Illustration by Eric Torres

Audio By Carbonatix

Inside a health clinic at the base of a craggy mountain on the Arizona-Utah border, May Keate’s phones won’t stop ringing. If the landline isn’t interrupting her, she’s silencing her cell phone to continue a conversation. It’s been like this for the past two months at Hometown Wellness, where Keate is the billing manager. The clinic’s two physicians and staffers have been kept busy responding to a growing, border-spanning outbreak of measles, one of the most infectious diseases known to man.

Hometown Wellness sits in the scenic southern Utah town of Hildale, which hugs the border across from the northern Arizona hamlet of Colorado City. But few who live there make such a distinction. All of this is Short Creek — or “the crick,” if you live there. Fewer than 5,000 people do, many of them treating the twin municipalities as a single entity. The Arizona side even follows Utah’s time zone.

The border line doesn’t mean much to Creekers, as residents call themselves. It certainly doesn’t mean anything to measles. Since early August, Short Creek has been besieged by measles cases. As of Oct. 15, there have been 73 positive measles cases in Arizona’s Mohave County, almost all of them traced to Colorado City. Another 41 cases have been traced to Hildale on the Utah side, spreading into St. George and Cedar City, both roughly an hour away. Combined with four cases in Arizona’s Navajo County — which, unlike the Colorado City’s numbers, never grew — the Short Creek outbreak is now the biggest Arizona has seen since 1991.

It’s been keeping Short Creek’s health workers busy and Keate’s phones buzzing. Her clinic has seen patients of all ages — from children and teenagers to full-grown men — who are in the throes of the disease. First comes the head cold, then a runny nose and fever that can spike to 106 degrees. White spots appear in the mouth and a red rash covers the face, traveling down the rest of the body. Measles weakens the immune system, and Keate says “tons” of patients have contracted pneumonia, forcing them to seek treatment at bigger facilities at least a half-hour away. Luckily, no one has died from measles, at least yet.

“I get people who have 15 to 20 kids in their family, calling and saying, ‘What should we do? We’re all sick,’” the 55-year-old Keate says, hunched over and exhausted in her cramped office off the clinic’s only hallway.

