Canyon Mine, owned by Energy Fuels Resources, is about 12 miles from the south entrance to Grand Canyon National Park. Despite decades of opposition to the mine, its grandfathered mineral rights so far have exempted it from a 20-year ban on new mining around Grand Canyon that was enacted in 2012.

As several of Arizona’s Democratic lawmakers have sought this week to make the 20-year ban permanent, the lengthy battle over Canyon Mine continues to highlight the challenge of convincing authorities to close any part of Arizona to mining.

The lawmakers' efforts follow a long history of people protesting mining near Grand Canyon and warning of permanent damage to the environment, to water, and to the heritage of indigenous peoples.

Last fall, more than 1,500 Arizonans submitted comments — most of them copies of a form letter, others highly personalized pleas — to the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, which has issued the permits that Energy Fuels Resources needs to keep up its exploratory operations. And some comments are still trickling in.

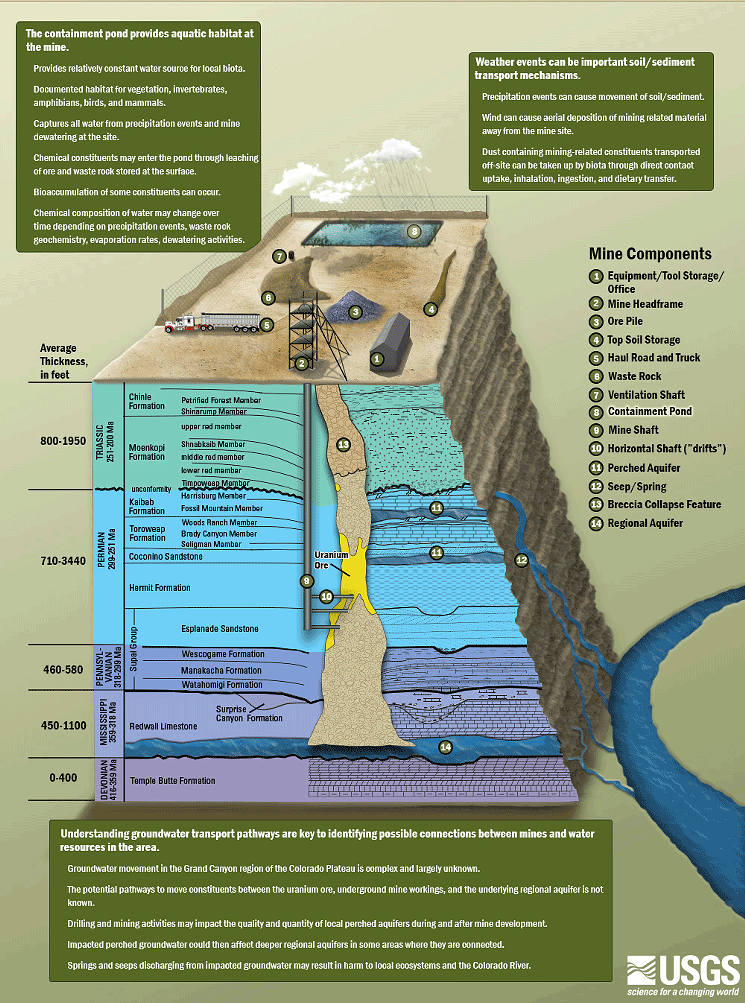

Those comments, hundreds of which Phoenix New Times has been obtaining over recent months through a public records request, begged ADEQ not to reissue a crucial groundwater permit and to close the mine for good. Primarily, they cited concerns about groundwater contamination including how exploratory mineshafts have pierced perched aquifers and how radioactive water could be discharged into deeper aquifers that feed the seeps and springs of Grand Canyon.

“I beseech you: stop the flooding and close Grand Canyon Uranium Mine!” one person wrote. “DO YOUR JOB,” wrote another.

“I’m all for America’s energy and security independence but as a private boater whose [sic] rafted Grand Canyon and seen the fragile ecosystems that exist in that ditch and the diversity of peoples that depend on the Canyon’s resources day to day to survive, I have to say, the Canyon Uranium Mine was and is a bad idea,” one commenter said. “It’s just a disaster waiting to happen.”

Some who sent form letters topped them off with their own thoughts.

“The boilerplate text below doesn’t begin to express how dismayed I am to hear about this. Grand Canyon is an international treasure that we Americans have the unique privilege to act as stewards for, and that stewardship must be done right or this treasure will be damaged forever,” one person wrote. “There is no way to fix this sort of damage once it’s done."

State Considers Permit

Those pleas, so far, have fallen on deaf ears at the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, which has maintained that it is required to issue or renew a permit if legal requirements are met.“ADEQ is reviewing available information to make a science- and data-based decision regarding the permit coverage of Canyon Mine,” agency director Misael Cabrera wrote in September in response to a letter sent by the Sierra Club, the Center for Biological Diversity, and other local conservation groups calling on the department not to reissue the permit and to close the mine altogether.

