Madison Haynie

Audio By Carbonatix

“Cool name — Phoenix,” Hozier told a packed house at Talking Stick Resort Amphitheatre on Tuesday night. “Pretty awesome to have a place named after a mythical bird that can’t die.”

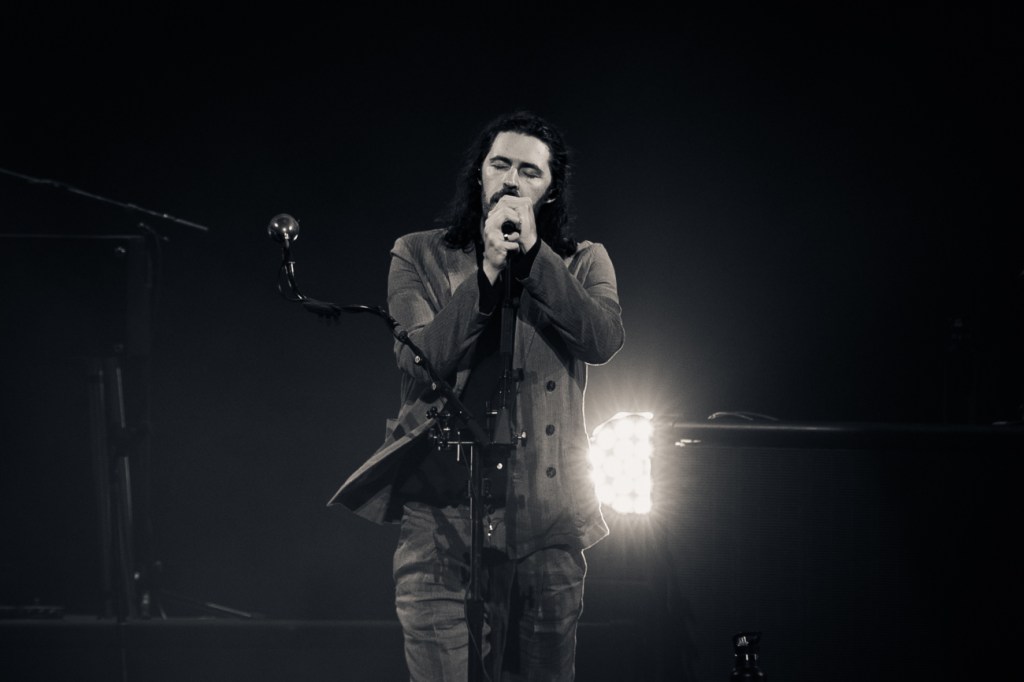

Few 35-year-olds anywhere have the bearing of Andrew Hozier-Byrne as he winds down his Unreal Unearth: Unending North American tour. He never looked tired, exactly, but could be forgiven for thinking he looks great for 50. On stage Tuesday, he let his long dark hair rest on his shoulders, as well as in a mini-bun; he wore a grey suit over a black button-up shirt; and in two hours of roaring like a furnace before 20,000 people, he never modified his outfit despite what, for him, a native of small-town coastal Ireland, were punitive temperatures.

“It’s a warm one,” he said after crashing a tambourine against his chest as he sang “Nobody’s Soldier,” the fourth number of a 22-song set. “It’s a spicy one. Not gonna lie.”

A woman near me sort of yell-muttered back to him: “Not really!” Reader, it was a blissful 80 degrees outside, and a strong breeze swooshed around beneath the amphitheater’s canopy, as soft a night as the Valley has enjoyed since April. Someone else added, with a hint of thirst: “Take off your jacket!”

This year, make your gift count –

Invest in local news that matters.

Our work is funded by readers like you who make voluntary gifts because they value our work and want to see it continue. Make a contribution today to help us reach our $30,000 goal!

