If there were a Mount Rushmore for film directors who know how to put together a perfect soundtrack, whose faces would be chiseled in the rock? Martin Scorsese, Wes Anderson, and Quentin Tarantino spring to mind.

Scorsese has used old school rock ’n’ roll with such deft skill that any modern filmmaker who uses The Rolling Stones in a film should cut Marty a check. It’s impossible to imagine any of Anderson’s immaculately constructed twee masterpieces without the blend of ’60s pop, French ye-ye music, and Brazilian Bowie covers he scores them with. And Tarantino is just as quick to show off his record collection as his movie knowledge — any Q.T. film is bound to come with a few killer soul jams, surf rock, or Nancy Sinatra torch songs to spice things up.

You can’t have a Mount Rushmore with just three faces, though. And if anyone’s earned a spot up there with the big three, it’s Edgar Wright.

The English filmmaker got his big break on the cult TV show Spaced (1999-2001). It’s where he met Simon Pegg, his leading man and co-writer for many of his films. It’s also where Wright first displayed his talent for marrying comedic material with the kind of dramatic filmmaking techniques you’d see in horror or action films.

You don’t have to look further than Wright’s 2017 film, Baby Driver, to see how good he is at using music to further his vision. The film plays like a bangin’ mixtape with a few jaw-dropping car chases thrown in for extra sizzle. From The Commodores and T-Rex to The Damned and Queen, it’s a soundtrack that crosses oceans and eras. It’s also a film that makes music a key part of its plot. Baby is a getaway driver with tinnitus, and he plays music constantly through his headphones to drown out the incessant buzzing in his ears.

Wright’s music choices in Baby Driver feel deliberate and purposeful. Consider the “botched” getaway scene when Flea and Jamie Foxx’s characters hit a bank. Wright scores the scene to The Damned’s nervy, adrenalized “Neat Neat Neat,” a punk song that speeds past with so much energy it sounds like the instruments could fly out of their hands at any moment. Not only is it a catchy song, it perfectly captures the chaotic mood of the scene.

When used properly, soundtrack choices can have the same power that song and dance sequences have in musicals. It’s often said that the songs in musicals happen during moments where the characters are feeling emotions too powerful to be expressed in words. The songs aren’t just songs: they are moments of revelation, moments where characters connect with each other in a deeper way.

A great example of this is the way Wright uses Queen’s “Brighton Rock.” Baby shares the song with one of his criminal associates: splitting earbuds so they can listen to the track together, it’s a moment where these two men who are basically strangers to each other form a bond. When these two men meet up again later in the movie under very different circumstances, Wright reprises “Brighton Rock” again. At first, it’s a song about two people coming together; now it’s a song about a relationship that’s literally falling to pieces.

In an interview with Pitchfork, the director explained how he storyboarded the film with these specific songs in mind, going so far as to choreograph car noises, gunshots, and fight scenes in time with the music. That precision is something that the film itself lampshades, when Baby (who times his own getaway drives to specific tracks) has to put their escape on hold so he can restart a track on his iPod.

