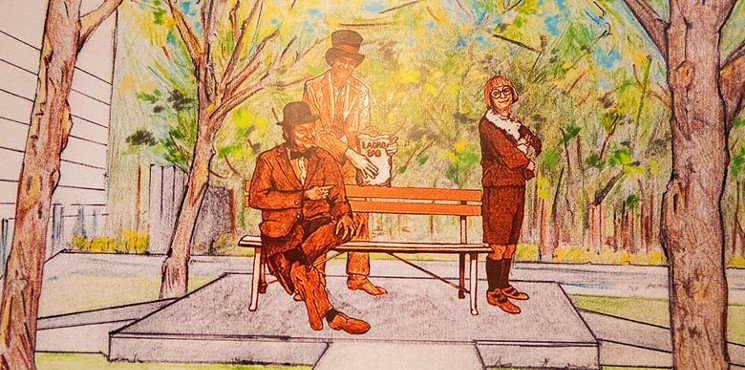

It’s a warm July afternoon in Phoenix. Mr. Grudgmeyer is seated on a park bench enjoying his afternoon newspaper. A man — or perhaps he’s a giant boy — plops down beside Grudgmeyer, who might roll his eyes if they weren’t painted onto his heavy black spectacles. The man-child is Ladmo, a top-hatted television goofball beloved by all Phoenicians — all but Grudgmeyer, an old crank who knows Ladmo as a pest and a troublemaker.

As violins play, this idyll turns nasty. Ladmo annoys the old guy by noisily opening a sack of potato chips; Grudgmeyer smacks him with a rolled-up Phoenix Gazette. Ladmo gets even by making even more noise, and Grudgmeyer sits on Ladmo’s bag of chips. Very shortly, Ladmo is crying, and Grudgmeyer is looking smug.

If this were real life instead of one of a half-million or so comedy sketches from The Wallace and Ladmo Show, the famed kiddie program that aired on then-independent KPHO from 1954 to 1989, Chris Williams would be the Ladmo in that story.

“And Pierre O’Rourke is my Grudgmeyer,” Williams insists. “You wouldn’t believe what I’ve had to go through to keep the show alive, and what Pierre has been doing to try to keep me from it.”

Williams has devoted much of his adult life to burnishing the memory of Wallace and Ladmo. When he isn’t ministering to the more than 34,000 members of the Official Wallace and Ladmo Fan Club he founded 18 years ago, Williams is busy reliving a page from the show’s script: He’s a grown man, playing a hapless boy who’s brawling with a grouchy grown-up.

Over the past couple of years, Williams and O’Rourke have been in and out of courtrooms, where they’ve spent hours accusing one another of everything from cyberstalking to death threats to glaring at one another on the witness stand.

Williams says O’Rourke wants to hog all the Ladmo glory; O’Rourke, the former CEO of the Wallace and Ladmo Foundation, claims he’s just trying to protect himself from Williams’ unhinged attentions, which have taken the form of years’ worth of carefully worded Facebook taunts and, O’Rourke claims, threats to his well-being. Most everyone else thinks the squabble is proof of some kind of craziness — either Williams’, or O’Rourke’s, or both.

No matter who’s nuts, much of this story has played out like a deranged Wallace and Ladmo skit. In an era when most kid shows featured sweet-natured clowns gabbing with sock puppets, Wallace and Ladmo took a left turn. Rather than a child-friendly break from cynicism and irony, Wallace and company thrived on those things. The show debuted in 1954 as It’s Wallace?, a kicky hybrid of Howdy Doody and Ernie Kovacs that goofed on children’s programming. Bill Thompson wrote and directed and starred as Wallace (and occasionally Mr. Grudgmeyer); recent ASU grad Ladimir Kwiatkowski was Ladmo, a doofy sidekick in the tall, lanky body of an adult. Former TV weatherman Pat McMahon played everyone else: Boffo, a dour, perhaps drunken clown; Captain Super, a self-obsessed superhero; Aunt Maud, a horny, mean-spirited biddy; and a host of others.

Most of the time McMahon was Gerald, a bratty kid who hated other children, especially Ladmo. The skits wedged between Mighty Mouse and Roger Ramjet cartoons often lampooned issues of the day, but the show was centered on the ongoing bitch fight between Ladmo and Gerald.

