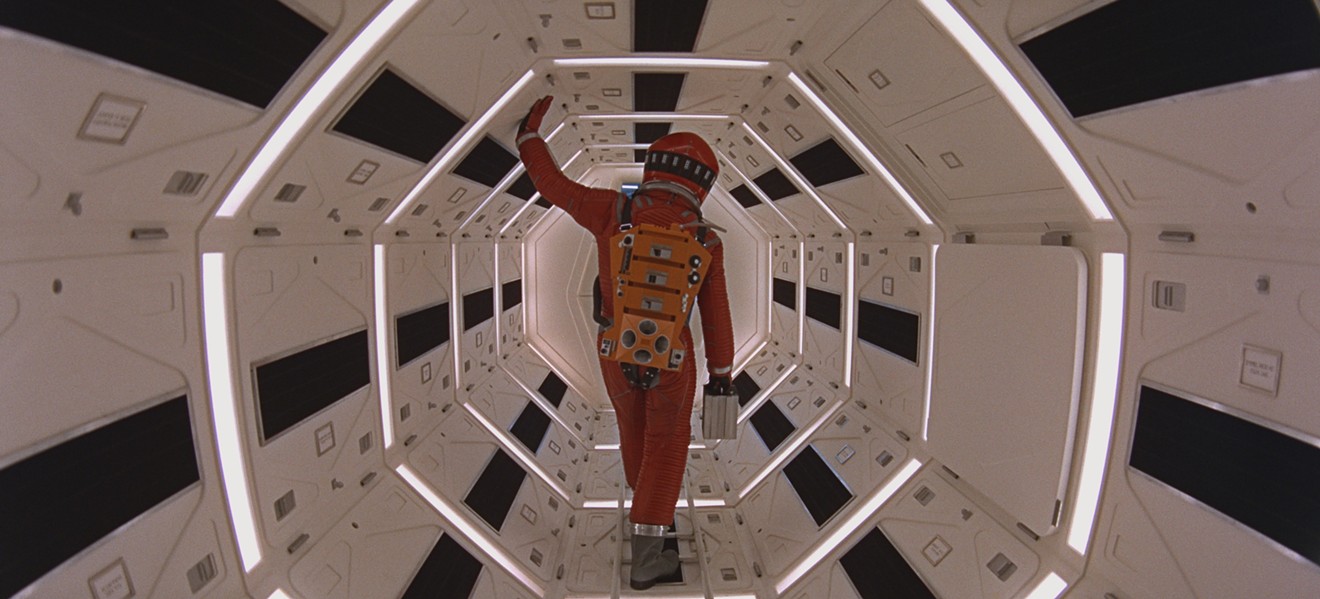

One of the hottest tickets at Cannes this year was for a 50-year-old movie that pretty much everybody had already seen and would soon be back in release. Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film that had never screened at Cannes, made by a director who had never come to Cannes, arrived here courtesy of Christopher Nolan, who had also never shown a film at Cannes. Billed as an “unrestored” 70 mm print — that is to say, a new print without any digital restorations or alterations — the film screened at the great Debussy theater, because it was one of the few places that had the proper speaker arrangement to do true justice to the soundtrack of the movie’s 1968 Cinerama presentation. Nolan was accompanied to the premiere by Kubrick’s daughter, Katharina Kubrick; Kubrick’s producer and brother-in-law, Jan Harlan; and Keir Dullea, the actor who played astronaut David Bowman, the biggest human role in the film. The massive standing ovation after the screening was a foregone conclusion, but it was still heartwarming to see the love in the room for one of Kubrick’s greatest masterpieces. (The Nolan version of the film is now opening throughout the country.)

Cannes has never been big on science fiction, especially science-fiction studio blockbusters. (They do sometimes make exceptions; Solo: A Star Wars Story played the festival this year.) In a way, though, is the ideal Cannes film, in how it straddles art and mainstream cinema, austerity and magnificence, personal vision and commerce. It’s still stunning to me that the film was such a hit back in its day, given the bizarre, unorthodox quality of its narrative. The story unfolds via silent suggestion, and the seeming coldness of its surfaces is purposeful, conveying humanity’s complicated relationship to its tools: The primates of the first section live in a world without tools, and thus don’t know what to make of them; the future humans of the later sections live at the mercy of their tools, and thus don’t question them — until, finally, they do. Thus, alienation is the central thrust of 2001: alienation as ignorance, and alienation as detachment. This was one of the many reasons that the Village Voice’s Andrew Sarris, never a big fan of Kubrick’s, initially hated the film; to him, it was “Antoni-ennui” in disguise. (To his credit, Sarris later revisited 2001, this time making sure to get stoned beforehand, and decided it was an important and personal film from a major artist.)

It occurs to me that I’ve watched 2001 in pretty much every format imaginable: Betamax, VHS, laserdisc, DVD, Blu-ray, 16 mm, 35 mm, 70 mm, DCP, TV broadcast, cropped, uncropped, standing up, sitting down, lying down, with the lights on and people screaming, in a perfectly quiet movie theater with only me and three others. … I was, I think, 5 when I first saw it; Star Wars buzz had hit Ankara, Turkey, but not Star Wars itself, so my parents took me to a screening of 2001 telling me it was Star Wars. (Imagine thinking for a whole year or so that 2001 was Star Wars.) 2001 did have a cursory 70 mm theatrical re-release in 2001. Kubrick had died and the Warner honchos that worked with him had departed, so the release, which I suspect had been negotiated before the filmmaker’s death, came with little advertisement or support from the studio.

Sometimes people tell you that a movie becomes an entirely different thing when you actually see it on a huge screen. (I am often one of these people.) Often, they’re (we’re) exaggerating; the movie may play better, and you may watch better, but what’s actually onscreen rarely changes. 2001, however, is a different thing. It’s a film made for that huge screen, for absolute immersion. There are fine details in the image that are nearly impossible to see on a TV. The level of obsessive minutiae that Kubrick and his fellow wizards put into every shot is bewildering: Watch the scene of the spaceship docking at Clavius Base; on a big screen, you can see that there are tiny people doing tiny activities in each of the tiny windows, with tiny little monitors behind them, each showing different tiny little things. It was maybe on my 10th viewing of the film that I finally caught that.

And time moves differently in 70 mm: What drags on a small screen becomes immersion in an actual environment on a huge one. With TV, you wait for something to happen. With 70 mm, you are the thing that’s happening; you’re living in the space of the film, at least for a little while. That’s why the “space” in that title has different meanings: The film is a journey through outer space, but it is also a journey through cinematic space. It conjures the future by making you sit through its vision of the future, spending time just being in it. A sense of scale and spectacle is crucial to 2001, because it contrasts with the blase attitude of the humans in the film; the tension between our awe as viewers and their indifference as characters is what the film is largely about.

Watching 2001 in 70 mm, I was also struck by how differently the celebrated Stargate sequence at the end of the film — the giant, trippy light show that basically obsessed a generation of viewers and helped turn 2001 into the ultimate stoner movie — plays on a massive screen. The rumbling and howling on the soundtrack, the floor shaking beneath your feet, the blossoming colors and speeding rays of light, the wild patterns forming and reforming on the screen, the occasional freeze-frames back to David Bowman’s face — at that size, these things actually do cause some physiological reactions. I felt not only transported, but as if my body had suddenly stopped being my own for a few minutes; as if the film had taken over. By restoring our sense of awe, 2001 doesn’t just command our attention on the screen — it sends us out of the theater to see the world with new eyes.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]