Walk around Garcia and you see basketball hoops, a cafeteria, and classroom pets like frogs and betta fish — the component parts of any school. But you can’t see the feature that defines the school even more than its mascot and the trucks aggressively downshifting on Buckeye Road.

The impact of school segregation in Phoenix is invisible and all around you at the same time, like a suffocating heat rising off the asphalt.

The public K-12 education system in Phoenix is complicated — fractured into over two dozen public school districts, specialized magnet programs, and independent charter schools, all governed by open-enrollment rules. But strip away all the labels and, in reality, Phoenix has just two types of schools.

One group of extremely segregated, underperforming schools educates black and Latino kids. Nearly two-thirds of public school students of color in Phoenix attend an extremely segregated school, where 90 percent of students or more are nonwhite.

The other group serves the rest of Phoenix.

To see that segment of the Phoenix school system at work, drive a few miles northeast of Garcia — past the grim industrial zones with fences topped by razor wire, over the Southern Pacific railroad tracks, through the shadow of Chase Field, and along two roaring freeways. Inside of what looks like a drab downtown office is BASIS Phoenix Central Primary, an academically rigorous charter school celebrated by Arizona politicians and school-choice proponents.

“Hurry up ladies, you’re going to be late!” Rosalind Thompson, the head of BASIS Phoenix Central, reminded a pair of students walking idly past the lockers on a recent Monday morning.

In the kindergarten classroom, kids waved their hands in the air, waiting for a turn to name insects like dragonflies and ladybugs. One instructor was sitting at a desk by the door while another teacher stood by a projector screen at the front of the room, fielding answers about bugs.

“We have two teachers in the class, so either one can teach,” Thompson explained in a whisper — a luxury unheard of in Garcia’s school district, which has shed teachers recently.

Last year, U.S. News & World Report placed five Arizona BASIS schools in the top 10 best high schools in the country. From first to fourth grade at BASIS schools, students move from classroom to classroom, learning from teachers who specialize in the subject, unlike other schools where a single instructor teaches everything.

At Garcia Elementary, the passing rates for state standardized tests are abysmal. The school earned a D rating under Arizona’s A-F letter grade system.

When Teresa Tejeda attended Garcia, the school looked different. Back then, dirt roads surrounded her south Phoenix home. Now, the streets are paved. When she was a student, teachers emphasized rote pencil-and-paper exercises, unlike the interactive lessons of today, she recalled. Some of Garcia’s classrooms were located in the basement. Now, there’s a long line of classrooms where the metal doors each have a number and open to the air.

Other things haven’t changed in the years since Tejeda graduated. She is now a 49-year-old first-grade teacher, and Garcia is still overwhelmingly made up of students of color in 2018 — just as it was in 2008, 1988, and 1968.

On a Wednesday morning in March, Garcia students piled their backpacks on the grass while they ran around on a basketball court where nearly all the netting was stripped away from the hoops. Inside her windowless classroom, Tejeda marked down attendance as students grabbed cartons of milk and apples out of a cooler.

“All right, get your breakfast, let’s go!” Tejeda said. A YouTube video about counting to 20 played over the projector system.

It was dress-like-the-flag day, so Tejeda’s students, who are all English-language learners, were in shades of red, white, and blue. Community volunteers were scheduled to read a Dr. Seuss book, but they never showed up, so Tejeda did the activity herself.

“Now, an illustrator is the one who draws the …” she said.

“Piiiiiictures,” the kids replied in unison.

“What do you notice about the words, Sergio?” Tejeda asked. “Stop, drop, top.”

“That they are all verbs?” he said.

“They’re verbs?” Tejeda laughed — he was right, but it wasn’t the answer she was looking for. “They rhyme! Stop, top.”

Ninety-three percent of students at Garcia are Hispanic and 90 percent are eligible for free lunch, according to last year’s enrollment numbers. The district’s finances are in a state of free fall, and in February the district governing board considered cutting teacher salaries by 5 percent in order to make it through the school year, before they backed down in the face of teacher protest.

For Tejeda, a single parent who has taught in the Murphy Elementary District for 13 years, the year has been fueled by anxiety. “This is our life, you know? Our lives are in their hands,” she said after the district voted down the pay cuts.

Tejeda has considered leaving, but she feels like she owes it to her students to stay. Because she has always taught in the Murphy district, she has no idea what the experience is like on the other side of Phoenix’s divided school system.

“I always wonder, ‘Well, is it greener on the other side? Is it the same? Is it better?’” Tejeda said later from her classroom. “You never know. I don’t know, because this is all I’ve known.”