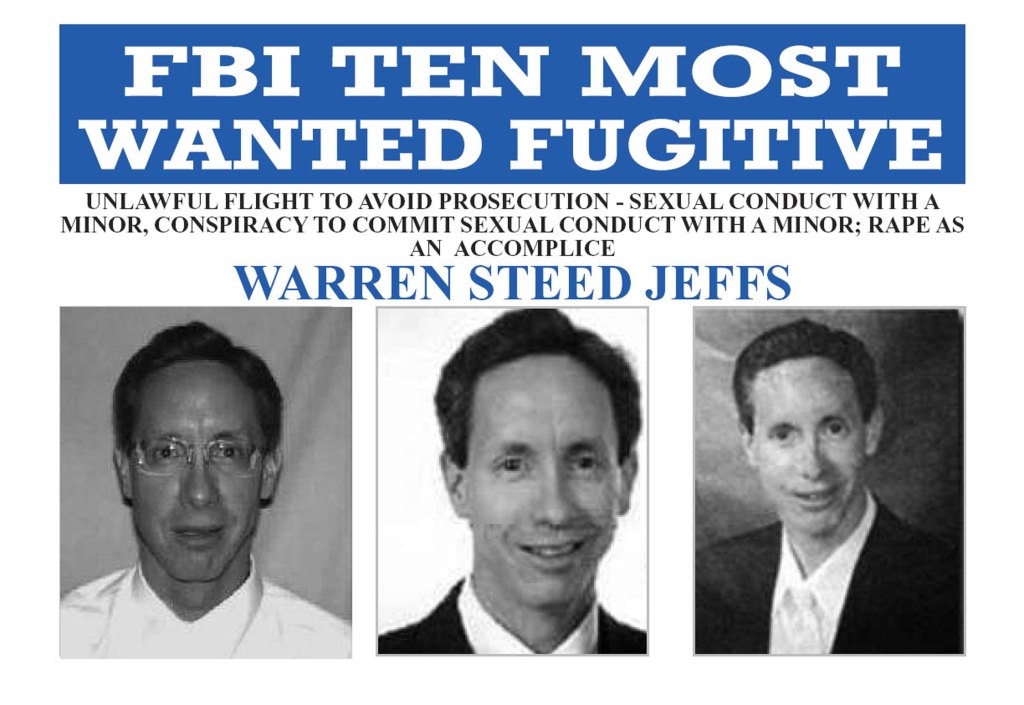

Fifteen to 20 kids is quite the passel of children, a sign that Short Creek isn’t like most places. It’s no coincidence that measles, a disease considered eradicated in the U.S. in 2000, would spread here. For a century, Short Creek has been defined by its association with the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or FLDS, a polygamous offshoot of the modern Mormon church. In the early 2000s, Short Creek became infamous because of FLDS leader and “prophet” Warren Jeffs, who exercised cult-like control over church members and married an estimated 78 women — many underage, and one as young as 12. Before he was arrested in Nevada in 2006, Jeffs occupied a spot on the FBI’s most-wanted list.

The 69-year-old Jeffs has been serving a prison term in Texas since 2011, and much has changed in Short Creek without him. Many who left the church and Short Creek to escape Jeffs — including Keate — returned to the area once he was behind bars. Short Creek now has more former FLDS members, or apostates, than current members. The area is still full of dirt roads, extra-large unfinished homes and occasional livestock, as it was during Jeffs’ reign. Meanwhile townhouses, modern new builds, breweries, glamping sites and drive-thru coffee shops have also popped up. With each passing day, the shadow of Warren Jeffs fades ever so slightly.

But Jeffs’ influence is far from gone. It lingers in the repurposed church buildings, including Jeffs’ former home. You can see it in the large families, many of whom share the same last name. And, as measles has thoroughly exposed, it’s there in Short Creek’s low vaccination rates — a result of Jeffs’ distrust of outside medical professionals and, in turn, Creekers’ post-Jeffs suspicion of anyone trying to exert control over their lives. Nearly everyone who has tested positive for measles was unvaccinated. Even in a small town, there’s plenty of territory for measles to conquer. Right now, the spread of the disease doesn’t figure to slow until either “everybody’s got it or everybody’s immunized,” Keate said.

In a town that has labored to move past the dark days of Warren Jeffs, leave it to measles to bring the not-so-distant past crashing, rash-covered and running a fever, into the present.

Joern Gerdts/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

‘Hunting rabbits with an elephant gun’

The history of Short Creek, and its residents’ wariness of the government, goes back to 1887 — decades before Colorado City was founded.

That year, in an effort to crack down on the Mormon practice of plural marriage, Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act, which disincorporated the Mormon church and seized its assets. Three years later, then-LDS President Wilford Woodruff signed a manifesto eliminating the practice of plural marriage within the Mormon church. “The end of plural marriage required great faith and sometimes complicated, painful — and intensely personal — decisions on the part of individual members and Church leaders,” reads the LDS church website. For some, that decision meant abandoning the church, and landing in Short Creek.

Mormon fundamentalist sects, including the FLDS, believed the church “abandoned one of the religion’s most crucial theological tenets for the sake of political expediency by doing away with polygamy,” author Jon Krakauer wrote in his book “Under the Banner of Heaven.” “These present-day polygamists therefore consider themselves to be the keepers of the flame — the only true and righteous Mormons.” Colorado City was founded in 1913 by the Council of Friends, a fundamentalist Mormon group, and Short Creek sprang to life in the 1920s as polygamist members moved to the area. If the law came, residents could jump from one side of the Arizona-Utah border to the other to avoid arrest.

The law finally caught up in 1953, culminating in a raid that still reverberates in Short Creek today.

