Naturally, Phoenix police were taking any tips they could get. So when Allison DuBois called wanting to talk, they listened.

DuBois' name might have sounded familiar to the cops. That summer, season two of Medium, the television series based on her life and alleged psychic powers, had just wrapped. Patricia Arquette, her TV alter ego, had won an Emmy for her work on the show's first season.

Detective Alex Femenia, the lead investigator in the "Baseline Killer" case, followed every tip he got. But DuBois led him nowhere.

DuBois says she called the detective because a mutual friend at the County Attorney's Office asked her to.

At the time, she said in three separate media interviews that the Baseline Killer had possibly fled to California and that he had facial features not tied to any race, and skin that was dark but not necessarily black. DuBois couldn't get as much info on the "Serial Shooter" because he didn't make contact with his victims. (She says she profiles people by getting inside the heads of both the criminals and the victims.)

She said she could "feel" the length of the Baseline Killer's hair, saying it was long enough to tuck up under a cap. She felt he had issues with his mother. She felt the killer would be arrested in August.

Well, she was close on that last one.

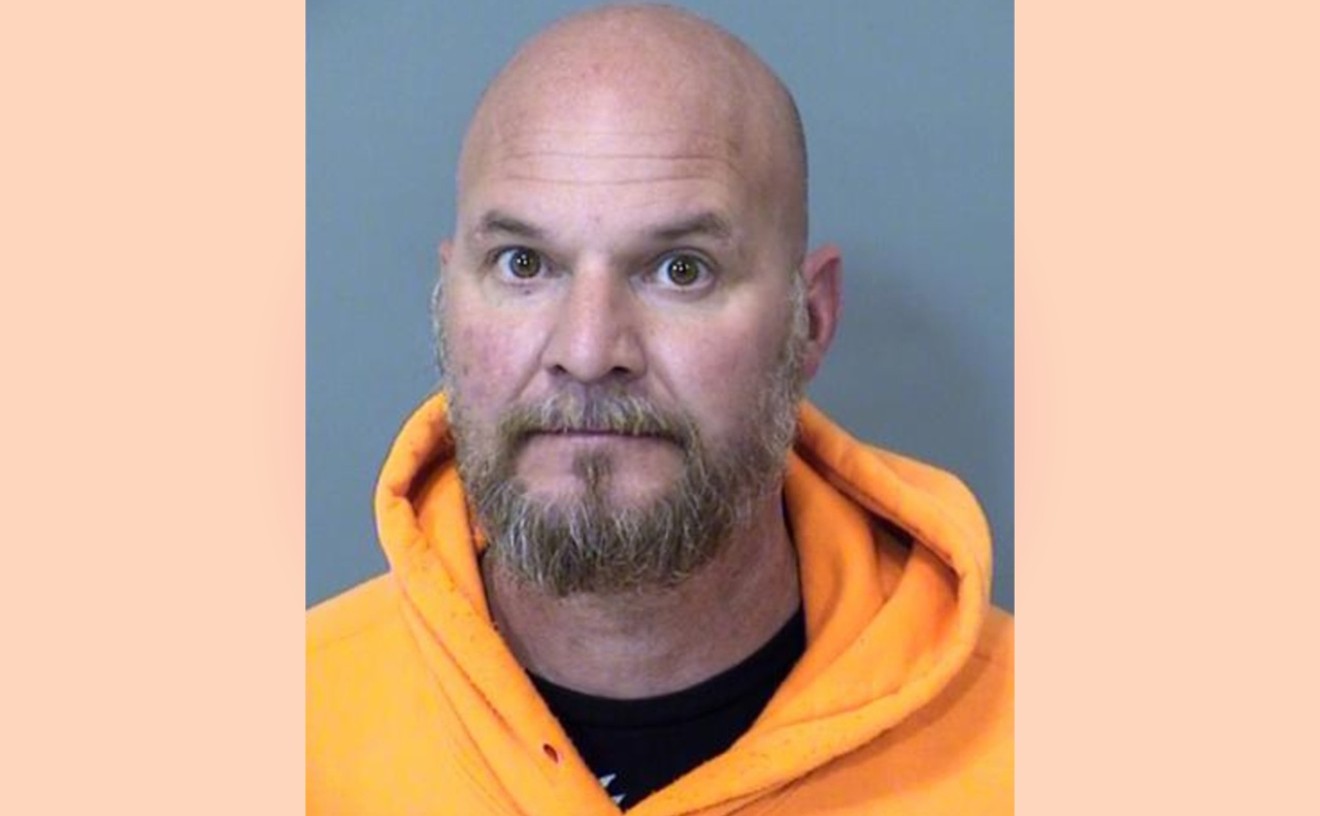

In early August 2006, police arrested two white men, Dale Hausner and Samuel John Dieteman, and charged them with the serial shootings. On September 4, the Phoenix Police Department arrested Mark Goudeau, an African American construction worker with short hair, living in Phoenix. In December 2007, Goudeau was convicted of sexually assaulting two women. He is scheduled to stand trial on 74 additional charges, including nine counts of murder.

Dieteman has pleaded guilty to two counts of murder in the Serial Shooter case, and Hausner awaits trial on eight counts.

Police generally refuse to talk about ongoing cases. But when New Times called to tell them about DuBois' latest book, Sergeant Andy Hill made an exception.

Chapter Two of Secrets of the Monarch, published last year, details her take on the Baseline Killer case, including her impressions of the suspects, her anger over how her city was under attack, and her desire to help close the case. To be fair, DuBois does credit the police department with cracking the case, though she says the arrest timeline she gave them was important.

Hill says that according to both the lead investigator, Femenia, and the lead supervisor on the case, DuBois had nothing to do with catching Goudeau.

"Sometime during the sequence of crimes, the lead investigator said that, to his best recollection, he had two conversations with Ms. DuBois," Hill says. "It seemed to him that Ms. DuBois was trying to get information from him. But the only information she suggested was one statement that was totally incorrect, stating she thought the suspect was a transient and had left the state."

