Before she was elected mayor of Phoenix, Kate Gallego was responsible for the demise of Lake Buchanan.

Buchanan Street, located one block south of Talking Stick Resort Arena, would flood whenever torrential monsoon rains swept into Phoenix. Thanks to the slope of the road and the absence of a storm drain, the road would transform into a small lake. Water would pour into neighboring buildings, causing a tremendous headache for businesses. The city of Phoenix used to send a truck to pump the water out of the street for hours and discharge the water into a storm sewer, only to do it again the next time the rains returned.

The diluvian phenomenon came to be known as Lake Buchanan to locals like Brian Cassidy.

After years of flooding, Cassidy, an architect with an office on Buchanan Street, showed photos of the problem to then-Councilwoman Kate Gallego in 2015. Her no-nonsense response: “We can’t have that. We’ve got to fix that,” he recalled.

A few months later, at Gallego’s request, the city and the county’s flood control district moved forward on a project to install a storm drain that could flush out the water on Buchanan Street. Cassidy was impressed. He still isn’t quite sure what Gallego did to solve the problem. “I don’t know how they make the sausage some days in the back room, but it got done,” he said.

Letting the street flood on a regular basis didn’t make sense. After all, the city was trying to reinvent the hardscrabble neighborhood as a center of new development. Gallego understood that, Cassidy said, and saw the need for an infrastructure solution in the neighborhood on the downtown edge of her district. “She found the fix rather than the Band-Aid,” he said.

Draining Lake Buchanan may not register as Gallego’s biggest accomplishment during the years she represented District 8 on the Phoenix City Council. For her most important achievement, she points to the city’s equal-pay ordinance, which passed unanimously in 2015 and changed city law to match the federal Equal Pay Act.

But the episode underscores what Phoenix residents might see during Gallego’s time as mayor, based on accounts from people who know her: a policy wonk’s attention to detail, plus a keen political awareness of what her constituents expect from the city, and, by extension, from her.

Gallego’s quick response to the situation on Buchanan Street was rewarded several years later during her run for mayor.

Cassidy, the chairman of a nonprofit Warehouse District business association, supported Gallego and donated to her campaign. At a get-out-the-vote rally in downtown Phoenix days before the election, Cassidy recited the saga of Lake Buchanan to the assembled supporters.

His underlying message — Gallego the focused, prepared problem-solver — evidently resonated with voters during the special election on March 12.

The 37-year-old Gallego was scheduled to be inaugurated today, March 21, after crushing her opponent, firefighter and former City Council colleague Daniel Valenzuela, with nearly 60 percent of the vote. She is the second elected female mayor in Phoenix history, following Margaret T. Hance, who served from 1976 to 1983. Phoenix is now the fifth-largest city in the U.S., and Gallego stands out as the only woman leading one of the nation’s top 10.

She will have to run again in November 2020 if she wants to serve a full four-year term now that she has won the special election to fill the remainder of former mayor Greg Stanton’s term, which ends in April 2021. Stanton resigned last year to run for Congress and won the open seat in Congressional District 9.“We have to deliver. The street system has to work; when you call 911, we have to respond; when you turn the tap, water has to come out.” – Kate Gallego

tweet this

If she wins re-election and remains the mayor for the maximum of two four-year terms allowed by law, Gallego could steer Phoenix for a decade. She may have a long political career even after leaving the mayor’s office. But Gallego is mum on her political future when there are municipal issues she can address today.

“I love local government,” she told Phoenix New Times in late January, during the final stretch of the campaign. “I feel like you’re the closest to the people you represent, and that not only can you get things done every day but you have to get things done every day.”

She contrasted city government to the morass at the federal level, where years can go by before a major piece of legislation advances. At the City Council, it’s standard to vote on 100 items at a single meeting, she said. If the city of Phoenix shut down for 35 days, as the federal government did last year, there would be “chaos,” Gallego said.

