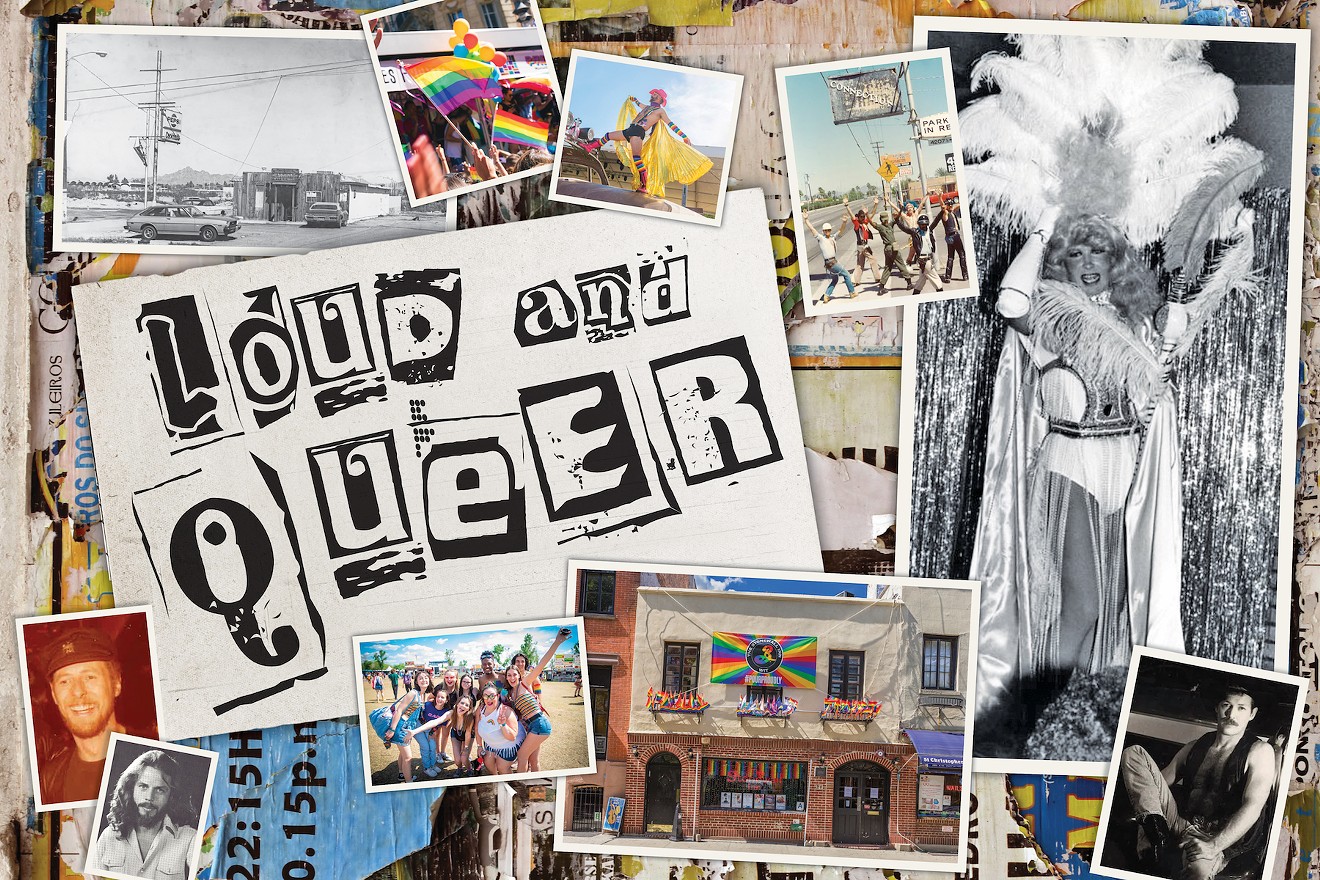

Shockwaves from the Stonewall riots were felt around the U.S., including here in Arizona, where members of the Valley’s LGBTQ community of that era were outraged for many reasons, not the least of which because they’d endured persecution by the police for their sexual orientation.

“We were shocked. We were infuriated,” Kim Moody, currently the co-owner of downtown Phoenix art space the Alwun House. “It’s one thing for them to close the place, and it’s another to be dragged out of a bar.”