That's the thing about DuBois. She's charismatic as hell, and most definitely has friends in high places, but when it comes down to high-profile cases she claims to have worked, the cops and the family members of the victims deny she was any help.

It's been two years since the Baseline Killer terrorized her city, and Allison DuBois has never been more popular. Her show is entering its fifth season of production, she's touring the country with Secrets of the Monarch, and she's begun teaching private classes — at $150 a session — on how to tap into one's psychic abilities.

Her fans don't care whether the police say she never worked with them or whether families of crime victims say her predictions are inconsistent. DuBois shrugs off the criticism, saying denial is par for the course. She fashions herself as much a publicist as a psychic. In the Baseline Killer case, for example, she says she was just trying to raise public awareness.

"It's not always in my hands to solve something, but I can at least get people to look at their neighbors," she says.

DuBois has an almost mesmerizing way of explaining away her mistakes, and she's managed to keep both her erroneous predictions, and her naysayers, largely confined to Internet forums.

She's built a nice empire for herself: three bestselling books, a packed tour schedule, and the reason you know her name — an Emmy-winning, highly rated television show purportedly based on her life.

For this story, DuBois and her husband were interviewed extensively, as were the families and friends of people she's written about and representatives of agencies she says she's worked with. DuBois opened up as much as she ever seems to open up — even allowing her three kids to be interviewed — but much of her private life remains private. Background for this story also came from her bestselling books, a book written about her by Tucson parapsychologist Gary Schwartz, and the show Medium.

The truth is, in the cases New Times examined — from the one that got her started to a high-profile murder last year — questions about DuBois' involvement (or lack thereof) emerged.

In March 1999, 6-year-old Opal Jennings was abducted from an empty lot near her grandmother's home in Tarrant County, Texas. DuBois claims she was called in to work the case by the Texas Rangers, who subsequently denied her involvement.

More recently, DuBois worked the case of 19-year-old Jackie Hartman, who disappeared from Gilbert in late January 2007. Her body was found a month later. Though DuBois went on The Oprah Winfrey Show to talk about the case, she did little to find Hartman's body or catch the man who killed her, says Dave Hartman, the woman's father.

Even the story behind the death of a friend, featured prominently in all three of her books, is disputed by the sister of the deceased.

But there are scores of devoted DuBois fans (including a professor at the University of Arizona who studies psychics) who swear she's the real deal, that she's personally contacted their dead loved ones.

These people aren't alone. According to a 2005 Gallup poll, 41 percent of Americans believe in extrasensory perception.

