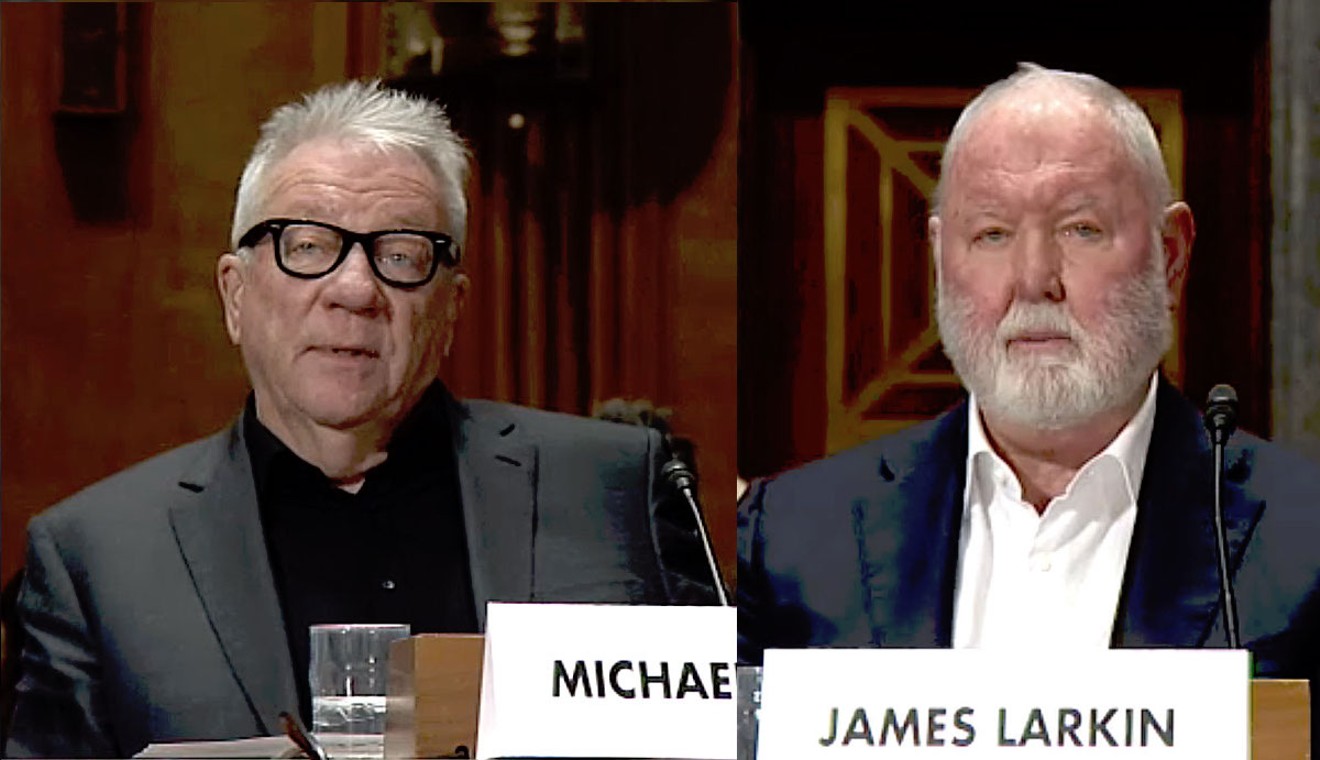

Michael Lacey sits at the bar of an Italian eatery in Phoenix’s upscale Biltmore neighborhood in early November, drinking Macallan single-malt Scotch and recalling his recent stint in the Sacramento County jail. National and international news splashed mugshots of Lacey, his longtime business partner Jim Larkin, and Backpage.com CEO Carl Ferrer all over the internet.

The three businessmen had been arrested and held for four days in October on allegations of conspiracy to pimp and pimping, though none of them qualifies as a latter-day Dolemite or Huggy Bear, nor is anyone suggesting that they ever coerced anyone — physically or otherwise — into the world’s oldest profession.

Still, California’s then-attorney general and soon-to-be U.S. Senator, Kamala Harris, had the three men collared on the theory that, as the former (Lacey and Larkin) and current (Ferrer) owners of the online listings behemoth Backpage.com, they had derived income from prostitution because the ads in the adult section of the site profit from commercial sex, sometimes involving children.