Morgan Fischer

Just before dawn on a July morning, more than 100 Arizona law enforcement agents descended into town in an effort by Arizona Gov. Howard Pyle to eliminate the practice of polygamy from the state. Tipped off about the raid, more than 400 FLDS residents met the agents with a religious hymn. Agents arrested and jailed the men in Kingman, while most of the women were sent away to Phoenix. More than 160 children from the polygamous families were taken away by law enforcement and placed into state custody, some to never return to their parents. Frank Pierson, a reporter for Life magazine who witnessed the raid, described the force brought down on Short Creek as being “like hunting rabbits with an elephant gun.”

The raid, and the images of children being torn from their families, caused tremendous blowback for Pyle, who lost his reelection bid a year later. Its effects on Short Creek have been longer-lasting. One of the children taken by the state was the mother of Howard Ream, who now serves as Colorado City’s first ex-FLDS mayor. Leaning back in his chair in a conference room at Colorado City’s small town hall, Ream calmly recounts how Arizona “incarcerated our moms.” In his late 50s, Ream was not alive for the raid, but he says it’s left deep scars and a “baseline fear” in Short Creek families “that the government doesn’t have our best interest” at heart.

“When the government says, ‘Hi, we’re here from the government. We’re here to help you,’ people are skeptical,” Ream says.

After the public relations disaster of the 1953 raid, Short Creek remained unbothered for more than 50 years. In that time, the FLDS became the dominant fundamentalist group in the area. In 1998, Rulon Jeffs — the fifth FLDS president and “prophet” — claimed to have received a revelation that Salt Lake City would be destroyed during the 2002 Winter Olympics. He ordered all FLDS members to sell their homes, donate the money to the church’s trust, the United Effort Plan, and move to Short Creek. The population ballooned: Colorado City grew from 2,426 people in 1990 to 3,334 in 2000, a jump of 37%.

That same year he ordered FLDS members to Short Creek, Rulon Jeffs suffered a stroke. The reign of his infamous son, Warren Jeffs, began.

Morgan Fischer

Vaccinated ‘to a point’

It’s an early October evening on the Utah side of Short Creek, and the Water Canyon High School gym echoes with cheers and the sounds of a volleyball being smacked back and forth. Metal stairs clang as students run up steps, popcorn in hand, to hang with friends. Others sit by their teachers for help with math homework. It’s senior night, and four players are honored with flowers. The boyfriend of one surprises her by asking her to Saturday’s homecoming dance.

There’s little outward sign that school is in the midst of a measles outbreak.

Measles is almost assuredly here, though. According to the Utah Department of Health and Human Services, Water Canyon’s roughly 350 students could have been exposed to measles at the school in early September and again later in the month. Only 80% of students have been vaccinated against measles — 95% is required for herd immunity — meaning measles has ample room to spread. The volleyball game is happening while the school is still on measles symptom watch.

The school, which can be seen from the front door of the Hometown Wellness clinic, has been trying hard to keep sick or unvaccinated students home amid the outbreak. Some students have remained home for nearly three months. Before returning to school, students who contracted measles must wait 21 days from when the last person in their home tested positive before coming back. Many Short Creek homes have a lot of children, though, and some families are waiting only a week before sending their kids back to school. One of these positive cases was a boy dating the daughter of Hildale’s mayor, Donia Jessop. He got “really sick,” Jessop says, but “he’s doing good now.”

Other Short Creek schools are worse protected. Only 40% of students at Colorado City’s high school are vaccinated. At the area’s charter school, only 7.7% of students have received the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine. “There are a lot of people that don’t do immunizations,” Keate says of Short Creek residents. “At all.”

The outbreak has led more families to seek out the vaccine, but the attitude toward vaccination in Short Creek is generally ambivalent. Before the school year started, Keate took her 16-year-old son, who attends Water Canyon, to the Mohave County nursing station to receive his second dose of the MMR vaccine, and she’s “relieved” she did. Ruby Jessop, a waitress at the Blue Agave restaurant in Colorado City and a former FLDS member — there are a lot of Jessops in Short Creek — got her kids vaccinated “to a point,” but she isn’t “too terribly worried” about the outbreak.