And no psychic, from Nostradamus to Sylvia Browne, has a perfect track record. DuBois is certainly in well-known (if not always correct) company. She's no Oracle of Apollo, but thanks to Medium, she'll at least go down in pop-culture history.

In the TV series, the DuBois character receives her visions while she's dreaming, the same way Samuel and Joseph did while working for Old Testament kings and tyrants. In the 1500s, Nostradamus is purported to have predicted many modern-day events — the JFK assassination and the terrorist attack on the Twin Towers, for example. But like DuBois', his predictions are extremely controversial. An entire branch of academia exists to debunk him.

Today, psychics are split into two factions. You've got Miss Cleo and her army of 900-number fortune-tellers on one hand, and people like John Edward, Sylvia Browne, and Allison DuBois on the other.

The Edwards and Brownes of the world — and, most notably, DuBois herself — have built reputations thanks in large part to parapsychologist Gary Schwartz and television shows that bring their supposed abilities to the masses.

Also thanks to TV, DuBois comes with a high price tag. In February, fans went to the Mesa Arts Center and paid $75 a pop to hear her lecture on what it's like to talk to dead people and how fans can attempt to make contact with their lost loved ones.

Onstage, DuBois looks good in her jeans, boots, and black blazer. A box of Kleenex is strategically positioned next to her seat for whomever she will bring onstage later. Her signature red hair looks like it's on fire as she lists her accomplishments for the crowd and makes distinctions between her real life and the one portrayed on TV. The biggest similarity is that she has three kids and a husband named Joe (though he was George until two years ago). She owns a gun. She relishes the thought of sending "bad guys" to death row.

Toward the end of her presentation, she brings a man onstage to talk to him about his dead wife and children. The way she does the reading, it sounds like a conversation between friends, but the man obviously believes what she's saying about the messages his loved ones are sending from beyond.

DuBois doesn't look like someone who suffers skeptics kindly, and she says as much a month later over swordfish at the Rokerij steak house in central Phoenix.

"I'm spiritual; I'm not a doormat," she says. "I'm from Arizona. I wear boots. I'll give you a little kick."

DuBois developed her tough-talking attitude early in life. Her childhood was not an easy one. It's a topic she obviously avoids, except as it relates to the psychic experiences she claims to have had as a child.

Her parents, Mike Gomez and Tienna DuBois, divorced when she was a baby. Tienna remarried and divorced again when Allison was 12. In her first book, DuBois writes about seeing her stepdad in public with his new family.

"He didn't see me and I never saw him again."

A self-proclaimed daddy's girl, DuBois didn't get to spend much time with her late father (he passed away in 2002), either. She wrote about seeing him on Saturdays only. Court records from May 1976, when DuBois was 4, reveal a child-support dispute. (Attempts to reach Tienna DuBois, including through Allison and Joe, were fruitless.)

DuBois says her first experience with her "abilities" — her term for what she does as a psychic/medium — came when she was 6, on the day of her grandfather's funeral. She says he appeared at the foot of her bed and asked her to tell her mom he was okay.

Her mother did not believe her. But DuBois says her late maternal grandmother was also a medium. She believes it's genetic and says her three girls have abilities as well. She remembers playing games with her grandma that were designed to hone her skills.

"You can see it in children. I saw it in mine. So, she always knew. She was accepting of it," she says. "We would play Wheel of Fortune and I'd name it before the letters were turned."

DuBois' childhood sounds lonely. She writes about spending time with her stuffed animals but rarely about spending time with friends. The two things that seem to have gotten her through were competitive roller-skating and her overwhelming desire to be a lawyer.

"All I wanted was to be a prosecuting attorney. I carried a briefcase to school. I wore navy blue sweaters and navy blue culottes and penny loafers," she says. "I was such a dork, but I felt it was a smart look."

She talks often about her unrealized dream — and is overjoyed that her oldest daughter, 13-year-old Aurora, has expressed a similar ambition.

Her familial relationships were always strained, especially on her father's side, and remain so today.

"Honestly, my father was Hispanic and my mom was German. She was tall and beautiful and everything they hated. On that side of the family, nobody seems to be happy for you when you go anywhere in life," she says. "We haven't seen them since my dad died."

There's an exception. A cousin from her dad's side of the family recently took over her husband's job as her manager.

"He's the only reason I don't need a DNA test to know I'm related to those people," she says.