“We have to deliver,” Gallego said. “The street system has to work; when you call 911, we have to respond; when you turn the tap, water has to come out.”

People who know Gallego like to say she is “the smartest person in the room.” They describe Gallego with this phrase so regularly, one wonders if they agreed, city-government style, during an open meeting to always use the cliché.

On the other hand, sometimes people reach for clichés because they’re true.

As a member of the City Council, Gallego was known to be attuned to granular policy details. She has a bachelor’s degree from Harvard and an MBA from the Wharton School, plus a unique work history: Gallego previously worked for the Salt River Project, where she examined environmental policy, renewable energy, and economic development.

But Gallego will face mounting challenges as Phoenix’s mayor. She will have to juggle public-safety funding, a growing affordable housing crisis, heat and drought, and the city’s multibillion-dollar pension debt. An initiative on the ballot this summer will challenge light-rail expansion. Under the interim mayor, the council’s work has been scattershot. Crucial issues such as the south Phoenix light-rail extension, a water rate increase, and the city’s budget have nearly unraveled.

Gallego can be accurately described as a wonk. In light of the problems ahead, Phoenix may need one.

Kate Gallego declares victory in the mayoral race at a Crescent Ballroom party on March 12.

Joseph Flaherty

Kate Widland was born in 1981 in Albuquerque, one of two kids raised by attorneys Jim Widland and Julie Neerken. As a high school student at the private, rigorous Albuquerque Academy, she played softball as a pitcher and second baseman. In her spare time, Gallego started an environmental club at her school and organized Earth Day projects.

“I don’t think it ever crossed my mind that she would be running to be mayor of Phoenix,” her father said. “I thought she would do something where she showed leadership, it just never dawned on me that she would come to Phoenix and run for mayor.”

As a senior in high school in the year 2000, the EPA recognized Gallego and a classmate with the President’s Environmental Youth Award because of their conservation efforts. A grinning Gallego was photographed for the local newspaper next to a captive hawk the students invited to campus for an Earth Day demonstration. “It’s just really important to me to work for the environment,” Gallego told the Albuquerque Journal at the time.

The same year, Gallego was honored as a Presidential Scholar, got into Harvard, and graduated from high school as the valedictorian.

As an undergraduate, Gallego majored in environmental studies. It was at Harvard where she met her ex-husband, Congressman Ruben Gallego. In a story recounted in print many times, Gallego met Ruben at a fraternity-sponsored date auction for charity. In 2008, he proposed to her in a stunt at the Democratic National Convention in Denver; he had the Arizona delegation hold up signs asking her to marry him. They wed in 2010.

After moving to Arizona in 2004, she got involved in Democratic politics. Gallego worked for the Arizona Democratic Party during the 2004 election, and later worked at the Arizona Office of Tourism under Governor Janet Napolitano.

In summer 2005, Gallego started working for the quasi-municipal utility Salt River Project on renewable energy programs, water rights, and later, economic development and strategic planning.“I think she had a deeper way of looking at things, and I’m not sure why that was. I think that’s just Kate." – Kathy Knoop

tweet this

“She brought some bright ideas to the team,” said her colleague Kathy Knoop, a principal environmental scientist at SRP who used to work at the Agua Fria Generating Station. “And she brought a different way of looking at things — more so than somebody who’d spent their last 12 years at a power plant.”

As part of a policy analysis group at SRP, Gallego evaluated how federal and state environmental legislation, such as proposals to deal with renewable energy or greenhouse gases, would affect the utility and its customers. According to Knoop, Gallego had an ability to take a 360-degree view of SRP’s ideas, like installing solar panels on school buildings. Gallego suggested the program would show students how the technology worked and save money for the schools at the same time.

“I think she had a deeper way of looking at things, and I’m not sure why that was. I think that’s just Kate,” Knoop said.