In one sketch, Gerald wants to recite Eugene Field’s “The Sugar Plum Field.” “If I don’t get to recite my poem,” Gerald whines, “I will walk out and I may never come back. What do you say to that?” Wallace replies, “No poem!” and Gerald marches off. Later, he returns. “I was standing out there waiting for him to leave,” he says, pointing to Ladmo.

The program has become a touchstone for locals; watching it is the one thing we all have in common. “This was a monumental show,” says Williams, who’s known, even to people who hate him, as the world’s biggest Wallace and Ladmo fan. “It won nine Emmys. It was on the air for 36 years with the same cast, which has never been done before or since.”

That cast has been memorialized like mad since the show went off the air in 1989: in a mural on the side of the downtown TV studio they once worked out of; a half-dozen different books; a permanent exhibition at the Arizona Heritage Center; a pair of stage plays by former Wallace and Ladmo writer Ben Tyler; a DVD series marketed by Ladmo historian Steve Hoza, whose name comes up often — and not always kindly — in Ladmo circles. Kwiatkowski has had a pistachio tree in Kearny, Arizona, named for him, as well as a public park, a stage at the state fairgrounds, and a chapter of the Boys and Girls Club of America.

Fans of the show are thrilled that the memory of their childhood heroes will be kept alive with a bronze statue by artist Neil Logan, commissioned by the city to be installed at the Phoenix Zoo this fall. (Williams, who always refers to Thompson by his character name, isn’t impressed by news of the long-awaited statue. “Wallace would have said, ‘Give the money to the kids.’ Ladmo himself said, ‘I don’t want a statue; pigeons shit on statues.’”)

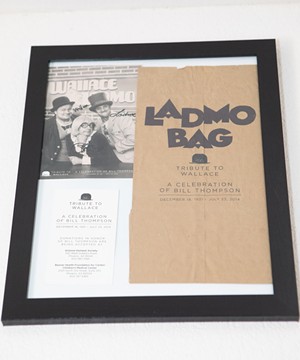

Kwiatkowski died in 1994, Thompson in 2014. But like so much of our favorite childhood detritus, these men live on in a corner of the internet, wearing silly costumes, throwing pies, and smashing straw hats in clip after YouTube clip. On Facebook pages and fansites, locals rhapsodize about Marshall Good (a milquetoast lawman played by McMahon) or humpy Sergeant Harry Florian (the police officer who talked safety issues and usually got hit on by Aunt Maud). This comic TV time capsule — let’s call it Ladmoland — is lousy with stories from fans about how they finally scored their very own Ladmo bag, a brown paper grocery sack full of Twinkies and plastic toys given out to kids who visited the show.

“If you happen to have your Ladmo bag from 1972,” McMahon advises, “here’s some good news: Those Twinkies are still edible.”

All these years later, McMahon, who’s gone on to host television and radio talk shows, is still stopped by strangers who want to talk about a sketch he did a half-century ago, a song he sang onstage at Encanto Kiddieland while dressed as a biker, or to complain that they never got a Ladmo bag.

“I can’t believe we’re still talking about this show,” says McMahon in the mellow radio voice recognized by most Arizonans. “Or that if you want to watch Wal or Lad or me, you can visit the internet, and there we are.”

Or, if you’re Chris Williams, you can visit the internet and relentlessly hassle Pierre O’Rourke.

“Chris can be difficult, let’s just say,” sighs Debi Davis. She’s seated in the living room of her west Valley home, which she’s transformed into a cozy shrine to her all-time favorite TV program. The walls of Davis’s ersatz Wallace and Ladmo museum are hung salon-style with framed photographs and souvenirs from the show: a pre-Telepromter script written in Thompson’s hand; several autographed Ladmo bags; an ancient coupon for a free Icy Parfait at the Ladmo Drive-In. A glass case displays her super-rare 7-11 Slurpee cups printed with images of Captain Super and Aunt Maud.

Davis once considered herself Williams’ best friend. She stood by him for as long as she could. “After a while, I started to get scared he was going to come after me,” muses Davis, who has an image of Ladmo’s top hat and Wallace’s signature derby tattooed above her right breast. “I watched Chris hassling all these other people, and I thought, This is just a kids’ show. I need to get away from this guy.”

