Meanwhile, Corizon, the for-profit health care company that the Arizona Department of Corrections has contracted with since March 2013, has received millions from the state — $5.1 million over the last year alone — to treat hepatitis C. It's not clear how much of that money, if any, is spent on treating the disease.

Corizon is now in the final days of that contract, which ends June 30. The state decided in January it would not renew its contract with the company, choosing Centurion LLC as the new provider starting July 1.

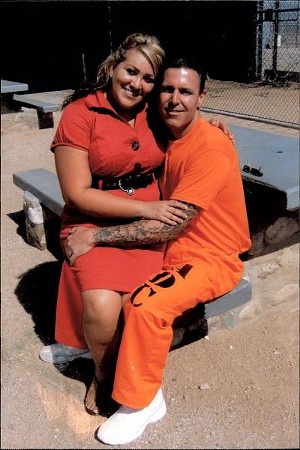

Now, with Corizon on its way out after a six-year stint riddled with allegations of medical neglect of people in state custody, Coppess is suffering from major health issues, according to his wife, Lillian, after both Corizon and the state denied his repeated requests for medical treatment.

He has filed a lawsuit against increasingly embattled ADC Director Chuck Ryan, Assistant Director Richard Pratt, Corizon, and its health administrator Benjamin Schmid, claiming that they deliberately denied him medical care in violation of his Eighth Amendment rights and showed “deliberate indifference to [his] life-threatening and serious medical needs.”

In addition to never being treated for hepatitis C, Coppess has kidney problems that Lillian Coppess says are due to his cirrhosis. Cirrhosis, scarring of the liver, can develop in people with chronic hepatitis C, and it can be fatal. Medical studies also indicate that cirrhosis, in turn, can indeed cause kidney injury.

Coppess is 46, but “you see him and he looks like a 60-year-old man,” Lillian Coppess said. “Right now, we don’t know how sick he is, at what stage his cirrhosis is,” she added, but she feared it has reached advanced stages after years of neglect in the state's prison system. He is now nearly halfway through a 35-year sentence for aggravated assault and murder.

Her husband might need a liver transplant, but there's no way of knowing without the appropriate medical tests. Coppess is also awaiting the results of a cystoscopy, a test for bladder cancer done in mid-June, two days after Phoenix New Times first asked Corizon about Coppess.

For months, he has been unable to urinate without a catheter, and medical records show that Coppess has suffered multiple urinary tract infections. Chronic urinary infections, which can result from long-term catheter use, are a risk factor for certain bladder cancers.

In March 2018, Coppess filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court. He demanded a jury trial and asked for $7 million in damages, plus a “permanent Injunction to order Defendants to provide [hepatitis C] treatment.” Although the defendants asked in January for U.S. District Judge James Soto to dismiss the case, the case remains in federal court; additional exhibits were filed as recently as April. In February, the judge denied Coppess' request for a lawyer.

As the lawsuit noted, medical standards that are supposedly followed by Corizon and the state make patients with “known or suspected cirrhosis” a top priority for treatment. The state and Corizon included, as evidence, federal clinical guidance from January 2018 stating the same. But records included as exhibits in Coppess’ ongoing lawsuit show that Corizon decided he didn’t qualify for hepatitis C treatment.

Coppess was diagnosed with cirrhosis during a hospital visit in 2013, a few months before Corizon’s contract began, medical records shared by Lillian Coppess show — records she received from Corizon.

Somehow, Corizon never followed up on that diagnosis, even though it had a clear record of it. Nor did it incorporate the diagnosis into Coppess' electronic medical record, health records submitted as exhibits in the lawsuit show.

“In this case, evidence has been presented that the defendant not only failed to monitor and/or treat the plaintiff’s [hepatitis C] but by unwritten policy, practice, and long-term custom consciously refuse to either regularly examine, monitor, or treat any ADC prisoners,” Coppess wrote in one court filing. He added that he feared he would pay the ultimate price as a result.

In their response to Coppess' complaint, Corizon and the ADC denied “the existence of any policy, custom, or practice amounting to deliberate indifference.”

'Nothing is being done to help me'

Coppess was diagnosed with hepatitis C in 2009, when a different company, Wexford, was the health care provider for the Arizona state prison system. The following year, he signed a release consenting to be treated for the disease, according to his complaint and medical records.But Wexford then accomplished as much as its successor later would: It never treated Coppess' hepatitis C, according to Lillian. A long list of medical grievances at ADC facilities includes an affirmed complaint from an inmate at Santa Rita in December 2012 about Wexford’s failure to treat hepatitis C. Identifying information is redacted, so it's not clear if the person is Coppess or another person deprived of care for hepatitis C.

In August 2011, a biopsy indicated that Coppess had chronic hepatitis C, but not cirrhosis — yet. That would take another year or so.

In January 2013, Coppess was assaulted. His spleen ruptured, and he was taken to Banner University Medical Center, records provided by Lillian show. In the process of doing a CT scan and removing Coppess’ spleen, doctors also diagnosed him with cirrhosis. He was 40 years old at the time.

The cirrhosis diagnosis went into Coppess’ file with Corizon, but apparently had no sway over its decision regarding treatment for hepatitis C.

In December 2017, when Coppess submitted a medical request for hepatitis C treatment, he also sent letters to ADC Director Chuck Ryan and Assistant Director Richard Pratt, pleading for help.

“Being that you're the Director of ADC I know you have the authority to authorize my Hep C treatment. I was diagnosed with Stage 2 cirrhosis in 2011 [sic], and am positive it has gotten worse since then," he wrote to Ryan. In his letter to Pratt, he begged for help. "Nothing is being done to help me. Will you please get me the treatment I need," he asked.

