The request, he said, came during an August 2017 meeting in Camp Verde, a small town in the geographical center of Arizona known for its annual corn festival and archaeological museum. Parks called the meeting at a middle school cafeteria to update locals on the agency’s latest project. A 209-acre stretch of land poised to become Rockin’ River Ranch State Park sits along the Verde River. The landscape includes irrigated pastures, mesquite woodland, and cottonwood banks. Bald eagles and endangered garter snakes live on the property.

The state land sat mostly unused for years, but state legislators in 2017 approved $4 million to develop the area with cabins, campgrounds, and stables. Black set a goal of opening the park in August 2018. Prior to the meeting, she prepared her staff to address anticipated concerns from Camp Verde residents.

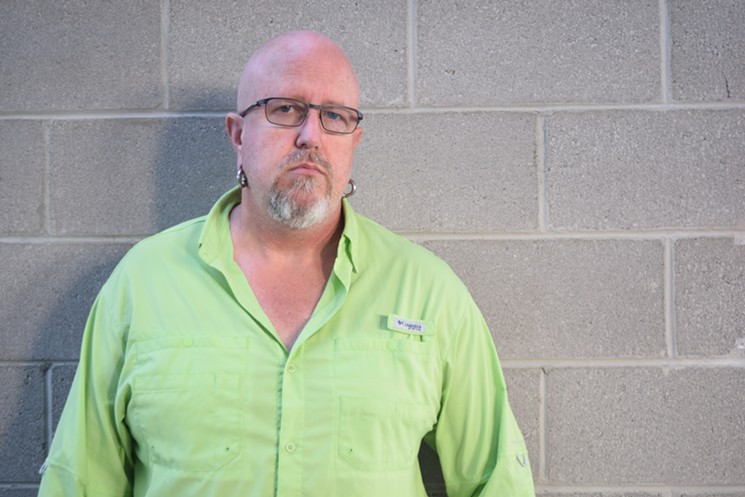

Some locals worried the park would increase traffic on Salt Mine Road. Others feared development would harm wildlife. Russell attended the meeting to address the area’s cultural heritage. He’s a 46-year-old archaeologist with thick hoop earrings and a stocky build.“We don’t talk to Indians. It just opens the door to problems.” - Parks Deputy Director Jim Keegan, according to Will Russell.

tweet this

Along with its scenic views and endangered wildlife, Rockin’ River Ranch also intersects an unexcavated antiquities site. Archaeologists believe people related to the Hohokam, the ancient central Arizona agricultural society, established a village in the area possibly before the year 750. The villagers likely dug roasting pits, storage pits, and pit houses at the site. On a ball court found on nearby private property, inhabitants would have congregated for ceremonies and games.

Surveyors did not encounter artifacts on the surface of the ranch, but any development was likely to affect artifacts underground. The discovery of ancient manmade objects — say, potsherds or stone tools or human remains — typically triggers a series of requirements under a state law intended to protect Arizona’s cultural resources. These regulations help officials figure out the historical significance of an object, whether it’s worth preserving, and how to best preserve it.

Russell planned to tell the Camp Verde residents as much. Black had other ideas. Shortly before Russell’s turn to speak, the parks director leaned over his shoulder and told him to assure the crowd that developers would not discover anything of historical significance when they started digging trenches for pipes and breaking ground for parking lots.

Russell ignored Black’s order. As he gave his planned presentation, Russell thought to himself that this meeting in a middle school in the middle of Arizona could end his short career at Arizona State Parks. He glanced at Black in the back of the room.

“She was standing with her arms folded, glaring at me. She was shaking her head and looking at me like she wanted to kill me.”

Black’s glare marked the beginning of a rift between her and Russell over the value of Arizona’s cultural resources.

Black did not respond to a request to comment.

Black and her deputy director, James Keegan, rammed through numerous developments over the next year with more regard for awards and political ambition than archaeological sites. As Black and Keegan found ways to circumvent Russell’s devotion to process, the archaeologist documented as many alleged cultural violations as he could in emails and memos.