By the time she was 16, DuBois had moved out of her mom's house because of a conflict with her stepfather. Though she attended both North High School in Phoenix and Corona del Sol in Tempe, she graduated from neither. Instead, she dropped out and got her GED at 16.

The longer she lived on her own, running with a party crowd, the less she thought about her future. Domenic Skala, a friend of DuBois' since she was 16 and the ex-husband of her late friend Domini (more on her later), remembers thinking that DuBois didn't really fit in with their crowd of underage boozers and partiers.

"I told her, 'This isn't your crowd.' It wasn't a rough crowd, but it was a party crowd," he says. "She just seemed like she had more potential."

DuBois agreed.

"I remember kicking back with a beer and thinking how ludicrous it was that I had once told my sixth-grade teacher that I aspired to go to Harvard," she writes in her first book, Don't Kiss Them Goodbye. "At this rate, I wouldn't even be going to community college. My teenage years were painful and lonely."

And they might have stayed that way if she hadn't met her future husband, George Joe Klupar.

(In 2006, according to Maricopa County Superior Court documents, the family legally changed its last name to DuBois and Klupar switched his first and middle names. She says they made the changes because Klupar was such an unusual last name and Joe's family was being harassed.)

They first met at Gators, an old Tempe sports bar. Joe thought she looked like an angel, a pool table light shining down on her head. Allison was much less impressed.

"I thought he was cute, but I thought he was annoying. And he grabbed the back of my skort — skorts, I know; it was the '90s — and I looked at him and said, 'If you ever touch me again, I will make your life a living hell," she says, smiling at her husband, remembering the first words she said to him. "He kept sending me beer and I kept sending it back."

But the "annoying" aerospace engineer talked her into a date. He took her to the Pink Pepper in Mesa and, again, Allison was not impressed.

"He talked about his ex-girlfriend the entire time," she remembers.

She didn't plan on going out with him, but he kept calling, and by October 1993, they were married.

"Aurora was born nine months later. She still does the math, and I'm, like, 'You were a week early. Shut up,'" DuBois says, laughing.

She settled down immediately to raise her little family. She drifted apart from old friends and started to think about her legal dreams again.

She enrolled in school, first at Mesa Community College and then at Arizona State University, where she majored in political science and made plans to go to law school. In between, she had her other two daughters, Fallon and Sophia. She was a full-time student and a full-time mom, but her life as a full-time medium had not yet begun.

She graduated from ASU in 2000 and, in her last semester, she interned for the Maricopa County Attorney's Office. She says she still maintains friendships in the office and has consulted on juries for at least one trial.

As of press time, the County Attorney's Office had not answered a request to confirm that claim.

She was excited to get the internship — her dream of working as a prosecuting attorney felt within reach. Even with all the success that came to her after the internship was over, she mourns the loss of her dream.

"It's hard," she says. "I have friends who are district attorneys, and they say, 'You'd be a great prosecutor. We wish we had you with us.'"

And she probably would be. She's persuasive, aggressive, and smart. But she says that because of her abilities, it wouldn't be right, especially because her long-term goal was to become a Superior Court judge.

"How could I be an impartial judge? I can't if I know they're guilty," she says. "I would have to do something that's probably not legal to make sure they don't come out. That's not right. That's not the law."

Her time at the County Attorney's Office is probably one of the best-known parts of DuBois' life, because it's a major part of Medium's plot. But there are some big differences between what she did in real life and what the character does on TV.

Former Maricopa County Attorney Rick Romley, who was in office when DuBois was an intern, says he never met her. But after the show came out, he got plenty of calls.

"I was a little surprised," he says. "The context by which the show was done was that she solves crime. I remember being told she was being used as a jury expert."

In the pilot, the intern DuBois is shown giving a presentation about the brutal murder of a young mother and her baby and offering her opinion on what happened. Obviously, that's beyond the scope of DuBois' real-life internship, where she says she sorted crime-scene photos and filed papers. The show is based on her life but never claims to be completely accurate.

She does say that her contact with the photos gave her flashes of intuition like the ones seen on the show. She says that when she touched the photos, she could see the crimes as they happened through the eyes of the perpetrator and victim. She doesn't have visions in dreams the way the TV Allison does.

"I could see what was happening before the person was killed," DuBois says.

