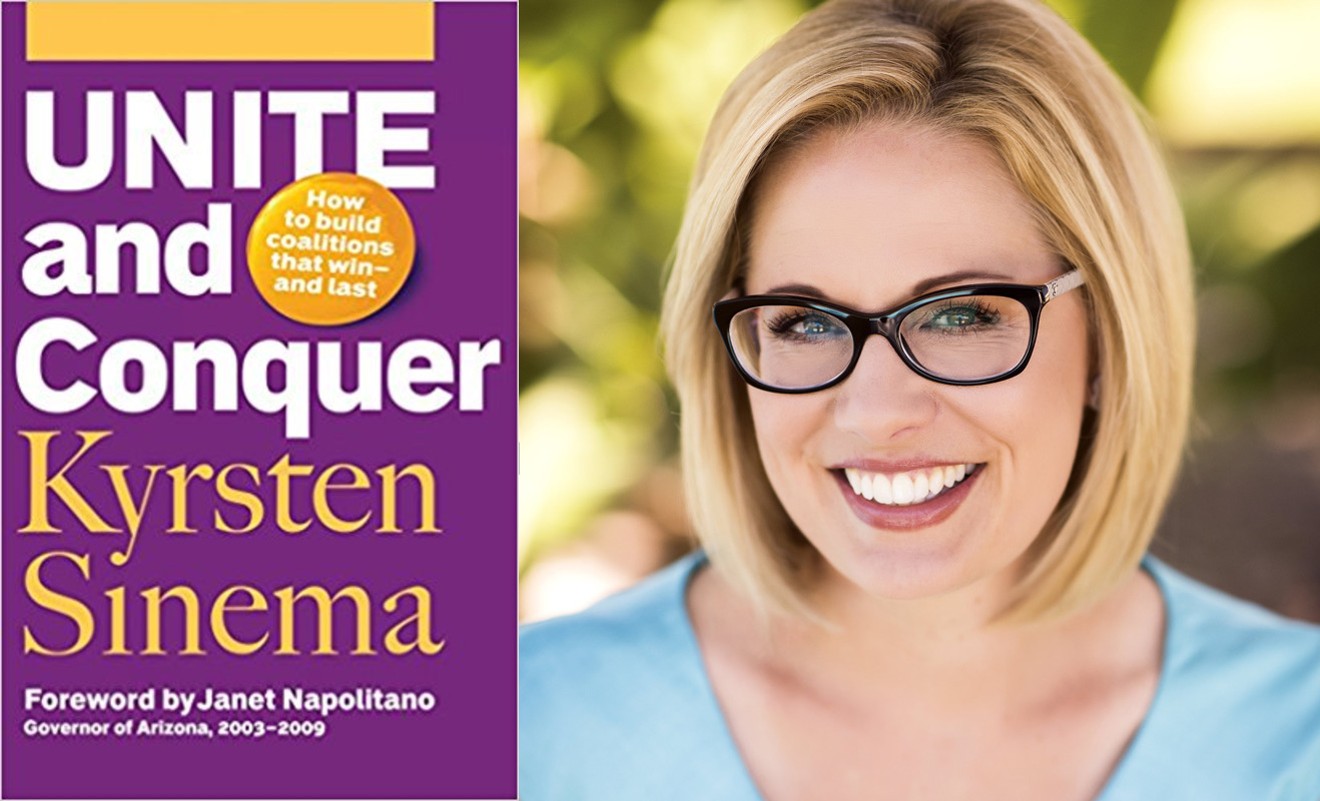

Titled Unite and Conquer: How to Build Coalitions That Win — And Last, it's a how-to manual with elements of a political memoir mixed in. You don't need to buy a used copy on Amazon — just read on and get the main highlights.

Published in 2009, while Sinema was serving in the state Legislature, the book is a quick, 170-page read. It's written in a perky and quasi-folksy tone — she describes the Minutemen, for instance, as "guys and gals who patrol the U.S. border with guns searching for immigrants crossing the border." Everything is "nifty" or happens "in a jiffy" or is "the greatest thing since sliced bread."