By the time Williams received O’Rourke’s first injunction against aggravated harassment, Davis had stopped speaking to Williams. Most of his other Ladmoland friends quickly followed suit. O’Rourke says Williams defied the injunction, which lists O’Rourke’s dog, Gibbs O’Rourke, as a “protected person,” and refers to Williams as a “crazed fan of [the] Wallace and Ladmo TV show.”

A second injunction followed; attached were 10 police complaints filed by O’Rourke, each with as many as 50 pieces of evidence. O’Rourke contends that Williams defied the first injunction nearly 300 times in a single year, which would have meant almost daily online pissiness from Williams. The second injunction accused Williams of workplace harassment and general physical threats.

For a long time, Davis believes, Williams’ heart was in the right place. “He was all about preserving the memory of the show. But then after the stuff with Pierre started, Chris just went off the deep end, and most of us just took off.”

Williams recalls meeting O’Rourke about five years ago at a fundraising party. “He didn’t seem interested in talking to me,” Williams says. “He was more into being photographed with the celebrities who were there. He seemed a little oily to me.”

Everything was rosy in Ladmoland, Williams says, until O’Rourke was named CEO of the Wallace and Ladmo Foundation, launched in 2015 to fund the bronze statue and create arts scholarships for kids.

“Immediately, there were accusations of copyright violations,” Williams remembers. “All of a sudden they’re talking about whether I had permission to have a fan club. The fan club Facebook page was reported repeatedly. It was a mess.”

“Thank God this kind of fanaticism is rare because it’s disturbing. I’m glad I don’t have any contact with it other than hearing about it secondhand.” – Pat McMahon

tweet this

O’Rourke wanted to use Williams’ fan club to promote the foundation, but Williams was hesitant.

“They’ve been talking about giving money to kids since the beginning, but they haven’t given a dime,” Williams says. “They’ve been talking about building a statue for years, and where’s the statue? If you’re not a nonprofit 501c3 charity, I’m not going to help you out.” (In fact, the foundation operates under the Arizona Community Foundation, which oversees charities and carries a 501c3. Foundation vice president Michael Lechter confirms that, as yet, no scholarships have been given to local children.)

Outside of a courtroom, O’Rourke doesn’t like to talk about Chris Williams, whom he’ll only refer to as “CW.” Forced to discuss Williams’ crummy behavior and relentless cyberstalking, O’Rourke will only do so at his attorney’s office, where he keeps a colossal three-ring binder filled with proof of Williams’ rotten conduct.

O’Rourke moved here from Chicago in 1966. “I was a skinny little kid with Barry Goldwater glasses. The other kids picked on me. My mother, a former Marine, taught me to fight.”

But it was Wallace and Ladmo who taught him to survive. He watched the show with his uncle, picking up on the cast’s mordant comedy. “I developed a strange wit from watching the show,” says O’Rourke, a stately, 65-year-old grandfather. “The kids decided it was better to let me entertain them than to beat me up.”

O’Rourke grew up to be a forest firefighter, and later ran a fundraising company. He met and befriended the McMahons and Ladmo’s widow, and was later recruited by the McMahons as CEO of the Wallace and Ladmo Foundation.

When Thompson died, Williams called O’Rourke. “He said, ‘Wallace made me promise I would dress as the Grim Reaper and follow Pat around the funeral,” recalls O’Rourke, who concludes every story by mentioning that proof of its veracity has been “turned over to the police.” (Both Williams and McMahon, in a 2014 article published in Phoenix Magazine, report that it wasn’t Williams, but another Ladmo fan who attempted the Grim Reaper stunt.)

“The Foundation started getting calls from people who were being bullied by CW for posting Wallace and Ladmo photos on their Facebook pages,” says O’Rourke, nervously drumming his fingers on his binder of evidence. There were rumors that Williams had proposed a boxing match between himself and foundation board member Ted Thompson. Word was that some of Williams’ Ladmo posts were unseemly. Someone from the Foundation board asked O’Rourke to explain to Williams that he didn’t in fact own the photographs nor have the right to keep others from using them.

“He always claimed he had a written agreement with Wallace, which no one has ever seen,” O’Rourke says. When Williams got the foundation’s crowdfunding page shut down by claiming he owned the images used on it, McMahon sent Williams a politely worded, certified letter asking if they couldn’t work together. Williams, O’Rourke claims, refused the letter; Williams says he never received it.