“As a parent, you’re like, I’ve been through a lot. That’s why I have an immune system,” Ruby Jessop says. “I swallowed so much dirt. I drink from the tap. I bet I swallowed some tadpoles.”

Handout by Federal Bureau of Investigation via Getty Images

The rise and fall of Warren Jeffs

On a warm fall afternoon in 2002, more than 5,000 FLDS members filed into Short Creek’s large meeting house. Men wore their Sunday best. Women and girls donned long pastel dresses and wore their hair in immaculate braids that flowed down to their hips. They were there for the funeral of Rulon Jeffs, known affectionately among church members as “Uncle Rulon.” It also marked an effective coronation for Warren Jeffs.

Warren Jeffs had “long functioned as prophet in anything but name,” as Krakauer wrote in his book, but now he was getting ready to officially take over the title. A thin man at 6-foot-3, with a slender face framed by wide-brimmed glasses and bulging Adam’s apple, Jeffs had “no love for the people,” one of his older siblings told Krakauer. “His method for controlling them is to inspire fear and dread. My brother preaches that you must be perfect in your obedience. You must have the spirit 24 hours a day, seven days a week, or you’ll be cut off and go to hell.”

Warren imposed that obedience harshly and quickly. He ordered all FLDS children to be taken out of public school in Short Creek. Women were required to ditch their denim and patterned clothing and wear only long dresses with long underwear underneath. Jeffs declared that FLDS members weren’t allowed to wear red — the color belonged to Jesus, he said — watch gentile books or movies or speak to anyone who had left the church.

Some didn’t leave by choice. Jeffs broke up families by kicking out fathers from the community and giving their wives and children to another family. In 2004, he stood up in the meeting house and publicly expelled 21 of the community’s highest-ranking men, labeling them “master deceivers.” The same fate often befell other young men in the community. When men can marry scores of wives, “too many boys” can sometimes be a problem.

Jeffs exerted a similar control over the health of his followers. He eliminated in-town health care clinics and forbade vaccines. He stopped sending members of the community to college, meaning no Creekers returned with medical degrees. If someone got sick, Jeffs insisted it was because they’d let in a “bad spirit,” says Short Creek resident Briell Decker, who was formerly Jeffs’ 65th wife. Members were ordered to not vaccinate their children. The only way for Creekers to get health care and vaccines was to go against the word of the prophet and leave Short Creek.

Morgan Fischer

Few risked Jeffs’ ire by doing so, Decker says, at least over vaccines. Natural or herbal medicine has long been preferred and practiced by many members of the community, so people “just accepted” the order to stop vaccinating their children.

“Maybe it’s another power-control thing,” says Keate, who heeded Jeffs’ instructions about vaccines at the time. “I don’t know why, but he just said not to do it anymore.”

Violating a much more serious taboo led to Jeffs’ downfall. Jeffs arranged the marriage of many young girls in Short Creek to older members of the church, adding several of them to his own harem. Ruby Jessop was 14 in 2001 when she learned that Jeffs had arranged for her to marry her 20-year-old second cousin. Jeffs and other church leaders drove her and another 14-year-old bride, Elissa Wall, to a motel in Caliente, Nevada, to get married. A year later, Jessop tried to run away, but was brought back. By the time she was 24, she and her husband had six kids together, and Jessop has said none of those pregnancies were her choice. In December 2012, she left in the middle of the night and moved to Phoenix, filing for divorce that same month.

Wall left much earlier, fleeing the church as a 17-year-old after being repeatedly forced to have sex with her husband. She’d soon become a key witness in the effort to bring Jeffs to justice for his crimes. In 2005, an Arizona grand jury indicted Jeffs, who’d fathered children with at least two underage girls he’d taken as wives, for sexual conduct with a minor. The next year, Utah authorities charged Jeffs with being an accomplice to rape. Charges in Texas, for the rape of two minors, would follow in 2008.

