Bass players don’t get enough love.

The humble bass guitar keeps things moving on an even keel. It's the spinal cord for so much pop music — a literal baseline from which guitars and vocals form the hills and valleys of melody and volume.

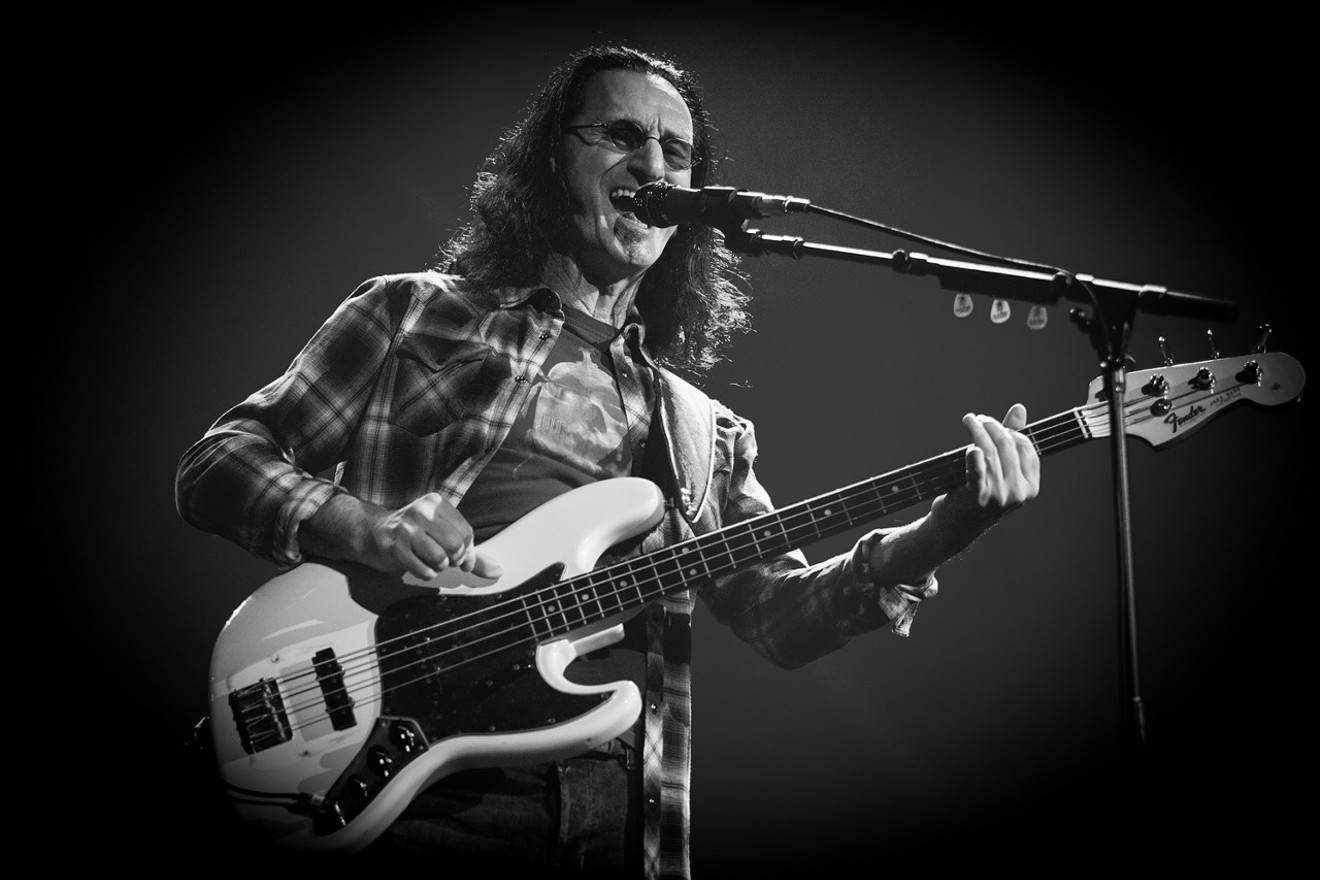

It’s often a thankless job, but there are moments when the bassist becomes the most beloved person in a band. There’s probably no better example of that than Rush's Geddy Lee.

