The 34-year-old had lived in the United States since he was a baby, when his family moved to Phoenix, Arizona, from the border town of Nogales, Mexico. He grew up here and raised his family here. He was a legal permanent resident with a green card. And he chose to serve his country, enlisting in the U.S. Navy and deploying to the Middle East as an aircraft mechanic.

When he enlisted, military recruiters promised him citizenship, he said. He was so sure he could trust them, he told his parents not to bother when they tried including him in their own citizenship applications. “No, mama,” his mom, Leticia Murillo, remembers him saying. “You don’t need to do it. The Navy’s going to help me.”

So, when Murillo’s 2009 arrest for transporting marijuana across state lines led to immigration court proceedings, he was confused. He raised his hand at every hearing when the judge asked if anyone thought they were a U.S. national, citizen, or veteran and didn’t belong there.

And when those hearings led to him sitting on a bus in his gray prison sweatsuit, southbound toward Mexico in 2011, he still hoped it was all a mistake.

“Why are you sending me here?” Murillo remembers thinking. “I’m not even from here. It’s my origins, that’s where my family’s from, but me? No, homie. I’m an American.”

Murillo waited for the bus driver to pull over. He imagined somebody would come aboard the bus full of prisoners, point at him, and say, “Not this guy right here. Everybody, but not this guy.” They’d unshackle him, apologize for his trouble, and let him go home to his four kids in Arizona.

But when the bus eventually did stop, and his shackles were removed, Murillo’s first steps of freedom were his last steps in America. Officials ushered him toward a chain-link border fence in the dark. They handed him a package of shrimp-flavored cup noodles, gave him one phone call, and sent him on his way.

He planted his right foot in the United States, stepped through the gate with his left, and walked out into a country he didn’t recognize.

From Service to Exile

Over the years, America has deported busloads of military veterans like Murillo, exiling them outside of the nation they once risked their lives to protect.The U.S. military has depended on immigrant soldiers in every major conflict since the Revolutionary War, and still allows applicants with permanent residency status — so-called green card soldiers — to enlist. Some 44,000 noncitizens joined the military between 2013 and 2018, according to Department of Defense data. But even though they fought for their country, those service members can lose their right to live in the United States if they commit a crime deemed an “aggravated felony.”

That term originally referred only to serious crimes such as murder and gun trafficking, but its definition has expanded over the years to include less serious charges, such as drug crimes, theft, falsifying documents, and tax fraud.

Some say deported veterans deserve their fate. If they didn’t break the law, they wouldn’t face removal. But a growing number of supporters see them as victims of an unjust system. Many veterans say they were promised automatic citizenship through their service, but were never granted it. Deported veterans say they have been punished twice for their crimes and pushed aside, often to countries where they haven’t lived since childhood, don’t speak the local language, and face obstacles that inhibit access to the benefits they badly need. In some cases, a lack of resources from Veterans Affairs to treat their service-related injuries or mental illnesses is part of what led them to commit a crime in the first place.

At best, these displaced veterans can find work in the countries where they’ve landed.Ironically, veterans ousted from the country are still entitled to a military funeral on U.S. soil.

tweet this

At worst, they’re targeted by gangs and cartels who recruit them for their military skills, threaten their families, or — in the publicized case of at least one veteran — kill them.

Those who remain in exile have cause to be cynical about how they’ll ultimately be honored for their service: If they can’t make it home to the United States while living, they can do it after they’re dead. Ironically, veterans ousted from the country are still entitled to a military funeral on U.S. soil.

There is potential for change. Some politicians have tried to introduce legislation to help deported veterans obtain citizenship, but so far, such efforts have languished in Congress. And while governors in California and Illinois have pardoned a select few deported veterans, most elected leaders — including Arizona’s Governor Doug Ducey — have opted not to engage.

For deported veterans still hoping for a pathway back to the United States, all they can do is wait.