Williams eventually agreed to meet with the McMahons and O’Rourke to talk about playing nice. Williams’ then-friend Marcus Peagler, who owns an Old West amusement park in Cave Creek called Frontier Town, was asked to moderate.

“I ordered a dozen cookies,” Peagler recalls, “and I told Chris, ‘Every time you open your mouth I’m gonna shove a cookie into it.’ He sat there silently.”

“They were asking him to get rid of his fake Facebook accounts, to stop bullying people at the fan club, stop telling people he owned Wallace and Ladmo, that kind of thing,” remembers Davis, who was also at the meeting. “They said if he stopped all that, they would make him an official part of everything.”

The foundation submitted a list of eight firm but polite demands, O’Rourke says. “And the carrot we were offering to CW was, if you honor those eight things, in six months to a year, we’ll consider making you the honorary Wallace and Ladmo historian, and we’ll make the fan club official. But you’ve got to stop attacking the foundation, you’ve got to quit coming up with new stories about your friendship with Wallace, all of that.”

Williams agreed to everything. But within weeks, O’Rourke says, Williams defaulted on his promise to be a Ladmoland team player.

“All Chris had to do was not poke the bear for six months,” Peagler groans. “But six months was too long. He didn’t want to wait. After about four months, he started telling me, ‘I don’t think I can do this, I think I’m gonna have to poke the bear.’ Chris couldn’t help himself, he just had to.”

“The foundation wanted to keep me quiet,” Williams reasons. “They said they were going to make me the historian, but every time I asked Pierre about it he said we’d never had that meeting, that he’d never made those promises. After that, I was done. I broke it off with the foundation.”

And returned to hassling O’Rourke on social media.

It’s easy to paint Williams and O’Rourke as feuding man-babies, duking it out over a children’s show they loved as kids. But there’s likely more to it than that, according to Karen Kolbe, LPC, a Scottsdale counselor in private practice. It might, she believes, be cathexis. Which sounds like a Wallace and Ladmo character McMahon might have once played, maybe an extraterrestrial with a lisp and a thing for designer handbags, but cathexis is actually a psychological fixation that can transform simple nostalgia into something more sinister.

“It’s a psychological construct where you imbue things or places or people with psychic or emotional energy,” says Kolbe, who used to hang out with McMahon’s kids back in the 1970s. “You remember something that was awesome, like your first car, which represented freedom, your carefree teenage years, your first girlfriend.”

But cars wear out and get sold, Kolbe says. Girlfriends move on; people grow up into more stressful adult lives.

“A normal response would be to shift the energy you put into loving your car into liking something new when you no longer own that car,” she explains. “But sometimes people fixate on the thing that represents a happy time in their lives, and they’re unwilling to transfer that energy to new things or experiences. That can lead to someone obsessing over a TV show, and the people around them might be saying, ‘That was a kids’ show that’s been gone for 30 years; why are you still talking about it every day?’”

McMahon doesn’t get it. “Thank God this kind of fanaticism is rare,” the affable 85-year-old broadcast star says, “because it’s disturbing. I’m glad I don’t have any contact with it other than hearing about it secondhand.”

But Wallace and Ladmo was more than just a TV show for Williams. “That show kept me from killing myself a few times,” he explains. “It started out as something my mom used to keep me out of her hair — she’d plop me down in front of Wallace and Ladmo. Pretty quickly, Wallace became my hero. And then I grew up and I got to be his friend as an adult.”

Everything was rosy in Ladmoland, Williams says, until O’Rourke was named CEO of the Wallace and Ladmo Foundation, launched in 2015 to fund the bronze statue and create arts scholarships for kids.

tweet this

This friendship meant more than anything else in his life, Williams says on a recent Saturday afternoon. He’s seated on the patio of the Sunnyslope restaurant where he works as a chef. His signature Ladmo T-shirt — printed, like the one worn by Kwiatkowski on the show, with a wide, brightly colored neck tie — hangs on him.

There are dark circles under his eyes. “I’ve had health issues because of all this stuff with Pierre,” Williams admits. “I’ve lost a lot of weight, and it’s hard to sleep when someone’s outside your apartment, going through your trash.”