While working for SRP, Gallego earned an MBA in 2012 from the University of Pennsylvania’s prestigious Wharton School on weekends through the school’s remote program based in San Francisco. Her economic development work at SRP gave Gallego insight into what companies value when moving to a new location, especially companies with complicated water and energy needs. But Gallego felt a greater calling for public service which would eventually motivate her to quit her job with the utility.

Gallego could have left SRP for the private sector and earned more money, but instead she chose to pursue a seat on the Phoenix City Council, Knoop said. “She couldn’t really give it her all when she was working here,” Knoop said.

Her years at SRP were also “a time period where I spent a fair amount of time complaining about my elected officials,” Gallego said. Phoenix, she thought, could do bigger and better when attracting new businesses.

“We didn’t need to always settle for a call center with no health-care benefits,” she said. “But could we do high-wage manufacturing in this community, make more things? Could we invest in training programs that would make us competitive when businesses are deciding? Can they grow here – do they have the talent pool of great, educated folks to hire?”

She did the complaining. Then she decided to run for office to see if she could do something about it.

‘YOU CAN’T OUTWORK HER AND CAN’T OUTSMART HER’

District 8 of the City Council encompasses a diverse cross-section of Phoenix. The Council district includes parts of Phoenix’s downtown core, Sky Harbor International Airport, a long stretch of the Salt River, and historic African-American and Latino communities in the neighborhoods that lead to South Mountain.

It was on these streets where Gallego made her first real foray into politics, running to represent the district in 2013.

In a contentious campaign, Gallego outmaneuvered pastor Warren Stewart in a runoff election to replace then-Councilman Michael Johnson, breaking a tradition of African-American representation in the district and becoming the first Anglo politician to win the seat in four decades.

At times, the campaign dynamic was uncomfortable.

“There were a lot of attacks made about her pretending to be Hispanic, when we put her picture on everything. We definitely were very honest and forthcoming,” said Lisa Fernandez, a Phoenix political consultant and Gallego’s 2013 campaign manager. “She got attacked for taking her husband at the time’s name.”

Fernandez met Gallego in 2006 through local Democratic Party politics, and has worked on campaigns for both Kate and Ruben Gallego, as well as Stanton. Fernandez remains a Gallego confidant and friend. She is also part of the Arizona Democratic machinery in her own right, the daughter of House Democratic Minority Leader Charlene Fernandez.

She used vacation days to volunteer her time unpaid for Gallego’s mayoral campaign at the end of the race, Fernandez said. Recently, someone described Fernandez as the head of Gallego’s “kitchen cabinet,” she said, referring to the informal group of advisers who often surround a president.

When they met, Fernandez didn’t expect Gallego to run for office. “I thought Kate was going to run something,” Fernandez said.

Gallego’s intelligence is on display, Fernandez said, when she asks smart questions in response to a policy discussion, clearly thinking five steps ahead. How is Phoenix trying to solve the problem at the moment? Are other cities doing it better? “She’s always thinking,” Fernandez said.“There were a lot of attacks made about her pretending to be Hispanic, when we put her picture on everything. We definitely were very honest and forthcoming." – Lisa Fernandez

tweet this

With their respective political careers on an upward trajectory, Kate and Ruben Gallego made an unexpected announcement in December 2016: The political power couple was splitting up. When they announced their sudden divorce, Gallego was pregnant with their first child. Since then, the two have shared no details on what prompted the split. (Ruben Gallego did not respond to an interview request.)

Today, Kate and Ruben Gallego are advancing on separate tracks in the Democratic Party. Ruben has all but announced his bid for the party’s U.S. Senate nomination in 2020. They share custody of a 2-year-old son, Michael, who has made appearances during the mayor’s race and in the halls of the U.S. Capitol. “Our son is by far the most popular Gallego,” she said.

Fernandez said the two have a great approach to co-parenting Michael. The close association with Ruben does not bother Kate, she said. Nevertheless, from her vantage point as a friend to both people, the divorce was difficult to watch.

