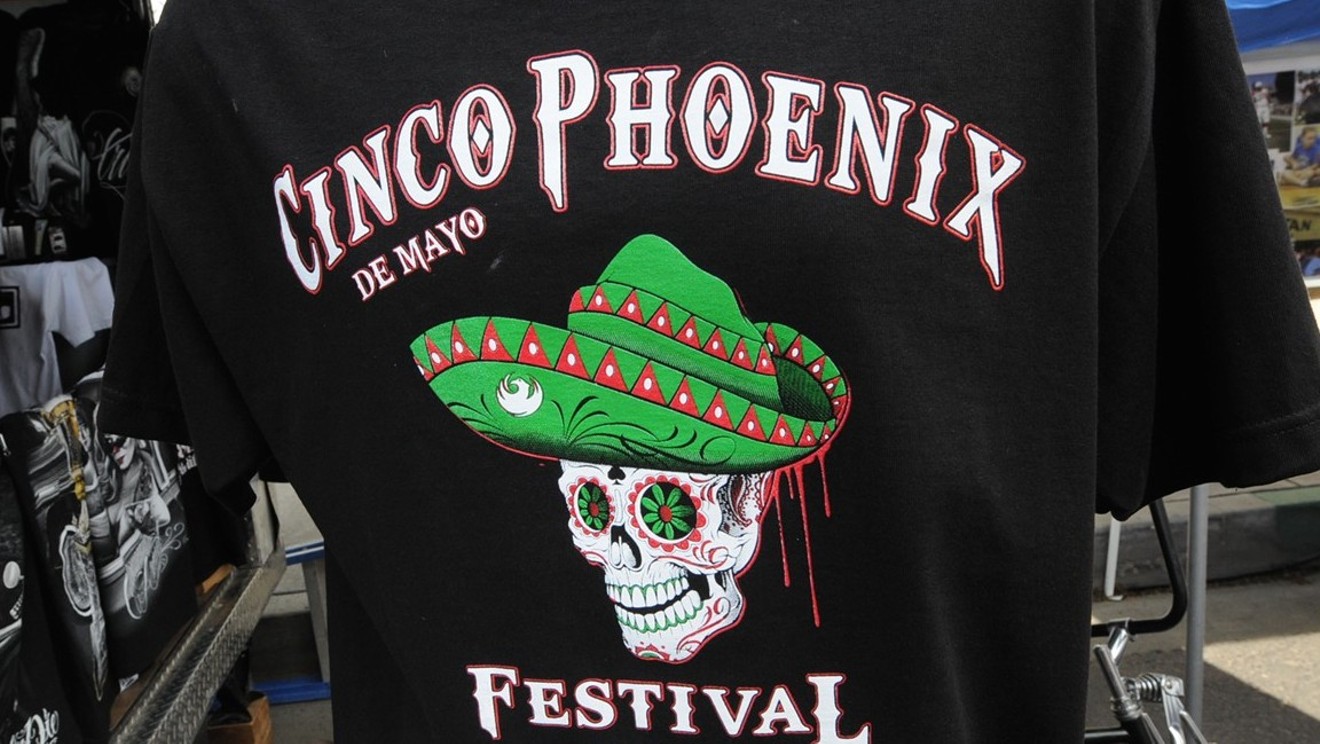

The Cinco de Mayo Phoenix Festival has been going for 25 years and is one of the more tasteful celebrations of the holiday

Benjamin Leatherman

If you Google “Cinco de Mayo,” as I just did, you’ll find the internet flush with articles like “What Is Cinco de Mayo?” (Good Housekeeping), or “Why Do We Celebrate Cinco de Mayo?” (USA Today), or “FACT CHECK: What is Cinco de Mayo?” (Snopes).

If you didn’t know any better, you’d think that Cinco de Mayo is some mysterious phenomenon or secret cult ritual. It’s not, of course. The date marks an event that took place more than a century ago: the Battle of Puebla, on May 5, 1862, when Mexico’s impoverished army defeated Napoleon III’s vastly better-equipped French troops near the city of Puebla.

