"It was such a racist time in our history,” recalls Carmen Guerrero. “We knew all of us, not just undocumented immigrants, would be affected.”

Guerrero, a Mesa artist, is referring to SB 1070, the controversial law that put Arizona on the map for racial profiling, leading to boycotts throughout the state. Adopted in July 2010 — exactly a decade ago this week — it required legal immigrants to carry their registration papers and gave law enforcement officers the power to ask people they stopped for other reasons to show their immigration papers if the officers suspected they were in the country illegally. It also gave officers the power to arrest immigrants suspected of deportable offenses without a warrant, and prohibited undocumented immigrants from soliciting work.

The key figures in SB 1070’s creation — Arizona Senator Russell Pearce, who sponsored it; Governor Jan Brewer, who signed it into law; and SB 1070’s perhaps most famous supporter, Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, who later fueled the Obama “birther” conspiracy theory — are all gone from office now. The Supreme Court gutted much of the law in 2012.

But despite various efforts, SB 1070 has never been officially repealed by the Arizona Legislature. And the law’s impact on Arizona’s collective psyche is evident in the culture here. It’s present in the works of artists like Guerrero and others who protested 10 years ago, and all those who’ve made works addressing immigration, racism, and border politics in the decade hence. “Looking back, SB 1070 was bigger than we thought,” Guerrero says. “It launched an art movement that’s still going strong today.”

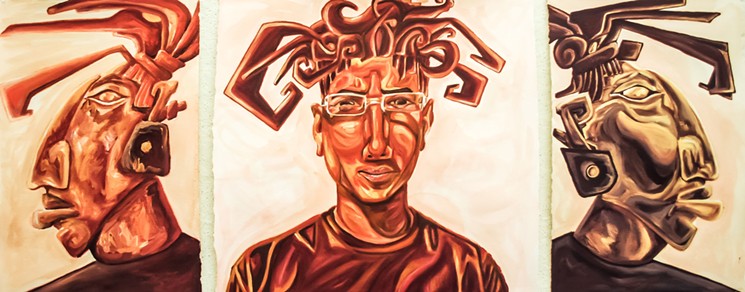

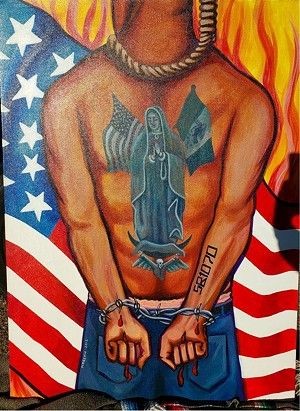

Martin Moreno finds inspiration in muralists who worked in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution.

Martin Moreno

Angel Diaz painted a mural in an alleyway behind Barrio Café, where Chef Silvana Salcido Esparza launched an ongoing mural project called Calle 16 in response to SB 1070. Today, the mural depicts protesters with signs decrying both Arpaio and Donald Trump. “After the Mexican revolution, people went back to their ancestral ways, and artists painted their stories so people saw their history on the walls,” Esparza says. “I wanted artists to have a place to tell our stories, including our struggles and our successes.”

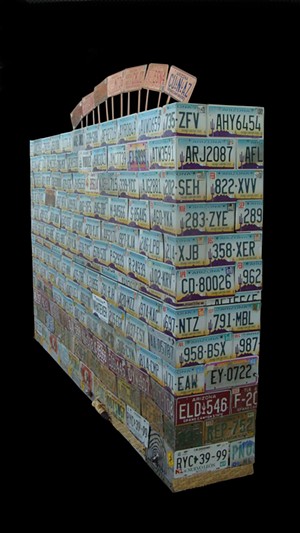

Jose Benavides uses license plates to explore issues of place, migration, and identity.

Kelly Peterson

El Mac is a Los Angeles artist with Phoenix roots who found inspiration in a friend who had immigrated from Guatemala. He used as his canvas a museum elevator shaft that towers over Main Street in Mesa. “I painted an image of an immigrant who’s participating here and adopting aspects of America culture,” El Mac told New Times. “I didn’t want to be overtly political.”

