We have our taco stands that grill carne asada into the predawn hours; family-owned greasy spoons open at sunrise with eggs and toast; fresh seafood trucked up from Puerto Penasco; the neighborhood fine dining with organic vegetables; the French; the Italian; the nuevo American; the old style Tex-Mex with the rock and the salt and the cilantro-inflected everything.

True enough that the state — like most of the Sun Belt — also is blanketed with the ezcema of corporate monoculture, marked by so many colored plastic spindles stuck outside like flags announcing the presence of an invading army. And not every locally owned restaurant distinguishes itself; some are downright bad.

The restaurant business is notoriously tough: high startup costs, thin margins, unpredictable cycles, obnoxious customers, high employee turnover, long hours. Natural selection tends to weed those out who have no heart for the struggle.Anglos who rushed to exploit gold, silver, and copper deposits in the 19th century at hell-on-wheels camps like Tombstone, Bisbee, Wickenburg, and Oatman brought with them a distinctive Southern taste: bacon, gravy, cornbread, peaches.

tweet this

Which is why the true survivors deserve special recognition. In the complicated ecosystem of Arizona restaurants, there are a few that have earned iconic status, some through sheer perseverance. Their endurance reflects the appreciation of their communities. Either through the food, the image, the atmosphere, or the connection to local culture, the iconic restaurants of Arizona all “say something” about the surrounding landscape.

They also represent a patchwork of historical influences, for there is no one established “Arizona cuisine.” Not even our Mexican food — arguably our boldest signature to the visitor — has as mature and recognizable a regional distinction as that offered by New Mexico or even Texas.

Certainly the oils, chilies, tomatillos, and meat-holding corn tortillas of the vanished Aztec empire influenced the Mexican table, which in turn drifted north with 16th-century Spanish settlement into the territory that would become Arizona. But the Anglos who rushed to exploit gold, silver, and copper deposits in the 19th century at hell-on-wheels camps like Tombstone, Bisbee, Wickenburg, and Oatman brought with them a distinctive Southern taste: bacon, gravy, cornbread, peaches.

The Arizona “restaurants” founded in the 19th century were little more than crude mining-camp mess halls, where genteel dress and table manners were distant abstractions.Not until 1973 did an Arizona restaurant win four stars from the Mobil Travel Guide: Tucson’s over-the-top Tack Room, which served haute cuisine with rhinestone cowboy flair

tweet this

“With an appetite as big as all outdoors, the Southwest eats with gusto. Its taste was early shaped by the sparseness of scrub country, the ‘isolateness’ of mountain and desert,” noted the author of a 1930s guidebook to the region, produced by the federal Works Progress Administration. “The lack of formality that has long characterized its table manners is of pioneer stock, induced by hard living. Of the countless hardships borne in the settlement of this vast region, lack of human companionship was alone insufferable. Eating without formality, then, could satisfy this craving for company better.”

Indeed, not until 1973 did an Arizona restaurant win four stars from the Mobil Travel Guide: Tucson’s over-the-top Tack Room, which served haute cuisine with rhinestone cowboy flair.

But things have changed drastically since then. There are now approximately 8,500 restaurants in this state that ring up a total $12 billion in sales each year, according to the Arizona Restaurant Association. More new establishments come in every week, from the deep-fried sports bars to the tablecloth-and-candles places.

Tucson writer Gregory McNamee, the author of the forthcoming book Tortillas, Tiswin, and T-Bones: A Food History of the Southwest (from which the preceding WPA quote was taken), said that he was recently driving past Tag’s diner in the time-forgotten cotton town of Coolidge when he fell into a reverie about the recent gastronomic history of the state.