In 2005, with authorities closing in on him, Jeffs went on the run. He landed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list, sharing prominent placement with Osama Bin Laden. In 2006, a Nevada state trooper arrested Jeffs after a traffic stop, and he hasn’t enjoyed a free day since. Utah convicted Jeffs on two felony charges in 2007, though the Utah Supreme Court later ordered a new trial after finding that the judge gave improper instructions to the jury. The Arizona charges were dismissed with prejudice — witnesses shirked at testifying, and Jeffs had already been in prison longer than his likely sentence would have required — but Jeffs was extradited to Texas, where he’d begun to bring his “elite” followers years earlier.

In 2011, Texas prosecutors convicted Jeffs on two counts of sexual assault of a child, for the rape of 12- and 15-year-old “wives.” A judge sentenced him to life in a Texas prison. Despite that, he will be eligible for parole in 2038.

Morgan Fischer

‘Measles is preventable’

Ashley Garcia sits at a wooden picnic table outside Short Creek Cottage in Colorado City, located off the main drag of Central Street. Inside the small pink building is a boutique where both FLDS and ex-FLDS women sell crafts and homemade goods. Garcia is the executive director of Voices for Dignity, an organization in town that provides support to FLDS women and other community members. It also runs the boutique.

Unlike most residents, Garcia isn’t FLDS or even ex-FLDS. She first moved to the area eight years ago when the right-wing Dream City Church in Phoenix transferred her to work at the satellite Short Creek Dream Center, which is now housed in Jeffs’ old home. She returned south after a short stint, but moved back a year ago, drawn by a love of helping others and the beautiful mountain landscapes.

Another thing also pulled at Garcia, the same thing that has made Short Creek vulnerable to measles: the area’s affinity for homeopathic and natural medicine, and its skepticism of established medical science. As much as Short Creek tries to outgrow Warren Jeffs, its resistance to traditional medicine — a trait that has become more mainstream across the country in light of Robert F. Kennedy Jr’s. science-averse Make America Healthy Again movement — has drawn new people to it.

“I was an herbalist before I moved here, so I thought I was special, until I moved here,” Garcia says. “I know nothing, absolutely nothing in comparison.”

Garcia doesn’t believe in antibiotics and prefers homeopaths to treat illnesses. She waited to vaccinate her children, doing her own research, picking and choosing which immunizations to give her kids, and spacing out their shots. Her oldest son, Ryler, didn’t get his MMR shots until he was about 7 years old, she says. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that kids receive their first measles dose when they are between 12 and 15 months old.

In Short Creek, many share Garcia’s beliefs about health care. Amid the measles outbreak, Facebook commenters have questioned whether measles is actually that bad and have invited sick families over to their homes. Others in the community hold to the belief that vaccines are “proven to increase disabilities,” says Ream, the Colorado City mayor. Ream counts himself among those who share that perspective. But like so many people in Short Creek, his views are nuanced: While he, too, waited until his kids were older to get them vaccinated, he steadfastly believes in the value of vaccines. “Just like anywhere, there are anti-vaxxers who will have none of it,” Ream says. That includes his own daughter, the mother of his three grandchildren, with whom he hasn’t discussed measles because “it wouldn’t be productive.”

Clinics like Hometown Wellness, where Garcia seeks care, have to adapt their offerings to the local mood. Garcia says the clinic dispenses a “really great mix” of natural medicine and pharmaceuticals, which makes residents more comfortable procuring treatment there. In the clinic’s waiting room, a glass case contains a host of natural options, including mushroom dietary supplements and super beet chewables. A sign from the Mohave County Department of Public Health reading “measles is preventable” hangs in the entrance hallway.