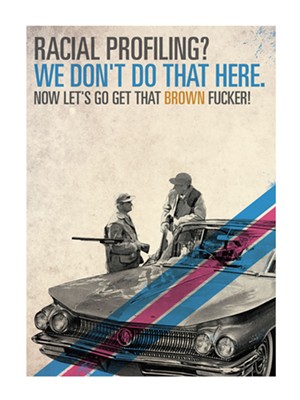

Safwat Saleem is an artist born in Pakistan who still recalls the hatred directed against Muslims in the aftermath of 9/11. He explored the wider context of racism for a series of campaign-style posters he called “A Bunch of Crock.” He was halfway through the naturalization process at the time. One piece featured two men standing near a car while armed with guns. Above them Saleem wrote: “Racial Profiling? We Don’t Do That Here. Now Let’s Go Get That Brown Fucker!” “That was the first political art I made,” Saleem recalls of the series. “In some ways, I feel a worse existential threat now, because the racism is coming from the presidential level.”

Gloria Martinez-Granados creates work informed by her own experiences as a DACA recipient.

Gloria Martinez-Granados

Gloria Martinez-Granados made mixed-media works based on photographs of migrant children who’ve died in detention during the Trump era. “All my work centers on immigration since I’m undocumented,” she says. “DACA was counted as a victory, but it’s so scary the way Trump talks about mass deportation.”

Julio César Morales grew up in Mexico and often traveled across the border as he was growing up. He created a red neon sign that plays with the word “Invaders,” prompting people to reflect on who that word applies to in the context of the borderlands. “Invaders was in a show that we all boycotted because of SB 1070, but one thing I learned is that if you want to make change, you have to do it from within,” he recalls.

Edgar Fernandez started painting murals exploring his cultural roots after seeing Moreno and other artists making work with social justice themes. “Ten years ago when SB 1070 happened, it was the first time I got introduced to painting murals,” he recalls. “It’s important to me because a lot of indigenous and Chicano art is erased,” he says. Fernandez’s body of work also includes a painting addressing racism called Too Brown for Amerikkka.

Hugo Medina worked with local youth to create side-by-side murals with immigration themes near Crescent Ballroom. One depicts a group of diverse immigrant faces. Another features a young girl opening a cage to set free monarch butterflies, which are best known for their migratory flights. Medina is one of several artists who worked on the Calle 16 project during its early days. Medina was 8 years old when his parents moved from Bolivia to the U.S., and recalls living in fear until he and his parents were granted citizenship. Earlier this year, he painted a mural depicting two immigrant children in cages. “I hope my work starts a conversation,” he says. “If we don’t address history, it gets repeated.”

Francisco "Enuf" Garcia worked with several community members to paint a south Phoenix mural inspired by the DREAM Act. The mural included side-by-side partial portraits of both Chavez and Arpaio. Both of Garcia’s parents hail from Mexico, and he’s deeply rooted in Chicano culture. “Artists were already making things, but we started to see a lot more political art after Calle 16,” he recalls. “When there is art growing, there is positive movement and activism grows.”

Margarita Cabrera worked with community members to create cactus using Border Patrol uniforms.

Lynn Trimble

Margarita Cabrera collaborated with the community to make soft cactus sculptures that speak to immigrant dreams using fabric from green U.S. Border Patrol officer uniforms. Every cactus was stitched with words and imagery used by immigrants to describe their own experiences. “I believe that art has the power to not only reflect the world around us, but also to change the world around us,” Cabrera explained during a 2012 artist talk about these works. “It’s my responsibility as an artist and as an immigrant myself to reflect these situations and to make my work process about these issues.”

