Every summer, you face an impossible choice.

In Phoenix’s triple-digit summer heat, you need air-conditioning to keep cool. Your heart and your circulation aren’t what they used to be.

Keep your home cool enough, and face a bill you can’t pay. Turn the air conditioning off, and risk overheating, landing you in the emergency room or worse.

What do you do?

In Arizona, responsibility for this potentially deadly dilemma has landed in the lap of utility regulators at the Corporation Commission.

Last June, after learning about a woman's heat-related death after Arizona Public Service cut her power over $51 owed, the five corporation commissioners temporarily banned summer shutoffs for unpaid bills.

For the last seven months, policymakers there have mulled over how to formulate permanent disconnection rules, so that people don’t die in their homes because they are too hot.

But as several local scientists and public health experts pointed out during a wide-ranging workshop at the commission at the end of January, this problem is not just a utility issue. It’s also an economic issue and a social one, a matter of affordable housing, geography, climate, and many other things.

Although other agencies and organizations provide assistance with the heat, utility bills, housing, or income, it is the Corporation Commission that is now tasked with creating deliberate, life-saving policy.

At the recent all-day workshop, which did not include any of the actual people who would be most affected by disconnect rules, staffers and commissioners seemed overwhelmed and eager — even desperate — for a simple solution.

“We are basically sinking here,” Elijah Abinah, utilities director at the Corporation Commission, told Phoenix New Times after the workshop. “There’s too much going on.”

That morning, Dr. Rebecca Sunenshine, director of the Maricopa County Health Department, presented data comparing rates of indoor heat-related deaths with outdoor temperatures. For 30 percent of those deaths, outdoor temperatures were 105 degrees or cooler, the data showed.

Thirty percent is too high, Abinah said. Notably, the working threshold to trigger shutting off the electricity in households with unpaid bills in the latest draft of revised rules is 105 degrees Fahrenheit. He asked if Sunenshine could suggest a different number.

Sunenshine deferred to David Hondula, an assistant professor at Arizona State University’s School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, who also presented that day.

“There is no magic number,” Hondula told staff and commissioners. “This is a difficult judgment that someone will have to make.” He added, delicately, that Arizona has appointed and elected officials to make those kinds of hefty decisions.

Those officials face myriad questions: Should a ban on power cuts be tied to a specific temperature? Perhaps no shutoffs above 105 degrees? Or, should it cover a limited time of year? If people rely on the moratorium and don't pay their utility bills over the summer, what are the consequences of that debt? If they can't catch up, do they still get power next summer?

Money aside, would a moratorium on summer shutoffs really save lives?

Others who weighed in, like ASU urban heat researcher Melissa Guardaro, wanted even more nuance: How many people have died because they chose to forgo air conditioning, because they couldn’t afford it?

People’s lives and welfare hang in the balance. Paying these bills can be a source of “deep stress,” Guardaro told New Times during a break in the workshop.

Now, summer is just around the corner.

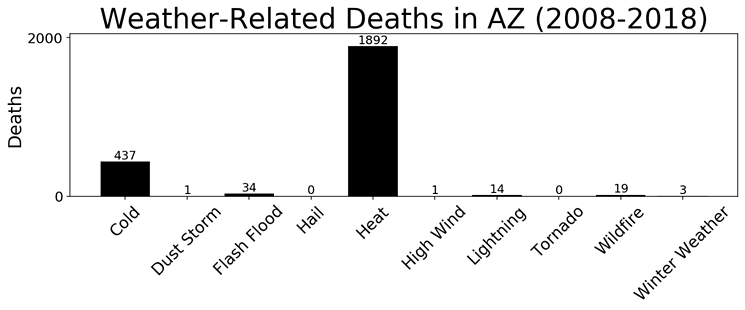

In Arizona, heat has killed more people than any other environmental cause, Paul Iñiguez, science and operations officer with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and National Weather Service, told the Corporation Commission during his presentation at the workshop.

From 2008 to 2018, 34 deaths from flash floods and 19 deaths from wildfires pale in comparison to the 437 deaths from cold and a whopping 1,892 deaths from heat in the state, federal and state data show.

In Arizona, heat kills more people than any other weather-related cause.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and Arizona Department of Health Services

In some of the cases, death records show, air conditioning was turned off, perhaps to save money. In a few cases, victims' homes had no power at all.

Last June, for example, 82-year-old Eugene Kaznowski was found dead in his home in Phoenix, his air conditioner off. Inside, the temperature clocked in at 99 degrees Fahrenheit.

The county medical examiner concluded that Kaznowski, 82, had died from a combination of chronic illnesses — he had high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease — and the heat, according to the report, which New Times obtained through public records request.

Had the moratorium from last June saved lives? Commissioner Lea Marquez Peterson wanted to know.

“It’s something that we’re very interested in looking at,” she added, saying that she’d spoken with Hondula about it.

Hondula later told New Times that ASU is working on obtaining and studying the data they need for such a study.

In recent years, the number of heat-related deaths has risen steadily in the Valley.

Last year, 190 people died in some way because of the heat, county data show. Temperatures are rising too. Climate projections show that “temperatures will be increasing in the Southwest United States,” Iñiguez said. “Phoenix is the largest and hottest city in the country.”

In a county survey, 30 percent of residents, or 1.35 million people, said they could afford to run their air conditioning only during the day or the night, but not both, Sunenshine said. In another survey, 60 percent of people who were homebound said they either "always" or "sometimes" felt hot during the summer; cost was the biggest barrier to running their air conditioning.

Cynthia Zwick, executive director of the anti-poverty nonprofit Wildfire, said that an affordable energy bill should be about 6 percent of a person’s household income. But for people living at half the federal poverty line ($12,490 a year for an individual), energy bills can soar to 40 percent of their annual income.

By the end of the day, only Commissioner Lea Marquez Peterson and Chairman Bob Burns remained at the workshop; the three other commissioners had trickled out after lunch.

Corporation Commissioners dropped in and out of Thursday's workshop. By the afternoon, just two of the five remained.

Elizabeth Whitman

The next step in this process is to hold another workshop, perhaps in May or June, he told New Times. Technically, the formal rule-making process hasn’t even begun yet, and staff, who make recommendations that commissioners vote on, would be unlikely to submit revised proposed rules until the end of the summer.

With rule-making typically taking about nine months, Abinah envisioned the final rules being done by June of 2021.

Until then, utilities will still be banned from disconnecting customers for nonpayment by their own rules, because the Commission’s emergency rule that imposed the June-to-October moratorium expired last year.

Asked why the process was taking so long, considering that the last workshop was in September, Abinah mentioned that hundreds of companies are regulated by the Corporation Commission, that several major rate cases are in the works, and that the commission could use more staff members.

He joked that perhaps New Times could call the governor’s office and make the case for hiring more people.

“There’s a lot going on at the Commission,” Abinah said.