I grew up in Winslow, a town that took one lyrical mention in the song “Take It Easy” written by Jackson Browne and Glenn Frey and turned it into a claim to fame.

Well I’m a-standin’ on a corner in Winslow, Arizona / Such a fine sight to see ...

Legend has it Jackson Browne wrote the song after car trouble stranded him in Winslow. His neighbor in Los Angeles, Frey, provided the unforgettable lyrics to the then-unfinished second verse, based on Browne’s sighting of a woman outside a Der Wienerschnitzel in Flagstaff.

It’s a girl, my lord, in a flatbed Ford, slowin’ down to take a look at me.

If you were a kid in rural Arizona in the 1970s, like I was, the Eagles’ songs were everywhere: “Hotel California,” “Desperado,” “Take it to the Limit.” With their mix of rock and country influences, with their lyrics about the pursuit of the American Dream, chasing the high life, and nights spent in the desert, the Eagles were a band lots of people in Winslow felt like they could relate to. The 1970s took a toll on Winslow when construction of Interstate Highway I-40 bypassed the town. Seemingly overnight, the historic downtown, located on old Route 66, started to look forlorn and shuttered.

Not to mention, the 1970s lasted a very long time in Winslow — well into the 1980s, even. Before the democratizing effects of the internet sped up the rate at which we received news of the latest trends, change there took time. The town limped along.

Then, in 1999, as a way to attract tourists, the Standin’ on the Corner Park (there is no g) was opened to the public. The park included a two-story mural of a girl in a flatbed Ford and a life-sized bronze statue of a 1970s-era troubadour, who locals call “Easy,” wearing a vest and holding a guitar while standing casually cool on the corner.

The park was an opportunity. A photo opportunity, certainly, but it also represented a plan to lure tourists off the freeway that sped past the northern edge of the city with its off-ramps and on-ramps allowing access to Wal-Mart and fast food, skirting past everything else old downtown Winslow might have to offer.