“You can now live in Coolidge, that is to say, and with a little effort have as many food choices as a New Yorker or an Angeleno,” he wrote in an email. “Downtown Phoenix and its suburbs are jammed with excellent restaurants, while Tucson, named by UNESCO as a City of Gastronomy, has almost too many to choose from, with more restaurants opening than closing.”The restaurant must have some age to it: 20 years minimum. It must be a beloved institution within its city. It must somehow speak to a broader cultural theme within Arizona. And the food must be of passable quality.

tweet this

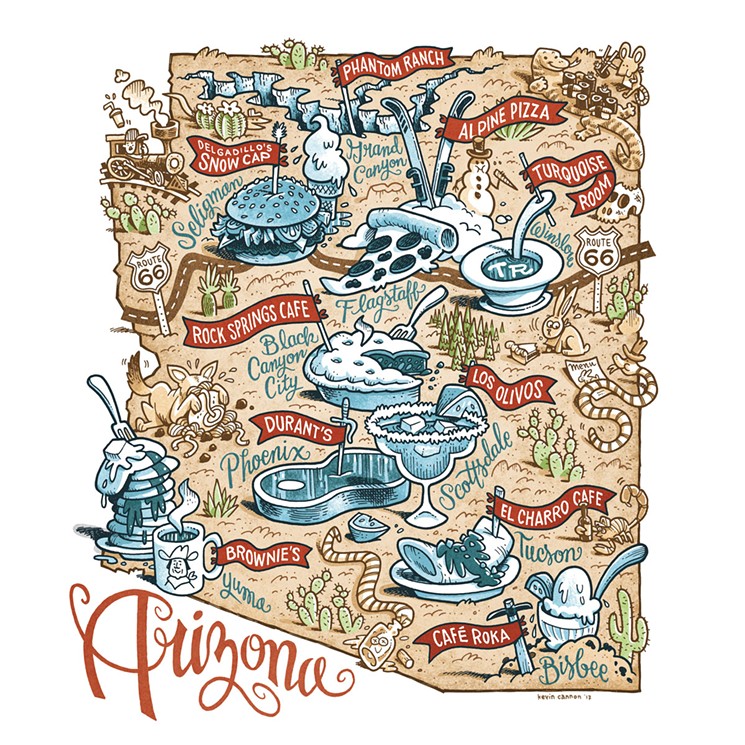

Amid all these terrific options, here are 10 of the most iconic restaurants of Arizona — those that have set a tone for all that have followed. Our selection criteria was highly subjective, and adhered only to a few general principles. The restaurant must have some age to it: 20 years minimum. It must be a beloved institution within its city. It must somehow speak to a broader cultural theme within Arizona. And the food must be of passable quality.

This last bit is important, because this certainly isn’t a list of the “Best Restaurants of Arizona.” A truly great restaurant is about so much more than the food. One of the knocks on Manhattan’s famous celebrity-zoo Elaine’s was that the chicken Parmesan tasted like cardboard and the marinara like ketchup. But the customers kept coming, the good buzz didn’t stop, the name became synonymous with a certain side of New York, and the restaurant thereby earned its place in literature. Dining there felt like being a part of something larger.

This is possible in Arizona, too.

Readers might not agree with all these choices. They will feel we have ignored gems and elevated greasepits. We made ourselves stop at 10, but there were several close calls: The Stockyards in Phoenix, built by Edward Tovrea next to what used to be the world’s biggest cattle feed lot; The Asylum in Jerome, tucked inside a former hospital and boasting unforgettable views of the Verde Valley; and The Peacock Room at the Hassayampa Inn in Prescott, a rehabilitated Art Deco restaurant in a 1927 hotel close by Whiskey Row.

As every restaurant owner knows, there is no such thing as pleasing every discerning customer. But an essential element of dining out is the conversation, the evaluation, and even the argument over cognac and ice cream. Bon appetit!