“You never want to see people unhappy or going through things,” Fernandez said.

Because Ruben won a seat in the Arizona House of Representatives in 2010, Gallego says she faced challenges when launching her own political career three years later. When she ran for City Council, Ruben was already an elected official with his own political profile, but a different political style and priorities.

“I heard from a lot of people that they thought he would just be making all my decisions and telling me what to do, which was really frustrating,” Gallego said. “I feel like I have a lot of expertise in this area and a lot to offer. We are both very different people and I now think people appreciate that, that I have my own record and my own leadership style.”

She paused for several seconds. “But I did feel like I needed to come out of his shadow,” Gallego said, after a brief silence.

During her time on the Council, Gallego sought to expand the public transit system, enact a sexual harassment policy for elected officials, and shed light on groups spending money to influence city elections.

Gallego co-chaired the 2015 campaign backing Phoenix’s Transportation 2050 plan and a related referendum, Proposition 104. During the election, Phoenix voters authorized a sales tax to be used to bankroll the construction of light rail, improve bus routes, build sidewalks, and repair streets.

And last year, Gallego championed a ballot measure to require people or groups spending money to influence a municipal election to disclose donations above $1,000 as a way to fight back against independent expenditure groups that rely on hidden “dark money” contributions. Led by Gallego, the City Council referred the measure to voters as Proposition 419. In November, Phoenix residents approved the change overwhelmingly to amend the city charter.

However, the Arizona Legislature approved and Governor Doug Ducey signed into law a measure last year banning cities from enacting these dark-money ordinances. Because of the state legislation, the fate of Prop 419 is unclear. A spokesperson for the governor said the Phoenix charter amendment remains under review by the office’s legal division.

People familiar with Gallego’s work on the council describe her as a policy maven who listened carefully to constituents and could be bulldog-like when securing resources for people in her district. Gallego’s hyper-focused personality occasionally made life difficult for her staff when they tried to keep up.

“She’s not somebody who is, like, ever gonna get an award for most gregarious politician in the world."

tweet this

“It’s challenging, because you can’t outwork her and can’t outsmart her,” said Gallego’s former chief of staff Geoff Esposito, a lobbyist who worked for her district office between October 2017 and February 2018.

Prior to meetings or council hearings, Esposito would take a long time to prepare in order to be able to brief Gallego on the issues, only to walk into a meeting with Gallego and find she already knew every detail. “It always made me feel good when I could provide something that Kate had not already thought of,” Esposito said.

And although Esposito said Gallego set clear expectations for her staff, she was an agreeable boss.

“She’s very nice, which is not always something that you find in elected officials,” said a former Gallego staffer, who was not authorized to talk about the election by his non-governmental employer.

Despite her intimidating academic credentials, Gallego also happened to be a boss who managed her council office professionally without seeming stilted. Gallego dives into policy work and enjoys the details, even if she might seem wonky compared to other candidates, he said.

“She’s not somebody who is, like, ever gonna get an award for most gregarious politician in the world,” he said. “So folks might read certain things into that, but in reality, she is somebody who, I think, has fun doing the job.”

But, he was careful to note, Gallego’s analytical approach didn’t stop her from connecting with people in the community. Gallego was highly engaged with the refugee community in her district, as well as the Somali Association of Arizona, he explained. “That was not the thing that somebody like me, as a political adviser, should be advising her to spend her time on,” the staffer said. “But it’s absolutely what she spent her time on.”

According to another former Phoenix City Council staffer, who asked to remain anonymous in order to speak candidly about the race, Gallego’s command of issues exceeded not only her fellow Council members, but also most of the staff in City Hall. Behind closed doors, Gallego asked thoughtful, tough questions, he said.

“She is exceptionally smart,” the former staffer said. “We have these big packets every week for the council meetings that, you know, can range from 200 to 450 pages long, depending on the meeting. She read every one of them,” he said, laughing as if in disbelief.