Those groups had warned that close to 10 million gallons of groundwater that seeped into the mine in 2018 had high levels of uranium that, together, “threaten irretrievable harm to perched and deep aquifers and their associated human and environmental values.”

“The U.S. Forest Service and ADEQ have for decades assumed that Canyon Mine poses no significant risk to groundwater,” they wrote. “Groundwater flooding at the mine, which is ongoing, now belies that assumption and ADEQ’s coverage of the Canyon Mine under a general [Aquifer Protection Permit].”

To date, ADEQ has not yet decided whether to renew the permit, and until it makes a decision, the existing permit remains in effect. Erin Jordan, spokesperson for ADEQ, said she did not have an estimate of when ADEQ would make its decision.

According to Energy Fuels Resources, Canyon Mine contains some 2.43 million pounds of uranium ore that could be winnowed down to 130,000 pounds of uranium. The ore would be hauled 270 to 320 miles to White Mesa Mill in Blanding, Utah, for milling.

Uranium mining could have a profound and irreversible impact on the region’s water.

U.S. Geological Survey

Stops and Starts

The property was bought in 1982, when exploratory drilling and construction began. But starting in 1987, when uranium prices fell, the mine was put on standby, remaining that way until 2013, when it began extending its mining shaft only to pause again because of low uranium prices.In 2015, things started again, and Energy Fuels Resources began drilling down farther.

“As of the effective date of this report, Energy Fuels and its predecessors have completed a total of 150 holes ... totaling 92,724 ft. from 1978 to 2017,” said a report that Energy Fuels Resources commissioned in 2017. “Since 2016, Energy Fuels completed 105 underground drill holes totaling 30,314 ft. on the Property.”

According to Energy Fuels Resources, restoring the mine area to its pre-mining state will cost just $500,000.

“At the conclusion of underground operations, mine openings will be sealed with development rock being used for backfill, infrastructure will be dismantled and removed, buildings demolished, and other surface features, such as roads and ponds, reclaimed in place,” that report said. “Areas of disturbance will be contoured to blend with the existing landscape and re-vegetated with a native seed mix.”

That report acknowledged that “the Mine has been particularly contentious among local communities” due to its proximity to the Grand Canyon and “claims by the Havasupai Indian Tribe that the Mine site has significant religious value.” Its location within the area withdrawn from mining in 2012 has also rendered it controversial.

The mine has been wrapped in extensive litigation for decades, starting in the late 1980s, when entities including the Havasupai Tribe sued the U.S. Forest Service for allowing the mine to proceed. Appeals wended their way through district and appellate courts until the mine was put on hold when uranium prices fell.

In March 2013, the Center for Biological Diversity, the Grand Canyon Trust, the Sierra Club, and the Havasupai Tribe sued the Forest Service again, seeking an injunction and an order that the Forest Service had failed to comply with the law in allowing Canyon Mine to go forward.

Two years later, a district court ruled in favor of the company, and the groups appealed. In 2018, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals remanded the case back to Arizona District Court, saying it needed to review the case under a different federal law than the one it had used, and the case is still pending.

Although the federal government has said the Canyon Mine has a valid right to mine uranium, those groups disagree, explained Taylor McKinnon, senior public lands campaigner with the Center for Biological Diversity. "Our lawsuit says there’s a whole suite of costs that weren’t considered," he said.

What the court decides will affect the fate of the mine. If it declares that Canyon Mine doesn't have a valid right in the area, it will be included in the 20-year mining moratorium and could be subject to a proposed permanent ban on mining around the Grand Canyon.

Permanent Ban Still Possible

Congressmen Raul Grijalva and Tom O’Halleran introduced legislation for such a permanent mining ban last October in the House, and in December, Senator Kyrsten Sinema did the same in the Senate.This week, one particular Arizona lawmaker, Republican Senator Martha McSally, who has yet to take a stance on the bill, came under more pressure to protect the lands around Grand Canyon from destructive uranium mining.

The National Congress of American Indians sent a letter on Monday to Arizona’s Republican Senator Martha McSally, urging her to co-sponsor Sinema’s bill.

“The National Congress of American Indians strongly opposes any actions that would potentially harm the vital water resources in and around Grand Canyon,” the group’s CEO, Kevin Allis, said in the letter. “Tribal nations have relied on the surface water and groundwater resources in the Upper Colorado River Basin for millennia, way before the United States granted Grand Canyon federal protections as a National Park.”

“Tribal homelands were intended to provide a permanent homeland for present and future generations,” Allis added. “This necessarily includes protecting our natural and cultural heritage resources from the unnecessary contamination often associated with mining activities.”