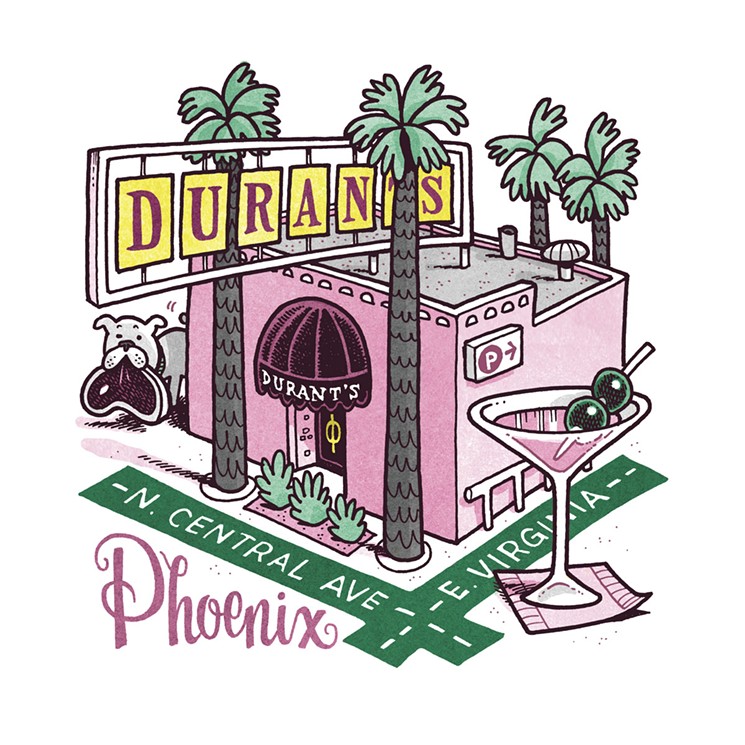

Durant’s

2611 North Central Avenue

602-264-5967

From the vermillion bordello-style wallpaper to the crackly leather banquettes, the efficient red tuxedos of the wait staff, the just-right darkness that gently smothers the angry sun just inches inside the door, and the stiff cocktails, buttery steaks and hard rolls, this place growls with atmosphere. Since 1950, when Jack Durant, a former pit boss at Bugsy Siegel’s Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas, opened his windowless palace of intrigue on Central Avenue, the restaurant has lain porterhouse steaks and dry martinis before Arizona’s power class. Durant died in 1987, but his spirit still infects the place. He once called his own restaurant “the finest eating and drinking establishment in the world,” and today’s customer is not inclined to disagree. Former columnist Jon Talton of the Arizona Republic made it his regular hangout and occasional inspiration.

“Durant’s has rich history — you walk in the back door through the kitchen like a made man — and everybody who was anybody could be found having lunch or dinner, from governors to Charlie Keating,” he wrote. “On a hot day, the darkness inside was a balm. And the red banquettes took us back to the 1950s.”

Rock Springs Café

35900 Old Black Canyon Highway, Black Canyon City

623-374-5794

Location counts for a lot, and Ben Warner knew this spot was a winner. It had a natural watering hole used for refreshing horses on the trip from Phoenix to Prescott, and Warner discovered that he could make a lot of money selling gasoline and bootleg liquor to early automobile travelers in the 1920s. The highway planners of the Eisenhower era also smiled on Rock Springs when they located Exit 242 of Interstate 17 not far from the edge of the parking lot of Ben Warner’s 1924 general store and hotel.

Though the interior is a little dingy, the quality and variety of pies make Rock Springs Café a memorable stop. The Rock has its die-hard fans who make it a regular part of their Flagstaff journeys, and also its critics, who fault the crust for its lack of flavor and some of the fillings for a suspiciously frozen-tasting pedigree. But they sling an estimated 80,000 pies a year to the hungry public, along with cowboyed-up staples like Two-Gun Chili and ranchhouse pork cutlets. Volume counts almost as much as a convenient freeway exit. So does history, as 1924 might as well be the Pleistocene era when it comes to Arizona restaurants still doing business.

Alpine Pizza

7 North Leroux Street, Flagstaff

928-779-4109

When Danny Rich was hired to run the ski patrol over at Arizona Snowbowl, that prepared the way for one of the West’s truly great outdoorsy hangouts. Rich’s brother opened Alpine Pizza in 1973 with two partners from Chicago, and the fast-talking, fast-moving Rich — a graduate of NAU and the Thunderbird School of Management — keeps the tradition alive with the same original recipes and the sportsman’s bric-a-brac adorning the walls. Look for the TQM Sandwich on the menu, for it contains a sardonic joke in addition to the peppers and mozzarella. The initials are that of an old girlfriend of Danny’s who happened to have a lot of money; she donated $25,000 to Alpine Pizza with the sole proviso that he name a dish for her. When he found out she had been seeing somebody else on his watch, he made her namesake sandwich big enough to feed two. But don’t feel too sorry for him. Photos of champion rock-climber Scott Baxter — a personal friend of Rich — hang on the walls, even though Rich said he stole Baxter’s girlfriend while the latter was off fighting in Vietnam.