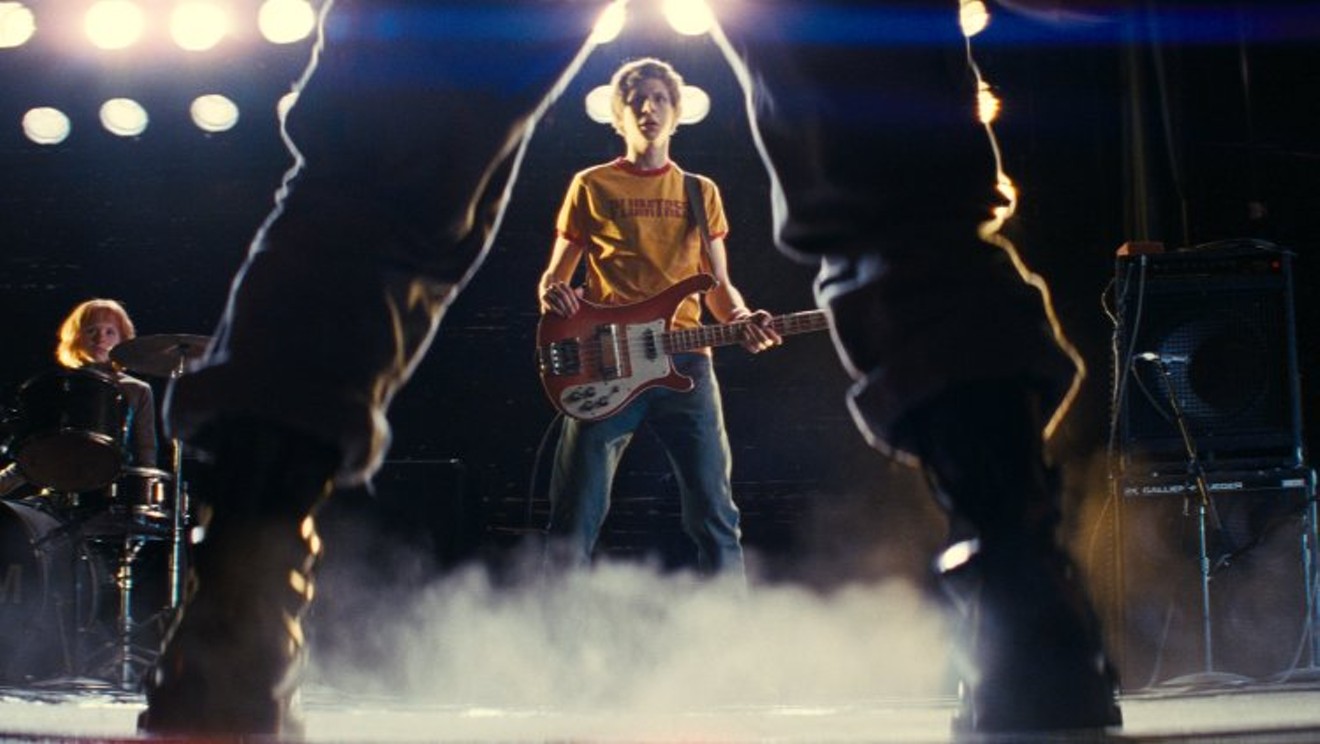

Baby Driver isn’t unique in Wright’s filmography in its obsession with music: All of his films are marked by their inventive and thoughtful soundtracks. Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (2010) is Wright’s only film to actually take place in a music world — in Toronto’s garage rock scene. In the story of a slacker who tries to win the heart of a new love by defeating her seven evil exes, Wright uses music as the backbone of the film’s many fight scenes (from a literal battle of the bands to a bass guitar duel that blows down brick walls).

Wright also uses music to add pathos to the film. Look at how he paints two different reactions to a breakup through music. When Scott dumps Knives Chau and buses home to T-Rex’s swooning, truimphant “Teenage Dream,” he’s full of excitement for a possible future with new girl Ramona. But Knives is destroyed by it, and her pain’s best expressed through Broken Social Scene’s poignant “Anthems for a Seventeen Year-Old Girl.”

Out of all his films, though, The World’s End (2013) stands as the best example of Wright’s soundtrack expertise. It’s generally considered the weakest of the Cornetto movies, a trilogy of films including Hot Fuzz (2009) and Shaun of the Dead (2004) that Wright co-wrote with Pegg. But to put things in context: A weak Cornetto movie is still better than 90 percent of anything else. It’s a film that’s aged well, revealing new depth with each viewing. It’s especially clever how Wright messes with our expectations by casting stars Simon Pegg and Nick Frost against type. For once, Pegg is the childish drunk, while Frost plays the stone-cold-sober straight man.

The World’s End is a film about how you can’t go home again. Our protagonists return to their childhood home to relive the “greatest day of their lives,” back during in the era of baggy U.K. rock like The Stone Roses. Everybody’s moved on with their lives except for Pegg’s Gary King, who’s still wearing the same Sisters of Mercy shirt he wore as a teenager. He hasn’t moved on, and the soundtrack hasn’t either. The film is full of songs from their childhood: English rock/dance crossover acts like St. Etienne, Primal Scream, and Soup Dragons share airtime with U.K. college rock cult acts like Suede, Pulp, and Teenage Fanclub.

The film’s most subtle and sneaky music cue comes towards the end of the movie. Gary and the gang retreat to a bar where they encounter an old school teacher, played by Pierce Brosnan. During a tense conversation with him, The Sundays’ gentle and lilting “Here’s Where the Story Ends” plays in the background of the bar. It works brilliantly on multiple levels. First off, it’s such a pretty and innocuous song that it serves as a great contrast to the standoff happening in the bar. It also makes sense for the setting. This is exactly the kind of inoffensive old-school pop-rock that people would listen to in a bourgeois pub. But where it gets really sneaky is in how it’s directly commenting on the action. This scene is where the story ends. This is the moment when the sinister force that’s taken over their town stops pretending to be something it’s not and comes clean. It stops telling them a story and starts telling them the truth about their situation.

Wright is a genuine music nerd. He understands how deeply fans connect with their favorite songs. In The World’s End, King might be a pathetic washout, but you get the sense that Wright thinks there’s something noble about his refusal to turn his back on the Sisters of Mercy. When the film ends with “This Corrosion” blaring, it feels like a moment of grace for the character. Wright is a big-time filmmaker, but he’s also the kind of guy who’d refused to waste a good copy of Purple Rain on a zombie.

Cult Classics is screening Scott Pilgrim vs. The World on Saturday, July 29, at Pollack Tempe Cinemas.

Editor's note: This post has been updated from its original version to reflect the correct screening date for Scott Pilgrim.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]