She says victims show her symbols or words that are clues to where their bodies are located and what happened to them, but it's easier if the killer actually had contact with the victim. She also says she can read the minds of perpetrators — she calls it head tapping.

During her internship, part of DuBois' job was to organize files on missing and exploited children from around the country. A file on 6-year-old Opal Jennings, a child who disappeared from her grandmother's home near Dallas, landed in her hands.

She says the case is what led her to send a letter to law enforcement officials in Texas with information regarding the disappearance. She then was invited to go to Texas to meet with the authorities there.

DuBois says she worked with the Texas Department of Public Safety (nicknamed the "Texas Rangers") and showed them places where the body might be buried. She did this in August 2000, a year after the perpetrator, Richard Lee Franks, confessed and was taken into custody and two months after his first trial ended in a mistrial. In September of that year, Franks was convicted at his second trial and sentenced to life in prison.

The little girl's remains were not found until 2004. DuBois says she narrowed the location to a square mile, but because Texas DPS has denied ever working with her, there's no way to prove or disprove her statement.

In a 2006 television interview, a sergeant with the Tarrant County Sheriff's Department, which worked the Jennings case in conjunction with DPS, told Paula Zahn that he remembered DuBois' offering her impressions about the case.

"But [he] also downplayed your efforts," Zahn told DuBois. "He ended up saying that any information you gave him was pretty darn generic and wasn't that helpful."

DuBois says she's used to law enforcement denying her involvement in cases, as police officers in Texas and Arizona have.

"I don't want anyone getting an appeal because I'm in a courtroom," she says. "Which is why I don't do it anymore. I'm a celebrity. I could throw a jury one way or another, and you can't do that. They'd be, like, 'She's here. He must be guilty.' Which I'm okay with. But it's not lawful."

Part of the reason her involvement isn't widely touted could be because, as in the Baseline Killer case, she's just one of many tipsters who call the police. And she's not the only medium calling in. On high-profile cases, the cops get hundreds of so-called psychic mediums coming to them with information.

Regardless of what really happened in Texas, after working the Jennings case, DuBois felt called away from her dream of becoming a lawyer. Instead, she wanted to find out if she could be a medium.

She heard about Gary Schwartz, a professor at the University of Arizona who was conducting research on mediums in his lab. Schwartz had garnered national attention after appearing in the 1999 HBO documentary Life After Life. (The cable television network totally funded the research he conducted in the documentary and also supplied him with the mediums he tested.)

Allison decided to pay him a visit.

"It came down to the laboratory. I said, if I can do something in the lab that makes me great — better than most — I will give up my dream to do my calling," she says. "That was a turning point."

And she proved a force to be reckoned with in the lab, leading Schwartz to declare her "the Michael Jordan of the mediumship world," something he stands by today, though the two are no longer on speaking terms.

Schwartz's experimental designs are criticized by the scientific community, and his work is not sanctioned or paid for by either the university or the government. Still, within the context of his laboratory, DuBois was clearly a superstar, shining as brightly as established psychic luminaries like John Edward and Lorie Roberts.

In 2001, Paramount Studios contacted Schwartz's lab to talk about a new show it was producing. The show, which would be called Oracle, would feature five people with psychic abilities who would give readings for members of the audience, similar to John Edward's hit Crossing Over. Paramount wanted to know if any of Schwartz's research mediums were interested in auditioning.

DuBois was.

She auditioned by giving a reading over the phone for one of the show's producers before flying to L.A. to audition in person. She was competing with 118 people, hoping to become one of the five oracles.

"I don't play well with others," she says. "The producer pulled me aside and said, 'We're like a family here.' I said, 'I don't get along with my own family. Don't ask me to do that here. I'm here to smack down and do what I do.' That's just my personality."

Though DuBois made it to the final five, the pilot never aired.

"I could see why it wasn't picked up," she says. "They didn't follow my advice."

But DuBois had made quite an impression on one of its producers: Kelsey Grammer. A year and a half later, Grammer's assistant called DuBois to see whether she'd be interested in working with him on a show based on her life. It would be fictionalized, but the characters would be based on her and her family.

She agreed.

Shortly after Medium debuted in 2005, Schwartz came out with a book provocatively titled The Truth About Medium. Really, it's the truth about Schwartz's research methods, but he does frame each chapter around DuBois, whom he calls a powerful medium.