In addition to the river guides, ski bums, red rock hounds, and other fleece-covered locals who make the place an après-adventure tradition, look for the wooden booths tattooed with generations of carved-in names. Recently, a 15-year-old girl tracked down the names of her parents, who had met there on their first date, and put her own beside them — the eventual outcome of that union. Rich is nearing 70 but still talks as fast as he skis. “I don’t know what old is in Flagstaff,” he says, complaining only that the messages people have written and carved on his walls and booth have declined since the halcyon literary days of the 1970s. “People who worked for me used to have master’s degrees in English, and what they wrote meant something. Now it’s all just babbling garbage.”

Los Olivos

7328 East Second Street, Scottsdale

480-946-2256

While it may seem that Old Town Scottsdale has been hopelessly mired in faux-Western schlock and kitsch since the days of the Hohokam, it was once a fairly average rural crossroads featuring a grove of olive trees planted by former U.S. Army chaplain Winfield Scott.

All the overpriced junkola began its invasion in 1951 under the watch of gas jockey-turned-mayor Malcolm White, and the more vulgar nightclubs began their own infestation in the 1990s, but an element of a more innocent time survives: Los Olivos Mexican Patio, founded next to a metal shop and named for Scott’s olive trees by the immigrant Corral family — one of the first Mexican families in town — who came up from Sonora to farm cotton. If you’re looking for the classic elements of Yanqui Mexican, you will find them here in generous quantities: chips and salsa, rocks-and-salt margaritas with triple sec, albondigas soup, combo platters with rice and beans. You’ll also have the pleasure of participating in a ritual dining experience known by a vanishing breed of longtime Arizonans.

Brownie’s

1145 South Fourth Avenue, Yuma

928-783-7911

Yuma sits in an actual desert, as well as a food desert. Its most visible strip of commerce along the Interstate 8 corridor is a chow dystopia of corporate-chain hell. The innards aren’t much better; the historic downtown — mostly wiped clean of the interesting architecture it once held — is anchored by two or three blah, locally owned eateries. This newspaper has been tough on Yuma in the past, referring to it as “an armpit” with a dead Main Street, but we will make partial amends here by drawing attention to Brownie’s on Fourth Avenue, a place where Yuma’s few tourists rarely venture but where the locals know to go for damn good diner food as well as an ear into local agrarian politics.

Owner Bobby Brooks used to be on the City Council and he’s friends with Sen. John McCain, so the plantocracy of Yuma knows how to find each other over coffee and big plates of locally made Kammann’s sausage. The Wrangler’s breakfast with three eggs and your choice of pressed meat is also a popular choice, as is the fish fry on Friday nights.

“It’s an old-fashioned, hometown, home-cooking restaurant,” says Linda Brooks, Bobby’s daughter. “Everything is made from scratch.” Brownie’s has been a presence in this town since 1946, when the owner — a dairy farmer named Mr. Brown — built an ice cream stand here and named it for his son, who was killed in World War II. Brooks took it over in 1977 and turned it into Yuma’s indispensible breakfast joint. We would be remiss not to note that Mexican food is conspicuously absent from the menu, just as Mexicans themselves are poorly represented in the local power structure — and the clientele at Brownie’s has a decidedly Anglo dominance, right down to the desert rats who look like they’ve just gotten off the nearby Camino del Diablo after a 40-day spell. But for a look and a taste of midcentury Arizona, as well as priceless overheard conversation at the ’50s-style counter, this is as good as it gets.

