In our sprawling, ever-expanding metropolis, these spiders, which are notorious for their venomous bites and unforgiving mating methods (females sometimes kill and eat males, post-coitus), are thriving.

Phoenix is the country’s second fastest-growing city. As we settle here, hardening our urban jungle with more roads and concrete sidewalks and walls, we often tend to displace the wildlife — the rattlesnakes and jackrabbits, the native willows and cottonwood — that we find to be in our way.

Not black widows, though.

Black widows are one of two types of venomous spiders in Arizona, the other being the brown recluse. Only the females, which bear the species' hallmark orange or red hourglass on their bulging, round abdomens, bite, and only if they feel threatened. They inject their victims with a tiny dose of a powerful neurotoxin that can cause muscle aches, vomiting, high blood pressure, and difficulty breathing.

For some, usually children, the elderly, or the ill, these bites can be fatal — although such deaths are extremely rare. Of 1,866 black widow bites reported to the American Association of Poison Control Centers in 2013, 14 were severe, and zero were fatal. Still, the black widow's reputation precedes her.

Figuring out why and how these legendary arachnids have taken so well to their urban environs is the work of biologist and associate professor Chad Johnson and his students at the Arizona State University's West campus. Ever since Johnson started a spider lab 12 years ago, he and ASU students have been trying to tackle the tough questions by breaking them down into smaller, more answerable ones, like why city spiders are bigger than their desert counterparts, or how the warmth of an urban heat island like Phoenix affects them.

Their research offers glimpses into the impact of a warming planet and expanding human footprint on ecosystems within cities.

“We’re losing species diversity because of climate change,” Johnson told Phoenix New Times in a recent interview. “What we’ve been trying to do with the lab is take the opposite angle and ask what’s going on with the animals that are thriving with increased carbon dioxide, with increased human disturbance.”

Some of the chief findings from Johnson’s lab in years past are that western black widows — a.k.a. Latrodectus hesperus — in the city are bigger than those in the desert, that their urban populations are denser, and that prey is more abundant in the city.

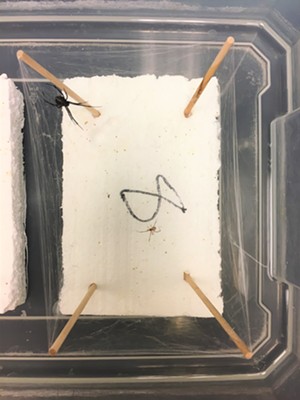

The female black widow (top left) sometimes eats the male (center, just below the "8") after mating.

Elizabeth Whitman/Phoenix New Times

He estimated that populations of urban spiders are 10 to 15 times denser than in the desert. “When we go out in the desert we could spend four hours and come home with three spiders,” he said. With that much time in the city, he said, “I could get 5,000 spiders.”

“The numbers are just creepy, if you think about it — how abundant they are,” Johnson added.

A group of scientists with whom Johnson collaborated, led by Lindsay Miles at Virginia Commonwealth University, also found recently that the genetics of urban spiders are much different from the genetics of desert ones. To Johnson, this suggests that Phoenix’s urban black widows didn’t originate in the Sonoran Desert but were transported from elsewhere by humans. “That’s the only way those genes could get to be so different in the city,” he said.

He has a few other ideas that have less to do with DNA about why black widows do so well in cities: more food, fewer predators, and top-notch infrastructure for spider homes.

“In the city, there are very few enemies,” Johnson said. Natural predators like parasitic wasps, which eat spider eggs, don’t tolerate cities well, for example. “There’s somebody with a Raid can, but they’re not very good predators.”

City spiders also have more to drink and eat, thanks to humans, especially those who like their landscaping and who take care of their lawns, plants, and gardens. This practice invites more animals that eat plants, including ants, geckos, and especially the Indian house cricket, Gryllodes sigillatus, the invasive species that “black widows are living on,” said Johnson.

Our urban jungle also gives black widow spiders ideal places to weave webs. Western black widow spiders like to build large, full cobwebs, the kind that a person’s fingers might catch in if they drift to the underside corner of a bench. Besides catching food in these webs, they spin sacs filled with eggs — anywhere from 300 to 400 when they live in the field, and up to 800 in the lab.