In Mexico, this David-versus-Goliath episode is celebrated mostly only in Puebla, where it’s commemorated with family-friendly activities like historical re-enactments and a parade. In the U.S., it’s been commemorated in some form or another since 1863, evolving into a distinctly Mexican-American civic holiday that’s often recognized with parades, pageantry, and open-air concerts (shout-out to the Cinco de Mayo Phoenix Festival Committee for programming a kick-ass concert series in downtown Phoenix for 25 years now).

But for millions of Americans, Cinco de Mayo is best known as a late-spring drinking holiday. On its highly scientific ranking of “Top 10 Drunkest Holidays,” Time magazine places it at number four, right behind Thanksgiving Eve, St. Patrick’s Day, and New Year’s Eve.

For all its mainstream popularity and cross-over appeal (tacos and tequila make for deeply compelling party favors), Cinco de Mayo is the least-understood, and most problematic, of the American drinking holidays.

The holiday is perennially misunderstood; after all these years, it’s still widely confused for Mexican Independence Day. Writing about Cinco de Mayo in any kind of thoughtful capacity inevitably makes you sound like a beleaguered history teacher, doomed to trot out the same dusty set of facts every year (“Actually, Mexican Independence Day is on El Dieciséis de Septiembre, or September 16”). It turns you into something of a side-eyeing, sometimes finger-wagging nag, pleading to anybody who will listen about why it’s wrong to indulge in ethnic stereotypes and “dress up” as a Mexican for Cinco de Mayo. As if basic, everyday decency demands a full, footnoted explanation.

Cinco de Mayo is famous for routinely inspiring a particularly cartoony, smug, aw-shucks strain of racism: the college coeds in dollar-store sombreros and itchy fake mustaches (because, ostensibly, Mexicans are kind of funny and goofy, and sometimes it’s fun to dress up like them).Cinco de Mayo is famous for routinely inspiring a particularly cartoony, smug, aw-shucks strain of racism: the college coeds in dollar-store sombreros and itchy fake mustaches...

tweet this

The Kappa Sigma bros in brown face who get off on organizing “politically incorrect” Mexican-themed keggers. The politicians tweeting charmlessly about drinking jars full of hot sauce and watching old Speedy Gonzales cartoons in honor of Cinco de Mayo (thanks for that one, Mike Huckabee). And that now-iconic Cinco de Mayo Twitterpic courtesy of Donald Trump, a devilish wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing grin pasted on his face, giving the thumbs-up next to a mystery meat-laden taco salad.

“I love Hispanics!” tweeted the man who launched his presidential campaign on the premise that Mexican immigrants are largely rapists and drug-runners.

Cinco de Mayo, when it’s “celebrated” by people whose interest in Mexican history and culture is as deep as a puddle, is a day of empty gestures and racial caricature. It’s a day that highlights the profound irreverence that still characterizes much of U.S.-Mexico relations. In a sense, Cinco de Mayo reveals who and what we are — and very often we are revealed as not very enlightened or culturally competent human beings.

Last year, I argued that Cinco de Mayo is kind of a bullshit holiday, because it’s been thoroughly appropriated by the Big Cerveza conglomerates, who have helped turn a quiet civic holiday into what feels like one big Corona-soaked wet T-shirt contest. I argued that it’s fine to celebrate Cinco de Mayo. I stand by that. I love a good taco and tequila party as much as anybody, and I’m grateful for any excuse to indulge in these things in good company (the smart angle, though, is to use Cinco de Mayo as an excuse to eat mole poblano, tinga de pollo, or other regional delicacies from Puebla, the site of the battle and Mexico’s famous gastronomic center).“I love Hispanics!” tweeted the man who launched his presidential campaign on the premise that Mexican immigrants are largely rapists and drug-runners.

tweet this

Cinco de Mayo, for better or worse, means different things to different people. For you, it might imply a specific sequence of small, profane rituals: drowning yourself in tacos and tequila shots, then getting sick in the back seat of your Uber driver’s Honda Civic. For me, Cinco de Mayo is a little more complicated. Cinco de Mayo is a fun holiday, sure. But it’s also a small reminder of stubborn American ignorance, and the ways racism is sometimes dispensed playfully, with a smile.