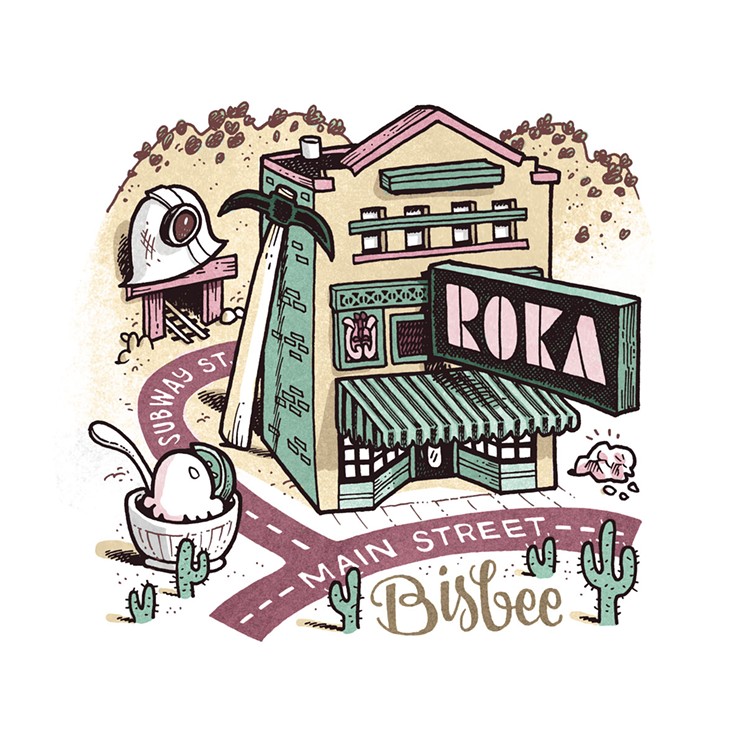

Café Roka

35 Main Street, Bisbee

520-432-5153

Tucked into its slopes and its gulches, the played-out copper village of Bisbee houses more interesting human beings than any other 2 square miles of Arizona, and possibly as many as the entire state put together. The Phelps Dodge mine went bust in 1973, leaving an astonishingly large pit in its center and a diorama of emptied cottages and charming Victorian homes that were gradually reoccupied by graying hippies, stand-up comedians, gays, lesbians, political activists, retired ornithologists, paroled former drug-dealers, reclusive millionaires, fashion models, turquoise bandits, and dozens of assorted polymaths who fit no recognizable category and wanted to live off the grid.

In 1993, two employees of Phoenix’s now-vanished Registry Resort — Rod Kass and Sally Holcomb — were looking for a place to open their own restaurant, and they picked a storefront in Tombstone Canyon that housed the Tavern Bar, a downmarket shot-and-beer establishment that nevertheless bore a mezzanine level and pressed-tin ceilings: relics of Bisbee’s elegant history as Southern Arizona’s richest town. Café Roka is open Wednesday through Sunday and only for dinner, but the whole gustatory experience earns it a spot on the list of icons, despite its young age. The fresh local ingredients; the vegetables grown on a farm in nearby Patagonia; the mandatory soup, salad, and lemon sorbet that come with every entree; the mixture of elegance and blue-jean informality; the ghosts of the past that seem to be hanging around the room; and the incomparable characters of the ongoing human comedy of Bisbee who gather at the wraparound bar to give each other a hard time make this a restaurant that stands as a delicious microcosm of its surroundings.

El Charro Cafe

311 North Court Avenue, Tucson

520-622-1922

The irony: America’s oldest operating family Mexican restaurant was founded not by a Mexican national but by the daughter of French immigrants. Monica Flin, whose father Jules was a stonemason who helped to build the nearby St. Augustine Cathedral, learned Spanish, married a Mexican man, and moved away, but returned to Tucson in 1922 after a divorce to open a restaurant that relied on a bit of leveraged creativity to help it squeak by. During lean times, she would sometimes take an order, run over to a grocery to get ingredients on credit, rush back and cook the meal, then quietly pay off the grocer with the customer’s money.

El Charro — named for a particular type of spangled horseman — also claims to be the birthplace of the chimichanga, that deep-fried burrito whose origins remain disputed. Monica’s relatives always claimed that it got its name from a Spanish corruption of the word “thingamajig,” which came out of Monica’s mouth after she dropped a tortilla full of beef into hot oil, and then started to say a Spanish verb beginning with “ch-” that implies fornication (yes, that one). Other signature dishes include the caldo de queso and the carne seca — spiced beef dried in a special cage on the roof. The restaurant now has two other locations in Tucson, and will soon open a prized spot in concourse B of the airport. But the flagship in the El Presidio neighborhood on Court Street — the old Flin home with its wide porch — is the place to come for the ambiance, for it feels like eating in an old friend’s living room. The neighborhood outside also happens to be the most European-feeling in the state — perfect for a post-repast stroll.

