When the sun burns the humidity out of the sky and extreme dry heat starts to push the mercury up to ludicrous levels, that's when "Grandpa Jim" Fowler knows it's time for his annual goal to hike to the summit of Camelback Mountain on the hottest afternoon of the year.

To make it happen, he and a group of about 10 friends and family members have to try several times each summer. If they've already hiked it when it's 114 and a couple of weeks later the weather service is calling for 117, they have to get out there again. They've been doing this for more than 10 years, Fowler said.

"We started doing it because, uh — there's no good reason," he admitted.

He and family members are avid runners as well as hikers, and they run on hot days, too. Fowler enjoys hiking in the heat. He feels he's acclimated to it. It makes running on the cooler days feel easier.

Chian Ma of Scottsdale also loves the heat. He's outside trail-running every day of the year, no matter how hot. He's also got his traditions: In the past few years, he and fellow hikers have hiked Camelback at 3 p.m. on Father's Day, which in late June is an almost-guaranteed scorcher in Phoenix.

"It doesn't bother us," he said of the heat. "Maybe we'll crack open a beer."

Fowler and Ma are just two of the local hikers who see a Phoenix "pilot program" of trail restrictions on ultra-hot days as a major infringement on their chosen activity.

The program was put into place on July 13 by a 4-2 vote of the Phoenix Parks and Recreation board, but a ban hasn't been triggered yet due to recent monsoon storms that mellowed the daytime heat.

But here's how it will work: From now until September 30, the city will close the summit trails of the Valley's most popular mountains, Camelback Mountain and Piestewa Peak, from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. on "excessive heat watch" days. Park staff will close the parking lots and anyone caught on the trails during those times may risk a citation.

Yet the level at which it's too hot to hike varies greatly among individuals, and the ban wasn't based on when most hiker heat emergencies have occurred. The United Phoenix Firefighters Association Local 493, which pushed for a hot-trail ban, originally wanted the trails closed anytime the temperature got over 105 degrees. The union would be open to expanding the restrictions, a spokesperson told Phoenix New Times.

Extreme hikers like Fowler and Ma would prefer the city to retrain its firefighters or park rangers instead of continuing the pilot program next summer.

"I do feel for them, when you have to bring all that gear," Ma said of the firefighters. "It is a tough job. I want to see less rescues."

But, he added, it's "nonsense" to ban hikers during periods of excessive heat.

"What's excessive?" he said.

Hot-Trail Ban

The extreme hikers say they realize there's a problem. Because they run the trails regularly in the heat, they often encounter people suffering from heat exhaustion on Camelback and Piestewa. The mountains, which rise about five miles apart from each other, are not twins in appearance but offer similarly tough summit trails; each gains about 1,200 feet of elevation — roughly the same height as the Empire State Building — over the course of less than 1.5 miles. Unprepared hikers may believe that the round trip of less than three miles will be a cinch. They don't bring enough water and keep going up when they should be bailing out.Statistics show that in 2018 and 2019, the number of rescues on Camelback Mountain alone was nearly double what it was from 2009-2012, going from about 50 a year to 90. The city says that roughly half of all Phoenix mountain rescues occur on either Camelback or Piestewa, but the mountains are extremely popular and are the locations of an estimated 20 percent of all the hikes that occur in the city.

The sudden change in city policy this summer followed a series of back-to-back mountain rescues on the two trails on June 16, a day that the high temperature reached 116. Twelve members of the fire department's technical rescue team (TRT) had to be sent home; two were reportedly hospitalized with temporary kidney failure. That spurred the firefighters union to send an urgent letter to city officials requesting trail closures.

An excessive heat watch had been declared for that week. But recently, on July 15, Phoenix firefighters responded to a total of four mountain rescues before 3 p.m., including two heat-related emergencies on Camelback and one on Piestewa Peak that involved a dehydrated woman who took a fall. The high temperature for that day was 102 and no heat watch was in effect.

One of the rescues involved a family of five from another state who had been hiking on Camelback for several hours. Phoenix Fire Department Captain Douglas Scott acknowledged that most of the people who require heat-related rescues are not from Arizona — he estimated that the ratio might be as high as two-thirds out-of-towners, who aren't as acclimated to Phoenix's desert heat. But another victim in the July 15 rescues was a 33-year-old local man.

"It's been brutal for even consistent hikers," Douglas said.

