To Roxlo, this minor, temporary obstacle offered a taste of the coming three years for her neighborhood, where the city of Phoenix plans to install a massive pipeline as a hedge against looming cuts to its water supply. Construction is expected to begin late in 2020.

The 66-inch pipeline (i.e. five and a half feet) would bring water from sources like the Salt River Project to some 400,000 people in north Phoenix, an area that currently depends on Colorado River water, a source that is dwindling as the Southwest enters its third decade of drought.

Next year, Arizona is slated to take a small cut — just shy of 7 percent — to its supply of that water, a deficit that is expected grow in the years beyond. Because of the way water priorities are arranged in Arizona, Phoenix itself won't be affected by next year's reductions, and probably not even the year after that, but at some point, the city expects to take a hit.

All of this means that the city needs to ensure that people in north Phoenix have water, and it needs to do so well before the Colorado River drops to severe shortage levels and north Phoenicians are cut off.

The city says it is acting as swiftly as possible to build vital infrastructure in advance of dry times.

“These projects are not projects that you throw up in six months," said Troy Hayes, an assistant director at the Phoenix Water Services Department. "It takes years to plan and years to design and it takes time to construct."

The city doesn't expect cutbacks in 2020, or even 2021, but "it's really hard to tell," he added. "We want to be ahead of any shortages that could happen.” The city is still hammering out key details like where the pipeline would go, Hayes said.

Nevertheless, plenty of residents, like Roxlo, and local activists who speak for the park, are extremely troubled by its planning, and over the past two months, they've begun lobbying the city to listen to them.

Roxlo, for instance, pointed to concerns about congestion, noise, and dust that would choke her neighborhood as a result of the plans that the city has presented publicly so far, not to mention what she sees as shoddy communication from the city."We want to be ahead of any shortages that could happen.” - Troy Hayes, Assistant Director, Phoenix Water Services Department

tweet this

Libby Goff, a board member of the Phoenix Mountain Preserve Council, cited fears that what remains of Phoenix's pristine and shrinking desert will take years to recover if a pipeline runs through it as planned.

The tension exemplifies the struggles, at a local and personal scale, of moving forward with projects that are crucial to secure cities' futures in the face of challenges like drought and climate change. City officials admit that they are having a hard time finding a balance between the planning the projects and keeping residents informed.

For her part, Roxlo insisted she is not against a new pipeline — she just wanted the project to be done smartly, and well.

“This is not a NIMBY thing,” she told Phoenix New Times, using a common acronym for the "not in my back yard!" attitude. “We just see other options that seem reasonable.” As she recently wrote in a petition to City Council members, "Our neighbors do not want you to simply divert this pipeline to another residential area. We ask that you ... modify the pathway to a safe and secure location."

Goff, who described the Phoenix Mountain Preserve Council as a watchdog group, worried that the fragile desert through which the pipeline is expected to be tunneled will be altered for decades, despite the city's assurances to re-vegetate the area once the pipeline is done.

"Even if you replant native plants, it's not going to be the same as it was before it was ripped up," Goff said. "It just takes so long to recover."

Meanwhile, neighbors share theories, some of them conspiratorial, about what the pipeline is really for, among rumors of backdoor dealings that heighten their mistrust in local government. Nearly every yard around the Madison Heights neighborhood seems to have the same carrot-orange sign spiked into it, featuring two prominent words against a backdrop of mountains: NO PIPE.

Between a Drought and a Hard Place

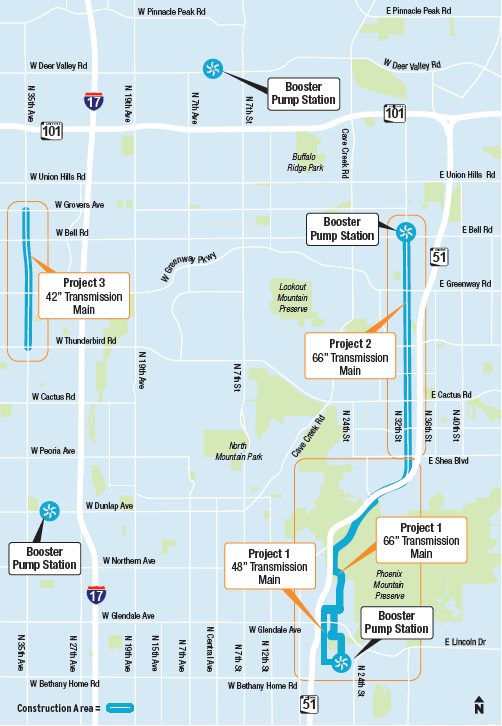

The first time Roxlo heard of the pipeline was this fall, at a meeting on October 24 organized by the city and held at the local elementary school.There, she learned that the pipeline, for which the Phoenix City Council approved funding back in January, would run from the 24th Street Water Treatment Plant, just south of Granada Park at Lincoln Drive and North 24th Street, to the Union Hills Water Treatment Plant in northern Phoenix.