While these stylistic tics quickly become grating, the book provides an interesting look at how Sinema went from being an antiwar Green Party activist to a centrist Blue Dog Democrat who frequently votes with Republicans. Here, for instance, is how she describes her first session in the Legislature:

For the first several months, I was bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, coming to work every morning full of vim and vigor, ready to face off for justice—which made me rather annoying. I'd stand up four or five times a week on the floor of the house and give scathing speeches about how this bill and that bill were complete and utter travesties of justice, and the paper would capture one or two of the quotes, and then we'd vote on the offending bills and they'd pass with supermajorities. I'd get righteously indignant and head back to my office, incensed that my colleagues could not only write but actually support and vote for such horrid policies!Sinema doesn't change her political viewpoints over the course of the book, but she starts giving fewer fiery speeches and becomes friends with super-conservative legislators like Eddie Farnsworth and Andy Biggs. Despite disagreeing with Russell Pearce, the primary sponsor of SB 1070, on pretty much everything, she's able to start seeing him as a human after she learns that his favorite thing to do is to take his wife to the movies every weekend and share a popcorn and M&M's.

Meanwhile, everyone else went to lunch. In short, my first legislative session was a bust. I'd spent all my time being a crusader for justice, a patron saint for lost causes, and I'd missed out on the opportunity to form meaningful relationships with fellow members in the legislature, lobbyists, and other state actors. I hadn't gotten any of my great policies enacted into law, and I'd seen lots of stuff I didn't like become law. It was just plain sad.

"I don't mean that we should all of a sudden abandon our principles and adopt moral relativism," she writes. "I just mean that we should consider the idea that perhaps people with views different from our own come about those ideas honestly and that those ideas aren't inherently evil." [Emphasis is Sinema's.]

Ultimately, she manages to pass two pieces of legislation. One prompted the state to divest from Sudan amid the genocide taking places in Darfur, and another legalized public breastfeeding by ensuing that nursing mothers can't be charged with indecent exposure.

As anyone who's spent ten minutes at the Capitol can tell you, getting your bills passed if you're a Democrat is a near-impossible task. So how did Sinema do it? By finding ways to appeal to conservatives.

The lactation bill, she writes, had to be about "a mother's need to take care of her baby," not framed as a women's rights issue. And once she sat down and talked with Farnsworth and Biggs, she learned that Republicans were okay withholding financial support from a genocidal regime as long as the law included a provision saying that the state's pension funds didn't have to take any action that would cause them to lose money.

The other signature accomplishment that Sinema touts in the book is her success in defeating a ballot initiative that would have banned same-sex marriage. In a chapter titled "Shedding The Heavy Mantle of Victimhood," she credits her willingness to let go of identity politics for making it happen.

"You can't win something this big with two gay-rights groups, the ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union), and Planned Parenthood," she writes, explaining, "We wanted to create a situation where a voter who was conflicted about relationship recognition for gay people could vote no on Proposition 107 and feel comfortable with that vote."

The Arizona Together coalition, which she helped lead, ran a campaign that focused on how the proposed law would prohibit legal recognition of domestic partnerships, hurting straight people who live with long-term partners without getting married. Unsurprisingly, not everyone in the gay-rights community was thrilled.

"I still get angry e-mails from some members of the LGBT community," Sinema writes. "At first, this really surprised me. I mean, this was a historic victory! I would think people would send flowers — or chocolate (I really like chocolate.) But no. Turns out, a whole lot of people didn't like this campaign because they felt it didn't speak enough to the trials and tribulations of the LGBT community (which most certainly exist in Arizona). Because the campaign told the story of Al and Maxine, a straight couple who would be hurt by the passage of the initiative, a number of people accused me and the rest of the team of 'throwing the gay community under the bus.'"

It's a theme that emerges throughout the book: Activists accuse Sinema of being a sellout, and she defends herself by saying that she's just being pragmatic.

In the nine years since Unite and Conquer was published, those criticisms have only intensified.

Unfortunately, the book predates some of her more controversial decisions, such as voting to block the resettlement of Iraqi and Syrian refugees, or siding with Republicans on increasing penalties for people who re-enter the country illegally. In both cases, Sinema offered boilerplate statements to the press explaining her votes, but observers were left to wonder if she's genuinely become more conservative over the years, or if she's abandoned her previously-held principles for the sake of furthering her political career.

The book does offer one main takeaway: Kyrsten Sinema really, really cares about winning.

Reflecting on the times when she gave an impassioned floor speech about "this or that most horrible legislation" only to have the bill pass by a large margin, she concludes, "At the end of the day, all I had was that speech. Which frankly isn't the same as winning."

Is wanting to win a bad thing? The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee evidently doesn't think so.