Listen to any Rush song and two things will immediately catch your ear: Lee’s nimble, muscular bass lines, and his high-pitched vocals. Love it or hate it, NOBODY sounds like Geddy Lee on the mic, or when it comes to (in the words of Paul Rudd) "slappin’-de-bass."

The man’s love for his instrument goes beyond sheer instrumental virtuosity. He’s an avid collector of bass guitars and a one-man encyclopedia on all things with four strings.

That passion for his instrument has led to the publication of Geddy Lee’s Big Beautiful Book of Bass, in which the frontman guides readers through a fat bottom-ended wonderland. It's a dense tome packed with photographs from Lee’s extensive bass collection, and full of fascinating anecdotes about bass guitars drawn from interviews with legendary players like Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones and Les Claypool from Primus.

For Rush fans looking to get a chance to meet their hero, you won’t have to wait long. Lee is making an appearance in the Valley this weekend to do a book signing. He'll be at Changing Hands in Tempe this Sunday, November 3, at 4 and 5 p.m.

We got a chance to talk with the "Tom Sawyer" singer before his visit about his writing process, how hard it is to collect things you want to play with, and why bass players don’t get the respect they deserve.

In your interview with Rolling Stone, you mentioned that your original manuscript for the book topped out at 845 pages. What didn’t end up making the final cut?

Well, I was very luxurious in terms of the detail that I went into on each bass. And in the original draft, there were a few more basses in it than there are now. When we shot the instruments and started doing the layout, we had about 30,000 photographs… I think we all have a tendency to fall in love with our own stuff sometimes. By the time we finished laying everything out, there was a lot of detail that we thought was very important to have in there, but it made the manuscript grow to such a huge size and we weren’t objective enough to see the redundancies in there that maybe your average person would see.

I imagine most writers when they hand in their first version of a book, it’s probably fatter than the editor would like it to be. And that’s part of the learning curve, right? So sitting down with my editor and the staff at Harper Design was really quite helpful. We were very precious about each photograph and didn’t want to cut anything out, but after spending 10 days in New York with the good folks at Harper Design we were able to decide on a better balance for the book. Some of those decisions were painful for me, but I think they’re supposed to be painful.

When you were putting the book together, were you envisioning the audience for it being fellow bass aficionados? Or were you trying to appeal to the layman?

That’s the whole trick of the book. Initially, we realized that what’s important about this book is doing justice to these vintage bass guitars. I didn’t feel that there was one compendium out there that had enough variety and showed off these instruments in their true blue beautiful state. So I very much wanted it to appeal to the collectors, to the bass players, to the people that really loved the instruments and would really appreciate them, people who perhaps have wanted this kind of compendium in their lives.

At the same time, I took into account that I played in a rather popular rock band for over 40 years and there would, naturally, be interest from Rush fans and other music fans. And some of those people may not be as well-versed with the minutiae and the peculiarities that make one instrument rarer than another. So writing this book was all about juggling those things — keeping the authenticity and describing the instruments in a way that would say something to the collector while also making it fun to read for someone who’s never picked up a bass before.

There’s this perception that collectors are hands-off people that urge to keep things in mint condition. As someone who is both an avid bass collector and a musician, is it hard to resist the urge to play with your “toys?"

It’s very hard not to play with them. They’re made to be played. But everything I buy, I do play, with some rare exceptions. Some of them are better suited to remain in the case or hang on a wall. Whereas others are meant for the road — they’ve really lived a life and have been broken in, so to speak.

