Stephen Lemons

Audio By Carbonatix

It may be way past time for some Maricopa County supervisors to eat a ginormous steaming plate of crow pie.

Back in July, during a community meeting about the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office’s efforts to follow a judge’s orders from the decade-old racial profiling suit Melendres v. Arpaio, several Republican officials lambasted the ongoing need to comply with them. Appearing at the quarterly meeting for the first time, GOP county supervisors Debbie Lesko and Thomas Galvin lamented the more than $350 million the suit is projected to cost taxpayers since 2013.

“This $350 million could have been used to hire more sheriff’s deputies,” Lesko said as Sheriff Jerry Sheridan and Robert Warshaw, the agency’s court-appointed monitor, looked on. Instead, she said, the money was being spent on “federal bureaucracy and red tape.” Playing the rabble-rouser, Galvin rose to address the assembled crowd, which included armed sheriff’s office supporters who had come from outside of the largely Hispanic West Valley area where the meeting was being held. He berated Warshaw, praised Sheridan and said the money allocated to the monitor each year should instead “be in the streets.”

If fiscal responsibility is the goal, though, Lesko and Galvin appear to have been barking up the wrong tree. Instead, as they say in slasher pics, the call was coming from inside the house.

On Wednesday, federal judge G. Murray Snow released a 93-page report from the monitor that claimed the sheriff’s office was improperly using money earmarked for compliance with Snow’s orders in the Melendres case. Instead of going directly toward efforts to police the Valley’s Latino communities without bias — and instead of going “in the streets” — tens of millions of dollars were spent on things like: parking; car washes; a new office for the sheriff’s Professional Standards Bureau; a golf cart; travel to Washington, D.C.; training for “mounted patrol;” research into watercraft; and the hiring of dozens of sergeants that the monitor’s accountants say did no work related to Melendres.

The bombshell report also recounts in excruciating detail how the sheriff’s office treated the Melendres fund like a piggy bank. MCSO improperly blamed the court for $163 million in purported compliance costs — or 72% of the $226 million that the county has spent on Melendres, excluding legal fees, from 2014 to 2024. As a result, both the county and the sheriff’s office may have violated state laws on spending limits to the tune of tens of millions of dollars.

The misspending and misallocation revealed by the audit span the administrations of four sheriffs: Joe Arpaio, Paul Penzone, Russ Skinner and now Sheridan, who was Arpaio’s chief deputy and was elected to office in November 2024. The makeup of the five-member Board of Supervisors has also changed several times between 2014 and 2024. The only person on the board now who was on it in 2014 is the board’s lone Democrat, Steve Gallardo, who has always been outgunned 4-to-1 by Republicans.

A day after the report was released, Galvin remained steadfast in his support of Sheridan, saying in a statement that the Board of Supervisors was reviewing Snow’s report with its legal counsel and would subsequently offer a reply to the court.

“The Board has confidence in MCSO’s budgeting team and will respond accordingly,” Galvin said.

Yet, the way the report tells it, the supervisors’ “confidence” in the sheriff’s office bean counters was severely misplaced — either intentionally or unintentionally.

Morgan Fischer

Robbing Peter

Snow ordered the financial review in September 2024, noting that the sheriff’s office had been identifying Melendres-related expenses simply as “operational costs” in annual reports submitted to the court by the agency. The sheriff’s office had failed “to provide support for the amounts attributed or an explanation of the underlying costs,” he wrote, giving the sheriff’s office 30 days to turn over the receipts to the monitor’s staff.

True to form, the sheriff’s office dragged its heels, finally “complying” in December with a massive data dump that involved, according to the report, “over 8,900 digital files” and “raw ledger data containing over 125,000 individual data entries.” If the monitor wanted to know where the money was going, its budget analysts would have to “sort through and organize” the morass.

Sort and organize they did, only to learn that the sheriff’s office had been conducting a spending spree for non-Melendres-related expenses, which county officials apparently rubber-stamped without checking to see if they comported with Snow’s orders. The county “does not monitor or audit whether Melendres funds are spent appropriately,” the report states, and this “permissive culture” allowed the sheriff’s office to piss away moolah and attribute the millions of dollars in outlays to Melendres.