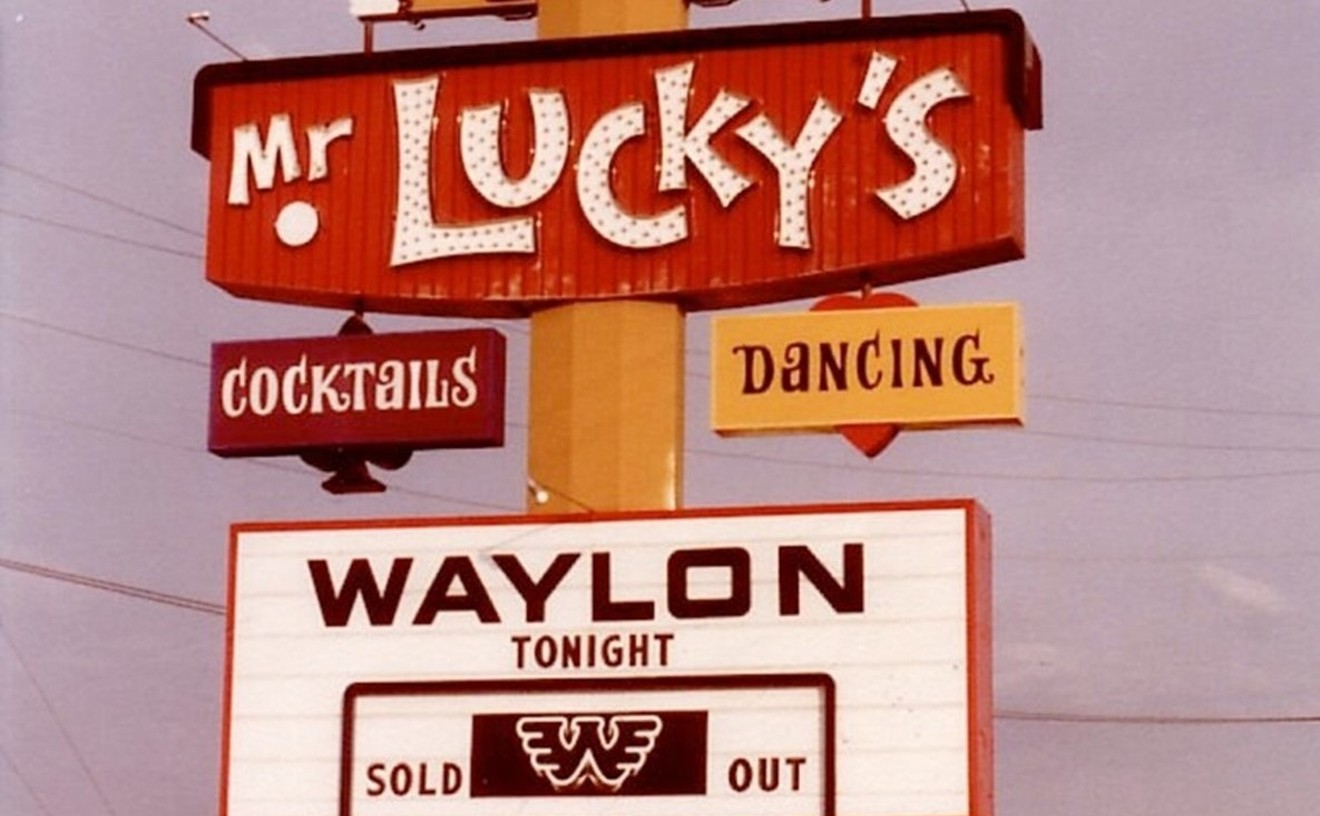

That same year, a music festival was started. Initially a dedication celebration for the park’s opening, the Standin’ On The Corner Festival grew into an annual two-day live music celebration, held each September and concluding on Saturday night with the performance of an Eagles cover band.

All this to say, that morning last Jan. 19, my dad needn’t have worried that the town would drop the ball. By the afternoon, a makeshift memorial to Glenn Frey was well underway.

My dad texted pictures (I had moved away from Winslow to Phoenix after having spent several years in Brooklyn, N.Y.) and sent updates charting the progress of candles and wreaths being placed in the park next to the statue. I used to think of my long-haired dad, a railroad engineer who drove freight trains from Winslow to just outside of Albuquerque, as so quintessentially a “Winslow” guy (he was a founding member of the Standin’ on the Corner Foundation) that once, in my 20s, I took a series of photos of him standing on each corner along my hometown’s streets.

That night, dozens of people gathered to sing along to Eagles tunes, sway to the music and pay their respects, some dropping off flowers and notes. The homegrown event got national press.

Down in Phoenix, 100.7 KSLX’s morning radio team, Mark and NeanderPaul, also wanted to do something to honor Frey, something aside from “hey, we’re going to play an album side,” says radio host Mark Devine. The pair approached the Standin’ on the Corner Foundation. One thing led to another and, when KSLX kicked in a sizable $15,000 donation for the project, plans to acquire a life-size bronze statue resembling Frey were put in motion. The city of Winslow and the Standin’ on the Corner Foundation also pitched in with contributions for the project’s estimated $22,000 price tag. Friday, September 23 at noon, a statue unveiling and dedication will take place to kick off the 18th Standin’ on the Corner Festival, a live music event that will run September 23 and 24 in Winslow. Mark and NeanderPaul will be there broadcasting their morning show and the dedication ceremony.

Winslow has made a cottage industry out of its mention in the song “Take It Easy,” and Frey’s death certainly created an uptick in attention for the little town in northern Arizona. But call me a cynic: I wonder how long could this song be relevant enough to help my hometown stay on the map.

It wasn’t even a whole song about Winslow. It was just two lines.

The Eagles put Winslow, Arizona, on the map with their song “Take It Easy.” Now, more than 100,000 visitors a year stand on the corner at the Standin’ On The Corner Park at Second Street and Kinsley Avenue.

Andrew Pielage

“Oh gawd!” says my friend Amy, “the Eagles!” She’d just been on a road trip, which included a stop in my hometown where she’d discovered what I already knew. There is a store on the main drag with outdoor speakers that play the Eagles over and over on a continuous loop. All day. Actually, there are two stores, on either side of the intersection, that sell souvenirs and play the Eagles. “You must never want to hear them again,” she groans.