Coppess also filed an informal complaint resolution and a formal inmate grievance asking for treatment.

In a response dated January 23, 2018, a nurse from Corizon wrote back, “Your concern has been reviewed by medical and it was determined that on 1/17/18 you saw the medical provider who went over your current health status extensively. At this time you do not meet the necessary criteria to qualify for HEP C treatment while in ADOC.”

She added, “This has resolved your concern.”

In its legal statement of facts, ADC and Corizon said that Coppess’ bloodwork did not indicate a need for hepatitis C treatment. His liver enzyme levels were inconsistent — sometimes they were high, other times they were normal — according to medical records they submitted. They pointed out that Coppess had shared needles in the late 1980s and gotten his first prison tattoo in the late 1990s. In other court filings, they argued that Coppess’ injuries were “due to his own negligence or recklessness.”

Corizon had monitored Coppess' enzyme levels, they added, and based on federal guidelines that ADC and Corizon followed, “it is not medically appropriate to prioritize [Coppess] for ... treatment.” Despite having provided Coppess' wife with a medical record indicating a diagnosis of cirrhosis, they claimed that hepatitis C was noted in Coppess’ electronic medical record but cirrhosis was not.

They added, though, that “assessing for cirrhosis is important in prioritizing inmates for [chronic hepatitis C] treatment.”

In addition to highlighting his cirrhosis, Coppess argued in his complaint that those blood tests likely did not accurately reflect his medical conditions, because he’d had his spleen removed five years earlier.

“The fact that [Coppess] suffered a splenectomy in 2013, may invalidate the blood tests performed by Corizon,” he wrote, adding that those blood tests were “preliminary/cursory.”

Although nurses had submitted requests for more advanced testing, including a liver biopsy and a CT scan or ultrasound, Corizon’s administrators denied those requests, he added.

In response to emailed questions from New Times on the morning of June 11, Corizon spokesperson Eve Hutcherson said that the company couldn’t discuss individual cases.

“I am happy to research your questions regarding general process, but ... you have not provided us enough time in order to do that,” she added in an email that morning.

“Unless you are willing to extend your time frame, please feel free to include that you contacted us just prior to deadline (intentionally, I assume) and did not provide us sufficient time to answer. You will not be the first journalist in Arizona who did not care enough about the actual facts to allow us sufficient time to provide them,” Hutcherson wrote.

New Times agreed to give Hutcherson two more days to research those questions, which included queries about how Corizon notified patients diagnosed with hepatitis C or cirrhosis and its treatment for those diseases.

On June 13, Hutcherson sent a brief response: “Corizon’s clinical team diagnoses and treats patients as indicated, and we notify patients of their diagnosis as soon as possible.”

The same day, Lillian Coppess said her husband was taken on the two-hour drive from Arizona State Prison Complex — Tucson to a hospital in Maricopa County, where he received testing for bladder cancer. That appointment was about three months overdue, she said.

On two previous scheduled trips to the hospital, Coppess was transported too late, and he missed his appointment each time. The last time the prison actually managed to get Coppess to a hospital on time, she told New Times, was shortly after a visit from an ACLU attorney.

This time, the urologists told her husband “they were very upset,” Lillian relayed. He should have been seen two or three months ago, they said, and they suspected that his struggles to urinate were due not to a blockage but to bladder cancer. They believed he needed surgery, and soon, she said."I have been trying to get treated since before 2011, when I was diagnosed with Stage 2 cirrhosis. I’m sure it has gotten worse since then, but nothing is being done to help me." — Wellington Coppess

tweet this

Anthony Fernandez and Ellen Burno, lawyers with the firm Quintairos, Prieto, Wood & Boyer who are representing Ryan, Corizon, and the other defendants, did not respond to an email and a voice message seeking comment. An ADC spokesperson did not respond to two requests for comment.

A new contractor

In recent years, the Arizona prison system and its latest contractor, Corizon, have become all but synonymous with medical neglect. Five years ago, ADC settled with the American Civil Liberties Union in the federal case Parsons v. Ryan and was required to improve medical facilities in its prisons. Last June, following reports from local NPR affiliate KJZZ, a federal judge ruled that the state had failed to meet those requirements and imposed a fine of $1.5 million, but the stories of egregious medical neglect continue to emerge.

In January, an inmate named Richard Washington died of complications related to diabetes, hypertension, and Hepatitis C. “I am being killed,” he wrote in a court filing six weeks before his death, adding that the state was "actively refusing" to give him medication, New Times reported in February.

This year, repeated requests from James Leonard to see a medical provider about serious urinary symptoms went ignored until New Times began asking questions about him. The doctor told him he wouldn’t have been seen without outsiders lobbying on his behalf. Even so, the treatment that Leonard received was grossly inadequate and a recipe for infection — two thin rubber tubes for a catheter, no bag, and no cleaner.

Leonard and Coppess are still incarcerated, but within a few days, Corizon will be extricating itself from Arizona's prison system. In its January press release announcing that Centurion would become the new provider, ADC promised the handover would be seamless.

“ADC’s current inmate healthcare provider, Corizon, will continue to perform its existing contractual obligations, and is expected to work with ADC, and Centurion, to ensure a smooth transition of existing services,” it said.

As Centurion moves in to Arizona, it will be on its way out in neighboring New Mexico, where it has faced allegations of medical malpractice and negligence, among other grievances. New Mexico's corrections department is seeking a new health care provider to replace Centurion in November.