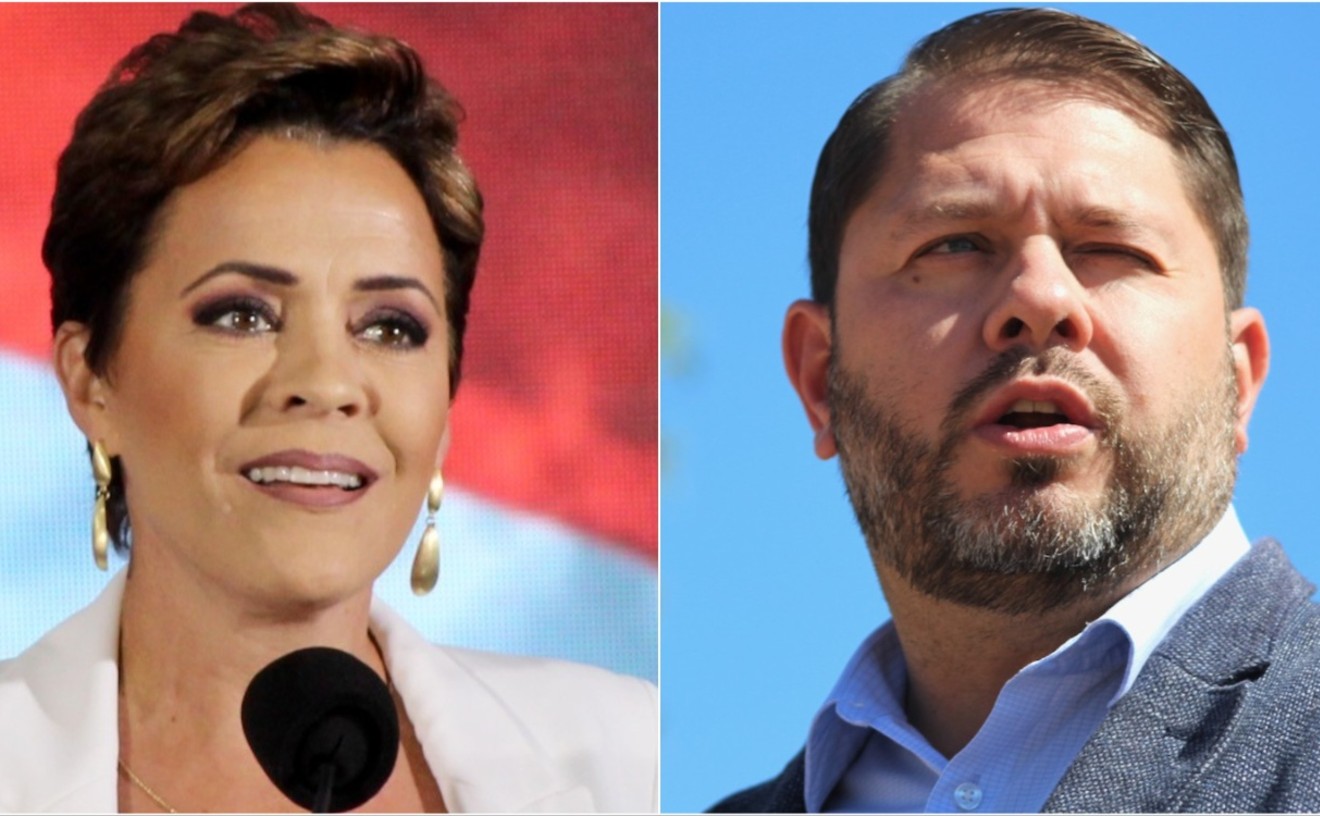

In mid-January, Mayor Stanton and Democratic Congressman Ruben Gallego met with top FAA officials in Washington, kicking off the first session of a technical working group designed to address the noise issues in Phoenix. (Former Democratic Congressman Ed Pastor was nominated to represent the city during these meetings, the third of which will take place Tuesday, March 9.)

The best way to tell how any announcement or policy change goes over with Phoenix residents is to read comments on the "Let's Make Some Noise" Facebook group page. Much of the behind-the-scenes activity and discussion takes place there.

As council members boasted about the working group, one local resident, Derk Finstad, wrote that it "smells like an FAA placebo meant to delay a certain lawsuit . . . The longer this continues, the more difficult it will be to undo. I say lawsuit first and negotiate in the meantime."

It wouldn't be the first time. In March 2014, residents of Milton, Massachusetts sued the agency after paths out of Boston's Logan Airport were changed without sufficient public notification -- a small notice was placed in a local newspaper calling for public input. The co-chairs of the BOS Fair Skies Coalition, Sheryl Fleitman and Philip Johenning, tell New Times on a conference call that they tried diplomacy first -- "we made tremendous efforts to reach out on local, state, and federal levels," Johenning says -- but realizing that they were getting nowhere, the group sued the FAA. Their case contended that the FAA used flawed methodology to measure the noise impact prior to implementation. They lost after being unable to prove the agency acted, in the words of the judge, "unreasonably."

Barbara Lichman, an attorney specializing in aviation policy and law, says that the likelihood of winning a case about NextGen-related flight path changes is very, very low. "The FAA is given total authority by Congress to control the airspace." She says she wishes she could be more optimistic but reminds anyone considering legal action that they'd be up against an agency with practically unlimited resources.