She’s partially right. There was something schlocky about it, sure, maybe because it’s easy to be jaded about the place where you grew up. But I wasn’t exactly sick of it — more curious about my town’s commitment to what could seem like a damn foolish idea. Both the song and my hometown were like historical markers of the 1970s, and I wondered: Could a song make a town?

All of this is on my mind as I pull into Winslow in late August, weeks before the Frey statue is to be dedicated. I park my car and step out. “Life in the Fast Lane” is being piped across the intersection: “Surely make you lose your mind / Life in the fast lane.” A half-dozen biker types, all old enough to be grandparents, are gathered around “the corner,” wearing black leather vests with patches sewn all over them, foreheads covered by tightly tied bandanas. I get closer and see they are a group of combat vets riding Harley-Davidson trikes.

The corner in question is located at Kinsley Avenue and Second Street in downtown Winslow. The Standin’ on the Corner Park sits on the northwest side of the intersection; across the street is the souvenir shop Dominique’s, the one playing the Eagles on a continuous loop. As I cross the street to the southwest corner toward the Arizona 66 Trading Company, I realize they, too, are playing Eagles tunes. Dominique’s has a mural of the "Cars" character Lightning McQueen painted on its windows, and the shop on the other side of the street, not to be outdone, has a giant red guitar on the sidewalk outside the store. The final corner of the intersection houses the Sipp Shoppe, serving coffee, ice cream, milkshakes and sandwiches out of the historic 1904 Bank Building.

As I’m standing there checking out the bikers busy taking pictures, two younger women get out of a car with California plates and make their way to the corner. Both are wearing straw cowboy hats, the kind tourists wear, not actual cowgirls. They pose in front of the statue, hamming it up. Not a minute later, another couple is out of their car, and they line up to join the queue. It’s a random Thursday in late August, and a continuously steady stream of tourists get off the freeway and find their way to downtown Winslow.

Back in Phoenix, I call up Jason Patrick Woodbury, music journalist and former music editor of Phoenix New Times, to talk about what made the Eagles so hugely popular in the 1970s.

“The Eagles,” says Woodbury, “for a band that’s so musically benign, they engender super-strong opinions. People deeply love the Eagles, and some people despise the Eagles.” It’s like the band became a stand-in for yuppie culture, for ’70s soft rock, for a laid-back, take-it-easy approach. So maybe people are talking about hating the “idea” of the Eagles more than the Eagles themselves.

By the group’s heyday, “the idealism of the ’60s psychedelic hippie had soured,” says Woodbury, “but we were still left with a landscape acclimated to guys with long hair and dirty jeans.” There was no revolutionary message in the music, no hungrily upsetting the status quo. The Eagles’ gorgeous harmonies are aspirational, meaning “you want to be as chill as an Eagles song,” he adds. But it’s this same quality that makes some people view them as phony.

There’s no better pop cultural reference to this than the scene in "The Big Lebowski" where Jeff Bridges’ character, the Dude, is riding in a cab and the Eagles are singing, “I want to sleep with you in the desert tonight.”

The Dude pleads with the cab driver, saying, “Jesus. Man, could you change the channel?”

“Fuck you!” says the cab driver, “If you don’t like my music, get your own fuckin’ cab!”

“Man, come on. I had a rough night and I hate the fuckin’ Eagles, man!”

I ask Woodbury, “Do people born after 1990 know who the Eagles are?”

“Yes,” he says. “Everybody has heard, and is still hearing, the Eagles constantly. That music is still being played on the radio.” Meaning some of those songs are still close, the repetition of them looping around in our consciousness. Lisa and Melissa, who operate the Eagles fan website L&M’s Eagles Fastlane, say the reason the Eagles’ music is so enduring is probably put best by Glenn Frey in the "History of the Eagles" documentary.

“He said that during the ’70s, people did things to the music of the Eagles. They fell in love, they fell out of love, they hung out with friends, they went on road trips, and started families. That music was there while they did that, so people have a very tangible connection to those tunes.”

Do you think people will be singing these songs like, say, we sing Hank Williams?