Phoenix’s broken schools — where resources are scarce, teacher turnover is high, and test scores fall far below average — often overwhelmingly serve students of color. A judge desegregated Phoenix schools 65 years ago, but public school enrollment data shows segregation has persisted and even intensified.

As one of these extremely segregated schools, where students of color account for at least 90 percent of enrollment, Garcia Elementary is hardly unusual. It exemplifies an ugly and mostly unspoken truth about Phoenix’s education system.

One of Tejeda’s students was recently disrupting class and trying to fight other students. Tejeda learned that his father was in jail and his mother had recently been deported; as a result, the boy had to move in with his grandmother.

“It’s a struggle every day,” Tejeda said. “It just depends on his mood, and what’s going on at home, and if he did eat.”

Giving students extra chances when they act out helps, she said, as does gently reminding them of her expectations. Almost 60 percent of people in the Murphy Elementary District live below the poverty line.

Despite the challenges, Tejeda’s roots in the neighborhood and memories of her first-grade teacher are the reasons why she has stayed. “The way she made me feel when I came to school — I loved coming to school. It was because of her,” Tejeda said. “I want to give that feeling to these kids, too.”

But the problems in the school district also have affected Tejeda’s family. Tejeda’s 11-year-old daughter was attending Garcia Elementary until this year. Concerned as a parent about high teacher turnover — her daughter went through four different teachers before January, Tejeda said — she transferred her to Lowell Elementary School, located two-and-a-half miles down the road in the neighboring Phoenix Elementary District.

(The Murphy administration did not respond to questions about teacher turnover.)

According to the most recent federal statistics, 63 percent of Phoenix’s students of color attend a highly segregated public school, and the vast majority of racially isolated students are Latino.

There are 172 Phoenix public schools where students of color account for at least 90 percent of enrollment. About 30 percent of these extremely segregated schools are charter schools and 69 percent are district schools.

There’s not a single public school where white students account for 90 percent of the student body. However, 28 public schools have a white student enrollment that is 70 percent or greater. Most are concentrated in north Phoenix near Scottsdale.

Because of Phoenix’s majority-minority student population — around 60 percent of public school students are Latino and 24 percent are white — white students often have fairly diverse classrooms.

But at the same time, thousands of students of color are consigned to schools that are overwhelmingly segregated. And by some standards, these students are not only relegated to classrooms where they’re racially isolated — they’re also receiving a worse education.

Test scores and school letter grades show poor performance at Phoenix’s highly segregated schools. At Garcia Elementary, for example, last year only 19 percent of students passed the AZ Merit English exam and 15 percent passed the math exam.

AZ Merit scores at Phoenix’s highly segregated schools fall far below the state average. Passing rates for the ELA and math exams were approximately 22 percent and 24 percent, respectively, at these 170 schools. At the predominantly white schools in north Phoenix, test scores were above the average passing rates by a wide margin.

Although people criticize the AZ Merit system from all sides, even when viewing the test as an imperfect yardstick for student achievement, these segregated schools are failing their students.

Research demonstrates that students at integrated schools perform better under almost every metric, according to the Century Foundation. At integrated schools, students are more likely to exhibit leadership skills and cross-cultural understanding. They’re less likely to drop out. And, most importantly, integrated schools achieve a more equitable distribution of resources and can help close the achievement gap for black and Latino students.

Even though nothing about a campus outwardly betrays the problem, segregation warps student outcomes at public schools like Garcia.

(Blue dots are public schools where 90 percent or more of the student body is nonwhite, and red dots are schools where 70 percent or more of students are white. Darker dots indicate a more segregated school population. For a complete statistical breakdown on each highly segregated Phoenix school, click the dot. Source: National Center for Education Statistics Common Core of Data, 2015-16.)

At BASIS Phoenix Central, the school was a hive of activity on the first day back after spring break.

“Hi, Ms. Thompson!” students in the hallway said brightly.

“Good morning,” Rosalind Thompson replied. “How’s your arm? Getting better?” she asked a boy wearing a sling. He just stared back.

Upstairs, sixth-graders in a world history class silently took down notes during a warmup exercise about Genghis Khan and the Mongols as their teacher paced the aisle. Down the hall in a brand-new P.E. room, a bearded martial arts instructor leaned on a punching bag at the front of the room and gave instructions to kids seated on the ground for a game of tag.

The ground floor of the building has been converted into a sports area where the concrete is covered in green artificial turf. The administration takes pride in its teachers, who deliver the rigorous curriculum, and Thompson pointed out that the P.E. instructor is originally from Australia. (“That’s why you can’t understand a word she says!” Thompson said conspiratorially, waving at the kids as they walked in a circle.)

“I hear it all the time from parents that they love the diversity of this campus,” Thompson said. She said that the school draws students from around 60 different ZIP codes: “It’s not just people that live downtown, or work downtown. They come from all over for the uniqueness.”

