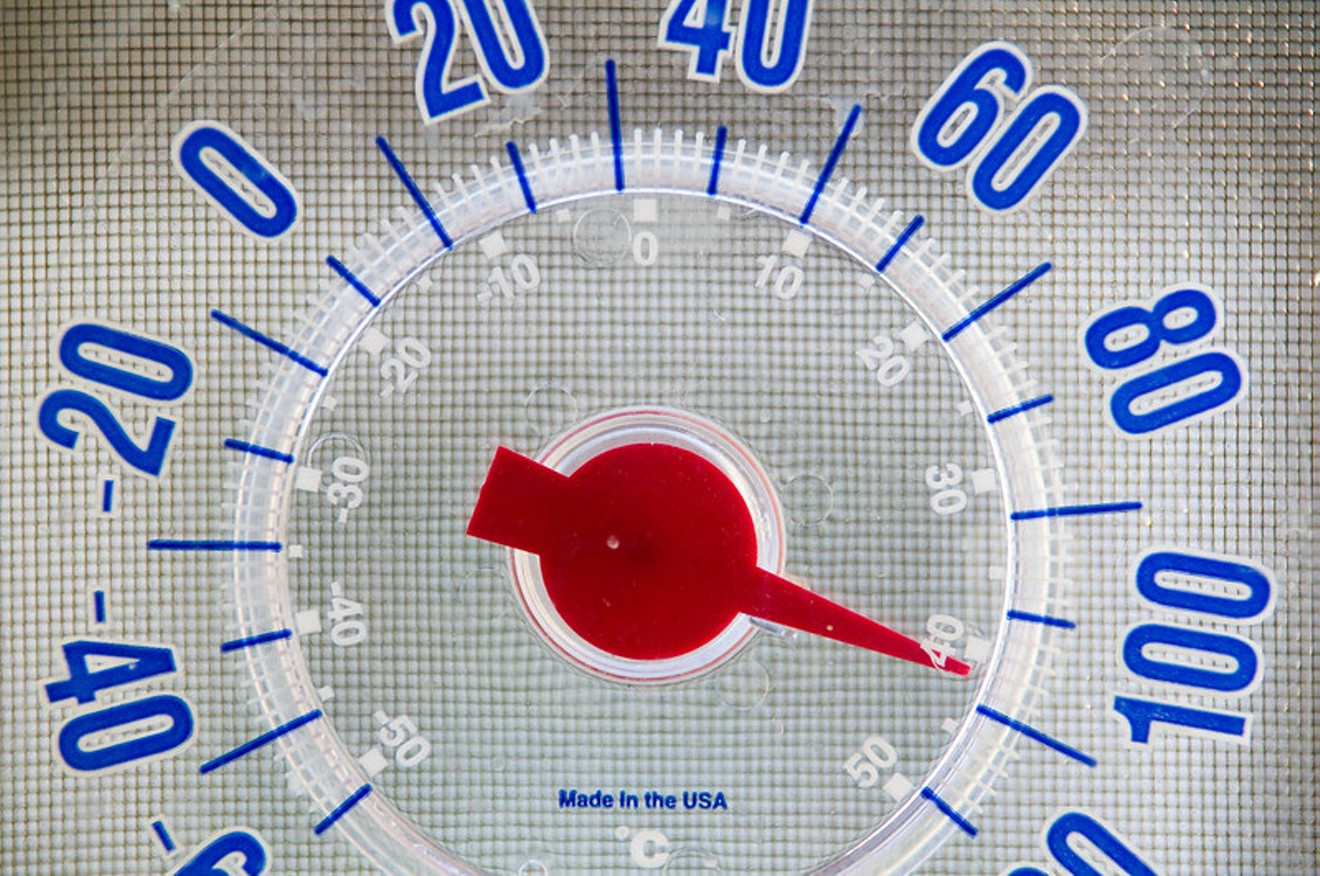

The working threshold in the Corporation Commission's draft rules is 105 degrees Fahrenheit, meaning that utilities would not be allowed to cut power to customers when temperatures are higher than that, even if the customer has a delinquent account.

Residents, activists, and experts say the limit should be lower — many say 95 degrees — for people's health, safety, and lives. Without electricity, people cannot power the air conditioning that the Valley's triple-digit summers render a necessity.

