In his 2016 book Commissary Kitchen, rapper Albert ‘Prodigy’ Johnson wrote: “Food isn’t just nourishment. It’s your being. It’s your family, your memories, your neighborhood, your ethnicity, your travels, and everything in between.”

And later: “In a world where prisoners are treated like animals, we made our experience there feel more human by how we prepared our food. After all, we were somebody’s brother, somebody’s daddy, a son.”

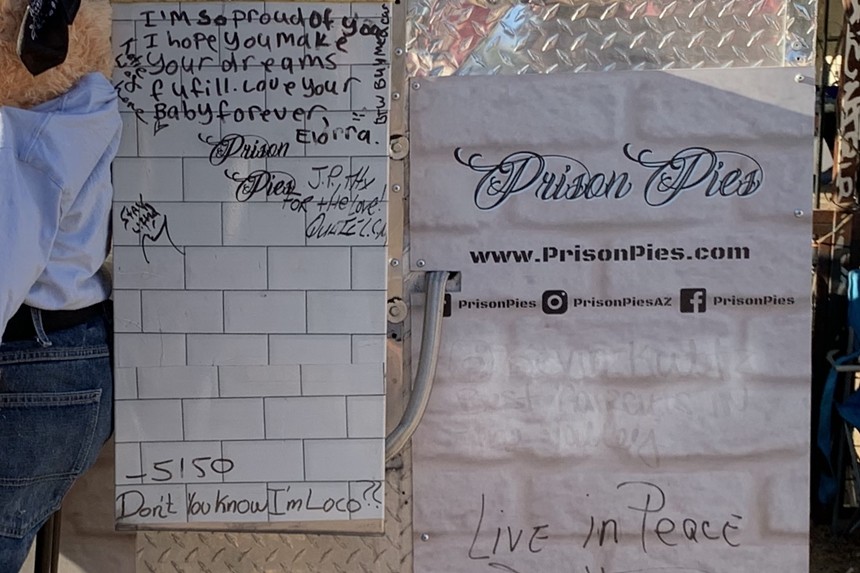

On a recent First Friday in downtown Phoenix, a small food cart at Fifth and Garfield attracts curious passersby with its name, Prison Pies. Phrases like “It’s chow time,” “Food so good it should be illegal,” and “Come try prison-inspired foods made by convicts” are written on the cart’s laminated faux-brick background. On the other side are handwritten notes, including one of encouragement from the owner's 12-year-old daughter. The menu offers Prison Tamale, Prison Nachos, Chow Hall Hot Dogs, and Cadillac Iced Coffee.

Serving a prison sentence carries a stigma, often creating barriers to employment. Prison Pies owner John Avila decided to embrace that stigma and put his past front and center. Although Avila had the idea for his food business following his release in 2004, it wasn’t until the summer of 2021 that he brought it to fruition. “Summer in Phoenix was not the best time to open, but slow days helped with the learning curve, since I had never worked in the food industry,” he says. Prison Pies merch, also for sale here, is made at his shop, Mary Jane Smokewear, a printing business he's owned since 2009.

Avila learned to cook from his grandmother and followed up later by watching cooking shows.

Last fall, at a talk in conjunction with the Arizona State University Art Museum exhibit Undoing Time: Art and Histories of Incarceration, Avila asked the audience if anyone had watched prison reality-TV shows; a few hands went up. “They always show the drama, but they never show you about our food," he told them. "Mealtime is really important to us. It’s where we come together and show each other respect. Whether it’s your birthday or you're about to be released, your homies throw you a party. And then you get your ass whupped. It’s savage, but there’s a lot of love in there, too.”

In 2020, prisons spent anywhere from 75 cents to $3.18 per meal per person. In 2015, the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization that sheds light on the criminal justice system, reported Arizona’s allowance to be 56 cents per person on average.

Prison food, of course, is not your own. “You start to miss and crave your cultural food," Avila says. In addition, the quality of prison food is dismal, leaving inmates hungry and demoralized, at times even physically ill. There have been reports of moldy bread, rat and roach infestations, and expired food.

"We'd find rocks and bugs in our food," recalls Phoenix artist and former inmate Jesse Yazzie. "The portions were so small, we were always starving.”

Moreover, research shows that many who enter a correctional facility healthy leave with diabetes and hypertension because of the high sodium, refined starch, and sugar content of the meals. A 2017 article in the American Journal of Public Health reported that inmates are 6.4 times more likely to suffer from food poisoning than the general population.

As a result, inmates started making their own food.

“The food we made ourselves was better than the chow hall’s, and I loved watching people’s reaction to it,” Avila says. He and others would purchase ingredients from the prison commissary with money received for work or good behavior.

According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, inmates can earn between 12 and 40 cents an hour for work. When Avila was incarcerated, he says, he got "a paycheck of about $14 every two weeks."

With ingredients purchased from the commissary, inmates can invent their own recipes, and often improvise to construct a semblance of foods from their heritage. There are a number of prison recipe books written by people who have served time. Convicted Cooking, Commissary Kitchen, and The Prison Gourmet are just a few of the titles out there.

“When you taste the food of your culture, you temporarily forget about the walls surrounding you, the lockdowns or fights,” explains Avila. “You think about your family and the people you're missing.”

For his part, he longed for his grandmother’s tamales. He remembered how she’d recruit the whole family to make the dish, “like an assembly line, and she was the boss.”

When he tasted the tamales his fellow prisoners made, he says, “it felt like home.” Instead of corn flour, they would crush Doritos and moisten them to create their version of masa, then top it with canned shredded beef. Avila uses the same recipe at his food cart, but now he cooks the meat himself.

Cadillac Coffee is a mocha-esque coffee with chocolate or caramel sauce and your choice of candy (Snickers, Butterfingers, all of the above). There was no chocolate sauce or sugar in the correctional facility, so inmates would crush candy bars and add them to their coffee. “This drink made us feel like we were on the outside for a little bit,” Avila remembers.

At the cart, he greets customers and takes their orders. When he overhears a customer saying that he’s a Doritos fiend, Avila adds extra Doritos to his tamale. He’s using the small chip bags in place of a corn husk or banana leaf, shaping the moistened mix of crushed chips and shredded beef by folding the bag just so. When he cuts the bag open, a rectangular tamale awaits. Get it with cheese and beans, and don’t hesitate to dig in. It has the texture of a tamale, with a meaty Doritos flavor. But the sensation goes beyond taste: You can feel Avila’s love of cooking and his joy of sharing the very meals that gave him a momentary escape — and you appreciate what he's done to get here.

Visit the website to learn more about Avila and Prison Pies' whereabouts.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]