Students at BASIS Phoenix Central, part of a rigorous charter network, play a game of chess.

BASIS Phoenix Central

This year, BASIS Phoenix Central, with 854 students in grades K-8, has an enrollment that is 34 percent white, 23 percent Hispanic, and 29 percent Asian. The Latino population of the school is low compared to the surrounding community. According to the U.S. Census, 31 percent of residents of the school district surrounding BASIS Phoenix Central are Hispanic.

Asian students are just 2.8 percent of Phoenix public school enrollment, even though they account for a much larger percentage of BASIS Phoenix Central’s student body.

The same goes for other BASIS schools. At the charter network’s Phoenix high school, which serves grades 5-12, last year just over half of the students were white. Across Arizona, the charter network’s students are 38 percent white, 14 percent Latino, and 39 percent Asian, according to BASIS CEO Peter Bezanson.

“What we want is multiplicity of ethnicity, and we’ve got that here in a major way,” Bezanson said. Families are drawn to the school’s diversity and its reputation for academic rigor, he explained.

BASIS has also opened up schools in neighborhoods such as south Phoenix with the goal of having “a school within a reasonable drive time for every family.” The BASIS South Phoenix school is the only Arizona BASIS school that participates in the federal free and reduced lunch program.

“There are no barriers to entering a BASIS school,” Bezanson said. “The implication that it’s only for academically accelerated kids from families of means is something that we’re committed to destroying, because it’s not true.” Plus, there are thousands of kids on the waitlist to get into BASIS schools, Bezanson said.

He says he couldn’t alter the racial composition of the schools, even if he wanted to.

The racist housing policies that for decades determined where black and Latino families lived in Phoenix still echo through housing and education patterns.

Yet most top education officials and politicians never mention school segregation.