This, despite ads on Backpage for escorts, body rubs, phone sex, dominatrixes, and other such services being unquestionably legal.

The public-menace view of Backpage, which also hosts more mundane advertisements for babysitters, roommates, and folks selling old toasters, is what motivates its enemies to drive it out of business altogether and punish those who created and own it. Started in 2004 as a competitor to Craigslist, it has since become a cash cow worth an estimated half-billion dollars, pumping out $135 million in net proceeds in 2014. The company recently boasted 180 employees, and 943 individual sites in 97 countries and six languages.

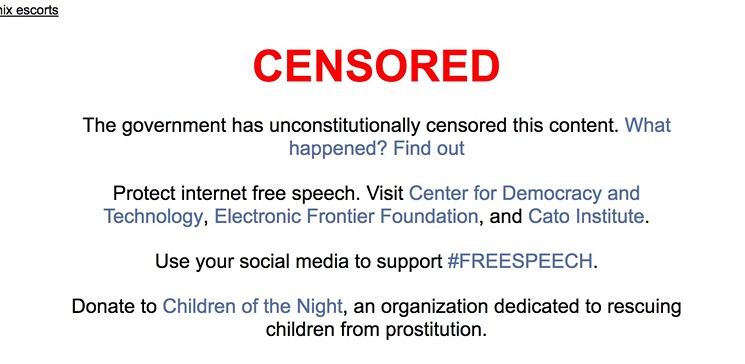

Last week, Backpage’s foes scored a major victory on the eve of its execs’ January 10 appearance before a U.S. Senate hearing on human trafficking. Caving to the pressure, Backpage shuttered its adult section, displaying the word “censored” in red beneath each adult subcategory on its site while vowing to fight on.

At stake in this donnybrook are the First Amendment rights of online advertisers and publishers, as well as Section 230 of the federal Communications Decency Act (CDA), which grants immunity to owners of interactive websites for third-party content, an umbrella under which the internet has flourished, protecting such tech giants as Google, Twitter, and Facebook, as well as countless smaller entities. The ongoing anti-Backpage campaign by politicians and prosecutors flies in the face of numerous court rulings in Backpage’s favor that support its right to exist.

In November, much of this recent history was still to come, though you didn’t need Sybil the Soothsayer to see that Backpage’s future was a veritable minefield. Larkin and Lacey say that they haven’t owned the company since 2014, but Harris fought the trio’s release on bond, arguing that any money they put up would be ill-gotten, which explains the four days it took for them to get set free.

With Lacey’s grizzled countenance — one that calls to mind a cross between crime writer Edward Bunker and gutter poet Charles Bukowski — gravelly voice, and tattooed letters on his fingers that spell out “Hold Fast,” he was better outfitted to play the part of prisoner than either Ferrer, who looks like a middle-aged record store owner, or Larkin, who, with his big white beard, would seem more at home in overalls, practicing his woodworking skills.

Sipping his Scotch, Lacey tells how there was nothing to do in jail except stare at a communal television set twice a day. He was on the second tier during one of these TV breaks, looking down on the crowd below, when local news showed footage of him, Larkin, and Ferrer in court, decked out in orange jumpsuits, standing in a cell located inside the Sacramento superior courtroom where they’d been arraigned.

“Everybody’s watching TV, and I come on, and Jim and Carl ... and then everyone slowly turns and looks up at me,” Lacey says with a chuckle.

The next morning, when he descended to the main floor, two rather large men approached him.

Recalls Lacey: “This is when they say, ‘Hey, you Mister Backpage?’

“I didn’t know where this was going. So I said, with the sternest expression possible for an elderly white man, ‘Yeah, I am.’

“Then, [one of them says] ‘Man, my baby-mama loves Backpage!’

“And from then on, I was Mr. Backpage,” he says with a laugh.

Freshman U.S. Senator Kamala Harris brought pimping charges against the current and former owners of Backpage last year, while still California’s attorney general.

Lonnie Tague/Department of Justice

Lacey maintains that what the authorities in California fail to understand is that, “Unlike a lot of pale people, I’ve been to jail before.”