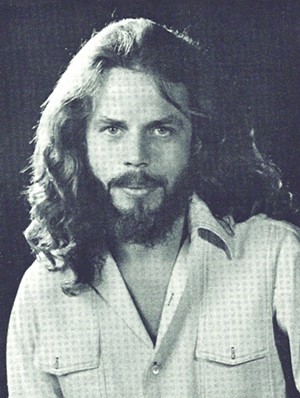

Valley resident John La Noue, who owned and managed various local LGBTQ bars in the ’70s and ’80s, remembers being just as furious. And he was ready to fight back.

“I was like, ‘Those sons of bitches.’ I would have taken out as many as I could before they took me out,” he says. “I mean, I was rowdy, I always fought back, but after I read about Stonewall, then my attitude was, ‘You can’t be doing that shit. I’m not gonna stand for it.’”

Members of the Valley’s LGBTQ community of the time were also empowered, not only to stand up for their rights but to effect change.

A lot has changed in the past 50 years. The vast and colorful bar scene that exists today is a far cry from what existed in 1969. In the early- to mid-’60s, you could pretty much count the total number of local gay and lesbian spots on one hand. Long before there was Phoenix Pride, a Melrose district, or anyone using the phrase “gayborhood,” the Valley’s LGBTQ bar landscape was virtually nonexistent.

Stonewall certainly was one of the many catalysts for change.

In recognition of the 50th anniversary of the riots this week, Phoenix New Times spoke with those who owned and patronized the Valley’s LGBTQ establishments in the ’60s and ’70s for their memories of the era and how Stonewall affected them, the bar scene, and the community as a whole. We’ve compiled quotes from our individual conversations to create an oral history of what the Valley’s LGBTQ bar scene was like back then, what they learned, and how those lessons are still relevant today.

(Editor’s note: Some quotes have been condensed and edited for brevity and clarity.)

Phoenix of the early ’60s offered a scant number of LGBTQ-friendly bars and hangouts, including spots like the South Seas and Captain’s Table, as well as the lesbian-oriented joint Kaye’s Happy Landings.

Marshall Shore, “Arizona’s Hip Historian” and project manager for the Arizona LGBT+ History Project: Pre-Stonewall, Phoenix was very different for gays and lesbians. In the ’60s, it would not have been a place where you’d walk down the street holding hands.

There was always an edge in terms of the police getting involved. There were a handful of bars, but they were places that were more [word-of-mouth]. Where the Chase Tower is now, there used to be a bar called the South Seas. It was one of those businessmen lunch places, but then, at night, it became a gay bar.

Kim Moody, co-owner of Alwun House: South Seas was the most remarkable, elegant place. It was well-painted in blues and pinks, kind of like Copacabana-ish. They had a single stage, but they had booths all the way around. So, it was a real sophisticated place. It had very classy drag shows. It goes back to when I was coming out. I was this teenager, a freshman in college, who was brought in, underage, by a friend, and got to drink there.

Shore: When you’re talking about pre-Stonewall history, one of my favorite bar names was for a lesbian bar, Kaye’s Happy Landing Buffet. It was owned by Kaye Elledge, this short, gruff lesbian, and [her girlfriend] Violet O’Hara was very much a lipstick lesbian. It started off as an upstairs bar on Broadway and Central Avenue, and then they moved to another location. They advertised in the newspaper, but it never mentioned what kind of bar it was. There was also Captain’s Table, which was a gay bar on Seventh Street [and Missouri Avenue], but that would’ve been like the hinterlands of Phoenix at that point.

John La Noue, former manager of The Connection: I moved here in 1961, and, at the time, there were like three [LGBTQ] bars. Captain’s Table was a real casual place. It wasn’t a dress-up place … you could wear, like, jeans and stuff. It was a good place to meet people, a neighborhood bar that people knew was a gay bar. That’s the way I found out about it, matter of fact. When I moved here, my cousins, who’ve been here a long time and knew I liked to go bar-hopping, said, “Okay, there’s three bars you don’t wanna go to ever,” and, they named all three [LGBTQ] bars. And, of course, I pounded them into my brain so I wouldn’t forget.