A partial list of the sheriff’s office’s years-long splurge includes the following:

- $62.7 million in payroll costs for patrol positions unconnected to court compliance

- $32.9 million in payroll costs for non-patrol positions that were similarly unconnected

- $1.5 million in office renovations for a new, unneeded facility to house the agency’s Professional Standards Bureau

- $1.3 million for 42 vehicles not required to comply with Snow’s orders

- $490,000 in fuel costs

- $450,000 for internet services

- $309,400 for parking

- $43,948 for a “transit van” to ferry deputies to and from the field

- $11,805 for a golf cart so agency employees could ride back and forth between the PSB office and headquarters

- $7,699 for cable TV subscriptions from Cox Communications

- $3,259 on car washes

- $5,077 for travel to Washington, D.C., for “National Police Week”

- $1,261 to “research watercraft purchase and swift water rescue training”

- And, the pièce de résistance: $4,070 for “mounted patrol training and testing and travel to purchase possible mounted unit horses”

Which, given the circumstances, puts a new twist on the phrase “horse thief.”

Per the report, some 84% of the Melendres charges were for personnel, but many of these positions were not required by court order or necessary for compliance.

Part of Snow’s order required the sheriff’s office “to establish staffing that permits a supervisor to oversee no more than eight deputies, but in no event should a supervisor be responsible for more than ten persons,” with an 8-to-1 ratio being the target. Snow’s order was limited to deputies on patrol, but according to a sheriff’s office communique quoted by the report, “the County and the MCSO” decided to expand the standard to “all enforcement divisions,” greatly expanding the rate of hires.