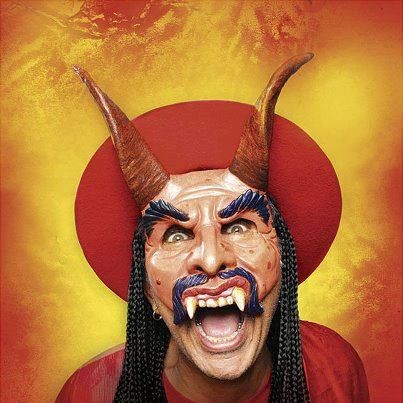

Zarco Guerrero created giant papier-mâché heads modeled after Arpaio and Brewer, which friends wore while protesting SB 1070 at the Arizona State Capitol. The artist marched between them wearing his own El Diablo (devil) mask. Guerrero worked on the successful effort to have Pearce recalled in the aftermath of SB 1070, along with his wife and fellow artist Carmen Guerrero. “You had a bunch of artists that were never politically engaged before,” recalls Zarco Guerrero. “They were united in sharing images and ideology like I hadn’t seen since the Chicano rights movement.”

Annie Lopez made one of her first dresses around the time of SB 1070. Titled Official Proof, the dress was covered in images of documents tied to her identity, including her birth certificate and grade school awards. In 2013, she skewered politicians Brewer and Arpaio with a piece called Show Me Your Papers, and I’ll Show You Mine. “I think there was a shift,” Lopez says of SB 1070 days. “People were a bit more vocal, which helped to make artists feel like they could express their opinions.” Today, the fourth-generation Phoenician is working on a new dress that includes imagery from her maternal grandmother’s identification cards, plus language from SB 1070 that describes immigrants as “aliens.”

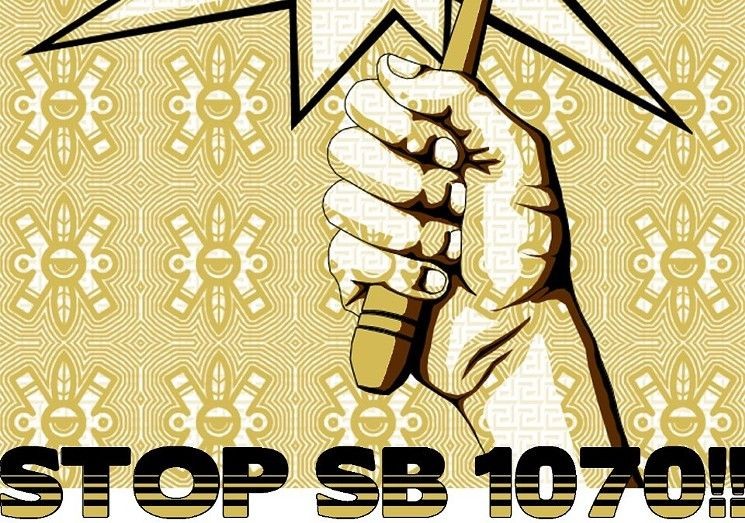

Part of a Reggie Casillas work recently exhibited in "We Are Still Here" at the Arizona State Capitol.

Reggie Casillas

Reggie Casillas made prints with social justice themes, including a yellow and white work anchored by a raised fist holding a noisemaker, with text that read “Get Loud! Get Active!” and “STOP SB 1070!” He’s married to fellow artist Gloria Martinez Granados. “Now that we’ve got so many more things that we’re dealing with, SB 1070 is sometimes in the back of people’s minds," he says.

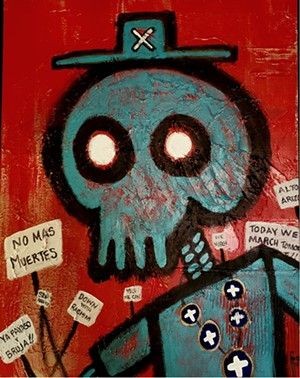

Bacpac imagines Donald Trump demanding green cards from spirits returning for Day of the Dead.