Supporters cheer on Kate Gallego at a get-out-the-vote rally on March 7 in downtown Phoenix.

Joseph Flaherty

The final days of the mayoral runoff turned nasty as two young, ambitious candidates from the Democratic Party sought to elbow past one another in an ostensibly nonpartisan city election.

The runoff election pitted Gallego against Valenzuela, a firefighter in Glendale who was first elected to the Phoenix City Council in 2011. During the first mayoral vote in November, no candidate secured the majority needed to avoid a runoff. Before the March election, Valenzuela adopted a team of advisers who previously had worked for the late Senator John McCain. He and his allies hammered messages geared toward Phoenix’s more conservative voters.

Valenzuela repeatedly stated his commitment to public safety, and said the city had hamstrung its police and fire departments by not hiring more personnel.

Valenzuela’s supporters in the police and firefighters unions went after Gallego aggressively for her City Council record on public safety. At one point, the Arizona Police Association paid for an advertisement featuring the union president, who said he was begging viewers not to vote for Gallego “from the bottom of our hearts in public safety.”

One week before the election, a mysterious independent expenditure group named Advancing Freedom, Inc. bought two prominent ads in the Arizona Republic encouraging residents to vote for Valenzuela, one above the fold on the front cover and another on a full page, listing his endorsements. A mailer ad from the group referred to Valenzuela as the “conservative choice” for mayor – a bizarre way to describe a Democrat whose positions closely matched those of his opponent — and compared Gallego to Hillary Clinton.

The person or organization behind the dark-money group based in Oklahoma City is still unknown.

When hitting the theme of public safety, Valenzuela and the powerful groups backing him zeroed in on Gallego’s “no” vote on a city property tax increase in 2016. They portrayed Gallego’s vote as a decision to deny new funding needed to hire dozens of police officers and firefighters.

Back then, Gallego argued that Phoenix should look to other sources of revenue, like the Sports Facilities Fund, which uses sales taxes on rental cars and hotels for arena development, before raising property taxes. During the vote three years ago, Gallego did oppose the property-tax increase, but she supported the city budget.

In the mayoral race, Valenzuela criticized the way Gallego framed her position. “It’s very politician-y to say, ‘I support all the great things in the budget; I don’t want to support the funding behind the budget,’” he said in a debate hosted by 12 News.

The issues of taxes and arena funding converged in January, when the Phoenix City Council voted to pay $150 million up front to renovate the city-owned Talking Stick Resort Arena and approved $25 million for future repairs.

Valenzuela supported the arena deal. Among his many local corporate boosters was Phoenix Suns owner Robert Sarver, who contributed $100,000 to a firefighters’ committee supporting Valenzuela. Gallego, again, found herself on the opposite side of the issue.“Whereas someone else would think, ‘Oh, don’t even bother talking to them,’ she’ll do it." – Geoff Esposito

tweet this

“I believe that professional sports are among the most profitable enterprises out there and they should pay for their own buildings. We have real challenges in this community. We cannot afford to throw money at everything and we have to prioritize,” Gallego told New Times.

The Suns arena decision marks a setback for this philosophy, though Gallego had already resigned from the council to run for mayor before the vote took place. From her point of view, the vote to approve the Suns arena deal was rushed, Gallego explained. She believes the people who supported the deal wanted the council to move quickly after she clinched about 45 percent of the votes prior to the runoff election, the largest share of the four candidates.

Valenzuela chose to champion “safer issues” on the City Council, Gallego said, but with Phoenix’s form of government, the mayor has to “articulate a vision for the city.” From her perspective, vision means addressing the pension debt, moving to a knowledge-based economy, and supporting more early childhood education.

“I’m not gonna be the mayor who’s out there filling the potholes, but I have to talk big picture about what kind of city we become. And I think that’s where my expertise lies,” Gallego said.

With enormous problems looming on the horizon, Phoenix will need visionary solutions, and soon.