That meeting showed the new pipeline coursing north, more or less right through the neighborhood (it also shows upgrades to an existing four-foot water main that the city says is at risk of "imminent failure"), Roxlo recalled. While city representatives dispensed the information to Madison Heighters and Granada Parkers who attended, it didn't ask for their feedback, she added.

The publicly available plans for a drought pipeline in Madison Heights and Granada Park.

City of Phoenix

Her fear: Construction would block up North 22nd Street, the sole ingress and egress for some 335 houses in the area nestled between State Route 51 (the Piestewa Freeway) and the Phoenix Mountain Preserve. She imagined trucks clogging the street and the quiet lanes spreading north of it, in a more extreme version of the problem of the pickup parked alongside her front curb that morning, hindering police or fire trucks that needed to get through.

And when she looked at a map, she thought she could see plenty of other options that, it would seem, made more sense, like running the pipeline along State Route 51, or the Salt River Project Canal. A few days after the meeting, she laid out her concerns in a letter to Kathryn Sorensen, the Phoenix Water Services director.

It didn't go well.

The city "has not allowed for community input on any level," Roxlo wrote in the letter, which she also sent to City Council members. She shared a copy of it with New Times. The pipeline wouldn't protect the mountain preserve, and "once one pipeline is constructed future pipelines and maintenance will continuously degrade our limited, fragile desert land," she continued.

She also wrote that she'd heard "reports" that the water was for future development, and not for current residents.

"What is the rush? If this pipeline is for future drought conditions ... we have time to incorporate community and environmental concerns into this project," she added. "We just need one well planned and implemented utility corridor in the vicinity of my neighborhood. We already have three," Roxlo concluded, referring to State Route 51, the Salt River Project canal, and the Maricopa County Flood Control Channel.

In a written response two days later, Sorensen offered several firm answers.

First, the pipeline would be used to transport water for current Phoenicians, and "is not being constructed for the purpose of providing water for growth," she wrote.

The letter also included facts about the Colorado River, its expected shortages, and the need for Phoenix to invest now in infrastructure: "It was a lack of proactive planning and investment in infrastructure that led Cape Town, South Africa, to the verge of Day Zero recently," Sorensen wrote. She even included a URL to the Wikipedia page for Cape Town water crisis.

She also seemed flatly reject the possibility of putting the pipeline along State Route 51 or the other corridors that Roxlo had referenced. "Even were we successful in receiving the relevant permissions and permits from these organizations to construct the Pipeline on their rights-of-way, which is questionable, our infrastructure would be subject to removal on request from these agencies and at our cost at any future point in time," she added.

Ultimately, Sorensen chastened Roxlo that "installation of a large pipeline in the middle of a major metropolitan area is disruptive. Unfortunately, there is no avoiding this reality, and difficult tradeoffs must be made for the long-term benefit of all the city's residents."

Roxlo wrote another response, signed by dozens of her neighbors, begging the city to reconsider its plans.

'Nothing's Decided'

Somewhere in there — before, during, or after the flurry of letters, but not actually because of them — the city changed its tune about the route that the pipeline would follow, which according to Hayes, hadn't been settled in the first place, even though Roxlo understood the decision-making to be "90 percent" done."Nothing's decided," Hayes told New Times a few days before Christmas.

The city is now negotiating with the Arizona Department of Transportation to potentially use State Route 51, Hayes said. Officials are trying to work out an agreement that would prevent any eventuality of having to someday move the pipeline if placed along the freeway, which was one of Sorensen's concerns.

An ADOT spokesperson confirmed that the department had had discussions with the city about the right-of-way but deferred to the city on the specifics of those talks.

"We're having positive discussions with ADOT," Hayes told New Times. "I'm extremely hopeful that we can figure something out, but we're not there yet."