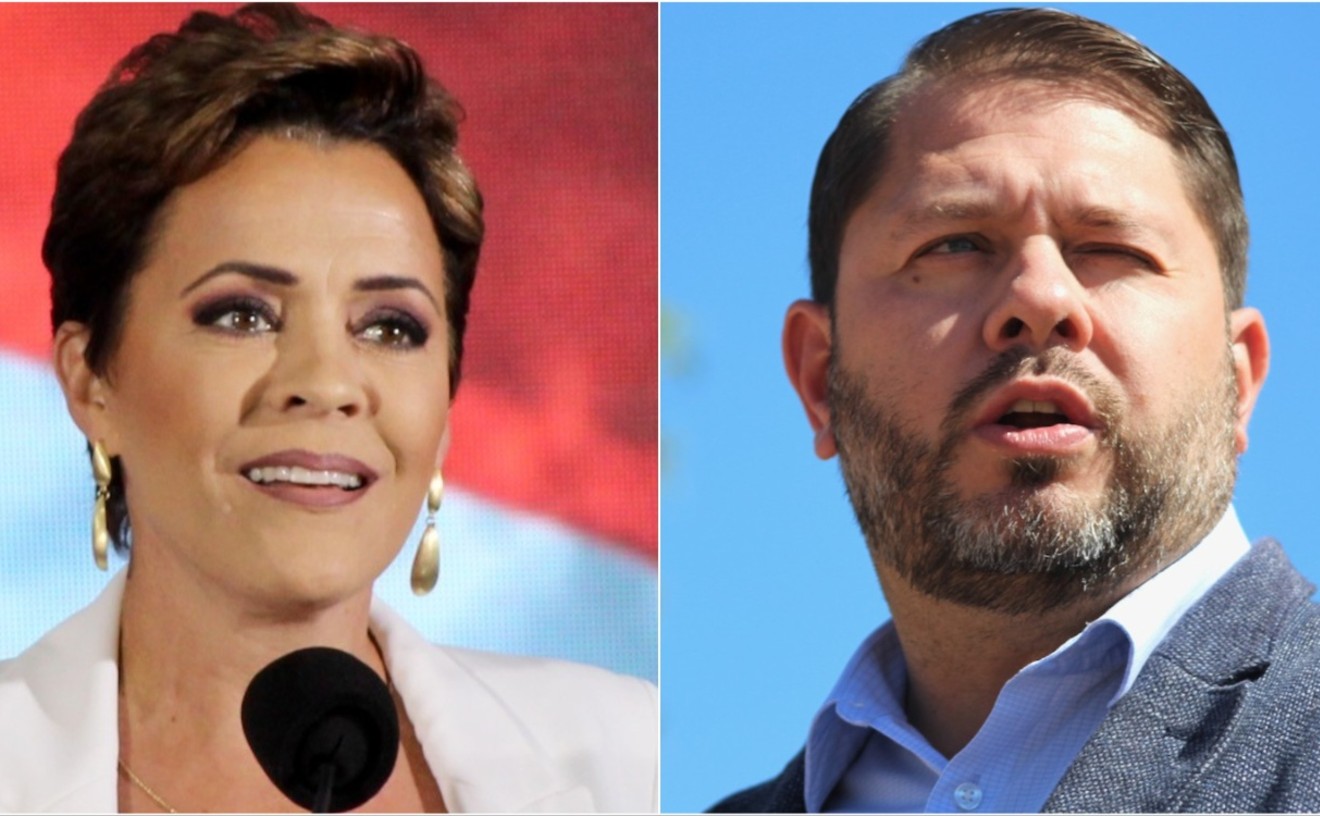

Gubernatorial candidate David Garcia also happens to be an authority on school segregation.

Joseph Flaherty

Garcia is a tall, energetic professor-turned-politician who is currently running for governor as a Democrat. He is an associate professor at Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. His research has focused on school segregation and the early years of charters in Arizona.

Because of his background in academia, in the course of his political career — Garcia narrowly lost a 2014 race for superintendent of public instruction — he was stunned to learn that school segregation is universally ignored by voters he met on the campaign trail, as well as education advocates and legislators alike.

“When I ran for office in 2014, not a single person brought up segregation,” Garcia said. “Not a one.

“I mean, we’re publishing on segregation over, and over, and over again,” he added. “Something is missing with respect to this academic conversation that we’re having that’s important. And the day-to-day policy discussion is void.”

It’s shocking compared to the amount of academic work on segregation, Garcia said. To prove the point, he asked a nearby staffer to pull up Google Scholar on their MacBook.

“Put in segregation,” Garcia said. There was a pause as his communications director typed.

“One point nine million results,” she said.

Garcia gave a look as if to say, I told you so. “There you go,” he said.

He said that school choice, income inequality, and the charter school explosion have made the problem worse. “We’re already segregated by race and income in housing policies,” he said. “And when you add school choice, it further exacerbates that segregation.”

He found that from 1997 to 2000, students left Arizona district schools where the average white student had 30 percent nonwhite classmates to enroll in charter schools where white students had 18 percent nonwhite classmates.

We already self-segregate in our lives, Garcia explained, surrounding ourselves with like people, especially in terms of socioeconomic class — education is the natural extension.

“When it comes to school choice, I think we’re asking a lot of people to have these tendencies in one part of their lives, and then when it comes to the education of their children, expose them to a lot more diversity than they have in their own lives day to day,” he said.

The Latino student population in Arizona has swelled from around 24 percent in 1990 to 45 percent today. White students are now the minority, and account for approximately 38 percent of Arizona’s public school students.

“With this demographic shift, I think it’s also served to deepen existing patterns of segregation,” ASU Professor Jeanne Powers said.

Powers is an expert on school segregation. Her research has shown that schools across Arizona are more segregated now than they have been in decades. The rise in the Latino population combined with intractable housing segregation has caused school segregation to intensify.

Today, according to research by UCLA Professors Gary Orfield and Patricia Gándara, Latino students in Arizona are triply segregated in a kind of Gordian knot, isolated in schools based on their language skills, family income, and ethnicity.

Historical enrollment data for Phoenix is sparse. The Arizona Department of Education said that it does not have school demographic statistics for years before 2001. But the existing data found in school district records, federal surveys, and archival newspaper reports bears out a story of intensifying segregation.

In 1994, according to federal data, Garcia Elementary enrolled 93 percent students of color; last year, the school reported enrolling no white students. The story at other public schools is similar. If they were segregated in 1966 or 1985 or 1994, they tend to be even more segregated today.

In 1966, according to an Arizona Republic investigation, 78 percent of the students at Lowell Elementary were Hispanic. Today, that figure is 87 percent. At Silvestre S. Herrera Elementary, 90 percent of students in 1966 were Hispanic; now, Hispanic students comprise 92 percent of the school.

In the Phoenix Union High School District, white families attending the district’s schools fled to the suburbs in the 1980s, according to the district’s enrollment statistics. The district now serves over 80 percent Hispanic students and less than 5 percent white students.

In 2005-06, almost 54 percent of Phoenix’s students of color attended an extremely segregated school. A decade later, that figure was 63 percent.

Because school demographics often closely track the neighborhoods where they’re located, the scars of housing segregation have a lasting impact, even after government-mandated segregation ended in Phoenix.

“I don’t know to what extent there was desegregation in order to have resegregation,” Powers said.

“Part of what happens with segregation is you can say, ‘We’re not going to segregate anymore.’ But if you don’t take any more affirmative steps to redistribute kids across schools, then you’ve basically frozen those patterns into place.”