Renovations to the city-owned Talking Stick Resort Arena became a campaign issue in the mayoral race.

Gallego will lead Phoenix at a moment when the City Council is turbulent and divided. To make her job even more difficult, Phoenix faces significant challenges that have not been fully addressed.

In the coming years, climate change will render Phoenix hotter and drier. A warmer city will contribute to the heat island effect, in which rooftops, roads, bridges, concrete, and parking lots soak up heat during the day, and stubbornly refuse to let the city cool down at night. Climate change will also exacerbate water shortages on the Colorado River, which will require Phoenix to find new ways to supply water to a thirsty and growing population.

Additionally, the city continues to struggle with a budget weighed down by a $4 billion pension debt owed to public-safety and civilian employees, what is known as the city’s unfunded liability. Because of the payments owed to the state retirement system, the city budget process, which begins this spring, has grown strained. With the U.S. economy showing signs of a possible economic downturn, Phoenix could face a deeper budget crisis during Gallego’s term as mayor, along with potentially painful hiring freezes or layoffs.

Rental prices continue to rise, contributing to Phoenix’s gap in affordable housing and a Valley-wide homelessness problem.

These issues are often papered over or forgotten because of the positive things driving greater Phoenix. The city benefits from a relatively low unemployment rate and industry growth in attractive fields like health care and high-tech manufacturing. Phoenix remains one of the fastest-growing U.S. cities.

If she doesn’t vault from the mayor’s office to another elected position — “I think I’m a good fit for local government, and that’s really where I’m focused,” Gallego said when asked about her political future — she will be forced to confront Phoenix’s simmering crises.

She flinched at the oft-repeated label describing Phoenix as “the world’s least sustainable city,” the subtitle of a nonfiction book published not long before Gallego first ran for office. All the same, Gallego believes the city should prepare now for drought on the Colorado River system.

She supported a water rate increase of about $2 per month, which the council approved in January after her resignation, amid vocal dissent from the conservative wing. The new investment is meant to upgrade the city’s water infrastructure, bringing water from central and south Phoenix to the northern part of the city, a crucial step in order to prepare for looming cutbacks to Arizona’s water supply from the drought-stricken river.

While also investing in new infrastructure and fixing leaks in the system, Phoenix needs to make water conservation part of the city’s identity, Gallego suggested.

“We need to make sure that sustainable management of water is part of our Phoenix brand,” Gallego said. “If there are national headlines saying we can’t deliver water to part of Phoenix and pictures of our golf courses, that doesn’t help anyone.”

To combat rising rent prices in Phoenix, Gallego has proposed offering incentives to increase the availability of affordable housing and partnering with nonprofits to develop on city-owned land. The Phoenix City Council recently moved in a similar direction, approving a measure in February to encourage developers to offer 10 percent or more of their units at a reduced rate.

Characteristically, when Gallego worries about Phoenix, she thinks long-term. At the moment, she said, lots of people in Phoenix depend on the types of jobs that are at risk of extinction. The most common field of employment for men in her district was driving and ground transportation, like truckers and taxi drivers, she explained.

“I worry about their economic prospects in 10 years,” Gallego said. “I don’t know if those jobs will still exist, so I think we need to invest in education and diversifying the economy.”

If Gallego wants to solve these problems with visionary, forward-thinking solutions, she will need to work with her peers on the council.