As he did during research projects in graduate school, Russell took meticulous notes of the agency’s archaeological destruction. These notes would ultimately help lead to a criminal investigation by the state attorney general’s office — and to Black and Keegan’s downfall.

Before he became an archaeologist, Russell worked in the military and law enforcement. He later served in the Army between 1991 and 1995, working in intelligence. He served for about a decade as a police officer in Arizona, focusing on gangs and drugs.

Then, he looked for a career change. “I wasn’t feeling fulfilled,” Russell said. “I wanted to do something more with my life.”

Having previously completed a few semesters of college, he enrolled at Arizona State University in 2006 to pursue a degree in ethnography, an anthropological discipline that involves observing a culture or society over an extended period of time.

During his first semester, Russell took an introductory archaeology course — and changed his career trajectory once more.

“I was hooked instantly,” he said. “It had everything I loved about police work: taking clues, figuring out mysteries about the past.”

While completing his undergraduate program, followed by a master’s degree at the same university, Russell worked on excavations and archaeological surveys, sometimes with the help of research grants. He developed a particular interest in prehistoric tracks on Perry Mesa in north central Arizona and conducted the most in-depth study on the features to date. His research concluded that people in the prehistoric era used the site for ritual racing.

In 2016, he completed his doctoral degree at ASU in anthropology, with an emphasis on archaeology. His dissertation explored social inequality among indigenous peoples in the Mimbres region of southwestern New Mexico from about 200 to 1130 B.C.

Russell’s attention to detail stood out among faculty. Michelle Hegmon, an archaeology professor at ASU, recalls that Russell developed a system for classifying Mimbres pottery, identifying unique techniques from ancient artisans. While others might have found the work mind-numbing, Russell was enthralled.

“He looked exactly at how a brush stroke was done, how a turtle’s mouth was painted,” said Hegmon, who served on Russell’s dissertation committee.

Russell had started a post-doctoral program when the job at Parks opened up. He had considered pursuing the same position years before, but decided he wanted to finish school first. The job appeared to have everything he wanted in his work life — a mix of research, fieldwork, preservation, and public interaction. Plus, he felt a responsibility to protect the state’s heritage. His children, after all, are seventh-generation Arizonans.

Russell admired the loftiness of the agency’s mission statement: “Managing and conserving Arizona’s natural, cultural and recreational resources for the benefit of the people, both in our Parks and through our Partners.”

After a round of interviews, Russell accepted a job offer from Arizona State Parks in June 2017. Black was not involved with the interviews.

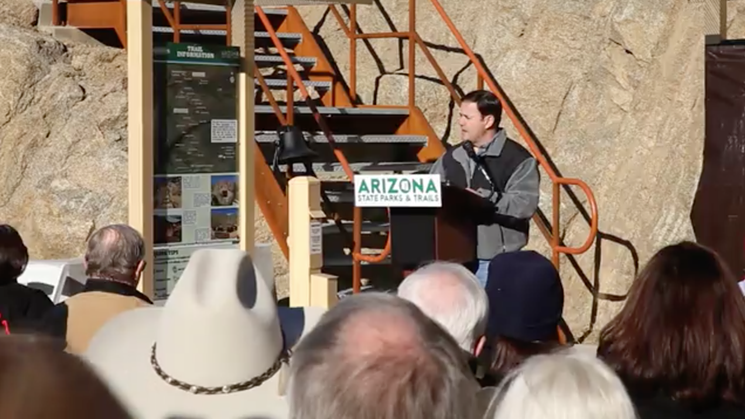

Governor Doug Ducey during the dedication ceremony at Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial State Park.

Arizona State Parks

During Russell’s year and a half at Parks, he grew angry over practices he viewed as flagrant violations of state law.