Like O’Rourke, Williams, who’s 56, was bullied as a kid. He doesn’t like bullies. “I am being bullied by Pierre O’Rourke and the foundation,” he believes. “Wallace taught me not to back down to bullies.”

Not backing down meant mocking O’Rourke on Facebook. “After the foundation refused to deliver on their promises, I took a page out of Bill’s comedy book,” Williams says. “I took it to the extreme: Let’s see how far this will go. I kept poking Pierre on Facebook, never naming him. I called him names like Writer Boy or CEOschmo.”

Williams’ Wallace-inspired antics included posting not-so-subtle social media memes aimed at O’Rourke.

“Remember I’m a chef, so I have a reason to always carry a knife,” read one Facebook post. In another, Smokey the Bear cautions, “Remember, only you can help me bury the body.”

Williams launched a 16-installment essay series called “The CEO and Me,” in which he shared court injunctions and courtroom recaps. When Wallace fans complained, Williams posted a new message on his own Facebook page: “Why can’t you people appreciate how much work I put into NOT being a serial killer?”

O’Rourke wasn’t amused. “I had the police out to my house 11 times,” he says, pointing to his three-ring binder of evidence. “Never did they leave with less than 20 pieces of evidence, mostly screenshots CW had posted.”

Asked to explain his pestering, Williams shrugs. “I never did it on the fan club page.” He pauses. “Well, not until Pierre started throwing harassment charges at me.”

When word came that Williams planned to disrupt a roast of McMahon at a comedy club last year, the foundation acquired an injunction barring Williams from attending the event. While he was at it, O’Rourke tossed in a kitchen sink of infractions, including Williams’ supposed copyright infringements, his unsanctioned GoFundMe account, and threats against O’Rourke, his dog, the McMahons, and their pooch.

“My plan was to give Pat McMahon some footage I’d found from the unreleased Orson Welles movie Pat was in,” Williams huffs about the comedy roast. “I may have mentioned on Facebook that the side benefit of being at the roast was to really annoy Pierre. But that’s what I do. I am the hardest-working troublemaker in town.”

Williams lost his courtroom battle against that first injunction, and the judge allowed the no-contact order to stand. The battle for king of the Wallace and Ladmo hill was on.

“And then Pierre talked for two and a half hours. They had to ask for a continuance because he had so much evidence against me. ... We were there so long I was going into a diabetic coma.” – Chris Williams

tweet this

The second injunction, filed by O’Rourke in April 2017, accused Williams of workplace harassment. At the eventual injunction hearing, Williams spoke for 15 minutes about First Amendment rights and his desire to keep the memory of Wallace and Ladmo alive for their fans.

“And then Pierre talked for two and a half hours,” Williams laughs. “They had to ask for a continuance because he had so much evidence against me. He just talked and talked, and the judge let him. We were there so long I was going into a diabetic coma.”

A YouTube video of the hearing clocks in at just under eight hours. Low points include Commissioner Brian Rees asking O’Rourke to explain his prior sentence for mail fraud.

“The charges against me were for forgery and owning forging apparatus,” he replies.

O’Rourke’s attorney also asks the judge to make Williams stop “glowering and making facial expressions” at O’Rourke. At one point, Rees appears to have fallen asleep while O’Rourke is presenting evidence.

Everyone is wide awake when Peagler testifies. “He said that CW had told him he didn’t want to be a cook the rest of his life, and was thinking about committing manslaughter against me,” O’Rourke says. “Then the county could take care of him the rest of his life.”

“Eight hours is a long time to talk without proving anything,” Williams says with a snort.

Apparently Rees agreed, and quashed the injunction, telling O’Rourke he’d failed to prove his case.

O’Rourke retaliated with an amended version of the first injunction, which Williams never saw. He spent weeks dodging a process server, Keystone Cops style, then boasting about his victories on Facebook. “Let’s play dodge the process server!” read one. In another, he taunted O’Rourke with “Hey Writer Boy! Your process server sucks! Missed me missed me … now you got to kiss me!”

Williams claims the posts were educational. “I’m a teacher,” he explains. “I want people to know what their rights are. You don’t have to talk to the police. Process servers are breaking the law when they come onto your property. Of course I’m going to post about that!”