Moody: Captain’s Table was like a much smaller crowd, and, basically, the neighborhood had a lot of gay people in it at that time.

La Noue: What was it like being a gay man in the ’60s? You didn’t really say much about it to other people, you know, unless they were close family. And, a lot of people couldn’t even talk to their family about it, you know. Fortunately, my attitude has always been my whole life, “I don’t give a shit. If you like me, that’s fine. If you don’t, fuck you. I don’t need you in my life.”

Ron Wilcox (a.k.a. Daddy Ron), manager of Nu-Towne Saloon: In 1968, I was 17-18, so I couldn’t really be a part of the gay bars, so I ended up in the little place called Act III for underage kids. It was just a gay, no-alcohol club for young men that couldn’t go to the bars. I went there with my friend, and I was terrified because I’d never been to any place like that. I was sexually sure I was gay; I just wasn’t sure about being that way in public.

Shore: There were also a lot of house parties going on. Police would raid bars and people were tired of being thrown in jail and having their information taken, so there were alternatives. Instead of having to go to a bar, you could go to a house. There was a vetting process, so if you went to a party, you didn’t just stumble upon it; you had friends that invited you, so you were kind of a known entity.

Moody: There were these mansions on Camelback that would have parties and it was a lot of fun. Boys swam in the pools, men were around, Judy Garland was playing aloud.

Shore: Parties were also being raided. I found one article from back in ’56 talking about how there was a house party where they arrested all these men identifying as [homosexual], and it gave the number of attendees and broke down which races they all were.

The Phoenix Police Department was also raiding other LGBTQ hangouts in those years. In August 1964, cops busted the 8th Day coffeehouse near First and Roosevelt streets. Twenty-three people were collared for lewd and lascivious acts or drunken and disorderly conduct.

Kim Moody: I was there. I was arrested. It was this bungalow on First Street. We were partying inside, dancing; it was a full house and very sweaty and hot. I was dancing with a teacher friend of mine. The cops came in and we just kind of froze; some tried to lurch but there were too many policemen at all the exits coming in. And I was arrested and put into a paddy wagon.

Dana Johnson, co-owner of The Alwun House: He had to call his dad from jail to come and get him out. It was so humiliating for Kim.

Shore: Whenever you had the police come in to raid, the fear was that they’d take your name, your address, and there was the threat of that then getting published in the newspaper. And when that happened, all those folks would lose their housing, their family, their jobs, without a doubt.

Moody: I worked for the federal milk market at the time, through a connection with my family. (My dad was a professor at ASU for animal husbandry.) I was fired from there. I don’t recall exactly what I was charged with, lewd behavior, probably, which they used a lot in that period with gay people. I was dancing, fully clothed, with a fellow teacher. So, what’s so lewd and lascivious about that? I danced with a black person. He didn’t get arrested; I did. It ended my career in secondary education, which I had gotten a degree for at ASU.

Shore: I found a newspaper story from ’64 about the raid and how the police chief at the time [Paul Blubaum] was being congratulated by the mayor of Phoenix [Milton H. Graham] for helping rid the city of such behavior. And you wouldn’t have even known it was gay-related, except the mayor mentioned how it was something you would find in Pershing Square in L.A., which was a notorious cruising ground.

The 8th Day coffeehouse was right near a path that later became known as the “Fruit Loop.” From what people have said, it began in the mid-’40s as a cruising area. It was kind of between Roosevelt/Portland/Third Street, and sometimes a little farther over and then the alley going up on First Avenue.

Moody: The sense of direct discrimination was so up front.

Shore: Police raids weren’t just happening in Phoenix in the 1960s; they were also happening on the East Coast or in L.A. But gays, lesbians, trans, and people of color had grown tired of it and were fed up. Stonewall was not the first or only riot; there were also riots in Florida and San Francisco that never grabbed the attention of the media like they did in New York. So, Stonewall was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

Word of the Stonewall riots in 1969 and the resulting outrage eventually reached Arizona. Some learned of the news within a few weeks or months by reading LGBTQ publications of the era. Others heard via word of mouth years later. They all had similar reaction, however.

Kim Moody: I heard pretty soon after it happened. The gay press covered it, and I read about it in ONE Magazine, which was a publication by the Mattachine Society that I subscribed to back then.