Not long after he was hired, it became clear to him that Black and her allies, especially Keegan, did not value his role as a compliance officer. Parks leaders pressured Russell to treat antiquities sites not as cultural resources in need of protection, but as obstacles to development.

Records obtained by Phoenix New Times show Arizona Parks built gardens, trails, campgrounds, picnic areas, and cabins on several archaeological sites without following procedures intended to protect Arizona’s cultural resources.

At Tonto National Bridge State Park, parks personnel cut a traditional indigenous structure known as a gowah ring in half while developing a cottage. Parks also reportedly built a garden on a site believed to be the only remaining example of Apache cultivation in the Southwest.

In one spot at what is now Lake Havasu State Park, Native Americans worked to transform stones into tools and weapons. Agency personnel approved leveling the area despite multiple warnings from Russell to avoid the site.

Parks developments disturbed both ancient artifacts and archaeological sites dating to more recent times, such as a historic road at Slide Rock State Park used by early pioneers to build a water system. Parks damaged the site while developing picnic sites. Russell has a personal connection to Slide Rock. His ancestors were among the first wave of pioneers to establish homesteads in Oak Creek Canyon.

Agency leadership showed similar disregard for present-day Native Americans, cutting them out of the development process despite state laws requiring tribal consultation. Russell recalled that Parks deputy director Keegan once told him, “We don’t talk to Indians. It just opens the door to problems.”

Keegan could not be reached for comment.

After he discovered damage to sites at Tonto Natural Bridge State Park earlier this year, Russell invited a compliance supervisor from the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community to give a cultural sensitivity training seminar at Parks headquarters north of Deer Valley. Agency leadership called its own meeting at the same time as the presentation, ensuring only a handful of employees would show up for the training.

When Russell tried to involve tribes during the planning stage of new developments, Parks cut him out, too. Managers took him off projects that he was already working on and kept him in the dark on new developments with archaeological sites, despite state law requiring his involvement. He found himself resorting to Facebook to communicate with tribal representatives after Black prohibited him from doing so through formal channels.

Russell recalled learning of a project currently under construction — Havasu Riviera State Park — from an agencywide newsletter linking to a video of development at the site. “The new park is shaping up! Both concrete launch ramps were poured and completed and then pushed into the lake,” the newsletter said.

When Russell informed the relevant tribes and federal agencies of the development, he said Keegan coerced him into signing a follow-up memorandum requesting they disregard his request for assistance. “I apologize for any alarm or unnecessary work my inquiry may have caused,” stated the memo, which Russell said Keegan wrote.

“It got to the point where I could go in there, sit at my desk, and not do anything for eight hours. I felt like every tool I had to actually make a difference was stripped away from me,” Russell said.

He became depressed. The stress drained his energy at work and affected his relationship with his two children. “Every archaeological job I had, I used to love coming into work,” he said. “I would just dread it here. I felt sick to my stomach coming in.”

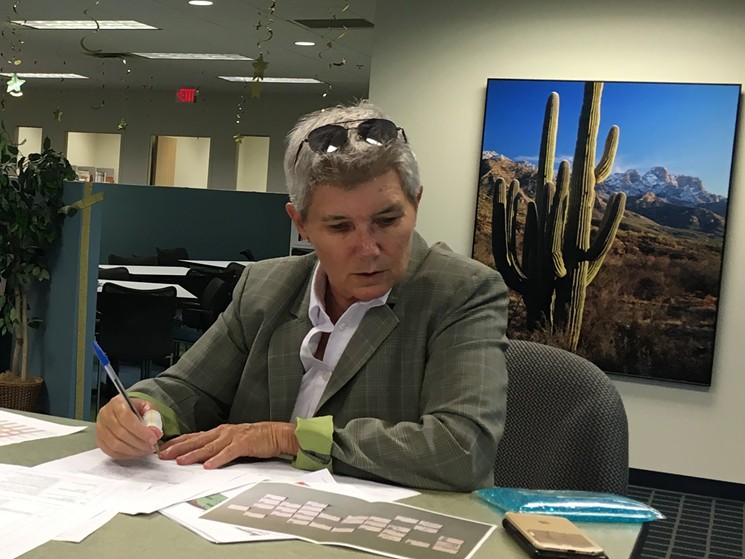

Governor Doug Ducey appointed Sue Black as director of Arizona State Parks and Trails in February 2015. Black’s new gig was a homecoming.