“Gut response is ... maybe,” says Woodbury.

The Eagles, he points out, have baffling sales figures. They are one of the greatest-selling bands of all time. Almost every record collector has one of these albums, Woodbury says. “You’re not even sure how they show up, it’s like a Bible or a relic that, who knows? They’re just there.”

So I ask Greg Hackler, chiropractor and founding board member of the Standin’ on the Corner Foundation in Winslow, who’s been there from the park’s start, “Do you think you’ll ever get tired of listening to the Eagles?”

“Me? No. You know it’s just great harmony — good music. That’s why this group continues to resonate. I can’t say I’ll always listen to, um, "Bat Out of Hell," by Meat Loaf, (released in 1977; one year after the Eagles’ "Hotel California") but I’ll listen to the Eagles for the rest of my life.”

If a town was going to bank on something, why not this?

To get a sense of numbers — how many people were stopping at the park in a day — I spoke with Sabrina Kislingbury Butler, another board member, who happens to work at the Arizona 66 Trading Company gift shop, which gives her a fantastic vantage point to see, and interact with, people stopping at the park.

“It’s been so busy this summer,” says Butler. “Summer is usually a busy season, but this has definitely been busier than I’ve seen it.”

“Do you think that has something to do with Glenn Frey’s death?”

“Probably. Last year, traffic was about 50/50 between Route 66 fanatics and Eagles fanatics. This year, it seems like a lot more Eagles fans.”

“How many people stop in a day?”

“I’d say hundreds, maybe thousands, in a day.”

“That’s incredible,” I say, almost disbelieving. “So, thousands in a week?”

“Oh, easy,” she says.

This is echoed by Steve Pauken, city manager for the city of Winslow, who tells me Glenn Frey has doubled tourism in the town this year.

“Really?” I ask. “Is it that noticeable?”

“No doubt about it,” he says. “Everyone in town has noticed it. No matter what they do.”

That means the park is receiving well over 100,000 visitors a year. And that is not an insignificant number.

The Standin’ on the Corner Festival, always the last full weekend in September, is easy to book ahead. Attendance at the festival, depending on the weather, is estimated to be anywhere from 4,000-8,000 in a town with 800 hotel rooms.

Later, walking through the La Posada Hotel, I ask the front desk clerk, “Do you get a lot of business the weekend of the Standin’ on the Corner Music Festival?”

“Oh yeah!” she says. “We’re completely booked for that weekend.”

“How far in advance do people book rooms?”

“We have people who come to the event, and book their room for the next year before they check out.”

Still, not long after arriving, I hear that at a mid-August meeting, held in the festival pavilions, board members were still voting on what the statue would look like, and where it should be placed in the park. Would it be done in time for the dedication? I felt a little relieved, knowing that the town was cutting it close. Too much unchecked boosterism was making me uncomfortable.

The Winslow Visitor’s Center is located inside the historic Lorenzo Hubbell Trading Post and Warehouse building, built in 1917. When I-40 bypassed the town in the 1970s, Winslow’s downtown fell on hard times.

Andrew Pielage

A lot of people who grew up in Winslow, like I did, referred to it as The Slow, or The Slows, like it was a condition. I can visualize my town with my eyes closed. Railroad tracks running from east to west. On the outskirts, red dirt with a slight vegetative cover in muted greens. Plants barely tethered to the earth, ready to pick up and tumble along in any gust of spring wind.

Follow a line of semi trucks rolling by town on Interstate 40, and you’ll see a smattering of trailers in a trailer park, a business called Curell’s Bargain Barn, nameless old motels, a garage missing any sign of being open for business except for motor oil stains, a furniture store located in a former bowling alley, another garage with washers and dryers and appliances lying about scattershot, little houses with yellowing yards, barking dogs, an old downtown spotted with blank plate glass windows.

“Who the hell lives here?” you could almost hear people thinking as they gassed up their cars.

The answer was simple: We did.

I was born in 1971, the same year Frey, Don Henley, Bernie Leadon and Randy Meisner started a band in Los Angeles.

Sometimes, I thought my early life had all the makings of a country-and-western song.