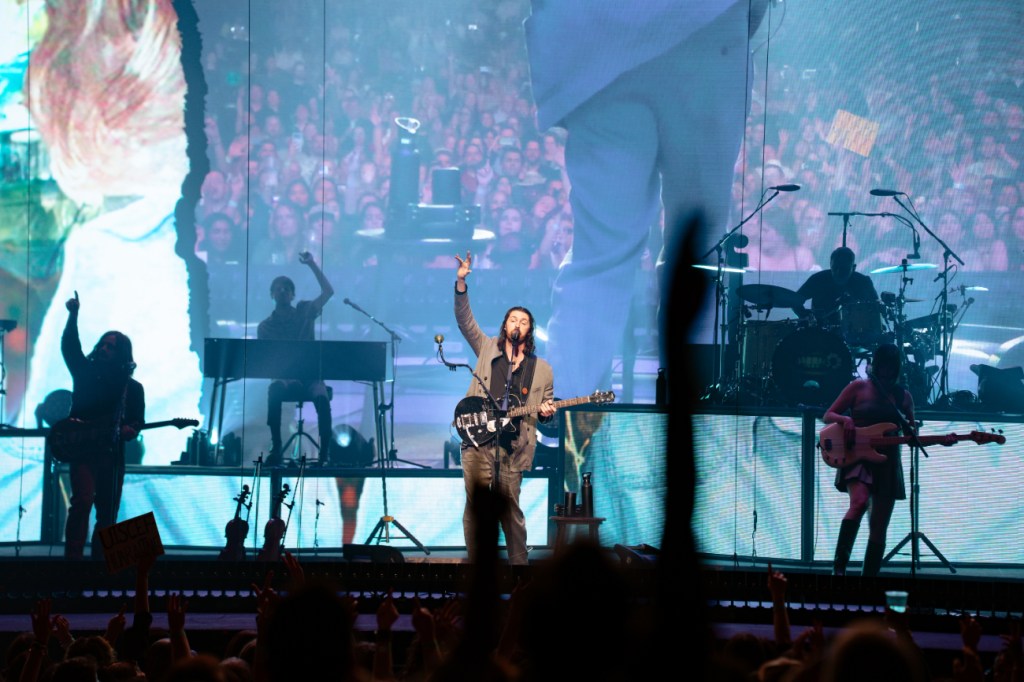

And yet, he never did. He stayed in the full suit as he delivered a steady parade of bangers and the biggest of his hits, crescendoing into such a delirious final half-hour that felt like an encore: a yearning “Francesca,” a bass-forward rendering of last year’s “Too Sweet” — his first U.S. No. 1 hit, the sneaks-up-on-you “Someone New,” a long walk through “Almost (Sweet Music)” that passed solos to six of his 10 backing musicians, a goosebumps-on-goosebumps changeup with “Movement,” and then the indelible “Take Me to Church.”

No one can deny that Hozier has a stunning voice, but on this, his most iconic track, he stretches it to the edge of his relatively modest range, and in no single song is it clearer why he summons such a robust ensemble of musicians to back him. Everyone on stage sang; the crowd sang; thousands of people swayed their bare arms churchily without anyone on stage prompting them; and the depth and breadth of his AAAAAAAaaaaaMEN! rippled through the grounds like an eruption.

By that hour, our brains had been melted, or at least tempered, by a dynamic visual set that projected elaborate environments across six square, wire screens that slid up and down above the stage. During “Dinner & Diatribes” (“That’s the kind of lovvvvvvvve / I’ve been dreaming oooooooof …”) water appeared to spill and splash, an immersive rainfall. On “Eat Your Young,” a tour of Dante’s third circle of hell — “Skinnin’ the children for a war drum / Puttin’ food on the table, sellin’ guns and bombs” — a mammoth projection tallied such festive statistics as the number of homeless people in the United States, the world’s total defense budget, the oceanic wealth of the world’s richest few people, and the steady, nauseating climb of Lockheed Martin’s stock price this century. The “amen” was a highlight of his set, but this capitalism calculus was the true hallelujah moment.

You’ll rarely see another artist more at ease sharing the burden of creating this swell of emotion. He introduced everyone on stage not once, but twice, the second time at a quarter til 11, when the crowd was somehow even more energetic than they were at 9, dwelling for a full five minutes on his band — and then launching into a series of thanks for his crew and support staff that felt like the credits of a Pixar movie and which culminated with a full-band, full-audience rendition of “Happy Birthday” for his blushing head of security, whom Hozier waved onto the stage from the wings.

(Funnily, he also waited till these final bars to acknowledge his quite lovely opening act, a young Irish folk band called Amble. “You’re just the best fans in the world,” Amble lead singer Robbie Cunningham told the crowd as their set wound down. The Phoenix tour stop was to be Amble’s last opening for Hozier, and they were verklempt. “This,” Cunningham told the audience, “has been the greatest honor of our lives.”)

Madison Haynie

At other times during the set, during songs such as “To Someone From a Warm Climate,” a song about the poetic power of coldness and wetness in the Irish language that does not feature a guitar part for the front man, Hozier stuffed his hands in his pockets, or wandered with the mic and a single hand in a pocket, with a professorial nonchalance. He may grow his hair to his shoulders, but he seems bent on quiet reminders that an aspiring messiah he ain’t.

That balance — between ego and message, between main character syndrome and the acknowledgement that his name can overshadow the talent backing him up — is not an easy one for a star to strike, least of all for an artist as overtly yet slyly political as Hozier. Once “Take Me to Church” wrapped and the stage went dark, before anyone dared sit or scamper out to the parking lot, Hozier appeared on the concourse heading to a stage in the center of the audience, stripped to a guitar, a mic, and spotlights blazing across the sprawling lawn of fans. He was feeling the wear of the heat in the suit. “No wonder you named the town after a bird that catches fire,” he told the crowd. He thanked people for buying tickets and coming out, because spending that kind of money is no small thing these days.

Then he launched into the stripped-down “Cherry Wine” (“Her eyes and words are so icy/Oh but she burns /Like rum on the fire” …) as hundreds of phone flashlights awoke and swayed over the field like fireflies. He followed that with “Unknown / Nth,” a lullaby with deceptively metal lyrics (“You know the distance never made a difference to me/I swam a lake of fire, I’d have walked across the floor of any sea”). He crooned that “so much of the living, love, is the being unknown,” the lament of every single, detached organism floating through the ether.

The softer, gentler numbers amounted to a feint. Hozier wants to tempt you into leaning in close, to feel the smoulder of his take on blue-eyed soul, but just as surely, he wants to pack that propulsive energy like an artillery shell. From the center audience, he rejoined his band on stage for a rendition of “Nina Cried Power” — a 2019 song that rides piano, organ and kick drum to a rapturous celebration of the civil rights movement — through which he called for peace and respect for people around the world, while cheering the canon of artists who have been carrying that fight for decades: union rights, reproductive rights, trans rights, a Palestinian state; Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Joan Baez, Mavis Staples, Nina Simone.

The sum of a huge band, the weight of history, gospel-grade joy, an 80-degree night of swirling breeze and 20,000 people cheering in unison against antisemitism and Islamophobia in the same breath — is this what it’s like to get religion?

This wasn’t church, but it seems that in a fair and just and Jesusly world, this is what church would be for, at least: bopping along to the choir, raising a middle finger to Lockheed Martin, and draping a lesbian pride flag beside the drum kit on the way off stage. This is why the mythical bird catches fire. This is why it never dies.

More pictures from Hozier’s Unreal Unearth: Unending North American tour

Madison Haynie

Madison Haynie

Madison Haynie