That is to say, this isn’t Lacey’s first bull ride, and it’s not the first time his sense of humor has thinly masked an Irish love of fisticuffs and thirst for revenge.

I recall that long night in October 2007, when a handful of reporters waited into the wee hours to see Lacey emerge from Phoenix’s Fourth Avenue Jail, after he and Larkin were arrested separately by deputies dressed in plainclothes in the employ of then-Sheriff Joe Arpaio.

Arpaio and his pet prosecutor, Maricopa County Attorney Andrew Thomas, had teamed up, setting sights on their fiercest critic, Phoenix New Times. A special prosecutor was hired, and broad, illegal subpoenas were sent out under the imprimatur of a yet-to-be-impaneled grand jury, seeking information on the weekly’s online readers.

“We are going to sue Kamala Harris’ grandstanding butt. There is such a thing as prosecutorial immunity, but it’s not absolute. She knew she didn’t have the authority to do this.” —Michael Lacey

tweet this

Basically, the fight was rigged from jump. So Lacey and Larkin, co-founders of New Times and then executive editor and CEO, respectively, of the Village Voice Media chain of alt-weeklies — which they sold to company executives in 2012 — published a cover story that gave details of the grand jury that was not yet a grand jury and outing the subpoenas as a First Amendment violation.

In short order, the men were wearing handcuffs, charged with revealing grand jury secrets, a Class One misdemeanor.

Larkin was cited at a substation and released, while Lacey was booked into jail, a prolonged pain-in-the-keister process that can take a half-day or more. As he emerged after being cut loose, he spoke to reporters, comparing the events of the day to the eccentric Disneyland attraction, Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride.

While in custody, Lacey explained, a jail denizen asked him what he was in for.

“Writing,” he told the chap.

Lacey and Larkin had the last laugh. The public outrage in the wake of the arrests was deafening. Thomas gave a press conference and announced that he was dropping the prosecution. The county attorney would end up disbarred in 2012 for other abuses of power. Lacey and Larkin sued in federal court for false arrest, and after a prolonged legal battle, scored a $3.75 million settlement from Maricopa County.

Fast-forward nine years, and it seems like history’s repeating itself.

“We are going to sue Kamala Harris’ grandstanding butt,” Lacey told me in November. “There is such a thing as prosecutorial immunity, but it’s not absolute. She knew she didn’t have the authority to do this.”

U.S. Senator from Ohio Rob Portman, chairman of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, with anti-sex trafficking advocate Cindy McCain, following the recent Backpage hearing.

Stephen Lemons

In fact, in 2013 Harris was one of 47 state attorneys general who signed a letter to Congress asking it to amend Section 230 of the CDA to allow state authorities to prosecute companies like Backpage that have “constructed their business models around income gained from participants in the sex trade.”

So it should have come as no surprise to Harris when Sacramento superior court Judge Michael Bowman issued his final ruling in December, finding, as other courts have before and since, that Backpage has Section 230 immunity from civil and criminal liability for anything posted to its site by a third-party advertiser.

“Congress has precluded liability for online publishers for the action of publishing third-party speech and thus provided for both a foreclosure from prosecution and an affirmative defense at trial,” Bowman wrote in his final ruling, referring to Section 230. “Congress has spoken on this matter and it is for Congress, not this Court, to revisit.” [Emphasis in original.]

Regardless, in the waning days of her tenure as California AG, just before Christmas, Harris’ office refiled the pimping charges against Lacey, Larkin, and Ferrer, tacking on a few more and adding 27 counts of money laundering for good measure.

In October, Harris, in cooperation with the Texas attorney general, had Ferrer pinched as he stepped off a flight from Amsterdam to Houston, while members of the Texas AG's law enforcement unit raided Backpage’s Dallas offices. Warrants were issued for Lacey and Larkin’s arrests, and the men traveled to Sacramento to turn themselves in, only to find themselves booked and held as Harris fought to deny them bail.

They eventually bonded out: Ferrer for $500,000, the other two for $250,000 apiece. And they triumphed, at least for the moment. But it was not without some anguish. Having your name and likeness associated with pimping, child sex trafficking, and “modern-day slavery,” as the Texas AG called it, is not the kind of reputation anyone wants, even if you beat the rap.