My mom and dad, who’d both grown up in Winslow, were high school sweethearts.

My dad went to work as a railroad engineer. My mom was an elementary school teacher. Our first home in town was an aluminum-sided, two-bedroom trailer on a small plot of dirt. The trailer park faced the high desert; at the end of the unpaved road lay the Winslow Cemetery. It had ONE WAY signs posted at the front gate.

By third grade, my parents bought an old two-story house. It sat on a corner. They hadn’t just bought the place to restore its original beauty, they’d bought it to bring change. In short order, they went about fixing it up, renovating and reinventing.

I can tell that Winslow has done a lot of beautification in the last few years to its streets and sidewalks. The city manager, Steve Pauken, tells me the city is in the fifth part of a six-phase Route 66 renaissance, part of a state- and federally funded $10 million project.

“Starting at the west end of town and working eastward we’ve replaced curbs, gutters, streetlights, put new paving where necessary. It’s major face-lifting,” says Pauken. The city is also changing all streetlights to night-sky-friendly LED fixtures. This will not only help preserve views of the night sky, but cut down on electricity use by 65 to 70 percent.

These projects were begun before his tenure, but, says Pauken, “there was an awful lot of blight when I started working here. When I came in 2014, I made it a priority to clean up the blight.”

Winslow is a railroad town founded in 1882, its location chosen as a major division point for the railroad because it had a dependable water supply from the Little Colorado River, which was needed to power the steam engines of the late 19th century.

The La Posada, the last of the Fred Harvey hotels built by the Santa Fe Railway, opened here in 1930. Designed by architect Mary Jane Colter, it is considered her masterwork. Passenger trains from Los Angeles to Chicago delivered well-heeled guests to the resort hotel, but by 1957, rail travel declined and the La Posada closed. A few years later, it was turned into offices for the Santa Fe Railway, drop ceilings and overhead fluorescent lights dimming its grandeur.

After the bypass went through, leaving Winslow’s downtown cut off from travelers, another blow came in 1993 when the railway announced it would be moving out of the La Posada for good.

The buildings stood empty, and the railway stopped watering the grounds. An ad-hoc group of volunteers came together to care for the vulnerable gardens. The Gardening Angels, as they were called, were instrumental in keeping the grounds alive. Members of the group also successfully got the La Posada a National Register of Historic Places designation, further protecting it, and the La Posada Foundation was formed.

In 1994, the La Posada Foundation began working with the city of Winslow on the redevelopment of the downtown area. One of the Foundation’s projects was the development of a mini-park, measuring 26 feet by 134 feet. The theme: Standin' on the Corner In Winslow, Arizona, taken from the Eagles’ song “Take It Easy.” The lot for the mini-park was the location of a former business known as the Catch Pen, owned by a local Winslow family. The building burned in 1992 and had been razed; only the lot remained. The Kaufman family gifted the lot to the La Posada Foundation for the creation of the park.

When the National Trust for Historic Preservation placed the La Posada on its endangered list, it drew the attention of entrepreneur Allan Affeldt. He visited the hotel in 1994, and for the next three years, negotiated the purchase of the hotel from the BNSF Railway (with the help of the local preservationists). Though not a hotelier, in 1997 he and his wife, artist Tina Mion, moved in and began the extensive restoration process. With the La Posada’s future secure, the nonprofit La Posada Foundation renamed itself the Standin’ on the Corner Foundation and opened its park on Sept. 11, 1999. The park’s history was a story of resilience.

The town wouldn’t let itself die.

Driving through town this August, I notice an old motel with a newer hand-painted sign that says “Sleepin’ on the Corner,” and a sewing and alterations shop called, “Stitchin’ On the Korner.” I smile: It’s like the joke of adding “in bed” to the end of any sentence. Was my town’s version adding “on the corner?” And had everyone agreed at some point by secret ballot to drop the “g” from their verbs?

“What’s it been like to see the park evolve over the years?” I ask foundation board member Greg Hackler.

“Unbelievable,” he says. “We didn’t know what kind of impact the park would have. We thought it would ... maybe draw people from around the state. But early on, people believed in what we were doing.”