Ron Wilcox: I never learned about Stonewall until into the ’70s, because when it was going on in 1969, there really was no real gay news [outlets]. We just didn’t have all of these newspapers, magazines, the internet, and everything we have now.

Marshall Shore: When we talk about that pre-Stonewall era, it is pretty much mainstream media, because there wasn’t much until the mid-’70s that really talked about the community, for the community, from the community’s perspective. The first time Stonewall appears in an Arizona newspaper is Tucson, and it was a year after Stonewall. I’ve met folks that didn’t know Stonewall even happened until the 25th anniversary, because news was just a different thing then. It was one of those things where it wasn’t talked about. When people did hear about it, they were outraged.

Wilcox: I think once we knew about what happened, it showed that there is hope if we stay strong, there’s hope if we move forward, that those people at Stonewall did, which many people forget were drag queens. If we got on our hind legs like they did, there’s a chance that we might be accepted as normal human beings. That feeling happened all across the country, not just in Phoenix, and I definitely think it made a difference here.

Moody: We all were empowered.

Wilcox: After Stonewall, we started standing up. I mean, I’d had guys scream “faggot” at me and I’d go, “You bet your ass I’m a faggot, and if you got a problem with that, come over here, motherfucker, and we’ll talk about it.” And I discovered that standing up usually backed him right down.

Moody: Did we start fighting back? No question. Not just among my friends. The gay publications brought up the ire and focused on it and did more than one story on it, of course. But it armed us with the strength to say, “We’re not going to take it anymore.”

Phoenix’s LGBT bar scene underwent a huge expansion in the years following Stonewall. Numerous spots opened up, including Nu-Towne Saloon, Ramrod, The River Bottom, Harpo’s, Casa de Roma, Happy Gardens, and The Connection. The 307 on Roosevelt in downtown Phoenix also began its infamous run as a drag bar.

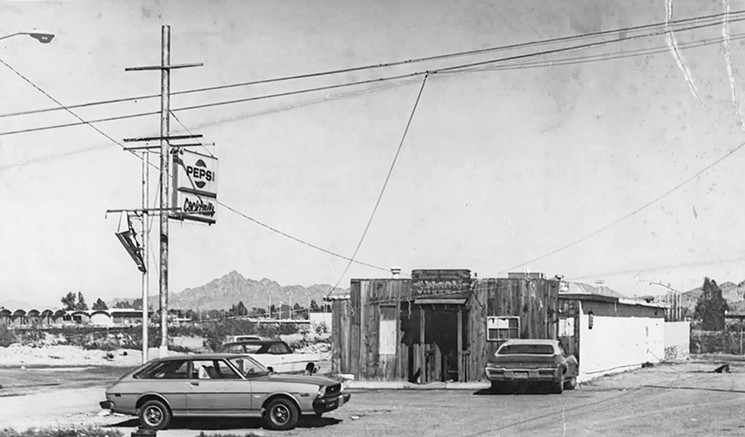

Ron Wilcox: I think people felt safer to open bars. In 1971, when Jimmy Martin and Dennis Kelly opened up Nu-Towne Saloon over on the far east side of Phoenix, they had to have some gonads on them, because there weren’t that many bars and it was out in the boondocks, really. There was nothing else out there.

Dennis Kelly, owner of Nu-Towne Saloon: It was originally a lesbian beer and wine joint ... the Papago Inn. [The owner] wanted to sell it, so I bought it. The stockyards were out there, surrounded by cattle pens. It started off, we'd have the beer busts, like we have now on Sundays, and the empty lots all around us were just full of cars.

Wilcox: The Ramrod also opened up in 1971, I think ... it was a biker/leather bar on the Black Canyon Highway right by Van Buren.

Kelly: Back in 1972, I opened Happy Gardens, which used to be a straight place and I made it a lesbian bar. Changed the entrance from the front to the rear, because most lesbians in this town were treated as second-class citizens and the ones that were successful had no place to go. We had woman doctors and lawyers. We had a band. I sold that to Rhonda [Walden].

Rhonda Walden, former owner of now-closed establishments Happy Gardens and Desert Rose: Back in the day, we separated ourselves; the guys didn’t want to be with women, and the women didn’t want to be with guys. Nowadays, it’s mixed, but it was different back then.

