It might be surprising to realize that David Lynch has only ever made one period piece: The Elephant Man (1980), set in the Victorian era. The rest of the director’s films, save for his 1984 sci-fi disaster Dune, take place in what presumably is the here and now. Or, more accurately, they take place in a Lynchian version of the here and now — one where time is nonlinear and past and future constantly intrude on the present. And, of course, one where the 1950s never quite ended.

That era has always been a defining one for Lynch’s films. It’s the rare influence he openly acknowledges. “The Fifties are still here,” he tells Chris Rodley in the interview book Lynch on Lynch. “They never went away....It was a fantastic decade in a lot of ways....It was a really hopeful time, and things were going up instead of going down. You got the feeling you could do anything. The future was bright. Little did we know we were laying the groundwork then for a disastrous future.”

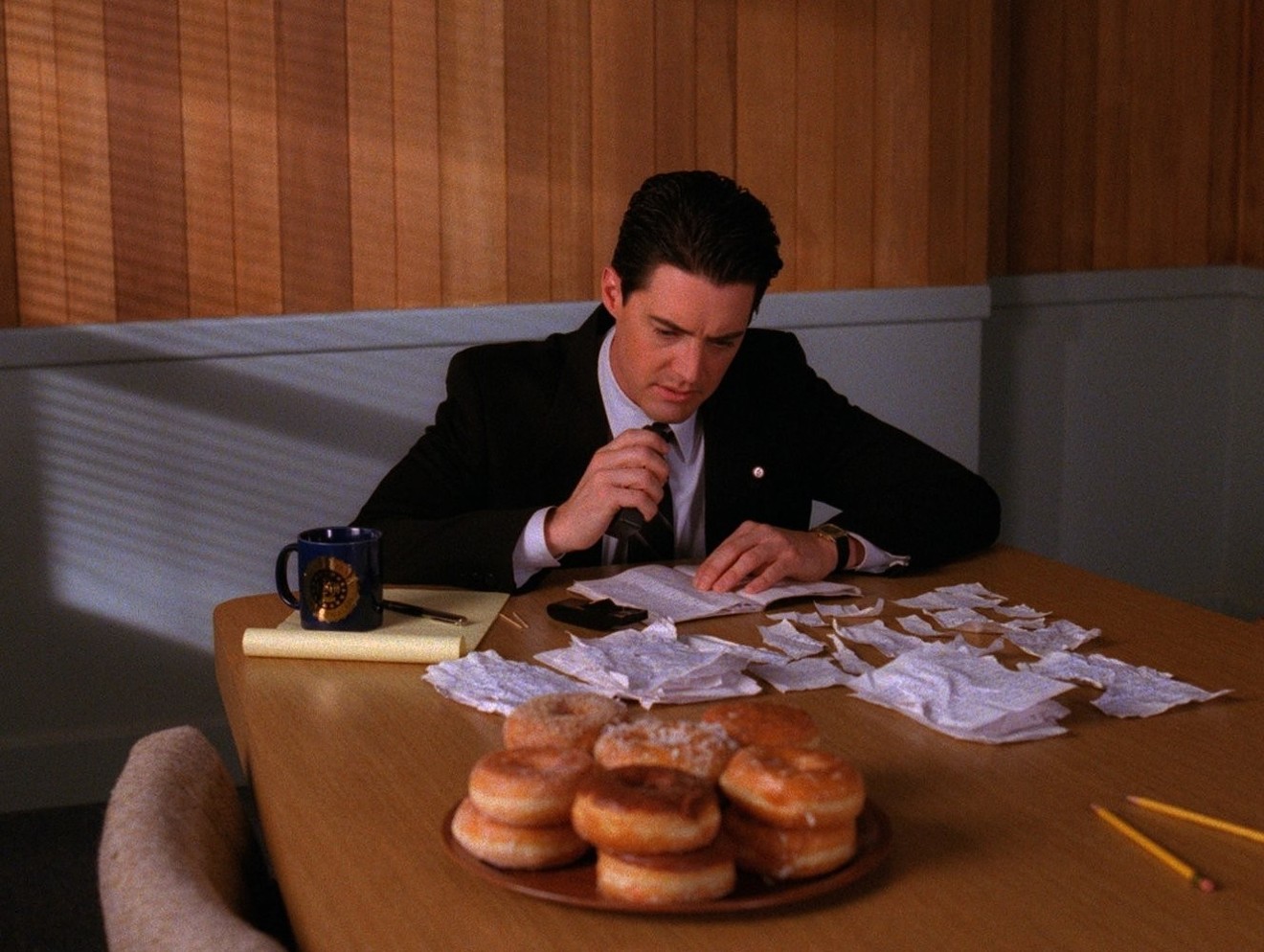

A particular kind of longing for this period hangs over Lynch’s work, as well as that work’s reception. Nobody who lived through the Twin Peaks craze of 1990 will forget that show’s mesmerizing, fetishistic pull, which affected the way people dressed and talked, even what they ate and drank. (Remember Twin Peaks parties?) For all its weirdness, the series resonated in part because of our fascination with that earlier “fantastic decade.” By melding this nostalgic aura with his more new-age influences (often expressed via Angelo Badalamenti’s score), Lynch seemed at times to have created an idealized world, one in which many of us wished we could live. And along the way, he turned himself into something of an icon. There are millions of people out there who’ve never seen a David Lynch movie but will immediately know what the word “Lynchian” means.

