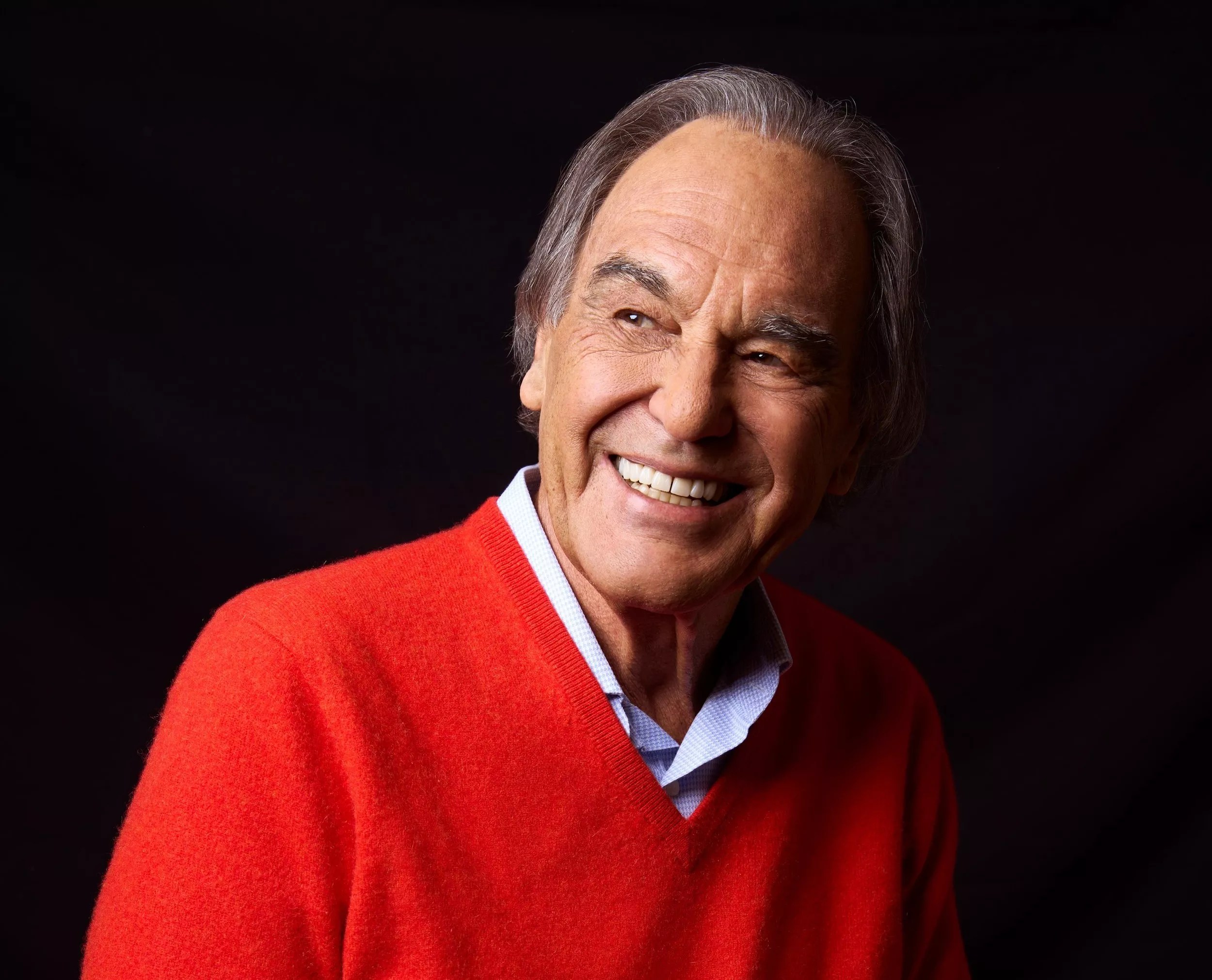

Regine Mahaux

Audio By Carbonatix

Most of the films screening at the 25th annual Phoenix Film Festival were made in the last few years. But on the evening of Saturday, March 29, the festival will screen “Platoon,” which was made in 1986 and won four Academy Awards the following year.

That night, the film will be followed by a reunion panel featuring director Oliver Stone as well as Keith David (“King”), Captain Dale Dye (technical advisor and “Captain Harris”), Mark Ebenhoch (assistant military technical advisor), Corey Glover (“Francis”) and Paul Sanchez (“Doc”) to discuss “Platoon” and the enduring bonds among the cast and crew of the movie. A screening of Paul Sanchez’s 2018 documentary, “Brothers in Arms,” about the making of “Platoon,” will occur earlier in the afternoon.

The screenings and reunion came about in an unexpected way.