The book showed DuBois in a positive light, but she was pissed. She says she asked him not to write it and that when he did, she stopped allowing him to test her. They are no longer on speaking terms. She says it angers her that someone would try to profit from her abilities.

Schwartz will not comment on DuBois, even to defend himself, preferring to talk only about his experiments.

He's not talking, but her naysayers are. Though she has many fans, she also has many people who have devoted their lives to debunking her. DuBois describes them as "angry, old white men with abandonment issues."

And they, in turn, describe her as a "hypocritical asshole" and the "queen of questionable mediums," while her fans are "credulous ass-hats," loons, and nut bags.

One organization of skeptics, the Two Percent Company, even declared an "Allison DuBois Week" in 2005 during which they published a different article each day of the week debunking her. James Randi (a.k.a. "The Amazing Randi"), a magician and professional skeptic, has offered DuBois, or any other psychic, $10 million if she can prove her abilities in a test that he would design.

She hasn't accepted the offer. No one's ever passed his test.

DuBois doesn't see what Randi and others are so upset about.

"The big argument is that we're tricking people out of money. Our clients don't think that. They're very happy.

"I don't know who you're speaking for," she says to her critics. "You're spinning your wheels, wasting your time on people who want to get help."

After Medium debuted, DuBois began publishing books that were part memoir, part self-help manual. In them, she offers advice on dealing with the death of a loved one, relays her experiences as a psychic, and talks about predictions she's made that she says have come true.

In her first book, Don't Kiss Them Goodbye, she writes about a childhood friend, Domini Sitts, whose death she claims to have predicted when she was 19, when she told Sitts to quit smoking.

Sitts is the friend she lived with after she moved out of her mom's house and into an apartment. DuBois recalls watching Beaches together and promising to care for Sitts' kids if she died young.

Her younger sister, Karen Sitts, remembers their friendship differently.

"She's pretended this relationship with my sister, but they were anything but best friends," she says. "They were friends, but the kind that got into fights all the time. She and my sister had a falling out and didn't talk until she was dying and got back in touch."

Quite different from the romantic way DuBois writes about their friendship in her book: "We cried together, we laughed together, and, when it was time, we said goodbye together."

Domini Sitts has appeared in all of DuBois' books and she talks about her in interviews as well. During a 2005 radio interview, she expanded upon the Sitts storyline.

"The thing that was nice was, I was able to take her fear away," she says. "And when she was getting ready to pass she was, like, 'You're right. I can see my grandfather, and I know that they're there.' It was very important to me that she knew that before she died."

Karen says it's all a lie. Her sister died of malignant melanoma, and her death, as she describes it, was gruesome. Domini saw no one but family in the months before she died and, two weeks before her death, entered a drug-induced coma that she never came out of. There was no wide-eyed deathbed vision.

"I want to clarify: The last time Ali saw Domini she was still walking around," Sitts says. "She was cognizant and was nowhere near dying."

Sitts says her sister was terrified of dying because she thought she was going to Hell. She held on to life to the point that her body began to decompose.

"I want to stress what a terrible state my sister was in when she died. Because if Allison had known, I'm sure she would have written something about that. But she wasn't there," she says. "The day she died, we were washing her and her ass actually came off. You could see her bones. It was the worst thing I've ever been through in my life. When Allison writes about my sister's death, it's really romanticized, and the fact of the matter is, it was ugly and painful."

DuBois says Karen Sitts is absolutely wrong. She says the only reason she wasn't around during hospice was because the family wouldn't let her in.

"If they weren't there every day of my life, and every day of her life — which they weren't — they can not call into question my affection for Domini," she says. "It's frustrating. I memorialized her, and half the world is in love with her and praying for [Domini's daughter] Marissa. That's all positive. I don't see how that could make them angry."

Domini's ex-husband, Domenic Skala, who took care of Domini through much of her illness (she moved into his apartment), corroborates DuBois' story and says she's also gone out of her way to care for Marissa in the years since the death of her mother.

Dave Hartman also knows what it's like to have DuBois write about the painful death of a family member. In her latest book, she writes about his 19-year-old daughter Jackie, who was found slain in February 2007.

On January 28, 2007, Jackie was believed to have been murdered by a man she went on a date with. The nursing student at Chandler-Gilbert Community College had never been on a date before.

She was not confirmed dead until her body was discovered in the desert outside Fountain Hills almost a month later. Police have charged Jonathan Burns with the crime, and his trial is likely to begin in January.