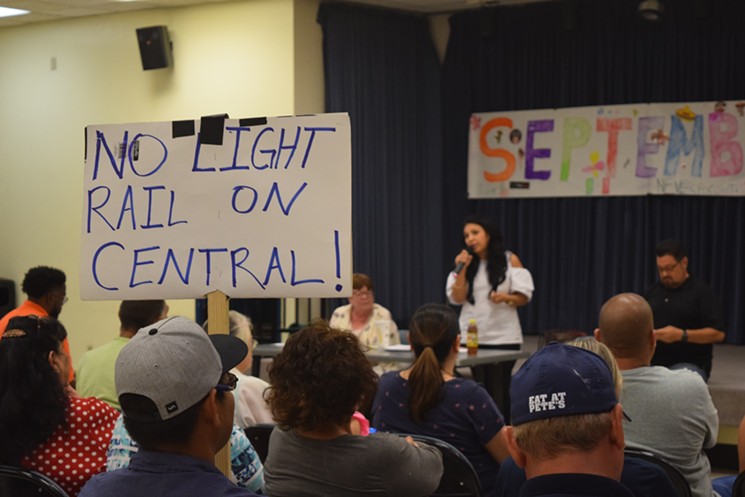

Eduardo Sanchez, 24, holds a sign at a community meeting on light rail on September 17. In the background, from left, are City Council members Debra Stark, Felicita Mendoza, and Michael Nowakowski.

Joseph Flaherty

Although the job has some executive responsibilities, the office of the Phoenix mayor is weak. In practice, the mayor is akin to an elevated member of the City Council. The mayor has one vote on the council — the same as eight other members elected from districts around the city.

Under the city code and charter, the mayor controls the policy meeting agenda. The mayor also serves as the ceremonial head of Phoenix and the chief executive officer. But because of Phoenix’s “council-manager” system of government, a city manager serves as the chief administrator of city functions and is responsible for all city employees. The council hires and fires the city manager.

Nevertheless, even under the weak-mayor system, Interim Mayor Thelda Williams noted that council members set the budget, and the city manager serves at their pleasure.

“We are not without control, and have worked always very closely with the city managers,” Williams said. “I’ve been around for almost 30 years, and every city manager listens closely [to] what our priorities are and works with staff to make sure that it’s accomplished. It might not be overnight, because sometimes we’re a little aggressive, but we always end up where we want to be.”

Stanton’s departure started a chain reaction of resignations and elections. Council members selected Williams to serve as interim mayor in the absence of a permanent leader, and ever since, the body’s work has grown more chaotic.

Gallego and Valenzuela resigned to run shortly after Stanton quit, and the council selected new members to replace them in the interim, adding more uncertainty to the council’s fragile dynamic.

Last summer, a group of Central Avenue business owners and residents along the path of a planned six-mile light rail extension spoke out against the project. Their angst about the South Central Extension’s design, which provides for one lane of car traffic, morphed into broad opposition to any light-rail expansion. Around the same time, the council deadlocked during a budget vote and nearly failed to pass the spending package. Councilman Michael Nowakowski initially voted no on the budget, citing the controversy over the South Central extension, which runs through part of his district.

In a surprise move, the Council voted to re-evaluate the design of the extension and conduct new community outreach. The decision came very close to throwing off the delicate grant process required for the city to obtain nearly $600 million in federal funds.

When asked about the apparent chaos on the Council, Williams defended her performance as interim mayor.

Working with eight people on the Council, she said, made it more difficult to approve items because they still required five votes to pass. “I think I was handed some of these challenges,” Williams said, “but I’m very proud of the fact that I took them on and successfully got them completed,” never mind that these problems will still exist under Gallego.

The City Council political contests to select permanent replacements for Gallego and Valenzuela in Districts 8 and 5 are heading to runoff elections in May.

Moreover, in Phoenix’s never-ending election cycle, two adversarial ballot initiatives scheduled for an August vote will set the course for the city’s unfunded pension liability and the expansion of light rail.

Conservative Councilman Sal DiCiccio has supported the “Responsible Budgets Act,” which would change the city charter to devote nearly all excess general fund revenue to paying down the city’s pension debt. The initiative would also end pensions for elected officials. Gallego has said she opposes the measure.

Meanwhile, the anti-light rail activists with the “Building a Better Phoenix” campaign gathered enough signatures to put an initiative on Phoenix’s August election ballot. The measure would funnel money originally earmarked for future light-rail extensions into transportation improvements.