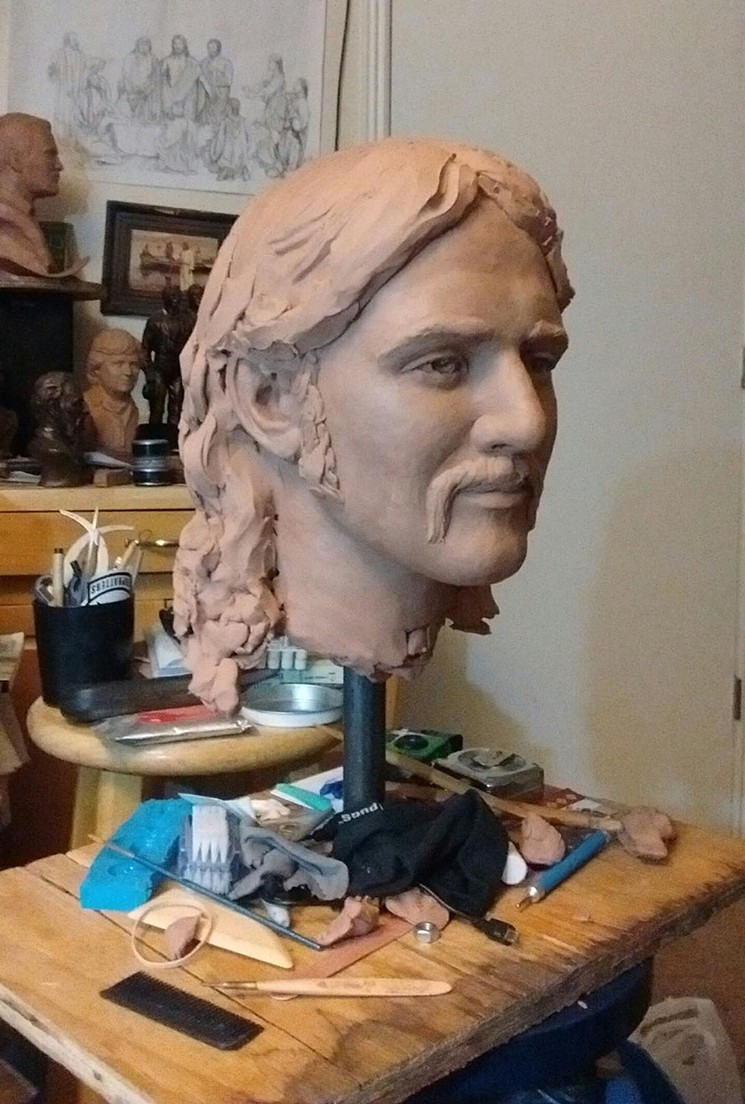

The new bronze statue of Glenn Frey’s likeness will portray him leaning with his hand on a light pole, casually surveying the action on the corner. At least that’s what I’ve been told.

I ask Hackler good-naturedly, “Will the statue be ready in time?”

“I was assured last night it’s in the making right now,” he says. “At our original statue unveiling (in 1999), ‘Easy’ came in at the very last minute in the back of the artist’s truck.” Volunteers hurriedly gathered at the park to help set the statue, finishing with little time to spare.

“It almost feels the same now,” says Hackler.

I started out thinking getting another statue was a pretty corny idea. But now, I’d begun to feel impressed. The Standin’ on the Corner park was a grassroots effort that showed signs of success, attracting a mix of Route 66 buffs, Eagles fans, train diehards, Mary Jane Colter enthusiasts and those looking for Radiator Springs.

“Take It Easy” wasn’t just about having a loose, relaxed approach to life, but, to those of us who grew up in Winslow, it spoke to the idea that everyone went through hard times at some point — something many Winslow residents could identify with. Twenty-six percent of residents are living with incomes below the poverty level, which is much higher than the national average. And the city has experienced stagnant population growth for a number of years. I haven’t lived here since high school, but I’m frequently drawn back by the people and the natural beauty of the surrounding area.