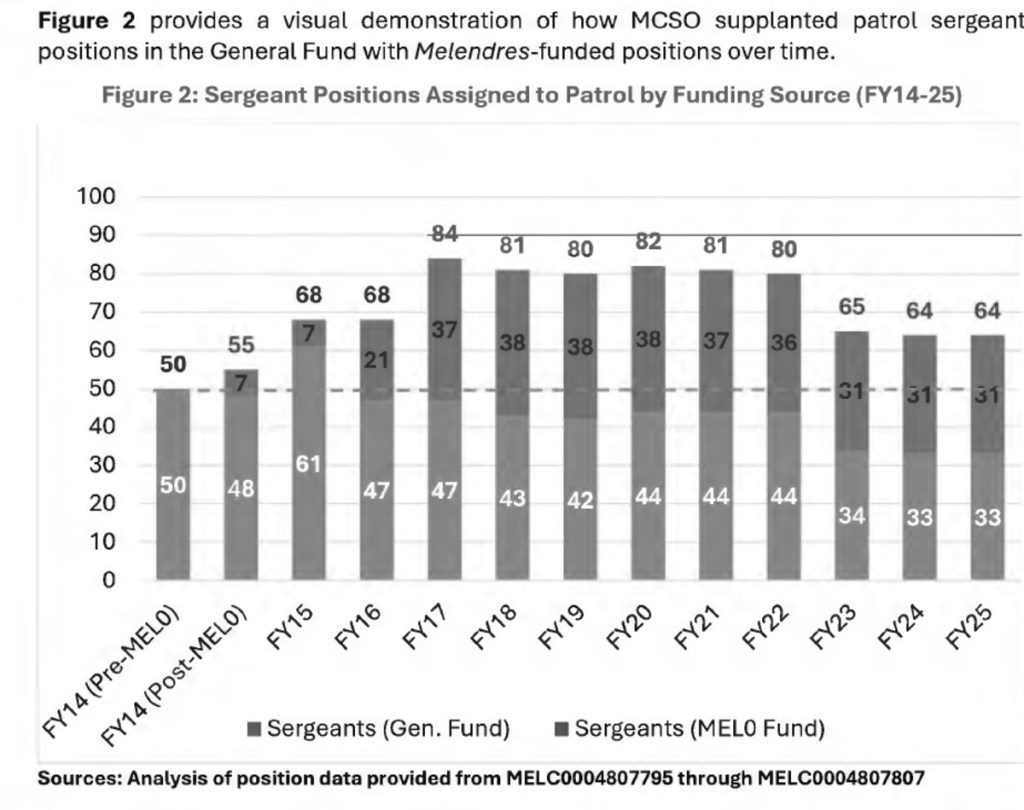

The report also contends that the sheriff’s office pulled a switcheroo when it came to the hiring of some sergeants, swapping out positions that should have been covered by the county with positions paid for with Melendres funds. The monitor believes such accounting tricks helped inflate the spending that the sheriff’s office was blaming on Melendres. Ultimately, auditors found that as many as 87 positions at the sheriff’s office were wrongfully attributed to Melendres.

Court documents

Another beef of the monitor’s: The sheriff’s office did not prorate expenditures that might overlap between Melendres compliance and the regular work of sheriff’s deputies.

“If a position is attributed to Melendres, it is considered a direct cost of Melendres, and all costs associated with that position are attributed to Melendres,” sheriff’s office officials are quoted as stating in the report.

This resulted in a “systematic overstatement” of Melendres costs because some of those positions — even by the sheriff’s office’s own admission — were only partially related to Melendres compliance. Goods and services were similarly assigned to the Melendres column, though Melendres compliance was but one element of their use. One example: $72,119 spent on rental lease costs for a Ricoh photocopier that “supports normal business operations unrelated to Melendres.”

So what? one might say. The county would have paid for this stuff one way or the other.

Not necessarily.

The report argues that these loosey-goosey practices allowed Maricopa County to exceed budget limits imposed by the Arizona Constitution. Complying with court orders is exempted from the spending cap, so the more charged to Melendres, the bigger the overall budget for the sheriff’s office.

For Fiscal Year 2022, “the County exceeded the State constitutional expenditure limit by over $13 million because MCSO improperly attributed inappropriate costs to the Melendres case and the County excluded them from the limit.” The report suggests this “pattern of misattribution” may have caused the county to speed past spending limits in other years.

“MCSO and Maricopa County had an incentive to allocate and overstate what should be regular operating costs to the Melendres Fund so that MCSO could bypass the State constitutional spending limit,” the report states, though it leaves open the question of whether this was “by design” or was simply the result of shoddy accounting practices.

Morgan Fischer

Picking nits

If the idea behind all the compliance cost pearl-clutching was to free the sheriff’s office from Snow’s supervision, it’s likely to backfire.

Sylvia Herrera, a community activist and member of the Community Advisory Board created by the court to assist with Melendres compliance, told Phoenix New Times that the board was the first to call for the kind of audit that Snow eventually ordered. Both the county and the sheriff’s office “should be held accountable for public overstatements” of Melendres’ costs, she said, and the lack of transparency and persistent misrepresentations by the sheriff’s office demonstrate that it “must continue to have court oversight.”

Victoria Lopez — the executive director of the ACLU of Arizona, which represents the plaintiffs in the Melendres case — said there should be hell to pay.

“The audit raises serious issues including possible violations of state law, which would need to be reviewed by state officials,” she told New Times via email. “Additional transparency and accountability are necessary for the public to fully understand the depth of the problems raised in the report.”

A spokesperson for Arizona Attorney General Kris Mayes, who would investigate violations of state law, declined to comment when asked what, if anything, she might do about the report’s allegations.

Sheridan, though, is nitpicking.

“We have found discrepancies within the Monitor’s budget analyst report, which we are continuing to review and will address in the future,” he said in a statement issued Thursday. “However, if we accept their report’s stated total expense of $62 million, it is unclear why the costs paid to the Monitor Team — totaling $34 million to-date (more than half of the reported expense) — and the legal expenses incurred over the past decade were excluded. These two significant and undisputed expenses were not included in the report.”

Sheridan seems to focus exclusively on the cost of non-Melendres-related positions, ignoring the other costs and his agency’s neglect in not prorating certain expenses. While he is correct that legal expenses are not included in the report — a point acknowledged both by Judge Snow and the monitor’s report — he forgets a salient fact: The sheriff’s office lost the suit in federal court, making it liable for the plaintiffs’ legal expenses.