Char Ortega, local businesswoman and former general manager of Desert Rose: Rhonda wanted to shake things up a little bit, so women were welcome [at Happy Gardens], but so was everyone else.

Walden: We made it better.

Ortega: Rhonda was respected. She was hanging with the Tony Bartolis and Dennis Kellys of the Valley. The men's bars were very successful, and here's this strong businesswoman as well. There were some drinking moments, because when you hung with the boys, you drank with the boys. She felt like she was one of the boys.

John La Noue: There was a bar called The River Bottom, which was on 16th Street in the bottom of the Salt River. It had a pool and it was a drag bar.

Wilcox: The one thing that, and I think it took a while for it to take effect, is there was a new respect for drag queens because they were basically the ones that put the fight up at Stonewall. And they’ve always been sissified and thought of a “less than human, less than man,” and here they were the ones with the balls.

Marshall Shore: The 307 became very drag-friendly in the early ’70s. It was Roy’s Buffet at 307 Roosevelt in, I think, ’39. It then became Hubbard’s 307 and then by the ’50s, had moved to 222 [East Roosevelt], which was on the other side of the street further up. And they kept the number as the name of the bar, so it was still 307 even after it moved, and they had those [Ted] Degrazia murals that it was famous for.

Walden: Crazy, it was crazy in there [at the 307]. It was a lot of fun. Crazy fun.

Millye Bloodworth, human rights activist: My brother was Miss Ebony. My mother was gifted with a transgender child, post-op, which was me, and a gay man who loved to wear drag, which was my brother. He moved here in 1969 with his partner. He started at Casa [de Roma]. And from there, he worked at all of the clubs: the 307, The Connection. Everyone wanted to see Miss Ebony.

La Noue: I worked at a bar called The Connection for 17 years, and did all the remodeling. And the owner, Dale Williams, liked to change things around. You never knew what the hell you were gonna see when you came in, because we were always changing things. It was on Seventh Street, just north of Indian School.

Wilcox: The Connection was a huge and amazing place.

La Noue: We’d do a luau once a year, and, it was Dale’s way of thanking his clientele, ’cause it was free. There was no charge; you just had to pay for the drinks, ’cause that was the law. When it started, it was a little folding-card table with a papier-mâché volcano. Dale was a person who liked doing things bigger and better each time. So, over the years, we ended up moving into the parking lot with the luau. We made it look like a Hawaiian island.

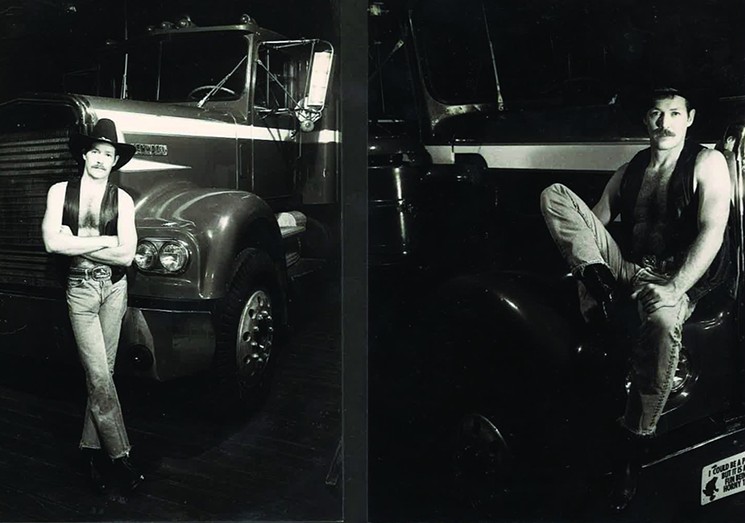

Wilcox: They put a semi truck in The Connection, which was this great visual.

La Noue: The Connection was set up as a small, long room. The space right next to it was a hardware store, and Dale eventually took that over. He put in double doors between the two and that store became The Annex, a second bar. It went through a couple changes over the years, but the final change was it became Der Druke, which is German for "the truck." It definitely became more of a leather bar. We had Harleys hanging from the ceiling, all the walls were galvanized metal roofing, and the bar was stainless steel.