The Kid from Phoenix

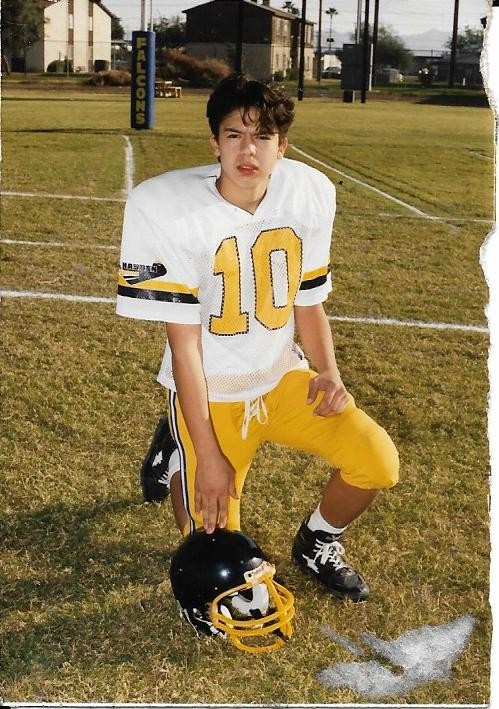

When Alex Murillo was a kid growing up in west Phoenix, he spent his afternoons playing sports at Encanto, Oso, and Falcon parks. He loved the ribs at Bobby McGee’s barbecue off the freeway, and the enchilada-style burrito at the mom-and-pop joint La Canasta. He was a quiet child, according to his mom, but he let it all out on the basketball court. When his team at Isaac Junior High won the state championship, he earned MVP.

Now, he can only see Phoenix through a computer screen. It’s been almost eight years since his deportation. The 42-year-old Murillo lives in the coastal town of Rosarito, Mexico, 16 miles south of Tijuana in the state of Baja California. On afternoons when he’s not working at a call center or coaching high school flag football, he sits in his living room and uses Facebook to video chat with friends and loved ones, an Arizona Cardinals helmet visible in the background.

Murillo is an infectious optimist, the kind of guy who types smiley faces and thumbs-up stickers into every message. He talks to a reporter like he’s talking to a friend, filling conversation with slang like “man” and “dude.” But even through a video screen, his eyes appear tired and his cheeks hollowed from stress, which has mounted ever since he joined the Navy at 18.

Murillo enlisted in the military just after graduating from Carl Hayden High School in 1996, when he got his girlfriend pregnant. He had college basketball dreams, but he wanted to support his new family, be an adult, and serve his country. His mom begged him to stay, telling him she would help out with the baby. “No, mama,” he told her. “I need to take care of this myself.” He became an aircraft mechanic on the USS George Washington.

Out at sea on an aircraft carrier three football fields long, Murillo felt the most pride and the most heartache he’d ever felt in his life. He was proud to serve his country and loved the “brothers” he made there. They went through “crazy shit together,” he said, never knowing what would happen next. He spent long days topping up oil and patching panels on S-3 Viking anti-submarine warplanes, and spent nights bonding with his fellow airmen, who knew him as “the kid from Phoenix.” But he was still a teenager, wrestling with fatherhood and sacrifice. Standing out on the flight deck day after day, seeing nothing but ocean, he felt small and far away from everything and everyone.

The stress of his tour and problems in his relationship eventually led Murillo into a depression. He self-medicated with marijuana and alcohol, in a period he now describes as a “mental breakdown.” He said he attempted suicide at that time — he declined to go into detail about it. In 1999, after he spent time with military doctors and psychologists, the Navy released him with an other-than-honorable discharge.

Transitioning to civilian life wasn’t any easier for Murillo, who had become addicted to alcohol and developed post-traumatic stress disorder from serving in the military. He and his wife had two more children, but their relationship was rocky and eventually crumbled. Murillo worked all kinds of jobs in Phoenix to afford child support for three kids. One of his favorites was installing DISH satellite TV in people’s homes across the Valley. But he was overworked, and broke, and he didn’t get to see his children much. So in 2009, he took a job he thought would cover the expenses for a while and allow him to spend time with his family. He drove 850 pounds of marijuana across the country for the promise of $10,000. He got busted at a truck stop in St. Louis.

At his sentencing, according to local reports at the time, Murillo told the judge he was ready to turn his life around. “This is the lowest point,” he said. “I don’t want to go lower than this.”He was thrown into solitary confinement, stripped of his drug-treatment privileges, and placed into a medium-security prison that was never part of his sentencing.

tweet this

What he didn’t know then was that the 37-month sentence the judge would give him at a federal prison in Lompoc, California, would be the last months he would spend in the United States. Three months into his stay at a prison camp with no walls and no fences — “I could have walked away whenever I wanted to, but I didn’t,” Murillo said — U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents tracked him down. He was thrown into solitary confinement, stripped of his drug-treatment privileges, and placed into a medium-security prison that was never part of his sentencing. That’s when his deportation proceedings began.