According to data provided by the county, from 2008 through the budget for Fiscal Year 2026, total legal costs for the Melendres case top $24.6 million, with the plaintiffs accounting for around $13.6 million of the total and the defense — i.e., the county — accounting for more than $11 million. Sheridan’s total for expenses paid for the monitor’s services for 12 years seems a fairly accurate estimate, but that figure would be far smaller if Sheridan’s agency had complied with Snow’s order from jump.

And it’s certainly dwarfed by the sheriff’s office’s own profligacy.

Morgan Fischer

Graves’ ghost

Melendres has become such a convenient punching bag for Republican politicos that the truth rarely gets in the way of absurd rhetoric.

Congressman and gubernatorial wannabe Andy Biggs recently begged U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi to “finally resolve the case and end this prolonged federal overreach,” seemingly ignoring the fact that Bondi has no such authority. Melendres is not a consent decree brought on by the Department of Justice, but a lawsuit brought in 2007 on behalf of all Latino drivers and passengers who might be stopped or detained by sheriff’s office deputies.

In 2013, Snow ruled that the minions of then-Sheriff Joe Arpaio had improperly used race and ethnicity to pull over automobiles for the flimsiest of reasons so they could question Latinos about their immigration status. Snow found that Arpaio’s agency was in violation of the Constitution’s prohibition against unreasonable search and seizure, as enshrined in the 4th and 14th Amendments.

Later, Snow ordered a litany of reforms to be enacted by the sheriff’s office, which Arpaio and his staff defied, earning Arpaio a criminal contempt of court conviction for which he was eventually pardoned by President Donald Trump. A handful of Arpaio’s underlings — including Sheridan, his chief deputy at the time — caught civil contempt citations. Sheridan’s untruthful answers to an outside investigation of the matter landed him on the county’s Brady list of untrustworthy cops.

Snow appointed Warshaw as his monitor to oversee the sheriff’s office’s enactment of Snow’s reforms. But the sheriff’s office — under multiple sheriffs — has had a history of institutional intransigence, sometimes slow-walking requests, sometimes exhibiting outright defiance. As a result, 12 years after Snow’s findings, the sheriff’s office is still not in full compliance with all of Snow’s orders, which it must be for three years before the court’s oversight ends.

Melendres’ critics have used its alleged $350 million price tag — which the monitor’s report belies — to insist that the court is out of control and its power over the sheriff’s office must end. They also cite the 18-year length of the case to argue for its cessation.

But there is local precedent for Melendres, specifically with a civil rights case known as Graves v. Hill. That case was filed in 1977 over conditions in the county jails and did not end for four decades. In 2019, federal Judge Neil Wake finally declared the sheriff’s office to be in compliance with his orders in the case.

As for the Melendres case, both the monitor and Snow have said that the sheriff’s office has made considerable progress in meeting the goals Snow set for it, so it seems unlikely that Melendres will take a Graves-like 42 years to resolve. But as Maricopa County taxpayers have learned the hard way, bigotry, especially when practiced by law enforcement, can be expensive.

Fortunately, with a yearly budget of around $4 billion, Maricopa County can afford to address the sheriff’s office’s legacy of racism. Even by the county’s allegedly inflated accounting, spending an average of $29 million a year on Melendres out of a $4 billion annual budget represents less than 1% of the county’s yearly costs. Over the same time frame, the county’s yearly budgets total nearly $40 billion. Melendres has been a drop in the county’s colossal bucket o’ cash.

Strip out all the unrelated expenses the sheriff’s office has billed to the cause of “stop being racist” — the golf carts and horse trainings and cable TV — and the fraction gets whittled down further. Though likely not enough to quiet the phony cavils of naysayers such as Galvin and Lesko.

This story is part of the Arizona Watchdog Project, a yearlong reporting effort led by New Times and supported by the Trace Foundation, in partnership with Deep South Today.