She previously served as the agency’s chief of operations from 1993 to 1997. After leaving Arizona, she began a two-decade career in Wisconsin, first serving as director of the state’s park system and then as the head of Milwaukee County Department of Parks, Recreation and Culture.

She developed a reputation as a hard-charging leader with a promising career. A 2007 article by Milwaukee Magazine highlighted Black’s ambitions. While discussing the park director’s career goals, reporter Susan Nasser asked Black whether she’d like to lead the National Park Service one day. “Actually,” Black responded. “I’d like to be Secretary of the Interior.”

Black’s hypothetical trail to the presidential cabinet would not lead directly from Wisconsin. Milwaukee County Executive Chris Abele fired Black under mysterious circumstances in 2012. Abele has yet to publicly state the reason for Black’s termination, telling reporters at the time. “I don’t owe you gossip.” He did not respond to New Times’ requests for comment.

Black entered the private sector for a couple of years, becoming the owner and CEO of the Milwaukee Wave, an indoor soccer team. During Black’s tenure with the Wave, a promotional merchandise firm sued her and the team, claiming they failed to pay back a $150,000 loan. The case was settled a month after it was filed, with Black divesting all ownership and management responsibilities for the team.

How Black ended up back in Arizona is not entirely clear. For most of Arizona State Parks history, a seven-member board chose the Parks director. Following changes to the hiring process, Black became the first director appointed by the governor.

Sue Black wanted to have zip lines installed at Rockin' River Ranch State Park, employees said.

Arizona State Parks

Walker lost his re-election bid in November.

From the outset of her return, Black made it a goal to win the National Gold Medal Award, an annual honor from the American Academy for Park and Recreation Administration (AAPRA). The accolade, ostensibly given to the best-managed park systems in the country, represents ultimate bragging rights in the field. Few honors would look more impressive on the resume of a politically inclined parks director.

“The gold medal was the daily topic of conversation. It dominated every meeting,” said Kelly Moffit, who worked at the agency for a combined 13 years. He retired as deputy director in 2015 due to health reasons shortly after Black’s return.

According to current and former Parks employees, the race for the medal drove many decisions at the agency, including a push to increase development across Arizona.

Black set a goal of adding 100 cabins throughout the state, up from 30 from when she started at Parks. By the time of Black’s firing, her administration had developed 29 cabins. Parks also developed 22 RV sites and 36 campsites under her directorship.

Director Black had a grand, offbeat, and sometimes ridiculous vision for Arizona Parks.

At Rockin’ River Ranch State Park, she hoped to install zip lines, according to multiple employees. Black also wanted to establish beer gardens at several state parks, including Slide Rock State Park, Patagonia Lake State Park, and McFarland State Historic Park, despite concerns from staffers that alcohol could present liability problems.

One of Black’s oddest proposals was to build a lake at Pichaco Peak State Park, in one of Arizona’s most arid regions. To develop the project, Black hoped to hire Crystal Lagoons, a Dallas-based company that creates enormous bodies of waters in places you’d least expect to find swimming holes. Staffers eventually convinced her that the project would not be a sensible use of resources.

In February 2017, the agency made its case for the gold medal in a video featuring Ducey, former Arizona Diamondback outfielder Luis Gonzalez, the late Senator John McCain, and several unnamed Parks staffers. Set to the tune of a bouncy rock track, voiceovers roll through a list of statistical claims racked up under Black’s directorship: four new state parks, 50,000 student passes, 300,000 volunteer hours.