Patients cannot get vaccinated for measles at Hometown Wellness, though. The clinic stopped purchasing and providing doses of the MMR vaccine because so few patients asked to get them. The vaccines kept expiring, forcing the clinic to throw them out.

Like many in Short Creek, Garcia isn’t worried about the measles outbreak. A stomach virus that hit the community around the same time was “worse,” she says.

“It was awful,” she says of the stomach bug. “I feel like everybody had it.”

Morgan Fischer

A post-Warren Jeffs world

Donia Jessop left Short Creek in 2012 and swore she’d never go back.

When Jessop and her family left the church, Warren Jeffs was in prison but still very much running things in Short Creek. His brother and conduit, Lyle Jeffs, interviewed every community member to decide if they were worthy of joining Warren’s elite followers. Every member of the family had to be deemed worthy, otherwise “your whole family will be taken away from you and scattered,” Jessop says. In Jessop’s family, only her 9-year-old daughter was found to be “clean and pure.” Instead of following the imprisoned prophet’s command, Jessop’s entire family left the church and Short Creek.

“The thing that Warren Jeffs did is he ripped our foundation out from under us,” Jessop says. “Our families, our very identities.”

During this turbulent period, many left the church for similar reasons. Keate became a single mother and fought in court to get custody of several of her children, who had been placed with other FLDS families. Ruby Jessop did the same. Ream moved away and bought a home in Las Vegas. At Jeffs’ direction, Decker was imprisoned in her brother’s trailer until she jimmied open a window and escaped.

Meanwhile, those who stayed with the church began to be evicted from their homes. After Jeffs’ arrest, an accountant appointed by the state of Utah took control of the church’s trust, which owned nearly all of the property in town. To stay in their homes, FLDS families had to sign an occupancy agreement and pay $100 a month to cover the unpaid property taxes. It was meant to be a temporary measure to avoid displacement while the state untangled issues with the trust, but Jeffs told his followers to not sign or pay anything. From 2005 to 2015, the trust ordered evictions on roughly 200 homes. According to the podcast series “Unfinished Short Creek,” between 2,000 and 3,000 FLDS members may have been displaced. Many FLDS families moved elsewhere, some as close as Cedar City an hour north, some as far as Mexico or Canada.

There was now abundant real estate in Short Creek. Former FLDS members moved in and bought UEP homes for cheap. Just as they had left, slowly, apostates trickled back into Short Creek.

Three years after Donia Jessop’s family left for Santa Clara, Utah, her husband told her the mountains were calling him. He wanted to go back. Jessop initially resisted, but she eventually realized the only thing holding her back was her own stubbornness. Returning was an opportunity to “rebuild the place I love, rebuild the home that I lived in,” she says. But the Short Creek she returned to was different from the one she’d left.

Morgan Fischer

The town was in transition. Many members of the church still lived there, and FLDS members ran the city government and police force. Apostates were quite literally taking the homes of evicted FLDS members, causing tension. “It felt like there was a dark cloud over the entire Valley,” Jessop says. “People weren’t talking to one another. It find of felt like a ghost town, and it did not feel like we were wanted or welcome in any kind of way.”

In 2012, the U.S. Department of Justice sued Short Creek and Hildale, finding that the government and police force were acting on behalf of, and as a wing of, the FLDS church and Jeffs. A court order imposed independent oversight of the towns. In August of this year, two years before the oversight was set to expire, the DOJ released Hildale and Short Creek from monitoring, a sign post of how much has changed.

One such change was in Hildale city government. In 2017, Donia Jessop was elected as the town’s mayor, becoming the first ex-FLDS person in the position. Three other ex-FLDS members won city council seats. The election was not a sign of rapprochement with the FLDS community as much as a snapshot of the area’s changing demographics. Jessop and a slate of ex-FLDS candidates worked to register and win the votes of apostates. Electorally, FLDS members were considered something of a lost cause. With fewer than 400 registered voters in Hildale, Jessop won the mayoral race 129 votes to 81.