And those instruments are a big part of what I wanted to explore in this book. You can collect what I call “case queens.” The analogy my friend always makes is, "Johnny wanted a drum kit for Christmas, but he got a bass. So that bass spent most of its in a closet or under his bed." That, to me, is a time capsule. And for most of the big collectors, they really want those untouched, pristine instruments that have lived in a vacuum. I totally get that and I love those as well. But there’s also the instruments that have been the main source of joy and love for a player through most of their lives.

Maybe it’s a guy who owned one or two basses his whole life and he played it on the weekend while playing at bars or he took it on the road to small venues. Those instruments have earned their wounds, in a way. And some of them are absolutely spectacular to look at and beautiful to photograph.

I like to show both sides of that and, wherever I can, I try to find an instrument from the same vintage that has lived its life in a case and that’s lived its life on the road. There are a few examples of that in the book that show off two sides of the coin.

Your book is packed with interviews and anecdotes about famous bass players and their instruments. Were there any particular anecdotes that didn’t make the cut that you wish had made it in?

I could have really gone on, but there were a lot of stories that didn’t make the cut. Little bits of fascinations and minutiae. There’s one in particular: I became a little bit obsessed with the EB-3 bass that Jack Bruce had on the road. You’d very rarely see a picture of Jack Bruce playing that particular EB-3. It’s one of the early ones that has a toggle switch on it instead of the round tone switch that people have come to identify with the instrument. It became a bit of guitar archaeology for me to find pictures of him with it. And I wrote a story about it, but in the end, it got very long-winded and it went into the category of not something I think everybody will find interesting.

The analogy you used earlier about the kid who wants drums got me thinking. Bass is such a major foundational element of pop music, and yet bass players don’t get a lot of respect from the culture. It’s like that old groupie joke, “Oh, you’re the BASSIST?!” Where do you think that stems from? Why don’t bassists get the same level of respect as guitarists and drummers?

It’s a good question and it’s one that’s hard for a bass player to answer. We don’t like to think of ourselves as standing in the shadows. But I think for many, many years, in the early days before the electric bass, the bass player was the problem in a band. He had this big giant instrument that didn’t fit into the bus or station wagon very easily so it had to be tied to the roof. And there wasn’t proper application when a guy played the double bass, so you had to hope it was loud enough. So as time went on, the image of the bass player was the guy who stood in the background while the guitar played his solos and the singer showed off. I think it developed from that perspective.

It’s the farthest thing from the truth in the world of jazz because the bass player is incredibly important in any great jazz combo. They’ll solo on and on and on. In popular music, though, that wasn’t necessarily the case. When we hit the '60s, you’d get players like Jack Bruce and John Entwhistle who were daring to take their tone out of the lower range and actually intrude upon the ranges that the guitar is usually known for. Then you started seeing a different kind of bass player.

Rush inhabit this strange space in rock music. They appear on classic rock radio and have a legacy status, but the devotion of their audience and the insularity of it definitely feels like a cult band. There are a lot of casual Led Zeppelin fans, but I don’t think I’ve ever met a casual Rush fan.

Yeah, our fan base is quite unusual and I think it's because we were never a prototypical rock radio band. We didn't do short songs. We didn't encroach upon the world's top 40 very often. Every once in a while one of our songs would accidentally sneak into the top 40, but our raison d'etre was always to do long and complex, and in the view of some people self-indulgent, musical pieces. And so, as a result, people discovered Rush through word by mouth and by experiencing us live.

I think people love to have a favorite band or a favorite thing that not everybody knows about. And that engenders a kind of loyalty—that's how cult bands are. And I think that's what happened with our band.

Geddy Lee is scheduled to appear on Sunday, November 3, at Changing Hands in Tempe. Tickets are $97.29 plus fees via their website. Your ticket includes an autographed copy of Geddy Lee's Big Beautiful Book of Bass,

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18478561",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "16759093",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759092",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "17980324",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "16759094",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 24

}

]