But what about, you know, the rape and murder, the incest and kidnapping and arson? Beneath the quaint Fifties-isms of Twin Peaks lie some of the most grisly acts ever seen on network television. But the wistful indulgences of the original show don’t work despite the horrors — they work because of them. The terror and the nostalgia are locked in a mutually dependent, parasitic embrace: The madness of Twin Peaks is fed by the repression and aw-shucks atmosphere of its setting. In exchange, that atmosphere serves as an escape from the show’s darker edges. Don’t worry about the terrifying things happening at night in the woods, Lynch and co-creator Mark Frost seem to say. You’re only a commercial break away from Sherilyn Fenn and her saddle shoes sunnily strutting into the Double R Diner.

Nostalgia is back in the air nowadays, but with a renewed, world-consuming toxicity. In an essay for the Guardian written in February, the Pakistani author Mohsin Hamid ties together various currents across the planet. In entertainment, he explores the obsession with shows like Mad Men and Game of Thrones; in technology, he discusses the digital flashbacks and imaginary idealized pasts of Facebook memories and Instagram filters. And in politics, well, there’s Brexit, the U.S. election, nationalist movements across the world, and — yes — groups like ISIS, all of which depend upon a harking-back to glorious, imaginary pasts as a salve for the fragmentation and anxiety of the present.

Is it nostalgia — born of fear and uncertainty and a desire for simpler times — that pulled audiences to Twin Peaks, then and now, and that makes Lynch a source of continual fascination, even for people who haven’t seen his work? Maybe, but recall that he has been a constant presence in our culture for decades; he was a recognizable figure well before the phenomenon of Twin Peaks, his sensibility connecting with both the ironic, art-nerd ethos of the 1980s independent music and film scene and the sun-dappled “Morning in America” messaging of the Reagan era. But it’s weird: Lynch probably has more flops than hits on his résumé, and his hits are generally modest. Over the past several decades, his vitality as a public figure — dare I use that ghastly word brand? — seems to be only marginally connected to the critical or financial success of his releases.

To put it another way: America needs David Lynch. Throughout his work, Lynch blends the textures of nostalgia with the transgressions of horror, and in so doing helps us transcend both. The contrasts of Twin Peaks are also there in Blue Velvet (1986), with its white-picket-fence, gee-whiz small-town milieu punctured by the presence of unspeakable evil. The menace gathers and becomes even more overwhelming in the later films: Mulholland Drive (2001) goes quickly from an opening of aggressive, jitterbugging quaintness to a nightmare of fractured identity and pervasive gloom. The much-maligned Lost Highway (1997), which J. Hoberman deemed a “bad boy rockabilly debacle,” starts dark and gets darker; its borrowings from the past are already steeped in betrayal and decay by the time the movie starts. And if Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive had a secret love child, and that child had a nightmare, it might look a bit like Inland Empire (2006).

Lynch helps us understand the people and the forces that hold sway over us. The director is not a particularly political person (though he occasionally jumps in in the oddest ways, as when he got involved in the presidential campaign of his Transcendental Meditation colleague and Natural Law Party candidate John Hagelin), but sometimes I wonder if our Age of Demagogues isn’t a geopolitical variation on one of his movies. In many Lynch films lurks a central figure of absolute evil: Think of Dennis Hopper’s Frank Booth in Blue Velvet, Robert Blake’s hideously grinning Mystery Man in Lost Highway, the dark spirit BOB in Twin Peaks, or the terrifying hobo behind the dumpster in Mulholland Drive. (“There's a man...in back of this place. He's the one who's doing it.”)

But these figures are not external demons. Twin Peaks constantly calls into question whether BOB is real. Could he just be a conduit for people to spiritually absolve themselves of their own murderous acts? “You invited me,” Lost Highway’s Mystery Man says. “It is not my custom to go where I am not wanted.” He is, in effect, the lead character’s jealousy and rage made manifest.

The evil, in other words, comes from within. It comes from us. Maybe that’s why Lynch’s works, for all their backward-looking dreaminess, never end with us wanting to keep on living in these environments. They end with us exhausted, anguished, screaming to get out. They end with us awakened from both the nightmare and the dream.

Lynch recognizes these dark impulses within himself: Take Wild at Heart (1990), with its relentless carnival of horrors, a film that functions not unlike a totemic spirit within his own oeuvre — a cruel vessel into which he’s poured all his rage and violence. Wild at Heart, the devil on Lynch’s shoulder, even has its opposite, angelic number: The Straight Story (1999), a picture of almost limitless sweetness and light, and the only other road movie he’s made.

Lynch hasn’t exactly been quiet in the ten years since he released Inland Empire, but he hasn’t made any new films. As Twin Peaks returns, we should consider why the show now seems so relevant, even vital — why we’re all so excited for it, decades after the original’s harrowing, deeply disturbing final shot. There is, no doubt, nostalgia at work in the Peaks revival — nostalgia this time not just for the show’s setting but, at least for many of us, for that time in our lives when we presumably worshipped Twin Peaks (and before it pissed us all off). But this time, there’s also something deeper, and more hopeful, about the show’s return and our eagerness for it. Because David Lynch’s work is more than just a cinematic pathway into the past. It is also a way out.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]