Parks won the gold medal in September 2017. Black ordered 10 replicas at $720 apiece and delivered them to the Arizona House, Senate, governor, and several state park offices across the state.

In an emailed statement that did not address Arizona State Parks’ controversies, a spokesperson for AAPRA said this month that the organization stands by its decision to award the agency the Gold Medal.

A replica Gold Medal displayed in the Capitol was removed last week.

The Gold Medal award, once displayed at the Arizona Capitol, was removed after Sue Black's firing.

Elizabeth Whitman

In June, when Ducey’s administration opened an investigation of Black’s treatment of staff — the third since 2015 — employees became hopeful for a leadership change. Investigators with the Arizona Department of Administration (ADOA) spent three months stationed in the office, interviewing dozens of employees for hours at a time.

Parks staff made numerous complaints against Black and Keegan during this time, including allegations of mistreatment of employees, forced volunteer work, violations of the Family Medical Leave Act, violations of procurement code, misuse of federal funds, destruction of evidence, and fudging of numbers on awards submissions.

During those summer months, Russell first blew the whistle on the alleged archaeological damage, handing investigators hundreds of pages of documents. He wrote white papers outlining his concerns for Bret Parke, a top Ducey official who was temporarily installed as Parks deputy director while the ADOA conducted its investigation.

After interviews were wrapped up in September, Russell waited. And waited. Weeks went by. The Ducey administration did nothing. Multiple employees who came forward to the ADOA with allegations of wrongdoing described a similar feeling of frustration.

In mid-October, Russell told ADOA investigators he could no longer tolerate the work environment at Parks. “I would honestly consider working at Jack in the Box,” he told them.

Days later, he received an offer from the Arizona Department of Transportation for a compliance officer position, the same work he did for Parks. He accepted the job. On October 15, his last day of work at Parks, Russell wrote a department-wide email explaining why he was leaving. He concluded the note with a rallying cry to his disaffected colleagues.

“Things will change,” Russell wrote. “The mission will eventually emerge from the shadow of revenue and ego. I hope mine is the last dream to be crushed by this place. In the meantime, be good to each other. Fight the good fight. Hold your heads high, stay true to yourselves, and know that you are stronger than they think you are.”

In a still from Arizona State Parks' video submission for the Gold Medal award, staff pose outside the agency's north Phoenix headquarters.

Arizona State Parks

Russell had already gone to the press. On October 23, New Times published a story revealing the alleged archaeological damage at Lake Havasu State Park, setting off a cascade of events that vindicated the archaeologist. The day after New Times published its story, the Ducey administration opened an investigation on the matter.

Five days later, the Arizona Republic revealed additional allegations, including potential cultural violations at Tonto National Bridge State Park, Slide Rock State Park, and Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial State Park.

Four state legislators comprising the Indigenous Peoples Caucus called on Ducey to fire Black and demanded that Attorney General Mark Brnovich launch a criminal investigation.

“These acts of destruction, if substantiated, would violate the Arizona Antiquities Act and would be an affront to all indigenous peoples in Arizona, the United States and the Americas,” stated a letter to Ducey signed by State Senator Jamescita Peshlaka and State Representatives Sally Ann Gonzales, Eric Descheenie, and Wenona Benally.

One day after Ducey received the letter, New Times received an internal Parks memo written by Russell showing that his concerns about agency practices extended beyond alleged cultural destruction.

Russell’s memo recounted a conversation he had with deputy director Keegan. Keegan told him he met with a lobbyist for Copper Resolution regarding a potential gift of land while the company was planning to dump hundreds of millions of tons of mining waste near Boyce Thompson Arboretum State Park, raising conflict of interest questions for an agency already mired in allegations of wrongdoing.

New Times sent questions to the Ducey administration regarding the memo on November 1. Hours later Ducey placed Black and Keegan on administrative leave and Brnovich announced a criminal investigation of Parks personnel.

Two weeks later, following his re-election, Ducey ousted both Black and Keegan from office.