Those pushing for a lower threshold argue that even a few degrees can make a life-saving difference. But policymakers have not solicited input from the public health experts and scientists who have studied these nuances, said Stacey Champion, a local activist who is vocal about both utility rates and the problem of heat-related deaths.

"It is absolutely vital to the health and safety of Arizonans that the permanent utility termination rules, as well as any future legislation, be data-driven and climate-specific to prevent as many deaths as possible," Champion said.

Last session, she worked on a bill, SB1542, that used 90 degrees as the point at which utilities could not disconnect service. Champion said she chose 90 degrees after reviewing state-specific data. (The bill, which was never assigned to committee, did not become law.)

Elected officials should "utilize the expertise of our public health and science community so these rules and policies can be meaningful, while also protecting our most vulnerable residents," she added. "To date, that hasn't happened."

A commission spokesperson avoided answering direct questions from Phoenix New Times about whether regulators had reached out to scientists or other experts.

"Commission Staff is committed to modifying the existing rules in a timely fashion," Nicole Capone wrote in an email. "We are still looking for a date that would accommodate all of the Commissioners and interested parties for the next stakeholder meeting. We will make sure all interested parties have the opportunity to participate (including public health experts)."

In September, Champion submitted a letter to the Corporation Commission lamenting the fact that "no public health professionals or the science community" had been asked to participate in the process of developing disconnection rules. Regulators have already held two workshops soliciting input from stakeholders like utilities, which have a vested financial interest in looser disconnection rules.

Her letter included a list of 10 experts from both Arizona State University and state and county health departments. No one from the Corporation Commission has contacted the seven ASU researchers, those researchers confirmed.

Dr. Rebecca Sunenshine, medical director for disease control at the Maricopa County Department of Public Health, said in an email that the Corporation Commission would typically request subject-matter expertise from another state agency, like the Department of Health Services. "We would not expect the Corporation Commission to consult a county-level agency on this issue," she said.

Chris Minnick, a spokesperson for the state health department, said the Corporation Commission had not been in touch. "We have not been involved at all, as far as I know," he said.

A decade's worth of data on indoor heat deaths, which Champion submitted to the Corporation Commission in late September, show that people can die of heat or heat-related problems indoors well before outdoor temperatures hit 105 degrees.

Of the 422 people who died indoors of heat-related causes from 2006 to 2017, 30 percent died when outdoor temperatures were 105 degrees or below, those data show.

That data, and the graph above, were compiled for Champion by David Hondula, a senior sustainability scientist at ASU, one of the people on her list who has not heard from the Corporation Commission. He confirmed that he had not heard from regulators there.

Maricopa County has a great deal of local expertise on heat and public health, Hondula told New Times, and as far as he could tell, officials at the Corporation Commission aren't tapping into that knowledge.

"That is frustrating, as a scientist, knowing that we could contribute to the decision-making process," he said. "We're researching the heck out of this problem," he added, referring to experts at ASU, local departments and agencies, and the National Weather Service.

That research doesn't provide clear answers about what's a safe threshold, but it can help regulators with the delicate calculus of deciding how much risk they're willing to expose people to, Hondula said.

"There's not going to be a magic threshold, where nobody dies indoors," he explained. Instead, decision-makers are going to have to make a judgment call, a sort of cost-benefit analysis of disconnection, because the lower the temperature threshold, the more lives are saved, he said. Based on existing research, he suggested a threshold in the "low 90s or below."

Hondula also suggested that a disconnection ban would likely have other benefits, such as fewer emergency room visits for heat-related illnesses, or less stress for low-income families struggling to pay their utility bills during the summer — areas ripe for consideration and study, he pointed out.

Liza Kurtz, another ASU researcher on Champion's list, who studies extreme heat and power outages and works closely with Hondula, expressed interest in being involved.

"Hopefully we can support them with some data in their decision-making around extreme heat thresholds," Kurtz said.

Heat becomes dangerous when the human body can no longer cool itself properly, starting with heat illness and resulting, at its most extreme, in organ damage and death. The effects of such heat varies from person to person, depending on their age, weight, hydration levels, drug or alcohol use, underlying health conditions, and other factors, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

So far, Arizona regulators have suggested several different temperature thresholds, and it's not entirely clear how they arrived at them.