He believed the amended injunction wasn’t valid because it hadn’t been served. But while checking the status of the original injunction on the Superior Court website, he discovered an arrest warrant in his name. On Monday, April 24, Williams turned himself in.

“I’m completely innocent,” he told Ladmo fans the Saturday before. “I’ll plead not guilty, they’ll give me a hearing date, and send me home.”

In fact, police arrested Williams and tossed him into the pokey. In his mug shot, Williams is wearing a Ladmo T-shirt.

“I spent 15 hours in the Fourth Avenue jail,” he says. “I had to go through the humiliation of mug shots and fingerprinting. I couldn’t eat the food they served because I’m diabetic. It was pretty much a nightmare.”

On May 14, the criminal charges against Williams were dismissed. Williams had not, the judge decided, broken any laws with his cryptic taunts aimed at O’Rourke, because none named O’Rourke specifically.

“This is the real challenge when you’re talking about cyber-harassment,” says Ruth Carter, a Phoenix-based internet attorney. “You have to be able to prove that the person doing the posting is talking about you. If they don’t name you, there have to be enough good, solid inferences to the victim to make your case. The law only governs what can be proven.”

When cyberstalking cases make it to court, Carter says, they’re an uphill battle.

“You can win a cyberstalking lawsuit, but if the person who lost doesn’t have any money, you’ll never collect damages. You have to ask yourself how much you want to invest in this battle. It could be years of fighting. Mentally, emotionally, and financially draining years.”

Peagler has his own ideas about why Williams prevailed in court. “I think the judge thought the whole thing was ridiculous,” he says. “For the third time, he’s got these grown men fighting over a children’s show that’s been off the air for 30 years. He just seemed embarrassed.”

If Ladmoland were a real place, it would be a place built on suspicion, a doofy Denmark teeming with rot. Its foundation might be made of leery skepticism, its countryside landmarked with towering heaps of doubt and mistrust, its citizens consumed with eye rolling over whispered gossip. Their favorite topic of discussion would be not which season of Wallace and Ladmo was the best one, or which clown — Boffo or Ozob — was the funniest. Ladmoland denizens would likely be preoccupied by who has the right to do what with the likeness of their town’s namesake.

The consensus seems to be “No one does.”

“Has anyone seen that document giving the Wallace cast permission to use their likenesses?” Marcus Peagler asks about a letter McMahon says he, Thompson, and Lad received from a KPHO attorney in 1989.

“Steve Hoza’s agreement with Bill Thompson is written in pencil on a scrap of torn notebook paper,” O’Rourke sneers. “And Bill didn’t even sign his own name. He signed ‘Wallace.’”

“It’s written on a cocktail napkin,” Peagler claims. “Hoza used to always promise to show it to me, but then he never would.”

Hoza’s name comes up a lot in Ladmoland. People like to talk about how Hoza, the former curator of the Wallace and Ladmo museum at the Arizona Heritage Center, took a bunch of props and scripts and costumes from the museum archive when he abruptly left his job there.

Not so, says Bill Thompson’s son David. “Steve was a friend of my dad’s. My dad gave him all that stuff. I saw him give Steve hats, scripts, props. The stuff people like to claim was taken out of the museum was stuff that belonged to Steve. So he took his own stuff with him when he left the museum.”

A former employee who won’t give her name says, “Steve did not get fired for stealing. The story goes that he was collecting against us, and if that’s true, that’s against museum rules. Steve collected World War II things and Ladmo things, and those are two of our main collections.”

Hoza says he resigned from the center 12 years ago, when he got a better job. He continues to sell Wallace and Ladmo DVDs, and donates the money to various Ladmo-sanctioned charities.

“We have more Wallace and Ladmo stuff than we know what to do with,” she chirps when asked if Hoza ran off with everything. The new exhibition, Downs promises, will re-create the TV program’s original set.

“I saw the deal my dad made with Steve,” Dave Thompson says. “It was all written out on paper. I don’t know if he did the same with Chris, because I never saw that. But the spirit of the deal was the same: Sure, you can have a fan club! The show belongs to the kids! But Chris has a sense of ownership to the photos and the bits my dad wrote and these guys performed. It’s a psychological thing. He’s been doing it a long time and he has nothing else. He’s saying, ‘No, that’s my stuff.’ I’ve seen him attack a lady for reposting a picture of my dad. Dude, that’s not your picture.”