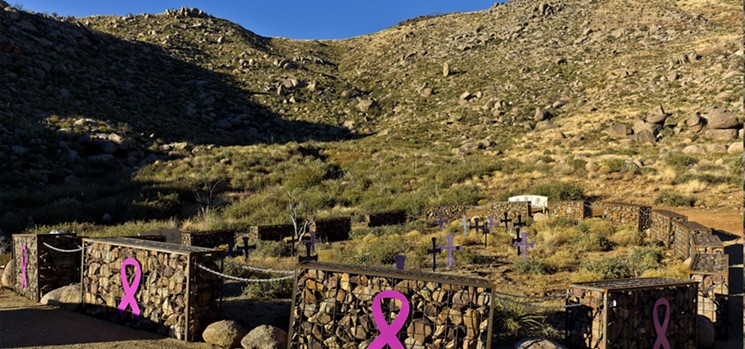

The Granite Mountain Hotshots Memorial, dedicated to the 19 firefighters who died on June 30, 2013, in the Yarnell Hill Fire, became Arizona’s newest state park in 2016. Marked by a tiny parking lot directly off Highway 89, the park consists of a strenuous trail that winds up a mountainside before descending to the tragedy site, where gabion baskets filled with rocks encircle 19 metal crosses, one for each firefighter who perished.

“May this always be a sacred place for this community,” Ducey said during a dedication on November 29, 2016, the day before the park opened.

It may have already been a sacred site for another community. The 3.5-mile memorial trail happens to intersect with an ancient trail that archaeologists believe could have been used by ancient Native Americans as part of a transportation network. A pottery fragment found about 70 meters from the site helps make the case that indigenous people charted their own route through the area centuries before modern-day visitors hiked up Granite Mountain in somber reflection.

Parks appears to have developed over the ancient trail despite warnings from Paula Pflepsen, an archaeologist who served as a compliance officer before Russell. Pflepsen had recommended that the memorial trail avoid the archaeological site. The State Historic Preservation Office, a division of Parks, concurred with Plfepsen’s finding.

The development suggests that the agency was failing to comply with cultural regulations earlier than 2017, and that the extent of archaeological damage under Black may never be known.

Russell’s first suspicion of a potential violation at the memorial site came in March 2018, when he conducted a routine review of the project as Parks prepared to conduct maintenance on the trail. During the summer, with Bret Parke serving as deputy director, Russell felt empowered to perform the tribal consultations he couldn’t do under Black.

He reached out to 11 tribes that have expressed a connection with the area where the memorial park currently sits. An archaeologist who works for the Yavapai-Prescott Indian Tribe responded that he’d like to visit. So did Kurt Dongoske, a nationally regarded archaeologist who serves as a historic preservation officer for the Pueblo of Zuni in western New Mexico.

Dongoske explained in an email on July 31 to Parks that trails are important to Zuni culture because they connected the tribe to water, plants, and animals within the tribe’s cultural landscape.

Like other tribes in the Southwest, archaeologists believe the Zuni took advantage of long-distance trade networks in the region.

“[Trails] tell about Zuni history in those areas where Zuni ancestors settled during their journey to the ‘Middle Place’ and they continue to maintain a vital spiritual connection between the Pueblo of Zuni and those very important places,” Dongoske wrote.

He’d been working on a project with Octavius Seowtewa, a member of the Pueblo of Zuni, to identify trails that might have been used by prehistoric Zuni people. They surveyed sites across the Southwest, from Gallup, New Mexico, to Yuma. They hadn’t had a chance to see the Granite Mountain site.

Seowtewa learned of Black and the Parks department’s alleged crimes against archaeological sites through an article sent to him by a friend.

“I texted my friend back and said Native people, not only in the United States, should get together and condemn this person that is destroying our way of life and way of identifying who we are,” he told New Times.

He plans to soon walk the site on Granite Mountain and make a record of the trail.

Or at least what’s left of it.