And those patterns have been in place for a very long time.

George Washington Carver High School, once Phoenix's segregated school for African-American students, is now a museum and cultural center.

Patrick Bryant

But during that period of enormous change, there was one constant. From their earliest days in the city, Phoenix’s white residents were determined to segregate their African-American and Latino neighbors.

Arizona wasn’t even a state yet when lawmakers set about enacting school segregation with the force of law. In 1909, the territorial legislature passed a bill that allowed school districts to segregate black students. Surprisingly, Governor Joseph H. Kibbey attempted to block it.

Kibbey, a jurist from Indiana with a wiry mustache, had been appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt. In a prescient argument, Kibbey argued that school segregation was unjust. Consigned to separate schools, black students were bound to receive an education that was “less effective, less complete, less convenient, or less pleasant” compared to their white peers.

His plea fell on deaf ears. The legislature promptly overrode Kibbey’s veto, allowing school districts to segregate students by race. Phoenix’s school district began to segregate black students a year later.

When Arizona became a state in 1912, segregation was included in statutes at the constitutional convention with the full-throated support of the Southern racists in the Legislature. The law required elementary schools to segregate black students and allowed high schools to segregate students.

Separate elementary schools were constructed for African-American students. When an adjacent schoolroom for black students at Phoenix Union High School became too cramped, the school district built George Washington Carver High School in 1926 on the city’s south side, just off the railroad tracks. It’s now a museum and cultural center. (One of the segregated school buildings, Booker T. Washington Elementary, is now the offices of Phoenix New Times and other businesses.)

A quilt with squares representing alumni groups on display at the George Washington Carver museum.

Joseph Flaherty

Schools districts in Valley cities, including Phoenix, Gilbert, Tolleson, Tempe, and Scottsdale, segregated Mexican-American students to a different classroom or even an entirely separate school building during the elementary grades, according to Powers. The rationale was that splitting up white and Latino students benefited Spanish speakers who were in the process of learning English. Schools often segregated them for grades far beyond the early years of elementary school.

Of course, this underhanded form of segregation wasn’t about language. The system, which has been almost entirely forgotten, was punitive, harmful, and demeaning.

“You had to learn English, and if you were caught speaking Spanish, you got in trouble,” said Jean Reynolds, former curator for the Arizona Historical Society. “Language was a really big issue, and always has been.”

In the early years of the 20th century, it wasn’t uncommon for Mexican-American students to leave school after completing fourth grade, Reynolds said. Their families often needed them to work to earn money. But the Arizona school system also barred many Spanish speakers from accessing the same opportunities afforded to white children: Latino students who were able to attend high school were sometimes funneled into trade and vocational programs instead of taking more rigorous courses alongside college-bound peers.

Discrimination against Latinos in public accommodations was also common, betraying the supposedly benign motives for separating Spanish speakers in school. Just as Mexican-Americans were isolated in schools, they were segregated in swimming pools, theaters, and churches.

Moreover, Phoenix’s unequivocal policy of housing segregation applied to all nonwhite families, black and Latino alike. Van Buren Street was the racial dividing line. Before the 1968 Fair Housing Act, racist deeds and housing covenants explicitly barred any prospective homeowner who wasn’t white from purchasing property north of Van Buren.

Henry Watkins was among the black students who attended Phoenix Union High School in the first decade after desegregation. Now 72, Watkins graduated in 1964 and later became a judge.

Watkins remembers being routinely stopped and questioned by the police while running errands outside of his south Phoenix home. Public places downtown were segregated for most of his teenage years. When he went to see a movie, black patrons had to sit in the balcony.

“When I was a kid, you didn’t go north of Van Buren,” Watkins said. “I talk to people who were half a generation before me, and they say you didn’t go north of Washington (Street). You just didn’t go there. And indeed, I’ve experienced that.”

Racist housing policies also masked the true extent of Latino school segregation in Phoenix. Although there was no law on the books stopping Mexican-American families from enrolling their kids in all-white schools, those families couldn’t live near these schools in the first place. The chasm of Van Buren Street meant any schools to the north were white schools by default.

“They were ‘segregated,’ but they were segregated because it was about location,” Reynolds said.

Phoenix civil rights leaders and organizations like the NAACP, the Greater Phoenix Council for Civic Unity, and the Urban League fought to dismantle the system for years.

In the summer of 1952, lawyers Hayzel B. Daniels and Herb Finn filed suit in Maricopa County Superior Court to challenge Arizona’s segregation statute. It was something of a last resort. Arizona voters rejected a ballot measure to overturn segregation in 1950, but the following year the Legislature passed a law that allowed school boards to desegregate voluntarily. Yet Phoenix still refused to abandon segregation in the public high school.