Delgadillo’s Snow Cap

301 AZ-66, Seligman

928-422-3291

For most of the 20th century, Route 66 was more than a paved connection to Los Angeles for the rest of the country. It was also a river of money for those who had the gumption and the startup money to open an eatery to lure the drivers off the Mother Road for a little while.

Juan Delgadillo was among the most imaginative of the Route 66 hucksters, and he built his drive-in from lumber salvaged from the nearby Santa Fe railroad yard — a fitting symbol, for the highway and all its colorful roadside barnacles were the replacements for the train route that connected northern Arizona’s linear vine of jerkwater towns. Delgadillo lavished his considerable sense of humor on the premises — a neon sign proclaimed “sorry, we’re open,” the menu featured “cheeseburger with cheese,” and a 1936 Chevy parked in the lot sported a Christmas tree sprouting from the back, while a phone booth outside housed a toilet. Delgadillo messed with his customers in other ways, by squirting “mustard” at them, which was actually yellow string from a bottle, or by first serving an absurdly miniature portion of an order. The comedy went on all day long, and although the puns and insults were too much for some grumps, families tended to remember the place and make repeat visits on their cross-country trips.

Seligman almost died after Interstate 40 routed cars from its downtown in 1978, but the Snow Cap — now patronized by foreign tourists as much as locals — preserves a specific time and culture of Arizona eating: the majestic era of the roadside ice cream cone and grilled delectables wrapped in white paper.

Turquoise Room

305 East Second Street, Winslow

928-289-2888

One of Arizona’s most sybaritic restaurants has its origin in an era of awful food: the time when Western train passengers were given flyspecked slop and told to like it. The Englishman Fred Harvey changed all that: He persuaded the Santa Fe Railroad to let him operate a chain of eateries along the tracks that treated customers like royalty, with haute cuisine to back it up: filet mignon, oysters, exceptional wine and gourmet coffee.

La Posada — “the resting place” — in Winslow was the last of the superlative Harvey Houses, designed by prolific Southwestern architect Mary Colter and built in 1930, and it survived only 27 years before the gradual decline of the passenger train forced it to close. The restoration artist Allen Affeldt saved it from oblivion 20 years ago and reopened the Turquoise Room restaurant, which routinely wins accolades from the international foodie press, and an attached hotel that retains Colter’s quirky touches like stained-glass windows, arched entryways, wrought-iron bars, and ashtrays shaped like jackrabbits. Insider tip: Make reservations for 7:30 p.m. because the westbound Southwest Chief passes by 20 minutes later, announcing itself with the rumble of a forgotten monarch and reminding the entire room full of diners the raison d’etre for the churro lamb and seared elk medallions on their plates.

Phantom Ranch Canteen

Corner of Colorado River and Bright Angel Creek, Grand Canyon

888-297-2757

A word of caution: Parking is a bit of a hassle at this establishment. The nearest lot is 7.5 miles away. You’ll have a walk descending through tens of millions of years of geological strata down to the bed of the Colorado River at the bottom of the Grand Canyon where Mary Colter — eight years before she got to work on La Posada — had designed a series of cabins and bunkhouses near the river’s junction with Bright Angel Creek. Flagstaff author Scott Thybony worked there in 1972 and goes back frequently to dine on food that’s been hauled in by mule train.

“The meals haven’t changed much,” he recalls. “Standard ranch fare. Last week, we had a hearty stew, with the emphasis on hearty, salad, and chocolate cake. No frills, and that works out fine since most people have left their frills behind by the time they get to Phantom. An industrial-strength air conditioner, which must have been salvaged from a meat locker, keeps the dining hall cool.” He adds, “One change since I worked there — the dining hall goes through as many set changes as a theater production. It begins the day as a coffee house, then transforms into a lunch room, a beer hall in the afternoon, then a dinning room before reverting back to a beer hall. They do their part to help people comply with the park service advice to drink plenty of fluids. Meals are family-style served on long tables. Good food, hard-working staff, set in the most spectacular surroundings anywhere.”

Careful about overeating if you have no room or campsite reservation, for it’s a long slog back to the car — at least six hours, even for those in top condition. But you can brag about having dined at Arizona’s most remote restaurant, and one of its icons.