“It’s so random,” says Jason Carney, Phoenix Film Foundation CEO and executive director of the Phoenix Film Festival. “One of the military advisors on the film, Mark Ebenhoch, has a relative in the Phoenix area, and he was talking to her about trying to get a ‘Platoon’ reunion together.”

That relative’s husband worked as a security guard at the festival many times over a decade ago. Calls and introductions were made, and by August of last year, Carney and Phil Bradstock, film commissioner in the City of Phoenix Film Office, were working with Ebenhoch to make the reunion part of the 25th-anniversary edition of the festival.

By January, Carney had involved Paul Sanchez, who played Doc in “Platoon.” At around the 30-year mark after the making of the film, Sanchez made his documentary, which features narration by Charlie Sheen and interviews with numerous cast and crew.

“Making Platoon was one of the greatest experiences of my life, one of the best times of my life,” Sanchez says. “‘Brothers in Arms’ is a love letter to ‘Platoon,’ to those actors and to Oliver.”

The story begins long ago, almost two decades before “Platoon” was filmed. In 1967, Stone, then in his early 20s, enlisted in the United States Army and served in combat in the Vietnam War. Stone ultimately earned several military decorations for his conduct, including the Purple Heart and Bronze Star. Upon returning to the United States after his service, Stone wrote a screenplay based closely on his experiences, but was unable to get it produced. He persisted in his ambition of making a movie about the Vietnam War, going through many rounds of writing and rewriting scripts and seeking funding, encountering significant resistance because of the continued controversies and unresolved tensions of the Vietnam War.

Only in 1986, after a number of screenwriting successes with films such as “Conan the Barbarian” and “Scarface,” was minimal but sufficient funding secured.