Murillo finished his sentence early, in December 2011, but that didn’t mean he was free. Instead, he boarded a prison bus that took him straight to Mexico.

From there, he would soon see his children’s lives unravel, unable to be there for them because of a border and the policies that trap him on one side of it.

Policy vs. Reality

Here’s how the life of a noncitizen who serves in the military is supposed to go, according to the U.S. government: After serving honorably in the military for a year during peacetime or any stretch during wartime, green card soldiers can apply for citizenship with expedited processing.Simple, right?

But advocates for deported veterans say this isn’t what’s happening in practice.

Sometimes, a veterans’ service isn’t deemed honorable after they experience mental health issues or a single bout of bad behavior during their service, potentially disqualifying them from expedited naturalization.

Other times, noncitizen veterans plan to apply for citizenship, but struggle with the transition out of active duty and are convicted of a crime before the application can be finalized. Murillo didn’t even get to that stage — he didn’t realize he needed to apply because he thought the military would help him.Even when they do apply for citizenship, many veterans are denied it.

tweet this

Even when they do apply for citizenship, many veterans are denied it. Other times, the background checks and bureaucratic requirements cause so many delays that the veterans are left in limbo. The Trump administration heightened these requirements in 2017. Partly as a result, in the last few months of 2018, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services data showed that 16.6 percent of veteran citizenship applications were denied, a 5 percent higher denial rate than for civilian applicants. The number of naturalization applications also dropped sharply.

All of this threatens green card veterans, advocates say, because veterans as a group face proportionately more risk factors for criminal activity than the general population. When those risk factors lead to brushes with the law, green card veterans have more than just their criminal records at stake.

Carlos Luna, president of the Chicago-based advocacy group Green Card Veterans, said in a recent interview with Phoenix New Times that veterans’ programs don’t adequately treat service-related medical and mental health issues, leaving noncitizen veterans vulnerable to making mistakes that could get them deported.

“Let’s take an average enlistment,” he said. “Four years. That person has been wound up for four years. And they’re released into an environment that does not have any processes or procedures to wind down. What do

you think is going to happen? Especially when you add in the co-occurring conditions of substance abuse, of depression, of anxiety.”"That person has been wound up for four years. And they’re released into an environment that does not have any processes or procedures to wind down. What do you think is going to happen?"

tweet this

ICE is supposed to place special consideration on veteran status — weighing things like the veteran’s health, service history, criminal record and family and financial ties to the United States — during deportation proceedings, but doesn’t always do that, according to a June report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office. The report found that 70 percent of cases involving noncitizen veterans didn’t get the mandatory level of review.

In response, Yasmeen Pitts-O’Keefe, a spokesperson for ICE, said the agency is “very deliberate in its review of cases involving veterans,” and “identifies service in the U.S. military as a positive factor” to be considered among all factors.

She also said, though, that the law “requires ICE to mandatorily detain and process for removal individuals who have been convicted of aggravated felonies.”

A Network for Change

After green card veterans get deported, new problems arise. Chief among them is that while they are still entitled to all the same financial and health benefits they received at home, the system isn’t built to make those benefits accessible in another country.

Few know this better than Gil Vergara Calderón, a Phoenix resident and disabled army veteran who volunteers his free hours helping his fellow servicemen navigate the convoluted system of obtaining their benefits while

stuck abroad.

Vergara Calderón said that a lot of the veterans he’s spoken to in Mexico don’t know how to fill out the necessary documents online. Because these veterans are out of the country, there aren’t Veterans Affairs offices near them that can help.

Plus, since medical exams are necessary for some benefits, arrangements have to be made to get doctors sent to veterans who need them.

Some don’t even know they’re entitled to benefits as deported felons, until Vergara Calderón or someone else reaches them and explains.

“I haven’t seen you this happy in a while, brother,” Vergara Calderón told a veteran in Mexico over Skype on a recent weekday morning at Starbucks, where he often spends a few hours on veteran paperwork before going to his own full-time social-work job. Vergara Calderón had just managed to help the veteran get his disability pay in Mexico, a life-changing development for the man, who was an English teacher on a Mexican salary.

“If something happens, man, you know what to do,” Vergara Calderón said. “Just hit me up.”

Vergara Calderón coordinates with the Deported Veterans Support House, or the “bunker,” a refuge for displaced veterans in Tijuana who might otherwise fall homeless or draw threats from gangs on the streets.