Williams swears he has permission to duplicate images from the show so long as he doesn’t profit in any way. That permission, he claims, came from the late Bill Thompson himself.

Williams chokes up when he recalls the occasion. “It was October 13, 2013,” he says, his eyes welling. “I was over at Wallace’s house, and he said to me, ‘I’m going to let you be the official fan club. I’m also going to let you give out official Ladmo bags.’ I could feel my heart constricting. Here I was a nobody, and here is this man who is giving me the ability to give out the most coveted Arizona thing that ever was.”

He had a box of business cards printed with a photo of a Ladmo bag on one side. On the other side are the words “Sorry it took so long.”

“That’s a two-dimensional Ladmo bag,” he explains. “I hand those out to anyone who remembers the show.”

Williams’ eyes narrow. “The foundation even tried to take that away from me.”

A handshake agreement like the one Williams says he had with Thompson could be considered binding, according to Tom Galvani, a Phoenix-based patent attorney. “But it’s not a lot to hang your hat on,” says Galvani, who didn’t grow up in Phoenix and has never heard of Ladmo. “An implicit agreement is pretty tenuous, really.”

With or without permissions, being in charge of all this Ladmo stuff is exhausting, Williams says. And expensive. Fans send him VCR tapes of the show, and Williams has to digitize them, then upload them to his fan site before storing it. He has a GoFundMe account to defray cost of preserving the show, but lately he hasn’t had time for all that.

He’s consumed with the battle of Ladmoland. In June, he filed harassment and stalking charges against O’Rourke; a few days later, he was back in court to address the misdemeanor charges in O’Rourke’s case against him. The week before, he sent a 19-page letter to Pat McMahon, explaining his devotion to the show and requesting a personal phone call from McMahon. McMahon replied with a polite email that sidestepped the feud between Williams and O’Rourke.

“He says I’ve been going through his trash,” O’Rourke moans about Williams. “That I’m holding the Wallace and Ladmo statue for ransom. That I’m calling CVS to find out what meds he’s on. I don’t care what meds he’s on. I wish he’d take them, though.”

“They were outside my apartment,” Williams says of O’Rourke’s henchmen. “And hiding behind Walgreens. They tried to follow me to work.”

O’Rourke shakes his head at this story. “CW travels by bus. How do you trail someone on a bus?”

O’Rourke has resigned from the Wallace and Ladmo Foundation. “Half of my time was spent putting out brush fires set by CW,” he says. “I hadn’t had a day off in three years. I wanted to see my grandson. I wanted to return to my writing career. I wanted to get back to my life.”"I’m living rent-free in Pierre O’Rourke’s head, and I’m trashing the place.” – Chris Williams

tweet this

For Williams, the Ladmoland battle is his life. “It’s taken its toll on me,” he admits. “But it’s also been funny as hell. I’m living rent-free in Pierre O’Rourke’s head, and I’m trashing the place.”

But if he were alive, would Wallace approve of all this squabbling and spotlight-grabbing? Would Ladmo?

O’Rourke won’t answer. Williams just shrugs. “All I know is this,” he says. “I made a promise to Wallace to keep his show alive. And nothing is going to stop me from keeping that promise.”

Williams will be back in court at the end of this month to address the misdemeanor charges, which claim Williams interfered with a judicial order. He believes it’s an open and shut case, as the order demanded he have no contact with O’Rourke.

“And I am very happy to say that I haven’t seen Pierre O’Rourke in years,” says Williams with a chuckle. He’s looking forward to this new day in court, because it will give him an opportunity to demonstrate how O’Rourke is using the judicial system to harass him.

“It’ll waste a ton of the state’s money on a nothing case,” Williams insists. “If you’re going to screw with my life over something that didn’t happen, I’m going to make everyone who made it happen miserable in return.”

And so the battle for supremacy in Ladmoland marches on. The citizenry continues to shuffle its feet, longing for happier times — maybe a new Roger Ramjet adventure, or a visit from Marshall Good, or even one of those stories from Aunt Maud, the ones that always end with once-happy children being forced off an emotional cliff. Instead they’re getting behind-the-scenes turmoil, a puerile pie-fight between Mr. Grudgmeyer and Ladmo. It’s messing up their memories of better days, and screwing with their hopes for a happy ending.