As a July 17 opinion article by Abe Kwok of the Arizona Republic pointed out, statistics don't actually show that closing trails on hot days would mean fewer rescue calls. About half the calls in any given year occur in the cooler half of the year, and this year, 82 percent of the rescue calls came when the high was less than 105 degrees.

The stats don't break down the rescues by type and don't specify which are heat-related. A fire department official told New Times the data is being analyzed so Parks officials and the public will have more information about the pilot program.

Heat Risk

Caring about heat risk has been an evolving process in Arizona and the rest of the United States. The National Weather Service didn't always have an excessive heat watch program, but over time, people realized that heat was having an impact on communities, said Paul Iniguez, a science and operations officer for the NWS. Plus, temperatures have been rising over the years — especially the overnight lows that play a significant role in heat deaths."Every day, people are suffering some kind of heat illness," Iniguez said. "Part of our process as an agency is to provide this weather information."

Once the NWS issues its advisories, it's up to people to do what they want with the information, he said.

A heat watch means there's a 50 percent chance of excessive heat for the days in question; the "watch" is upgraded to a "warning" when the NWS has 90 percent confidence in its prediction.

But "excessive" means something different in Phoenix, where residents can count on a heatwave every summer. For most of the country, a heat watch is declared because of the chance that the heat index, a measure of temperature and humidity, will rise to 105 or higher for at least two consecutive days. In 2001, the Phoenix NWS office began using a different system based on an algorithm that instead identifies "oppressive" air masses that have known ties to heat deaths.

While some parts of the country can have dangerously muggy weather, the "most dangerous air mass" for metro Phoenix in terms of heat-related deaths is an "extreme form of dT (dry tropical)" with above-average temperatures and below-normal dew points, according to a 2006 research paper by Doug Green, a retired NWS science and operations officer.

Phoenix forecasters feed their system with data including hourly temperature, clouds, and humidity; they also take predicted raw temperatures into account. If "the most dangerous air mass exists" and the maximum predicted temperature meets or exceeds 99 percent of all past high temperatures in Phoenix, a heat watch or warning is issued, as Green describes. For July 16-29, for example, the 99th percent maximum temperature is 114 degrees, he writes.

The NWS also considers the time of year in declaring heat watches. In April, a heat watch was in effect for a day that was only expected to reach 102. Early-season heat can be dangerous even at lower temperatures, because people haven't had a chance to acclimate. No heat watch would be declared between now and September 30 for a temperature as low as 102, but may be called for less than what a local hiker might call "extreme."

If wind or rain looks promising, a heat watch could be canceled. But that doesn't mean it will suddenly be safe enough for everyone to hike. Even on heat watch days when the new trail ban is in effect, the gates won't close until 11 a.m. Many, if not most hikers, would start earlier than that, especially on a hot day, and could still easily run into a problem if they stay on the trail for hours or find themselves on the summit at 11 a.m. without enough energy to get down.

One secret of the extreme hikers is that they're up and down the mountain quickly. Often, the people rescued on Piestewa and Camelback were on the trail for four or five hours — far longer than the 1-2 hours it takes a fit hiker to make a round trip to the summit.

"If I was out there for five-six hours, I'd be in the same situation," Ma said.

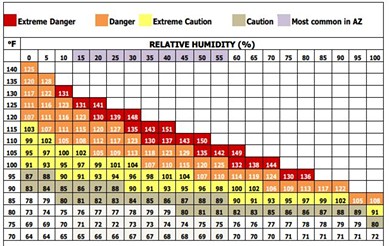

Humidity also plays a still-unknown role in the number of Phoenix mountain rescues. With 15 percent humidity, the extreme temperature of 110 is reduced to a heat index of 108, which may feel a little better to a sweaty hiker. Conversely, the same person may find a slightly cooler day with higher humidity more taxing.

People exercising outdoors for a prolonged time have a higher risk of heatstroke when the heat index is 105 or higher, health experts say. When it's 100 in Phoenix, the heat index could be 107 — maybe too hot to go on a strenuous hike?

Looking at a heat index chart, someone from Florida might be forgiven for thinking people who live in Phoenix are nuts. After all, it routinely gets to 110 or higher here, and with 50 percent humidity, that would mean a devastating heat index temperature of 150. But Phoenix has never reached anywhere near that high, so far.