The bunker and a different organization, Unified U.S. Deported Veterans, have brought together dozens of deported veterans in Mexico for advocacy, safety, and camaraderie in a country that can be dangerous for U.S. military veterans.

Dog tags of deported veterans who died abroad hang at the "bunker" in Juarez, Mexico.

Gil Vergara Calderón

On October 29, Hector Barajas, founder of the Deported Veterans Support House, testified about the problem to

the House Judiciary Committee. Barajas was able to return home after being pardoned by California’s former Governor Jerry Brown. He is one of a handful of veterans who have returned home this way.

Vergara Calderón organized a protest on the steps of Arizona’s capitol last year in an unsuccessful attempt to speak to Governor Ducey about the issue. Ducey, in spite of being a vocal supporter of veterans, didn’t respond to requests for comment for this story.

It can be taxing, Vergara Calderón says, but he still spends around two or three hours a day devoted to the issue.

“It takes definitely quite a lot of time,” Vergara Calderón said, “but I love doing it. They’re not forgotten. But a lot of these folks, they feel like that.”

‘They’re Good Kids. But They Needed Their Dad.’

Murillo's mother, Leticia Murillo, drove around Phoenix looking for her grandkids until she found them.

Ali Swenson

Of all the suffering Murillo has endured since he was deported, from being paid $175 a week to support himself and four children, to still not being able to access the VA benefits he needs for his PTSD, nothing compares to hearing over the phone that his young adult sons were sleeping in cars and abandoned houses in Arizona, addicted to fentanyl and putting their lives in danger.

It was around February 2019 when Murillo got a call from his kids’ cousin, who had seen Murillo’s eldest son Junior on the streets in Phoenix.

“He said they had no food,” Murillo recalled during a video call, his eyes welling with tears. “He was staying in cars and at the hospital and at the park. Their shoes were all tore up. I could do nothing. I couldn’t help them. I wouldn’t wish that on any parent.”

In the years since his deportation, Murillo had tried to create a stable life in Rosarito, Mexico, re-learning Spanish and getting two jobs to support his kids on a Mexican salary. He would wake up at 3:30 a.m., work out, work a full day at a call center, and then coach flag football for a local high school.

But at the same time, his kids, Junior, Angel, Anita, and Athena, a half-sibling to the other three, were all growing up in Phoenix without him. The older kids’ mom, Murillo said, was using drugs and not always around.

That left the kids without a stable parental figure. Murillo’s oldest kids, his sons Junior and Angel, began using opioids and disappearing for days or weeks at a time.

Leticia Murillo was living in Phoenix, too, and could see her grandkids struggling. At first, she would take the kids out for meals and clothes-shopping, trying to provide them stability.

“They’re good kids,” she said. “But they needed their dad.”

But eventually, in the throes of fentanyl addiction, her grandsons stopped answering her calls. She would drive aimlessly at night, looking for them on the streets of downtown Phoenix. They were missing for about a year and a half.

“I couldn’t sleep at night thinking if they were still alive,” she said.

Murillo, hundreds of miles away across the border, felt powerless. He frantically called his mom for updates. He had learned growing up that if you’re ever in trouble, you can call your elected official, so he started making calls to Congress.

Raul Grijalva, Kyrsten Sinema, Ruben Gallego. He called them on a loop, two, three, four, five calls every day. He also called representatives from other states, to help other veterans get home.

He posted the videos on Facebook, numbering them as he went, always with some sort of message: “My family still needs me home, I’m still making the calls. Help my family be reunited.”

He had a few encouraging conversations with elected officials. Representative Raul Grijalva called him back on his cellphone once, telling him, “I’m with you, brother.” But nobody ever helped him find his kids.

Murillo's sons, Junior, 22, and Angel, 20, are healthier now that they live in Mexico with their dad.

Alex Murillo

Leticia Murillo helped her grandsons into detox programs, and at their father’s request, sent them to Mexico in April so he could nurse them back to health. Now, three of Murillo’s four kids live with him in Rosarito. His youngest daughter, Athena, 13, stayed in Phoenix with her mother.

Murillo’s kids help him coach flag football at the local high school, and he helps them produce rap music. They cull beats and inspiration from their favorite Prince, J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar tracks in the living room, where he still makes calls to members of Congress whenever he can.

“I’m as happy as can be. With my kids here,” Murillo said. “But I still know that I deserve to be home with them.”