After Dale went to San Francisco and a bar had the cab of an old Chevy pickup truck mounted to the wall. He thought that was really cool and wanted to do something like that, but I want it to be bigger, something that really has some pizzazz. So I said, "What if we put a full-sized [semi] in there?" We couldn't get the trailer in but we could get the truck part. So we did.

Ron Wilcox posing in front of the semi-trailer truck inside The Connection in the early 1980s.

Ron Wilcox

La Noue: I drained all the fuel out of it, took the batteries out, and you could climb in there. It had a little sleeper area on there that was well-used. And then, we'd had the truck there like six months and someone dropped a dime [on us]. And we found out later that the person that did that, knew a fireman and so he came into the bar saying, "I understand you have a truck in the bar. You can't have this truck in the bar. It's not safe."

Being the mouth that I am, I said, "Why not? I've taken the fuel and batteries out, it's all metal. There's nothing to burn." The fireman was like, "Take it out or I'll shut you down." And I was defiant. "No you won't. You try to shut me down, you, me, and every damn TV station are going to every fucking [auto] dealer in this city and say, get those fucking cars out of there, because they have a battery and gas in them."

Wilcox: John had a real temper on him.

La Noue: The fireman said, "Well, I'm calling my chief," but we would up never having to move the truck. They weren't going to do to me what they couldn't do to others. That's illegal.

Bloodworth: HisCo Disco also opened in the ’70s. It was a big huge building that played dance music. It was a melting pot of everybody: heterosexual girls that had jungle fever and girls that wanted to date gay boys. I worked at Saks Fifth Avenue, so it gave me the opportunity to get my clients, because everybody wanted a gay friend at that time so they could show you off and have you at the parties.

Tony Bartoli, former owner of Casa de Roma, JR’s Hideaway, and Harpo’s: There were times when we didn’t have signs out front. The signs would be in the back, if you had a sign. There were no windows in the old bars. Bricks would come through. It wasn’t a lot, but it happened.

Pat Olivo, owner of Pat O’s Bunkhouse Saloon: After Stonewall kind of changed things, we were out front with signage and everything.

Wilcox: A lot of gay bars only had back doors. And most of the entries were in the back, because of privacy. You parked in the back, you looked around when you got out of your vehicle. You went in and you stayed in. You didn’t loiter outside.

Bartoli: I was always amazed at all these guys who were married with kids and they would always come through in their shirts and ties. There were judges that didn’t want anyone to know they were there. We had sneak ’em back home, call ’em a cab driver we knew that could keep secrets.

Wilcox: It was amazing to walk into some place you knew was going to be full of like-minded people. The camaraderie, the companionship was unbelievable. It was the only place you could go where you felt like you were a normal human being, because for years, in the ’50s when I was growing up, if you were considered gay you were either a pedophile, a pervert, or a freak.

Even in the ’60s and ’70s, we were still fighting that stigma. But the feeling of walking into a place where you didn’t know a single person there and they instantly became your friends, was great. You couldn’t go to a straight club and feel that way, because sometimes you didn’t know if you were getting out alive.

Bloodworth: Not every [African-American] wanted to go out to the hoity-toity bars. They didn’t want to be bothered with the snootiness. They’d go to 307, they’d go to Tempe. There were all these “fruit stands,” which is what my brother called the bars in those days. It was fun for me here, because I could go to the hoity-toity [bars] and be a raisin in a pot of rice and be wanted ... and the white man that I dated would love to flaunt me in that way.

La Noue: I think all the gay bars blooming in the ’70s was partly an effect of what everyone was feeling. Because people had the attitude of, “No. I’m gonna open a damn gay bar and fuck you.” Because when you have that attitude, you branch out and you do things you wouldn’t normally do, like you wouldn’t even think to open a gay bar before because of all the harassment.

The harassment of LGBTQ bars by the police, or even gay-bashers, didn’t disappear in the 1970s.

Pat Olivo: That was a major thing that happened back then. I’ve lived here since 1976, but also came here a lot when I was younger. The police used to come in and harass us in the bars when I was here [in 1972] and I was young. Four or five would come in and your hands had to be on the bar, they couldn’t be in your lap or anybody else’s lap. And they were just there to harass you, they’d walk through. As if anybody was doing anything illegal. We were just sitting there drinking.