Not everyone is happy with the changes in Short Creek. Sitting at a large dining table in her Colorado City home, 16-year-old Kathy Bistline snacks on green grapes while recounting a recent visit to the Dollar General. She was wearing a hoodie and leggings into the store — not the typical floor-length prairie dress for Bistline, who is FLDS. “Whoa, getting your freedom?” the cashier cracked. The comment stung.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Bistline says. “Like, I don’t have freedom?”

Bistline now feels like the outsider in a town long defined by her own church. FLDS members are a common sight, but only around 6-8% of Colorado City residents and only 3% of Hildale residents are church members, says Voice for Dignity founder Christine Marie. The towns are mostly inhabited by ex-FLDS residents or newcomers with no prior connection to the church.

Bistline says she feels judged by people for her religion. Warren Jeffs still exerts influence on the church, but things have loosened up from the FLDS days of old. As she talks, Bistline’s hair is not in a braid but drapes messily over her silver Beats headphones. She’s home-schooled, but her family has a movie room. Still, Bistline — who has never known a world in which Jeffs is not behind bars — isn’t a fan of what Short Creek is becoming.

“It’s just scarier mostly,” Bistline says. “You feel like you’re being watched all the time.”

Short Creek’s past hasn’t been completely washed away. Rulon Jeffs’ “Keep Sweet” motto can still be found on a chimney pipe of the massive home that used to belong to him and his notorious son. The meeting house where the FLDS would worship sits vacant and tattered, a block away from the elementary school.

And when measles hit, very few were vaccinated, just as Warren Jeffs ordered.

Morgan Fischer

‘A day late and a dollar short’

With a largely unimmunized population to run through, the measles outbreak in Short Creek keeps growing. Keate says Hometown Wellness is trying “the best we can” to treat the influx of patients.

There are a lot of them. Hometown Wellness employees instruct patients to stay in their cars when they arrive, meeting them outside and spiriting positive or suspected measles patients through the back door to a secure area. Once inside, patients are given antibodies, intravenous fluids and ibuprofen. If a patient can’t kick measles, they may have to go to the emergency room 30 minutes away in Hurricane, Utah. If things get really serious, the closest hospital is an hour away in St. George. Anyone who is that sick is dealing with something more than just measles.

“It’s not why they have to go to the hospital,” Keate says. “It’s because of the secondary infection. Somehow it’s always pneumonia.”

Families have been hit hard. The daughter of one of Decker’s friends got measles, along with 10 members of the girl’s household. They’ve been quarantining. Garcia says five kids in another home in Short Creek got the disease. Everyone in that home weathered it well, except for a 16-year-old who had severe symptoms.

The outbreak has changed some tunes about vaccination. Keate says that when people see “how horrible it is,” entire families trek to get immunized, either at the Mohave County Health Department’s trailer-like nursing station off of Highway 389 or at the Creek Valley Health Clinic in town. From August through Sept. 21, the Creek Valley Health Clinic administered 689 vaccines to Short Creek residents, clinic CEO Hunter Adams says. Mohave County has not returned a request for its updated vaccination numbers.

Creekers who visit the beige health department trailer by the highway are often “a day later and a dollar short,” Keate says. They still end up getting measles because they’ve already been exposed. Keate works to educate patients about the need to be proactive, but some are resistant to vaccines. Others believe, erroneously, that the shot will give them measles rather than guard against it.

Even in this, Jeffs’ influence looms. Some Creekers are reluctant to get the vaccine because Jeffs said they shouldn’t. But as Short Creek changes, many others are hesitant for the opposite reason. For years in Short Creek, Jeffs dictated the decisions that governed people’s lives. Decades before that, the government tried to do the same, ripping children away from their families. As Short Creek grows, community leaders are “very careful not to push belief systems,” Donia Jessop says. You can hardly blame Creekers for being slow to trust.

“We push out education, but we don’t demand,” Jessop says. “Never again will we be told what to do.”