Nor are the men spring chickens. Though Ferrer is 55, Lacey and Larkin are in their late 60s. And now, the three men face arraignment on January 24 in Sacramento for the new charges.

The California AG’s refiling of the charges is but one recent development signaling that Backpage’s battles will drag on, even in the wake of Backpage’s decision to do what Craigslist did in 2010 and close its adult section, though it’s unclear if the change is permanent. Backpage’s attorneys would not comment on the development other than to refer to statements on Backpage’s website, which say that Backpage is bowing to “extra-legal tactics” and “an accumulation of acts of government censorship.”

Senator Claire McCaskill of Missouri, ranking Democrat on the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, in a fit of hyperbole, called Backpage's business practices "the definition of evil."

Stephen Lemons

Another dark sign in the Backpage fight came at the end of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations’ January 10 hearing, after five current and ex-Backpage honchos, including Lacey, Larkin, and Ferrer, declined to answer questions based on their First Amendment right to free speech and their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. The subcommittee’s chairman, Republican Senator Rob Portman of Ohio, indicated that he and the ranking Democrat, Senator Claire McCaskill of Missouri, were considering referring the Backpage case to the U.S. Department of Justice and state attorneys general across America for possible prosecution.

Portman and McCaskill were steamed because Backpage and Ferrer had, in the view of the subcommittee, previously refused to comply with a subpoena ordering the release of internal company records, and Ferrer was a no-show at a PSI hearing in November 2015, where he’d been subpoenaed to attend. In statements recently published on Backpage’s site, Backpage asserts that it had been complying with the subcommittee and that Ferrer could not appear in 2015 because he was traveling outside the country.

Indeed, he may have been. Though Backpage is based in Dallas, where Ferrer resides, it is at least nominally owned by a Dutch corporation headquartered in the Netherlands. Portman claimed during the hearing that this arrangement is actually a ruse, pointing to internal Backpage documents published by the committee, which indicate that Lacey and Larkin loaned Ferrer $600 million at 7 percent interest over five years to purchase the company.

Portman suggested that the deal was meant to hide the company’s true ownership. But seller-financed loans are not unheard of, either in real estate or in business. Given the risk of such transactions for the lender, they normally come with contractual strings, so the lenders can make sure they get their money back.

In any case, in March 2016, at the prompting of Portman and McCaskill, the full Senate voted 96-0 to sue Backpage over the subpoenas the subcommittee had issued, taking the matter into federal court.

Backpage unsuccessfully sought a stay for the subpoenas, and the company had to hand over hundreds of thousands of pages in documents, in addition to thousands it had already surrendered. Though litigation over the subpoenas continues, Lacey, Larkin, Ferrer, and the others were forced to appear before the committee on a recent gray day in D.C.

Like Lacey, Larkin, and the others, Backpage co-founder and CEO Carl Ferrer invoked his rights under the First and Fifth amendments.

Not unlike in 2007, when Thomas and Arpaio stacked the legal deck against Lacey and Larkin, the Senate subcommittee was out for blood. In the run-up to the hearing, it signaled its intention to rake the Backpage honchos over the coals with a scorcher of a title for the event: “Backpage.com’s Knowing Facilitation of Online Sex Trafficking,” also the title of a 50-page report by PSI’s staff.

To the uninitiated eye, the allegations in that subcommittee report may seem shocking, though much of it had been published previously in court filings and by the PSI itself.

The report’s primary claim is that, over a number of years, Backpage had used software and teams of monitors to delete or edit ads that used a variety of forbidden words and phrases possibly indicative of illegal behavior, such as sex for money or underage prostitution.

The report fixates on the latter, offering such examples as “Lolita,” “teen,” “fresh,” “Amber Alert,” and “schoolgirl,” though Backpage’s banned word list was extensive, with as many as 120 words and phrases in 2012, according to documents offered in the report’s 840-page appendix. These included terms such as “anal,” “pussy,” “backdoor,” “full-service,” and “golden shower,” among others.

Backpage’s practices evolved over time, the report states. Sometimes entire ads were deleted because of forbidden words. Later, moderators were encouraged to edit out the terms and publish the ad anyway.