One of the first African-American state legislators in Arizona, Daniels paid the $5 court-filing fee out of his own pocket, according to historian Mary Melcher. In his lawsuit, Phillips v. Phoenix Union High Schools and Junior College District, Daniels represented three black students who had been denied admission to Phoenix Union. The lawsuit said that segregation imparted “a stigma of inferiority.”

The schools for white students were “superior,” depriving the plaintiffs of benefits and resources they would receive in an “integrated school system free from racial discrimination and segregation.”

In a decision on February 9, 1953, Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Fred C. Struckmeyer overturned high school segregation in Arizona. For the Legislature to delegate the segregation to individual districts, allowing them to separate students on a whim, was clearly unconstitutional, Struckmeyer argued.

“A half-century of intolerance is enough,” Struckmeyer wrote. Elementary schools were desegregated thanks to a subsequent court challenge, also filed by Daniels. There were no protests against desegregation here, unlike the white backlash that wracked schools in the South.

The legal fight for equality in Phoenix’s school system, however, was far from over.

(School letter grades in 2016-17 are from the Arizona Department of Education.)

Phoenix never truly desegregated.

Because of the many scattered school districts here, paltry efforts at desegregation faced headwinds compared to other metropolitan areas, which made progress during the years after Brown v. Board of Education, until the 1980s and 1990s, when desegregation programs began to get rolled back nationwide.

During the civil rights era, Phoenix school officials mostly acted to combat segregation when compelled by a judge.

In 1985, the U.S. Office of Civil Rights hit the Phoenix Union High School District with a consent decree that stemmed from Castro v. Phoenix Union High School District. In the federal court case, plaintiffs argued that unequal resources within the school district and a plan to close several campuses had unfairly affected minority students. Latino students in particular would be relegated to inferior schools with fewer resources.

The OCR’s consent decree and the Castro settlement led to the development of magnet programs, the construction of two new high schools, and increased transportation for students, according to the Morrison Institute at ASU.

The district court lifted PUHSD’s desegregation consent decree in 2005. But school districts under desegregation orders or agreements with OCR can continue to raise revenue via property taxes for programs to combat segregation, and unlike bonds and overrides, districts aren’t required to seek voter approval.

Funding from the desegregation order makes up almost a quarter of PUHSD’s budget and has allowed the district to continue to operate several specialty schools and magnet programs. Yet conservative Arizona lawmakers have repeatedly tried to phase out desegregation funding, calling it outdated and unfair.

“When we’ve gone to the state Legislature and we’ve advocated, luckily, we’ve blocked these things in the past,” said Stanford Prescott, a member of PUHSD’s governing board. “But we hear segregation is over when it very plainly isn’t — not only when you look at the enrollment, but also when you look at the statewide academic achievement.”

Not everyone agrees.

Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction Diane Douglas would not describe Phoenix’s educational environment as segregated.

“I don’t like the use of that word because it was very different in this country when we had Jim Crow laws and ‘separate but equal,’ and those type of things,” Douglas said. “That’s what segregation means to me — the government saying, ‘You can’t be here because of your skin color or your nationality or your race.’ We’ve moved beyond that.”

Instead, she referred to the effects of socioeconomic division. “To me when I think of segregation, I think of a deliberate act to make that happen,” Douglas said. “But really it becomes socioeconomic, so how do we make not only just the young people, but even the families in these communities, how can we make them more successful?”

Title I, a U.S. Department of Education program administered by the Arizona Department of Education, provides funding to schools with a large percentage of low-income families. That is one way the state can address inequality, Douglas said.

“Potential is equally distributed, so what we have to make sure that we do, for our part of it in the education system, is to make sure the opportunity is also equally distributed so that all our students have a fair shake at a great education and to fulfill their potential,” Douglas said.

But just because, in theory, students have an equal opportunity to attend a BASIS school or a Garcia Elementary, can we call the system fair? Arizona’s free-market education reforms are supposed to allow students to enroll in the school of their choice. What about the cavernous opportunity gaps that stretch beyond the school entrance?

For some Garcia families, leaving is not an option. In a low-income neighborhood, they may not have the resources to get their kids to school. Arizona charter schools aren’t required to provide transportation.

“Say they don’t have a car to get there, or gas,” Garcia teacher Teresa Tejeda said. “A lot of them don’t have cars or ways to get around, so there’s no choice. Wherever you live, that’s where you’re going to send your student — to that school.”

Earlier this year, Tejeda had been teaching kindergarten, but one of Garcia’s two first-grade teachers quit midway through the school year. Tejeda took over the first-grade class and her kindergarten students were moved to another teacher, increasing the classroom size to nearly 40 students.