Initially, CorpComm staff suggested a threshold of 95 degrees, according to memos filed at the end of July. That temperature would comport with national norms for shutoff protections in extreme heat. Later, it was pushed up to 105 degrees, existing draft rules show.

Most recently in mid-October, Chairman Bob Burns suggested changing the threshold to a heat index of 99 degrees Fahrenheit or above. A heat index represents how the air feels to a person, and thus differs from actual temperatures depending on humidity.

For example, a heat index of 99 degrees could represent a day when the relative humidity is just 5 percent and actual temperatures hit 107 degrees — a likely scenario during Phoenix's hot, dry summers. The same heat index could represent a day when temperatures are 85 degrees and the relative humidity is 85 percent, according to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.

If the rules, as drafted, were to pass, Arizona's threshold would be the highest in the country among the few states with temperature-based shutoff protections. Arkansas, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, and New Jersey bar shutoffs above 95 degrees, and Oklahama at 103 degrees, per a list compiled by the Department of Health and Human Services.

Dozens of vocal Arizona residents have also signed form letters, which were sent to Burns, opposing the working standard of 105 degrees, saying it's dangerous.

"Heat kills and 105 degrees is too hot!" state the letters, which were coordinated by the state AARP, pointing out that 105 degrees is almost seven degrees above the temperature of the human body. "Such heat can and has killed," they add.

“This isn’t about utility convenience," said Steve Jennings, an associate state director at AARP Arizona. "It’s not about, there’s a bunch of people that don’t want to pay their bills, so they don’t pay… We’re talking here about public health.”

In testimony at a workshop at the end of September to discuss the proposed changes to shutoff rules, John Coffman, an expert witness for AARP, urged commissioners to use 95 degrees, not 105.

"We know that Arizona gets hotter than most other states, but that doesn’t change the physiological dangers of extreme heat upon the human beings who rely on utility service in this state," he said."I would suggest that all members voting on this issue spend 24 hours in a room with no power when it's 105 degrees...then decide if that is the magic number." - Linda Depaolo

tweet this

In his testimony, to show how serious a problem heat can be, he included CDC data comparing the numbers of death by extreme heat in Arizona each year with deaths from hurricanes throughout the entire U.S.

In every year since 2008 except for 2017, the number of heat deaths in Arizona alone has exceeded the number of people nationwide who died because of hurricanes, the data showed. Arizona is one of three states with the highest number of heat-related deaths; the other two are California and Texas. California does not have temperature-based termination protections, while Texas prohibits residential disconnections during heat advisories.

Those figures don't include the thousands of visits to the emergency room each year in Arizona for heat-related illness. The CDC says too that the number of heat-related deaths is likely an underestimate, because deaths due to heat are "often misclassified or unrecognized."

Linda Depaolo, who also commented in favor of a 95-degree threshold, weighed in separately with an email to the Corporation Commission. She offered an idea, to help those who make the rules understand the real-life implications of their decisions.

"I would suggest that all members voting on this issue spend 24 hours in a room with no power when its [sic] 105 [degrees]...then decide if that is the magic number," Depaolo declared.

Regulators at the Corporation Commission have been weighing changes to current shutoff rules for several months. The changes were sparked by the news in mid-June that 72-year-old Stephanie Pullman died in her home after Arizona Public Service cut her power on a 107-degree day. She was delinquent on her account by $51.

A week after the story broke, regulators imposed an emergency moratorium on all utility shutoffs through mid-October. The debate over 95 or 105 degrees comes as it works to develop permanent rules governing when and how utilities can disconnect customers and when they can't, including during extreme weather.

The latest data from APS, the state's largest utility, show that nearly 90,000 residential accounts were delinquent as of October 14, the day before the moratorium ended. Of those, roughly 10 percent were classified as low-income customers.

All told, this month, APS customers owed the utility roughly $30 million, which is triple the amount they owed in October 2018. But, as one consumer advocate has noted, APS had a daily revenue of about $10.1 million in 2018.

Prior to the emergency moratorium, Arizona regulations did not prohibit utilities from cutting power to people during hot weather.