Eventually, Backpage programmed its system so that if a potential advertiser used a flagged word, the customer would get an error message, informing the user that the term was not allowed. Also, if an advertiser entered an age 17 or below, the user would get the message, “Oops! Sorry, the ad poster must be over 18 years of age.”

Such editing is offered as evidence that Backpage execs knew that illegal sex acts including child sex trafficking were being advertised on the site. Through such editing, the report argues, Backpage was “sanitizing” its adult ads, concealing evidence of criminality, and facilitating online prostitution and child sex trafficking. The report quotes an unnamed former moderator for Backpage as describing the process as “putting lipstick on a pig.”

On January 9, the U.S. Supreme Court let stand a First U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decision, upholding Section 230's protections and Backpage's right to exist.

tweet this

The Senate document also uses Backpage’s regular reports of suspicious posts to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children — a nonprofit organization authorized by Congress to be an information clearinghouse for law enforcement on child sex trafficking — as proof of Backpage’s wrongdoing.

“The Subcommittee’s investigation reveals that Backpage clearly understands that a substantial amount of child sex trafficking takes place on its website,” the report reads. “Backpage itself reports cases of suspected child exploitation to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children; in some months Backpage has transmitted hundreds of such reports to NCMEC.”

The PSI document quotes NCMEC as maintaining that “73% of the suspected child trafficking reports it receives from the public involve Backpage.”

While the subcommittee sees proof of criminal intent in the edited ads and reports to NCMEC, Backpage views these as good corporate citizenship. The report’s appendix shows that Backpage is responsive to pressure from the public and press. Documents published in the appendix indicate that Ferrer worked closely with law enforcement at times, responding to their subpoenas about Backpage ads and even offering training to law enforcement on how to spot questionable content.

If a law enforcement official asked Backpage to remove an offending image, it complied, according to company documents in the report appendix. Ferrer himself received a 2011 commendation for his assistance from the FBI, and in documents Backpage has offered online, it lists several e-mailed attaboys to Backpage from law enforcement.

Ironically, it was an investigator at the human trafficking unit of the Texas Attorney General’s Office who was responsible for alerting Ferrer to what would become a new forbidden phrase: “Amber Alert.” In a 2011 e-mail, published in the appendix, Ferrer responds at length to the law enforcement officer.

“This is either a horrible marketing ploy or some kind of bizarre new code word for an under aged person,” Ferrer writes. “I instructed my engineers to [add] ‘Amber Alert’ in any adult posting to be on our forbidden list of terms. And I will have my moderators review any existing postings with this term and possible [sic] send out NCMEC reports.”

Still, PSI’s report paints Backpage’s actions in a sinister light. Even when it did comply with a law-enforcement subpoena, it did not do so completely, according to the report, and did not turn over vital metadata or original posts, before editing. The report also offers an unsubstantiated claim from a former Backpage employee that some Backpage workers sampled the wares of prostitutes who advertised on the site.

Overall, the report gave subcommittee members plenty of ammo with which to berate the five current and former Backpage bigshots appearing before them on January 10 for a bit of kabuki.

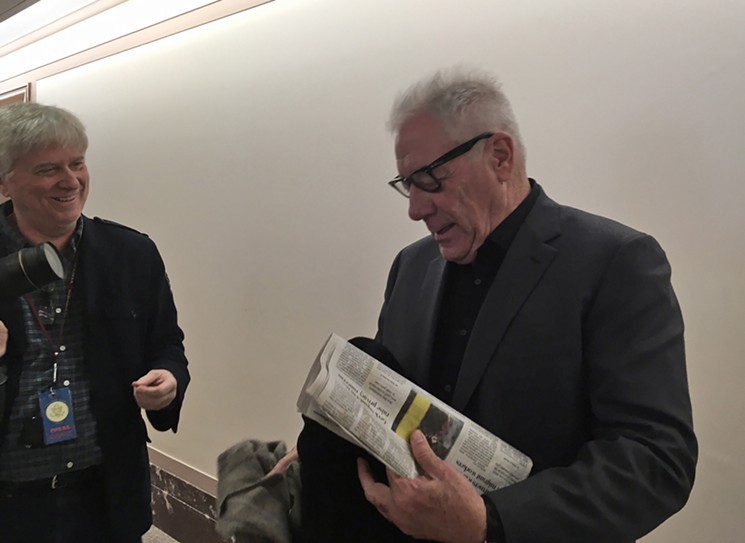

Lacey jousts with reporters following his appearance before a Senate subcommittee investigating Backpage.