“A lot of parents have left because of the chaos,” Tejeda said. Former Garcia students have left to attend charter schools, such as the nearby Southwest Leadership Academy, although Tejeda is not sure how many. A decade ago, Garcia had 770 students. Last year, there were 485.

Last month, Monica Lopez’s daughter didn’t want to sit with her at a meeting of the Murphy elementary district board, which oversees Garcia. Instead, the first-grader raced to the other side of the room to see her teacher, Tejeda.

“She was antsy to go sit by her. She’s like, ‘Mom I want to go sit by my teacher.’ That speaks a lot about them,” Lopez said. She added, “They’re not just their teacher — that’s more like family.”

The 28-year-old is a third-generation graduate of the Murphy district. But the turbulence has left Lopez and other parents in the dark, worried about their children’s education. She brought her kids to an evening board meeting on March 8. The district was over budget, straining under a million-dollar shortfall mostly because of declining enrollment. They were staring down a state financial takeover.

“It would be very sad and heartbreaking for the schools to close, especially since they’ve been open for so long,” Lopez said.

As her daughter Leah chatted with Tejeda, Lopez’s third-grade son watched the meeting attentively. His younger brother was sound asleep, sprawled out on two chairs Lopez had pushed together.

The Murphy school board appointed Bryan Borden, an assistant superintendent for curriculum and assessment, to serve as administrator-in-charge to lead the district in the absence of a superintendent. Borden said that the goal was to keep schools open for the full year and ensure teachers get paid.

“I’m aware we have a little bit of a deficit here, so we’re trying to make the best of it,” Borden said. He said they intend to spend the budget as efficiently as possible, and consolidating schools is on the table. Despite the turmoil, Borden isn’t worried about the students in his district; the teachers have served as anchors, he said.

Lopez is less optimistic. For a while, she worried that the school would not be open after spring break. The state of the school left her heartbroken. She remembers that the district was more stable when she was a student.

“I’m hoping for a miracle,” Lopez said.

Wandering around the parking lot of Brooks Academy, I couldn’t find Janelle Wood. There was a sign for Wood’s organization, the Black Mothers Forum, but no sign of her. Then my phone rang, and I saw Wood waving at me from the gate to the campus of this former school in south Phoenix.

Wood, a former chief of staff for a City Council member, is the founder of the Black Mothers Forum. Her office is at the academy, which now serves as community offices and a greenhouse used in the Roosevelt School District. Thanks to her conversations with families, she’s probably as tuned in to issues of race in Phoenix schools as anyone you’ll meet, and often intervenes to advocate for parents and students.

“We want all children to have access to safe and supportive learning environments, period. And that is what we’re not seeing consistently in the districts across this Valley right now,” Wood said.

Wood said that students of color face a toxic learning environment, including discrimination and hurdles to access the best schools, especially charters. Upon enrolling, they’re forced to deal with implicit or overt prejudice from teachers and classmates.

Even more troubling to Wood are the disproportionate rates of discipline. According to federal civil rights data compiled by the ACLU, Latino charter high school students in Maricopa County are six times more likely than white students to receive an out-of-school suspension. Black students at charter high schools are eight times as likely.

Black and Native American students, as well as students with disabilities, are more likely to be suspended at both district and charter schools.

This disproportionate discipline creates a cycle, Wood explained. The most rigorous charter schools are hostile to students of color, forcing them into under-equipped schools with large class sizes and a shortage of qualified teachers. “When you have high numbers of people of color in one area, we lack the resources that we would’ve gotten in other areas that are predominately white schools,” Wood said.

In Phoenix, according to the most recent federal enrollment data, charter schools serve a disproportionate number of white students compared to district schools. White students are almost 24 percent of Phoenix’s total public school population, Hispanic students account for 61 percent, and black students comprise 7.2 percent.

But Hispanic students make up just 51 percent of students enrolled in Phoenix charters, while they comprise 63 percent of district school enrollment in the city. In contrast, white students make up 22 percent of district school enrollment and they make up 29 percent of charter enrollment.

Overall, students of color account for 75 percent of Phoenix district enrollment, while they comprise 68 percent of charter enrollment.

Charters enroll a slightly higher portion of Phoenix’s black students. African-American students are about 8.9 percent of total charter enrollment in the city, compared to 6.8 percent at district schools.

The demographics at high-performing and rigorous charter schools — like BASIS — are troubling to 35-year-old Luis Avila, the campaign manager with the ACLU of Arizona’s Demand 2 Learn campaign. Avila said that prestigious charter options often don’t reflect the demographics of their predominantly Latino community.