John La Noue: Cops were definitely coming through The Connection in the ’70s. And our doorman could push a button to notify us inside. And then we’d go flip the lights on in the restrooms. You never said a word, because you didn’t know if there were [undercover cops] in there. Everybody knew what the hell that meant, you know, and they’d clear out.

Tony Bartoli: I’ll tell you a good story. I owned Casa de Roma, and we were across from a ball field. And the kids knew there was a gay bar there. They came in my bar with their baseball bats and so forth. They were 17 and 18 years old, and they were going to get a couple of faggots, and they were messing with the wrong faggots. I swear to Christ, we chased them out of that bar so fast … they never looked back. That was such an unusual incident.

Olivo: There was a bar [Miss Matty’s Attic] up on 32nd and Shea, and they would come with baseball bats and break the windshields and the taillights, and the headlights.

Ron Wilcox: Sometimes, people really feared for their lives. I watched people being unlocked out of their trunks at The Connection where they’d been mugged and locked in their trunk.

La Noue: I remember one time specifically that there was like two or three [homophobes] in a car and hollered “faggot,” and said, “Are you looking for trouble?” And, I just hollered back at ’em, “I don’t ever look for trouble. What’s your problem?” Usually, I found if you confront them head on, they don’t wanna get hit. They’d rather leave.

Not every confrontation at an Arizona gay bar had such a happy ending. In 1976, a 21-year-old Nebraska man named Richard Heakin was beaten to death by three teenagers outside of the Stonewall Tavern in Tucson. All three assailants were given probation, which caused an uproar in the city’s LGBTQ community.

Shore: He was a young man out for a night on the town and it was shocking and out of place to be brutally beaten like that, even back then. I would equate it now with what happened to Matthew Shepard. So that's why there was such a strong community reaction to that. The kids that did also got a super-light sentence from the judge in the case. A year later, it led to Tucson passing one of the first anti-discrimination laws in the country and was the catalyst for Arizona’s first pride organization in Tucson. So it also affected not just the community but the legal aspect as well.

Phoenix Pride debuted in June 1981, when hundreds of members of the Valley’s LGBTQ community marched from the now-demolished Patriots Square Park to the Arizona State Capitol. Many local bar owners and their employees participated.

Ron Wilcox: I marched that first year. We were surrounded by cops, and we were terrified. You were going to step out on the street; unlike going to the back door of a bar where you could park behind the building, you were going to put your face out there where there were news cameras. If you had a job, you could probably kiss that goodbye, even then. And you didn’t know who was going to be waiting for you at home or anything else after that. You just weren’t sure. Because at that point, not everyone out there was necessarily gay-friendly.

John La Noue: Everybody was watching each other’s backs, just to be safe. You had to be aware of your surroundings, because you didn’t know. I mean, it had never been done before, not here at least. And the cool thing is, and it’s true with anything, you can start out small, but it can grow. And, every time we’ve had pride marches, parades, or festivals, more people have gotten the courage to do it. And they get this attitude, what I call the fighting attitude. It’s like, “No, I’m gonna do this. If you don’t like it, deal with it.”

Members of Phoenix’s LGBTQ community think that the lessons they learned after Stonewall are still as relevant as ever.

Pat Olivo: Some of the younger kids today don’t know the old history. So, they’re taking it, and what we have now, for granted. Not all of them, of course … I have some very close friends who are young and are up on it. Some of them, though, just aren’t aware of the history we all experienced, but they should be.

Kim Moody: There was a definite divide in society at that time; there still is to this day. There will always be individuals who think we’re abominations, but we’re not and never have been.

Ron Wilcox: It’s hard to believe in our community in this day and age, with all these devices we have at our disposal, there are still people out there that are still learning that we had to stand up for ourselves. I think it’s just like any other group that’s had to fight for their rights, people that are considered second-class citizens or the others of society. There are still kids today who will confront us, call us names, or get in our faces. And I’m still like, “You want to call me queer? Call me queer. I’m a queer and I’m proud of it.” And without Stonewall, I would not be doing this.

Phoenix New Times would like to thank Marshall Shore for his assistance with research for this story.