Stephen Lemons

A scrum of journalists trained their cameras on the quintet, who would have looked more at home in a boardroom. Before being able to invoke their rights and exit stage left, the four men and one woman had to sit quietly and listen to these senatorial blowhards blow.

Portman crowed about Backpage’s shutdown of its adult section. “Backpage has not denied a word of these findings,” he said at the outset. “Instead, several hours after the report was issued yesterday afternoon, the company announced the closure of its adult section, claiming ‘censorship.’ But that’s not censorship, that’s validation of our findings.”

McCaskill, in her opening remarks, cast Backpage as “the market leader in selling sex online.” She then tried to clarify her point, insisting that Backpage is “a $600 million company built on selling sex, including sex with children,” a seemingly deliberate conflation of sex between consenting adults, prostitution, and child sex trafficking, a theme that persisted as the senators droned on.

At one point, McCaskill called Backpage’s policies “the definition of evil” and claimed that children were being sold into sex slavery via Backpage.

Republican Senator Steve Daines of Montana picked up on the slavery theme, offering as inspiration for the subcommittee the example of 18th-century English abolitionist William Wilberforce and the hymn “Amazing Grace,” written by a former slave trader.

Also on the dais was none other than the newly elected U.S. senator from California, Kamala Harris. She’s not a member of the subcommittee, per se, but instead was recently assigned a seat on PSI’s parent, the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee. Previously, the PSI had praised Harris’ prosecutorial zeal in pursuing Lacey, Larkin, and Ferrer.

“To be clear, this is a crime,” Harris said of Backpage’s actions in running its adult section. “It is a crime that is rightly punishable by incarceration in prison, because of the nature of the harm to the victims and the outrageousness of the conduct that is predatory in nature.”

The panel of five Backpage witnesses was then sworn in by Portman, who advised them that they were free to invoke the Fifth Amendment, but warned that if they responded to any of the questions put to them, the subcommittee would consider that right waived.

"To be clear, this is a crime … that is rightly punishable by incarceration in prison."— U.S. Senator Kamala Harris on Backpage's business practices.

tweet this

Portman and McCaskill did the questioning. At one point, Portman tried to trip up Ferrer by asking him to read a word from the list of Backpage’s verboten terms.

Ferrer paused, then replied as all of the witnesses did to the senators’ questions, with little variation:

“After consulting with counsel, I decline to answer your question based on the rights provided by the First and Fifth amendments.”

As each witness recited this, Lacey often gazed toward the ceiling. Larkin added a subtle stroke of rebelliousness by emphasizing the words “First Amendment” each time he spoke them.

Having absorbed their Senate shellacking, the five witnesses were dismissed. In the corridor outside the hearing room, Lacey bantered briefly with reporters as he made his way to the elevator, though he was proscribed by his attorneys from granting formal interviews.

When I asked his opinion on the hearing’s purpose, given that the subcommittee was fully aware he and the others would invoke their right not to speak, he smiled.

“Shame. Public shaming,” Lacey replied, adding, “What they don’t know is that I’m beyond shame.”

In the hubbub of the hearing and the aftermath of Backpage’s closing of its adult section, it was lost on most present that, also on January 9, the U.S. Supreme Court handed Backpage yet another win in federal court by denying an appeal of a 2016 ruling by the First U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals that upheld Section 230’s protections and Backpage’s right to exist.

Writing for the three-judge appeals court panel, Judge Bruce Selya laid out many of the arguments proffered by the subcommittee in its report and during the hearing. The suit was brought by three young women who, according to Selya, were trafficked on Backpage from 2010 to at least 2013 while underage and raped thousands of times.

The plaintiffs’ lawyers argued that because Backpage had censored certain forbidden words before publishing the ad, stripped metadata from accompanying photos, and accepted anonymous payments, it had forfeited its immunity under Section 230, which plainly states that “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker” of third-party content.