“What’s happening, then?” Avila asked. “Is it because Latino families, or families of color, don’t know of these schools? I don’t think so. I think it’s the fact that schools have suppressive practices to deny enrollment.”

Avila and the ACLU have recently zeroed in on unfair discipline and enrollment policies in Arizona charter schools. In December, the organization released a report entitled “Schools Choosing Students,” which described hurdles that students can face when trying to enroll in charter schools.

Some charter schools require essays and interviews, even if they aren’t used to determine who can enroll. Some ask questions about a prospective student’s disciplinary history. Some, including BASIS, encourage parents to make an annual donation to the school. Bezanson said that last year 39 percent of BASIS families donated after enrolling, but less than 10 percent gave the recommended donation of $1,500, which he said goes to teacher bonuses.

Other charter schools ask specifically for a child’s birth certificate without providing alternative options.

Whether these barriers are intentional, navigating them can be more difficult for students from low-income communities or immigrant families.

Elite charter schools can also push out kids who don’t perform through a process known as voluntary withdrawal — a conversation in which a parent learns their child isn’t measuring up academically or just isn’t the right “fit” for the school.

“If you’re a student of color in Arizona, it’s really hard to enroll in a high-performing school. If you get in, and you are not performing academically, they’re going to ask you to leave,” Avila said. “And they’re going to ask you to leave and you’re probably going to start acting out, and if you don’t leave, they’ll get rid of you either by suspending you or expelling you.”

The recent drive toward more performance-based school funding has also created incentives for more school segregation, Avila explained. English-language learners might drag down scores on the standardized tests that determine which schools receive extra state dollars.

All told, these factors can stack the deck in favor of white, affluent families, creating hurdles for students from marginalized backgrounds.

“We are creating a system that is picking the winners,” Avila said. “And those winners tend to look white, and those winners tend to be of more affluent families.”

For their part, charter proponents unequivocally deny that barriers affect who enrolls, despite the statistics that show a disproportionate number of white students are taking advantage of Phoenix charter schools.

Eileen Sigmund, the president and CEO of the Arizona Charter Schools Association, said that innovative charter options are gradually expanding to serve Phoenix’s “urban core,” and emphasized that charter schools outperform district schools on state exams.

“There’s a big difference between government-imposed segregation and what is happening in Arizona, which is Arizona families self-selecting into schools they believe best meet their children’s needs,” Sigmund said.

She rejected the idea that fault lines of income inequality and housing segregation influence how marginalized students access charter schools.

Sigmund said, “I absolutely disagree that there’s barriers, because our charter schools only keep their doors open if students and families choose to attend our schools, and if they meet a high accountability standard and metrics by our authorizer.”

That’s a common perception — that the system is working.

Spend enough time talking with the influential, agenda-setting individuals in Phoenix who make decisions in education, and a discussion about one thing segues to something else.

A conversation about school segregation becomes about parental choice, or providing equal opportunity, or Title I funding, or small pockets of improvement. But very few of these powerful people want to name, much less address, a problem that has plagued generations in Phoenix and appears to be alive and well.

Ask them why, and they’ll say that the problem has already been solved. Why even bring it up?

The same conversation echoes through Phoenix’s past. Even after government-imposed segregation ended, people struggled to make the government aware of de facto racial injustice in education — trying to make an invisible problem visible.

In February 1962, almost a decade after de jure school segregation was overturned in Phoenix, federal officials on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights visited the city as a part of the agency’s assessment of the progress of civil rights. Leaders of the city’s African-American, Asian, and Mexican-American communities addressed the fact-finding panel.

The commission members wanted to visit Phoenix in part because of its tremendous growth, and because they were under the impression that the Phoenix of 1962 had made progress in civil rights and equal protection even though it had few, if any, anti-discrimination laws on the books.

Speakers tried to correct them. Then-executive director of the Phoenix Urban League, Charles F. Harlins addressed the commission. In his written testimony, Harlins said they shouldn’t take the absence of open racism as “an indication that there is no race problem in Phoenix.” Nothing could be further from the truth, he said.

Harlins laid out the discrimination facing minorities in employment and public accommodations, and recommended that federal officials carefully examine the ongoing de facto segregation happening in Phoenix’s education and housing.

“These are some of the problems that will be solved only when the community recognizes the waste of manpower, the economic loss to the city, and the incompatibility of these problems with professed democratic ideals,” Harlins said.

More than half a century after Harlins’ warning, Phoenix has somehow managed to square the incompatible. Professing democratic ideals, we ignore or throw up our hands at a moral failure in the most important arena of opportunity in a person’s entire life.

In a final warning that he posed to the commission, Harlins referenced the Phoenix of the future. These problems will continue to exist, he said, unless the community cares enough to do something about it.

Email [email protected].