He said the conversations with ADOT were prompted by a meeting and walk with members of the Phoenix Mountain Preserve Council, in early October, which took place weeks before the meeting where Roxlo learned about the pipeline.

Goff said that the Phoenix Mountain Preserve Council's October meeting with the city, in which most of the time was taken up by council members asking questions of the city, was unsatisfying.

"We asked a lot of questions," Goff recalled. "We were not really happy with a lot of their answers, because at the point, a lot of their answers were vague."

One of those vague answers, she said, was why the city had chosen the route it did — the one that would cling to North 22nd Street before blasting through a ridge of the Phoenix Mountain Preserve.

Through a public records request, an attorney for the Phoenix Mountain Preserve Council had gotten a copy of an alignment study by the city that looked at other routes for the pipeline, including one that went up Cave Creek Road. "We didn't understand why they dismissed that," Goff said.

According to Hayes, those conversations with the Phoenix Mountain Preserve Council prompted the city to reconsider the pipeline route. Negotiations with ADOT began in November and should conclude imminently, perhaps around the New Year, he said.

Why Sorensen's letter from late October seemed to reject the possibility of an alternate route remains unclear. When asked about it, Hayes hedged, warning about the risk of making a commitment the city couldn't keep.

But it is possible that the pipeline will no longer follow North 22nd Street, he allowed.

A sign opposing the drought pipeline sits outside an entrance to the Phoenix Mountain Preserve, which the pipeline would tunnel through.

Elizabeth Whitman

A Work in Progress

In short, the city is struggling with messaging. As it works on its own, evolving plans, it hasn't been able to get the right information to the community at the right time, and now, it seems, just about everyone is frustrated."There's a lot of information out there that's not exactly true," Hayes said. There's the inaccurate belief that the water would be used for new development, which, he said, has "come up every time we present," or that construction on the new pipeline would begin in January. It's the old, 48-inch pipeline that is slated for rehabilitation first, but that work won't begin until March, Hayes said, while the construction for the drought pipeline is supposed to begin sometime in the fall.

Residents like Roxlo learned of the pipeline project only in October, a year after the Phoenix City Council authorized a contract for it. It took a year to get the word out to the community, Hayes said, because the planning was, and still is, in progress.

"We're trying to figure out how and what we're doing in the design process," Hayes said. At the October meeting, he continued, plenty of people were frustrated because the city didn't have a lot of information to share, and because the city didn't hold the meeting sooner.

"We try to strike a balance," Hayes said. “As we get into drought ... there’s going to be these sorts of challenges for a lot of communities. How do you address that? It’s an inconvenience but for the greater good.”

The city plans to hold its next neighborhood meeting and give updates on the pipeline in late January or early February.

In December, a week before Christmas, Roxlo and a neighbor, Jeannie Swindle, penned a petition to the City Council, asking its members to pause the pipeline project until the city redoes an alignment study that they criticized as "inadequate." That study, they said, failed to adequately evaluate concerns from the community or those regarding environmental impacts, among other issues."If we're willing to destroy parts like this. pretty soon we don't have any desert preserves left." - Libby Goff

tweet this

"We believe that the proposed pipeline project will be one of the most expensive infrastructure projects in the City's history," they wrote. "Yet, the WSD [Water Services Department] has engaged in little more than a desktop study of the costs and potential impacts of the project."

They are also asking for the City Council to put the matter on the agenda for a future meeting, "so that all council members vote on the alignment before the project moves forward."

Goff, of the Phoenix Mountain Preserve Council, said that the council had managed to secure a spot on the agenda for the January 15 meeting of Phoenix's Land Use and Livability Subcommittee Meeting.

Her hope was to convince its council members — Debra Stark, Carlos Garcia, Betty Guardado, and Thelda Williams — to send the matter to the full City Council, which would then vote on the question of whether the pipeline could go through the preserve.

The Phoenix Mountain Preserve Council occasionally coordinates with Roxlo and other residents, when their interests align, Goff said.

Goff doesn't live in Roxlo's area, but she hikes frequently in the Phoenix Mountain Preserve, and she has chipped in to help buy the orange signs and T-shirts that declare "NO PIPE." Goff even places one of the signs in a window of her car as she drives about town.

“Our concern is that the preserve is very often the easiest place to go for one of these things,” Goff said, because a park has no residents and no businesses to disrupt. "If we're willing to destroy parts like this, pretty soon we don't have any desert preserves left."