A comprehensive tourism survey conducted by the Winslow Chamber of Commerce back in 2012 captures signs both positive and negative. When asked to describe their experience in the Winslow area, by far, the most frequent comment tourists made noted the friendliness of the people. On the other side of the coin were comments such as: needs more places to eat, wish the area was doing better economically and needs rejuvenation. That seems like a pretty fair assessment.

The pace of revitalization is way too slow. That’s the simple answer. Pauken says, “I watch TripAdvisor, and I’m just as discouraged as anyone when I read, ‘I went to the park and then left because the rest of the town is a dump.’’’

“People would drive through looking for something. Now, people get out and look around,” says my dad, Bert. “But most people pose for some pictures and head out of town.” The trick has always been keeping them here.

Winslow has made progress. The number of people stopping has increased tremendously. The La Posada is listed on Conde Nast Traveler’s Gold List. The Old Trails Museum, just down the street from the park, is a fantastic (and free) local history museum worth the stop; the Winslow Visitor’s Center is housed in the restored Lorenzo Hubbell Trading Post and Warehouse building constructed in 1917. The ancestral Hopi villages at Homolovi State Park are 5 miles away. The Petrified Forest National Park is located 50 minutes east, while Walnut Canyon National Monument is 50 miles northwest.

And hey, now the town will have a new statue in the likeness of Glenn Frey.

It is hard to know how much annual revenue the park brings to Winslow without knowing the dollar amounts that all the restaurants, hotels, gift shops and gas stations attribute to visitors of the park versus visitors to La Posada versus visitors to other area attractions. Says Bob Hall, CEO of the Winslow Chamber of Commerce, “You are not the first person to ask that question. I wish I had a clearer answer but suffice to say, tens of thousands.”

I ask Sabrina Kislingbury Butler, “What happens when people start forgetting who the Eagles are?”

“It may come to an end at some point,” she says, “but parents share their music with their kids, and the kids end up loving the music, so I’m hoping that it keeps going on, and hopefully we can always find ways to keep it fresh.”

You know, the Beatles refer to Tucson in “Get Back,” but there’s no statue of Jo-Jo. I’m starting to think maybe there should be.

Jo-Jo left his home in Tucson, Arizona / For some California grass.

I reach DJ Bawden, a sculptor and owner of Total Statue in Provo, Utah. He’s got the commission to complete the Glenn Frey memorial. He confirms work on the statue is underway. Asked to describe it, he says it’s a hippie-looking guy with a Fu Manchu mustache that resembles a 1971- or 1972-era Glenn Frey. He’s got his left hand in the hip pocket of his jeans.

“How’s it coming along?” I ask.

“Coming along fine. Head’s all finished. Should be headed to the foundry next week,” says Bawden. The statue is another tribute to an analog world, to an era when a song was written and a freeway bypass was about to change the way a small town viewed itself.

The Standin’ on the Corner Festival culminates on Saturday night with the performance of an Eagles cover band, which a few years ago, the last time I was in attendance, was the all-girl Eagles tribute band the Sheagles.

That night, I sat on a patch of grass with my brother and sister-in-law, my daughter and my spouse, watching the crowd dance to a Mexican banda band. Kids ran around with marshmallow shooters some enterprising vendor has made out of PVC pipe, scattering marshmallows across the dusty pavilion. One particularly exuberant man, who we nickname “the Scarecrow” because he is so tall and skinny, keeps raising his arms, outstretched and flapping, to draw more people out to the dance floor. What unites everyone is a mix of music, Navajo tacos, a light coating of dust kicked up by dancers’ feet and beer.

When the Sheagles come on, my fellow townspeople gather around the front of the stage and stare at the eight female musicians from Nashville, seemingly tentative. But they warm up after just a couple of songs, after one of the Sheagles challenges into her mic, “Let’s hear it, Winslow!”

Their set is made up entirely of Eagles songs, building to the one song that is the cornerstone of the whole event.

“Take It Easy” is not, arguably, one of the Eagles, greatest songs, and yet, you could walk into a bar literally anywhere in the country and say you’re from Winslow, Arizona, and someone’s going to remember that lyric.

That song gave us something to believe in — this town that metaphorically wants someone to slow down and take a second look. That’s what a song can mean.

This article was originally published in 2016.