But the appeals court disagreed, referring to the law’s so-called “safe harbor” provision, which says that website owners cannot be held liable for “any action taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material” that the owner finds objectionable for any number of reasons, such as obscenity, lewdness, violence, and so on.

Congress had done this, writes Selya, in an effort to foster the growth of the internet and so that providers of online message boards, say, or newspaper comment sections, could not be sued for defamation because of something posted by a third party.

Through Section 230, Selya observes, “Congress sought to encourage websites to make efforts to screen content without fear of liability.”

Selya’s conclusion that Section 230 shields Backpage from state prosecution or civil liability is, by this time, black-letter law. Judges for the Ninth, Seventh, and other appeals court circuits have ruled similarly, and the U.S. Supreme Court has declined to review them. In fact, when Harris brought state criminal charges against Lacey, Larkin, and Ferrer last year, justifying that prosecution, in part, on the grounds that Backpage edited out words indicative of illicit sex, Bowman shot it down for similar reasons.

Responding to the claim from the AG that Backpage had edited and reposted its escort ads to other websites to make them more palatable, Bowman commented in his decision that the prosecution essentially was claiming that Backpage modified content to go from illegal to legal.

“Surely the AG is not seeking to hold Defendants liable for posting a legal ad,” wrote Bowman. “This behavior is exactly the type of ‘good Samaritan’ behavior that the CDA encourages through the grant of immunity.”

It’s no wonder that Silicon Valley is paying close attention to Backpage’s struggles over Section 230. Without that protection, Twitter could be held liable for supporting terrorists because of tweets made by followers of ISIS. Mark Zuckerberg could be sued for a libelous statement made on a user’s Facebook page. And various criminal acts — from fraud to murder — could rebound on Google if someone used Google Plus to plot them.

A screenshot from Backpage.com's Phoenix site on the evening of Monday, January 9, 2017.

Backpage.com screenshot

Yet there is another possibility when it comes to Backpage: federal criminal prosecution. In 2015, in an attempt to get around Section 230 and go after Backpage, Congress passed the Stop Advertising Victims of Exploitation Act, or SAVE Act, which makes it a crime to knowingly disseminate advertising that involves commercial sex acts or the sex trafficking of children or adults.

After it was passed, Backpage sued the government, seeking to invalidate the new law. The company lost, but according to Eric Goldman, a law professor with Santa Clara University and the co-director of that school’s High-Tech Law Institute, the listings leviathan scored a key interpretation of the law by the judge in Backpage v. Lynch, which establishes a higher level of what lawyers call scienter, or knowledge of wrongdoing, for publishers.

“In that case, the court laid out some really important parameters about the First Amendment limits of the SAVE Act,” Goldman says. “And those First Amendment limits are going to make it difficult, if not impossible, for the DOJ to win, if they ever choose to enforce the SAVE Act.”

But will Donald Trump’s presumptive U.S. attorney general, Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions, who has indicated that obscenity cases might be revved up under his tenure, go after Backpage if Portman and McCaskill forward the subcommittee’s report to him for further investigation?

“It wouldn’t surprise me if the DOJ decides it’s just not worth it,” says Goldman, who writes a go-to blog on law that affects the internet and tech companies.

Yet he admits that if Sessions goes after obscenity, he may also decide to go after ads offering sex services as well. Meanwhile, the online marketplace for such services continues.

Some of the escort ads on Backpage have already migrated to its personals section, just as happened on Craigslist when it eighty-sixed its adult section. And other, more direct websites, such as Eros.com, can expect a boost in business.

Advocates for sex workers say Backpage’s decision will scatter those who advertised on the site’s adult section, perhaps into the encrypted nether regions of the dark web, where law enforcement will have difficulty identifying child sex trafficking victims.

But for Goldman, the most worrisome aspect of Backpage’s decision is the bad precedent it sets. “We have court rulings that Backpage is legal, and yet Backpage has exited the industry because of pressure placed on it by government actors,” he says.

“Whether we call that censorship or not, we should be extremely nervous that our government can [do this],” he adds. “That’s not an online prostitution ad problem. That’s a rule-of-law problem.”

E-mail [email protected].