“In the desert, there aren’t just miles of concrete block wells that are tailor-made to anchor a three-dimensional web,” Johnson said. “A cactus can do that, but not as reliably as just a city full of concrete walls.”

Most recently, Johnson’s lab has been studying the effects of heat on these spiders by raising groups of spiderlings in two different temperatures — 27 degrees Celsius (80.6 degrees Fahrenheit) to mimic the desert, and 33 degrees Celsius (91.4 degrees Fahrenheit) to emulate the city — and parsing the subsequent differences in their bodies and behaviors.

But not everything they’ve found is intuitive, raising questions about the seeming paradox of black widows’ thriving in Phoenix, even as scientific research suggests that the heat of the city actually makes growth and development more difficult for these spiders.

Johnson’s lab at ASU has a funky scent, brushed with the mustiness of mild decay. “Crickets,” Johnson said. (Spider food.) “Crickets stink.”

Johnson opened the door to an incubator, which resembled a large refrigerator. It was filled with trays upon Styrofoam trays of spiders in cubes of clear plastic. He pulled one out.

The spider clung to the underside of the lid. She was a teenager, having molted about five or six times so far in her life. In another week or two, she’d be an adult. Her enormous abdomen was black, her legs a dark, deep brown. At the bottom of the cube, atop a bed of puffy white gauze, lay dried and crumbled bits of bug.

“Just the remnants of a cricket carcass that she’s wrapped up, and pulverized, and sucked dry,” Johnson said casually. Two tables away, a graduate student tapped away at his laptop.

Johnson’s lab workers collect spiders, typically females, from the city and the desert. In the lab, the females will make egg sacs. From there, the students divide the sacs or hatched spiders into different environments, putting groups of siblings into both categories in order to account for differences in spider families. They collect data and compare the different populations to answer questions: How fast are they growing? How cannibalistic are they? How aggressive? How are they building webs?

This work is done in the lab, rather than in the field, because they are able to collect more and better data, Johnson said. One year, they tried to study 20 urban spiders in their native webs, outside the lab.

“The webs all got destroyed, because people at bus stops see you there, and go over there, and they ruin your data,” Johnson said. Field work is also time-consuming and difficult, he added, and since he teaches during the day, going out at night to do field research is “not something my family — that I — want to tolerate,” he added.

Two tables away, graduate student Ryan Clark was tapping away on his laptop.

Heat dramatically changes the bodies and behavior of black widow spiders.

Elizabeth Whitman/Phoenix New Times

Indeed, Clark told New Times that over the summer, he had done experiments with the spiders in an outdoor enclosure in a parking lot, and he had the pictures to prove it.

All of this work is done on a spider-string budget. Johnson receives $500 a semester to mentor undergraduate students, and he’s still using the $45,000 he received in ASU startup funds, even though he’s been at the university for 12 years. “I make that last,” he said.

The lab’s latest research has produced some unexpected results — namely that the development of baby black widow spiders slows dramatically in the heat. The spiders raised in the warmer temperatures were underweight, compared to their chilled-out brethren, and they were more prone to cannibalizing their fellow spiderlings. Other than the different temperatures, they were raised in the same environments, with the same amount of food.

A possible explanation has to do with the hormone ecdysone, which prepares arthropods like spiders, insects, and crustaceans to molt. In the heat, spiders get spikes of ecdysone, Johnson's lab has found. Those rushes, called toxic ecdysonism, can lead to problems like increased metabolism or premature molting, Johnson explained. His working hypothesis is that these hormonal bursts are the mechanism behind spiders' slowed development in the heat.

This latest research is not yet published, but Johnson expects the results to hit scientific journals early in 2019.

If living in warmer temperatures doesn’t speed up spiders’ growth, but urban spiders tend to be bigger, Johnson wondered if the difference in spider size was due to food. And so that is one of the experiments Johnson's lab is conducting now. They're putting the spiders in warmer environments again, but this time, they're also giving them more food, a situation that Johnson said better simulated the real-world city.

“What we don’t know yet is if heat and added food could turn them into the problem that they are,” he said.

They are also currently trying to study whether city spiders are less cannibalistic than their desert counterparts, or vice versa. It's possible that black widows are thriving in Phoenix because they've learned to get along with each other a little better.

If true, that would bode well for the urban black widows settling in the Valley of the Sun, but perhaps less so for the humans.