"Even on the 122 day [in 1990, Phoenix's hottest recorded temperature], we didn't get to 125 heat index," Iniguez said.

'Hike Smart'

In June, Michelle Meder, a religious teacher from Ohio, was hiking in Grand Canyon with her husband and two adult children down Hermit Trail, starting a multi-day trip across the desolate Tonto Trail. The shade temperature was 115 in the inner canyon that day, but there is little shade on the steep Hermit Trail. Meder reportedly began suffering from heat exhaustion on the first day. Her family called for help the next morning. Rangers were dispatched, but were too late to save her life.Rangers find miserable hikers withering from the heat every summer day in the Canyon, according to the National Park Service. The weather service calls several heat warnings a year for Grand Canyon, usually applying only to areas below 4,000 feet. It's about halfway down from the rim to the inner canyon, where summer temperatures often equal those of Phoenix. But the federal government, which runs the park, doesn't close the canyon's trails for blizzards or extreme heat.

The National Park Service does alert visitors to the danger, warning people not to venture below the rim on days of extreme heat. Hikers can't miss the signs placed on various trails with a depiction of a man vomiting in the heat. But it's up to park visitors to know their limits.

"We're constantly trying to advise the public it's not Disneyworld when you go to the Grand Canyon," said Joelle Baird, park spokesperson. "It's a very inhospitable environment."

Yet the park balances the warning messages with the notion that Grand Canyon is open and accessible, and officials want to "empower" people to explore it, she said. The park does close trails occasionally, but it's for maintenance or because of "major rockfall." Trails in the inner canyon aren't closed during periods of extreme heat "because we feel there is a way to hike smart, and implement safe hiking principals," Baird said.

Visitors can be "successful" hiking even on heat-warning days if they take the steps to reduce heat illness, she said.

The National Park Service website has numerous tips on the heat that could apply to Phoenix hikers, and also points out that rescue efforts may be hampered in the summer because of "limited staff, the number of rescue calls, employee safety requirements, and limited helicopter flying capability during periods of extreme heat or inclement weather."

Grand Canyon is larger than some states, meaning rangers may be nowhere near a victim who's dying of heatstroke when time is of the essence. It's a different situation in Phoenix, where TRT team members from the Phoenix Fire Department's Station 12 are always just a few minutes from either Piestewa Peak or Camelback Mountain.

And this summer, with more unprepared hikers than ever throwing themselves like proverbial lemmings at the broiling mountain trails, local firefighters say they're being worked to unreasonable limits in life-threatening heat. They've had enough.

Restrictions Here to Stay?

The decision to push for a trail ban on hot days wasn't something the United Arizona Firefighters Association took lightly, knowing it impacts people's freedoms, said PJ Dean, a Phoenix fire captain and spokesperson for the union. It's "unusual" for the union to take such a step, but "the danger is real and it's getting worse."Dean pushed back on any claims that TRT members aren't fit and ready for rescues on the city's toughest trails, even in the heat. "Some of them are triathletes," he said. "Clearly, [critics] have no idea what kind of shape firefighters are in and what kind of efforts they undertake."

Yet Dean acknowledges that the union's executive board members, when deciding that they would recommend trail restrictions, had no scientific basis for choosing 105 degrees as the cutoff, nor does the union know if most heat emergencies occur on heat-watch days. The union could support lowering the temperature that triggers the restrictions, he said.

"We're not meteorologists," Dean said. The hope was that the parks board would adopt something, as they did, that "moved the needle" and educated the public on the severity of the problem.

"We're happy with the new pilot program," he said, calling it "a balanced approach to hopefully make it safer."

After the pilot program ends on September 30, "maybe we have to increase it, maybe we have to decrease it," he said.

In other words, the new pilot program could be a precedent for more trail restrictions in the future when it's hot, or even when — to some — it's just kind of warm.

The politically powerful union, with more than 1,600 members in Phoenix alone and several hundred more in other Valley cities, has contributed tens of thousands of dollars to city council members in recent years. The request for restrictions was praised by Phoenix council members. Even Sal DiCiccio, the nine-member body's outspoken conservative, said in a statement he fully supported the park board's hot-trail ban.

"This pilot program is a great first step, but more needs to be done," he said. "I will be strongly advocating to make this a permanent practice moving ahead."

And so, for now at least, it seems that people who want to make their own decision on when it's safe to hike will be fighting an uphill battle.