Gallego strongly supported light-rail expansion during the mayoral race and during the 2015 referendum on the T2050 transit plan. As a result, Valley Metro CEO Scott Smith said the transit authority is excited by her victory. He said Gallego as mayor means Phoenix has “a leader at the top who is permanent and who has been a champion of transit in general.”

As the city heads toward the vote on the future of light rail, Gallego can potentially use the mayor’s office as a bully pulpit to sway public opinion, he said. If the initiative passes, it will kill the entire program of light rail expansion, not just the extension to South Phoenix, Smith said.

“It’s not just about South Central,” Smith said. “It’s trying to undo what was approved by voters in August of 2015, and Mayor-elect Gallego has sort of a personal interest in that because she was so deeply involved in the election in 2015.”

Gallego’s success as mayor will depend in part on her relationships with others on the council and whether she can muster the votes needed to pass her agenda. Opponents on the council — namely the blustering, name-calling DiCiccio — will no doubt try to stymie Gallego’s liberal priorities, but they will find it harder to do so if she has won over five solid votes, according to the former City Council staffer.

“What she’s going to have to do is build closer personal relationships with members of the council,” the former staffer said. “I’d say that is probably her biggest liability … maybe personally, she isn’t as close with some of the members of the council as she’ll need to be.”

It’s a paradoxical position to be in for a mayor who likes talking about her long-term, strategic vision. In order to silo her opponents, Gallego may have to abandon her reserved, analytical approach and become more of a backslapping politician like any other.

On past projects, Gallego has been adept at managing the interpersonal squabbling of the City Council and working with others to accomplish her goals. When she proposed that the city adopt a sexual harassment policy that would give the council the ability to remove elected officials, Gallego worked closely with Councilman Jim Waring, a Republican, in spite of disagreements on other issues.

“Whereas someone else would think, ‘Oh, don’t even bother talking to them,’ she’ll do it,” Esposito said.

Councilwoman Debra Stark endorsed Valenzuela in the mayor’s race; nonetheless, the day after the election, Stark praised Gallego for her patience and calm demeanor.

There will be tension on the Council because of the upcoming light-rail initiative, Stark predicted, but Gallego’s personality will serve her well. “I think she wants to understand the rest of the Council,” Stark said. “I do think she respects other people’s opinions, and I think that goes a long way. Not all electeds are that way nowadays.”

At Crescent Ballroom in downtown Phoenix on the night of the mayoral election, Gallego’s supporters shook off a gloomy, rainy night as they chatted and sipped drinks. A DJ fiddled with records in the corner of the stage. Other rising Democratic pols — Superintendent Kathy Hoffman, Maricopa County Recorder Adrian Fontes, Secretary of State Katie Hobbs — all showed up to the party.

A screen displayed the live results of the election from a city website, which briefly crashed. The page refreshed to reveal Gallego had a sizeable lead. The 18-month race for mayor was over.

After introductions from her campaign manager and father, Gallego walked on stage to cheers. Her son trundled around, hoisting a campaign sign above his head. She smiled. She promised the crowd, “I will work as hard as I can to be your advocate, to listen, and to push Phoenix to the next level to be a city that works for everyone.”

Any supporters holding their breath during the tumultuous last days of the campaign could breathe easier. A woman stepped onto a first row of a set of risers in the back of the room, and did a wiggling, spontaneous dance of joy.

Crescent Ballroom was an apt location for Gallego’s victory event — one of the venues in Phoenix that she and others can point to as evidence of a reinvented downtown, and the emerging sense of cool in the city’s core.

Inside the ballroom, as people posed for photos and congratulated each other, you could almost forget about the grinding issues Gallego will face as mayor: the upcoming city budget negotiation, the string of fatal police shootings, and the persistent drought that could someday scare off future developers.

If she was intimidated by the daunting challenges set before her as mayor, Gallego didn’t show it. Tonight, they would celebrate, she said. Then she would get to work.