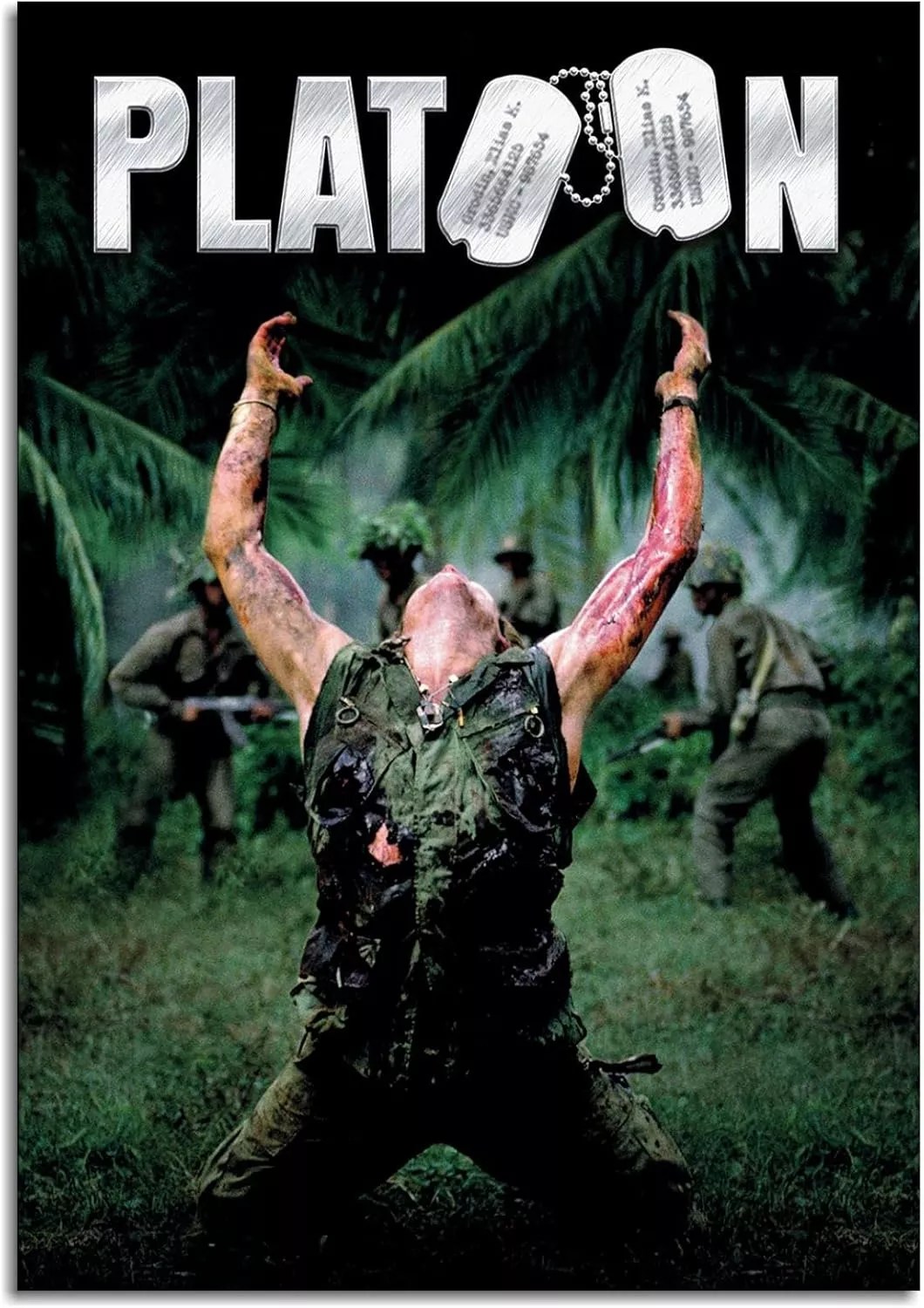

Willem Dafoe is pictured on the iconic “Platoon” poster.

Orion Pictures

Although many of the “Platoon” actors are quite famous now, 38 years ago, most of the actors were just starting out. Charlie Sheen, who was already part of the Hollywood milieu because of his father, Martin Sheen, was a notable exception. Sanchez recalls it as a time when he had done a lot of stage acting and had earned his Actors’ Equity card, but had not yet broken into film. “Out of the 31 actors,” he says, “it was the first film for about 26 of us.”

The Philippines had been selected for filming, both for the climate and landscape similar to Vietnam’s and because the government had agreed to provide helicopters and other equipment that the U.S. State Department had refused because of its disapproval of the film. The cast and crew arrived in country in early 1986 amid social and political upheaval as opposition to the corruption and violence of the Marcos regime. “There were tanks in the streets,” Sanchez recalls. “Marcos wouldn’t leave.”

At 4 the next morning, a very tired and very drunk cast began their new gig.

“We were assembled and given some trousers, some equipment,” Sanchez says. “We got in some vans, and they drove us hours and hours into the jungle.”

It was there, far from hotels or medical facilities or even telephones, that the cast and crew spent nearly all of the next two months, starting with a boot camp run by military technical advisors who aimed to make the actors’ experience of filming as much like actual combat as possible. That immersion into the life of a grunt began with the actors digging foxholes for makeshift sleeping quarters, though they got little rest between pulling sentry duty and counterattacking the military advisors’ staged ambushes (which included very real explosions).

The film was shot chronologically, an uncommon practice in filmmaking. Sanchez recalls the first day on-site as physically grueling, with the men bearing up under the heat and humidity and hacking their way through the jungle, jet-lagged from 36 hours of travel and hung over from drinking much of that time.

“We were hung over and hating the world, humping through the jungle wanting to fucking kill somebody,” Sanchez recalls.

They thought the forced march was an exercise, part of rehearsal such as it was. There was grumbling and kvetching among the would-be grunts, and barked orders from would-be officers that there would be no talking in the ranks. The march went on and on, without any apparent purpose or destination.

“And all of a sudden, we saw cameras,” Sanchez says. “That was the first shot of the film.”

Over the next several weeks, the program of pushing actors up to and beyond physical and emotional limits continued. They slept out in the open, kept watch at night, made patrols, dug and took cover in holes and ate MREs, the military’s infamously unpalatable packaged processed food.

“It was bad luck if you got bean component,” Sanchez says, recalling the most detested of all MRE varieties. “It was so bad they didn’t even give it a name. (Johnny) Depp got that three times during those weeks.” And they did it all in humidity over 90 percent, temperatures about the same and with 100-pound rucksacks.

Sanchez also recalls Stone’s gruff, often harsh, manner and his penchant for disparaging actors, often with extensive profanity, to get them so completely into the experience as to almost not be acting.

“He would use us,” Sanchez says of Stone. “In my film, I called him a dark, evil genius.”

As Sanchez remembers it, Stone would do just about anything to get the actors into the mindsets he wanted them to have. In one instance Sanchez recalls, Stone thought Sheen looked a little too rested, so the director had him carry water buckets back and forth while shirtless in the background of another scene. Sheen wondered if the buckets should be empty on the way back for realism. Sanchez remembers Stone saying, “Don’t worry about it.”

The chronological shooting also aided the actors in portraying grief. After filming scenes in which characters die, those actors would be flown out, never to return to set.

The actors, enduring such emotionally and physically brutal filming conditions, developed lasting bonds of a rare sort.

“I grew up surfing and played football, and I don’t talk to any of those guys, “Sanchez says. “But these guys, it’s going to be 40 years, and I talk with them all the time. I just spoke with Charlie (Sheen). I know exactly when Willem (Dafoe) will get to his new shoot. Tom (Berenger) is going to be in Egypt, so he couldn’t make it (to the festival). No one could hold it together – this bond or whatever – like this if it was insincere.”