In the late 1980s, archaeologists made an usual discovery at Pueblo Grande: a group of clay animal figurines. Seven dogs, about four to five inches in height, rested 12 centimeters below the soil in the floor of a Hohokam pit house. Why they were made and what they were used for remains a mystery.

Holly Young, collections curator for the museum, speculates that the dogs, two of which appear to be pregnant, may have been part of fertility rituals. Each figure has a hole in its posterior that Young suggests could indicate a dog in heat rather than being a generic representation of — well, you can use your imagination. Archaeologists do that all the time, since very little is known about the religious beliefs and practices of the Hohokam Indians, who originally settled the Valley. Though animal figures and effigies can be found in their art, any meaning suggested remains speculative. For example, representations of frogs are found fairly frequently, leading researchers to believe that they were symbols of water.

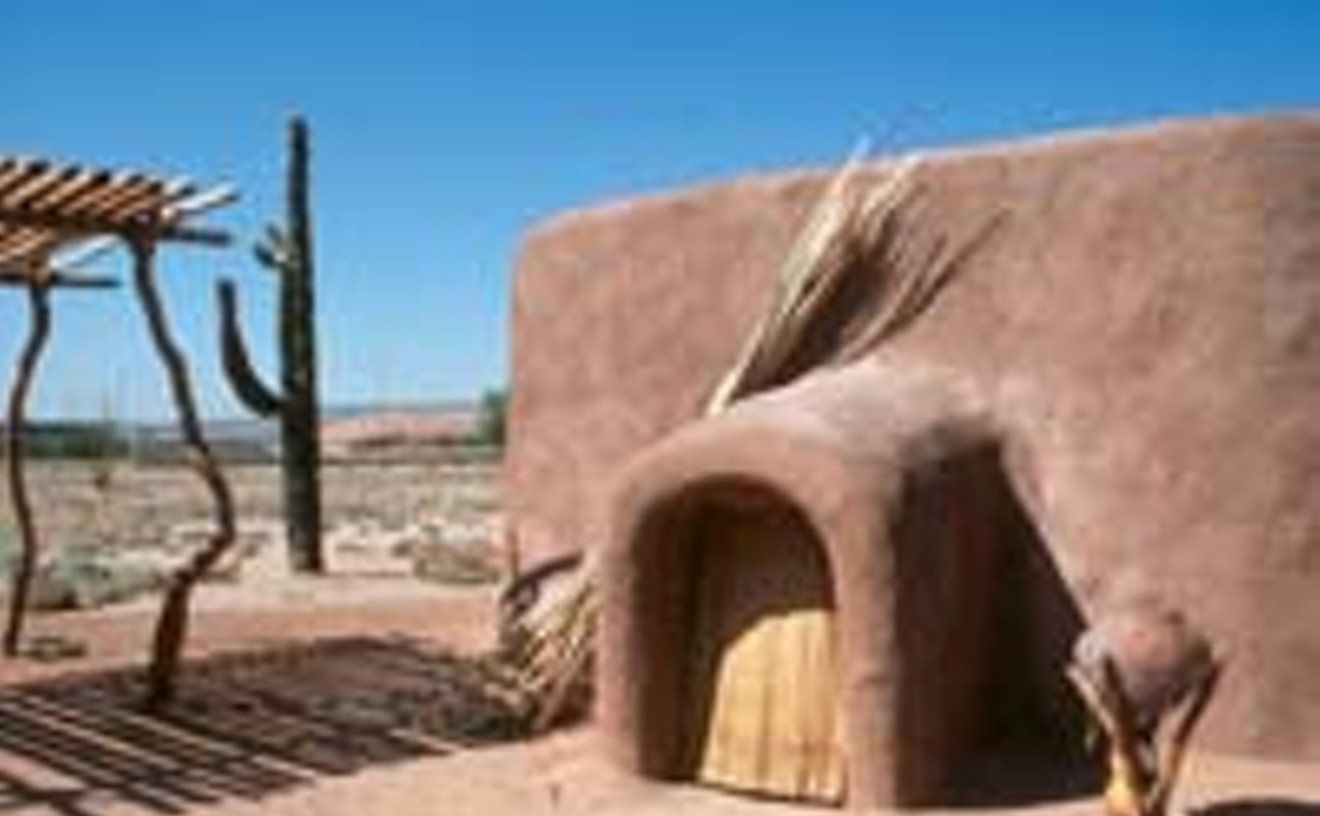

The Hohokam flourished in this region from about 500 to 1450 A.D., though the starting dates continue to be pushed back as more and more evidence is unearthed and as archaeological methods become more sophisticated. They were an agricultural people who developed a complex irrigation system to grow crops like corn, beans, and squash.

Evidence from the soil has shown that the area was densely settled. "The landscape was dotted with villages," said Young. "There were quite a few people actually living here, farming, working." After the Hohokam society collapsed — perhaps due to natural disasters or disease — the Valley did not regain the same population density again until after World War II.

"It's a very subtle archaeology," Young says of her work. "It's not like going to places like Egypt — it's hot and dry and dusty there — but you've got big buildings that you're digging around and that kind of thing, whereas here we're basically looking at stains in the soil.

"The depth of digs in the Valley ranges from a few inches to several hundred feet, depending on the position of the bedrock. Closer to the Salt River, where hundreds of years' worth of silt deposits have accumulated, excavations tend to go deeper. But just as mid-century homebuilders discovered that the layer of caliche made house construction complicated, archaeologists found it to be an obstacle for their work as well.

The Hohokam themselves encountered caliche in their own time. It was used to carve artifacts, added in pottery clay, as well as mixed in with plaster to create smooth surfaces.

So what of our society? How will our remains fare over the ages? "It depends on how we go away," Young says, laughing. Within a few hundred years, everything that makes up Phoenix probably will be underground.

"Obviously, the glass is not going to last that long because it's brittle and it will break. Steel is going to last a little bit longer, until it starts rusting. So it all depends on how a society gets destroyed, what happens to its structures to begin with. If there's a neutron bomb and buildings are still left standing, it may take a lot longer to degrade. If it's something like a massive earthquake or a conventional nuclear weapon, it might go away fairly quickly," she says.

But our day-to-day materials do not stand a chance of outlasting Hohokam treasures.

"Plastics, of course, fall apart pretty quickly, especially when exposed to sunlight," Young says. "Most of the metals that we use, like iron alloys for cans and stuff like that, they fall apart incredibly fast in the desert . . . We're talking a matter of centuries for all of the metal things to go away."

Indeed, she says, a copper bell found at another Hohokam site nearby — likely dating to the 15th century — "probably survived better than just about any of our metal artifacts will."

To see a slideshow of artifacts from Pueblo Grande, visit www.phoenixnewtimes.com/bestof2011.