Even getting the necessary evidence for a lawsuit has proved to be a challenge. After the Aviation Department filed a very broad request under the federal Freedom of Information Act for all documents related to the flight paths earlier this year, the FAA said it would take up to six months and cost $10,000. (The FAA since has waived the fee.)

Clearly, any lawsuit will be an uphill battle, but that hasn't disheartened or dissuaded many residents and representatives.

"I think we're going to have to sue the FAA at the end of the day because I think we're just dragging this whole process out," Councilman Michael Nowakowski said at a February 25 council meeting.

Vice Mayor Waring told the room that "we're on a trip to nowhere here" and that "we're going to end up in court." Then, a community member told the room that on NextDoor.com, "the heat is on." People are ready for a lawsuit.

The city, which increasingly seems to be headed in the direction of legal action, actually got one step closer on February 17 when it filed a legal protest against the FAA demanding, among other things, a new environmental assessment. City officials are clear to point out that a legal protest is not a lawsuit.

Complicating everything, though, is the reality that the FAA probably didn't do anything illegal -- a sort of "letter of the law versus spirit of the law" situation, Ginger Mattox says.

When Congress told the FAA to expedite the process in 2012, it authorized the agency to determine whether an action would have a significant affect on the quality of the human environment. If the agency decided there would be no impact, it could file what is called a categorical exclusion and bypass further assessment. To even take the FAA to court, a plaintiff needs to prove that the FAA acted in an "arbitrary or capricious" manner.

"You go right ahead and sue," Mattox says. "You won't win."

In fact, the chances of winning are so slim that she's baffled by anyone's willingness to toss aside the progress they've made so far.

"We're now in a position where we have all partners in place, and until those avenues end, there's no reason to pursue any other path. Right now, the FAA is talking to us." She and others are looking at recourses outlined deep within the government's environmental rules to get the agency to reconsider its conclusions -- not everyone is willing to read a 400-page federal document, she says.

When it comes to the flight paths in Phoenix, every solution has a weakness. Winning a lawsuit might be impossible, but a legislative strategy could drag on for years. Even a new environmental assessment could have faults -- which, in this case, might be a machine about the size and shape of a clothing iron.

On a warm afternoon last month, Christian Valdes, a sound consultant hired by the Aviation Department, was standing in a Tempe parking lot while listening for airplanes. He could hear one approaching before he could see it -- the thundering sound getting louder and louder until a second after it passed overhead. He marked the time each one flew by, which on this particular day was about every two minutes. A few hundred feet away in a patch of grass, a small machine recorded noise-level data.

For 10 days in February, Valdes conducted noise tests at 37 locations across the Valley. Sarah Carter, planning program manager at Sky Harbor, says qualitative and anecdotal evidence about jet noise exists but the Aviation Department and the FAA need quantitative data to back it up.

A few months ago, people were optimistic about the tests. But at this point, there doesn't seem to be anyone outside the Aviation Department who has any faith in them. Some call the tests a PR sham, and others says they are a delay tactic or a complete waste of time. But everyone agrees that the way the test measures noise is problematic.

The FAA uses a metric called the Day-Night Average Sound Level (DNL), which takes the mean of all noise in a given time period, giving slightly more weight to sound produced between 10 p.m. and 7 a.m. The government considers sound below 65 decibels to have "no significant impact" -- 65 decibels, by the way, is about as loud as a major city center.

If you want to calculate long-term noise levels, DNL makes sense. But if you want to measure the impact of planes flying over your house, you need a metric that accounts for peak decibel level and frequency because a yearly average will not reflect the severity of the problem. (A second problem is that the noise we hear -- the noise captured during the tests -- is different from the low-level vibrations that can degrade building integrity over time.)

As Valdes recorded a plane flying overhead, the sound meter slowly rose from 45 decibels to 72 decibels. And this plane wasn't even the loudest one.

"I'm worried about the noise-monitoring tests. My hunch is that they're not going to be very helpful," says Simon Wheaton-Smith, a retired FAA employee who lives a few streets away from the McCues in the Encanto-Palmcroft neighborhood.

He probably understands Phoenix's situation better than most, but he's not spending much energy thinking about the noise tests. His focus is finding a solution palatable to the FAA and Phoenix, and he has plenty of ideas.

"You have to play by the FAA's rules," Wheaton-Smith says. The agency is methodical and technical, so the solution must be as well. Before the October 16 meeting, he and a few of his old work buddies spent hours studying the new flight path maps and looking for alternative solutions. What looks like a random combination of lines, numbers, and degree measurements to most of the world is a language he understands.

"I speak FAA-ese," he says, laughing.

Wheaton-Smith presented a handful of suggestions to the FAA late last year: Sky Harbor could delay the turn, shift the angle, or ascend at a slower speed. "You can find multiple solutions that work for everybody," he says.

According to the FAA, his suggestions are still under consideration.

Yet while he's busy designing technical plans, and Mattox is studying environmental policy, everyone else is anxiously waiting for March 14.

Before Ed Pastor left Congress in January, he got a rider into the federal appropriations bill that directed the FAA to give a progress report on the Phoenix situation within 90 days. If the FAA complies, which, by the way, it's not legally obligated to do, the city should hear something any day now.

Just remember, Wheaton-Smith says, change will not happen overnight. "Designing a process is a very complicated procedure."

But he, like a handful of other optimistic folks, appears to be a shrinking minority.