Jeremie "bacpac" Franco

Jeremie “bacpac” Franco created paintings that address Trump-era immigration policies. Her Wall of the Dead depicts the border wall as a morgue where drawers are filled with immigrants who’ve died trying to enter the U.S. Deporter in Chief references Trump’s cloaks of religiosity and militarization. “On the Day of the Dead, in the age of Trump, even the dead need green cards,” Franco says of the piece. “Even the dead are not exempted from SB 1070.”

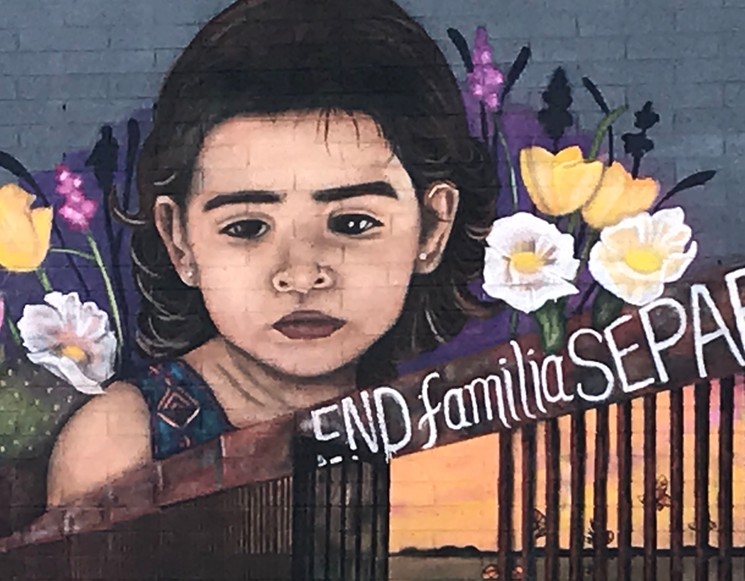

Lucinda “La Morena” Hinojos also recently made a mural decrying Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant policies, and the resulting family separations. It’s located just off Washington Street near the Arizona Capitol grounds, where protesters once marched in opposition to SB 1070. Two years ago, she painted an immigration-themed mural in south Phoenix, where she worked with a local art teacher and several students. “We want to teach the youth about culture and social justice, and that art could be their voice,” Hinojos told New Times in 2018.

Marco Albarran painted a skeletal figure standing amid protest signs with messages that include “Down With Racism” and “No Mas Muertos.” “Protest art didn’t start with SB 1070,” he says. Albarran was a farm worker before becoming an artist, and recalls being inspired by civil rights activist Cesar Chavez to march decades before SB 1070 was written. “When SB 1070 happened, artists were trying to find a way to have a voice and tell the story of what was going on.”

Lalo Cota painted sombreros cast as flying saucers hovering over the desert on a car wash located at Roosevelt Street and Seventh Avenue, only to see it demolished in 2017 to make way for a drive-thru Starbucks. “They’re like the first illegal alien spaceships crossing the desert,” Cota told New Times of his iconic sombrero imagery back in 2011. He’s also painted satirical portraits of SB 1070 personalities Arpaio and Brewer.

James Garcia wrote numerous plays focused on racism and immigration, addressing topics that include SB 1070, DACA, and a 2010 bill that banned Tucson schools from teaching a Mexican-American studies class. In 2018, he organized play readings at the Arizona State Capitol to protest Trump’s immigration policies. “I believe we may be living through the most destructive presidency of my lifetime,” he told New Times while organizing those readings. “Just when you think that it can’t get more scary, something even more terrifying comes along.”

Still shot from a film about the Postcommodity land art installation Repellent Fence.

Michael Lundgren/Postcommodity

Raven Chacon, Cristóbal Martinez, and Kade L. Twist worked together while they were all part of the Postcommodity collective to create a land art installation called Repellent Fence, using giant “scare-eye” balloons they first discovered when Martinez’s wife used them to repel birds from their Tempe backyard. Their installation conceived as a suture temporarily hovered across the U.S.-Mexico border for several days in October 2015. “The biggest thing artists have is the role of catalyst,” Twist told New Times in 2015.