DuBois dedicates an entire chapter to her supposed role in finding the body. She claims to have been contacted by a family friend and asked to help.

"The clincher for me was Jackie's dad. I saw him on the news, and he had so much love in his eyes for his daughter, and I could feel his heart break," she writes.

Dave Hartman has never met or spoken with DuBois. Until he was contacted by New Times to comment on the chapter, he didn't even know he'd been included in her book.

He thinks she saw a lot of things on the news. In his opinion, all the predictions she made about his daughter were gleaned from nightly news updates on the high-profile case.

"I thought it was a bad interpretation of the truth," he says. "I had 60 or so of these so-called psychics and every one of them was so far-fetched. I don't mean to poke judgment, but a lot of things she says [are] wrong."

After Jackie disappeared, DuBois appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show to talk about the case. A camera crew followed her as she went to the gas station where Jackie was last seen. She predicted that the girl rolled down an embankment after she was killed and that there was a city limits sign nearby, but she did not give any more detail. The former didn't happen, and there was no city limits sign near where Jackie's body was found, according to Hartman. DuBois says she does not like to give the bloody details of a case, out of respect for the family.

Hartman was asked to go to Chicago to sit in Oprah's studio audience and hear what DuBois had to say about his daughter's disappearance. He didn't mind the publicity for the case, but he declined to appear.

"We were doing searches. I had better things to do," he says. "I couldn't afford to take two days off searching and I thought it was silly to put pressure on me to tape. I had enough facts to work on."

DuBois told the camera that she was being "shown a funeral." She also predicted the girl's remains would be found in two weeks.

She was right about just two things: Jackie was dead and she was found within two weeks of the broadcast. That's it. Hartman wasn't impressed. With almost 600 people searching for Jackie each day, he says it was just a matter of time before she was found. And when the suspect's truck was recovered, with Jackie's blood inside it, he became certain his daughter was dead. He didn't need a psychic to tell him that.

His best advice for parents of missing children is to put together highly organized search parties — and to avoid psychics.

"Don't fall into that crap. You'll drive yourself crazy," he says. "They all claim they're not trying to get famous and as soon as they can, they all write a book."

Criticism like that is something that DuBois has learned comes with the territory, but it bothers her to be lumped in with the other psychics who contacted Hartman directly.

She says it's true she never met him or spoke to him — but says that was purposeful.

"A lot of people say things that the family doesn't need to hear. Which is why I never work directly with the family. I work with extraneous family members," she says. "I don't like being clumped into the psychics that called him. And I think I did a good job actually. I think I was very respectful of her."

Criticism certainly hasn't affected DuBois-related book sales, television ratings, or lecture attendance around the world. DuBois doesn't feel especially compelled to convince people she's for real.

"That's not my job," she says. "This is what I share with people who understand."

Medium just completed its fourth season with an estimated 10.4 million viewers. Season five is slated to begin in January. As the show has become more popular, interest in the real Allison DuBois has increased. And that suits her fine. She's easily settled into the life of a minor celeb — not a hard thing to do when you're summering in the Hamptons with Kelsey Grammer.

But she says the high life has had some pitfalls. Her oldest daughter has had some trouble at school. One boy was harassing her so badly, she says, that her family decided to move to a different school district next year.

DuBois' other two children, Fallon and Sophia, say they haven't experienced any teasing since moving from private school to public. In fact, they like it better because they have more freedom.

"You couldn't even wear, like, purple shoes," Fallon says scornfully of her old school.

DuBois has written about her daughters' psychic abilities — also part of the show — but if they do have the gift, none of them is interested in going into the family business. Aurora says she might go to law school, which thrills her mother. Fallon just started playing the piano and wants to be a singer. And Sophia says she'd like to be a butterfly or a "crazzzyyyy monkey," before dissolving into a bout of third-grade giggles.

As for their mother, she says she's decided to quit working cases. They've taken too much a toll on her, and she says she's also tired of answering the "why do they deny you've worked for them" question.

DuBois was extremely agitated to hear what Phoenix police had to say about her involvement with the Baseline Killer case. She had a similar reaction to the way Dave Hartman responded to her work. She says that is exactly why she wants to leave police work behind.

"I need a break. It's frustrating," she says. "I'm frustrated by the whole system."