Jenny Risher

Audio By Carbonatix

We wouldn’t have Alice Cooper the shock-rocker without Alice Cooper the band, the one that launched under other names from 1964 Phoenix, then honed a razor-sharp edge in psychedelic Los Angeles before heading to Detroit.

With that sort of longevity come milestones. This month Cooper’s platinum-selling solo debut, “Welcome to My Nightmare,” rang in its 50th anniversary. And 60 years ago, his high-school quintet, the Spiders, recorded their debut single.

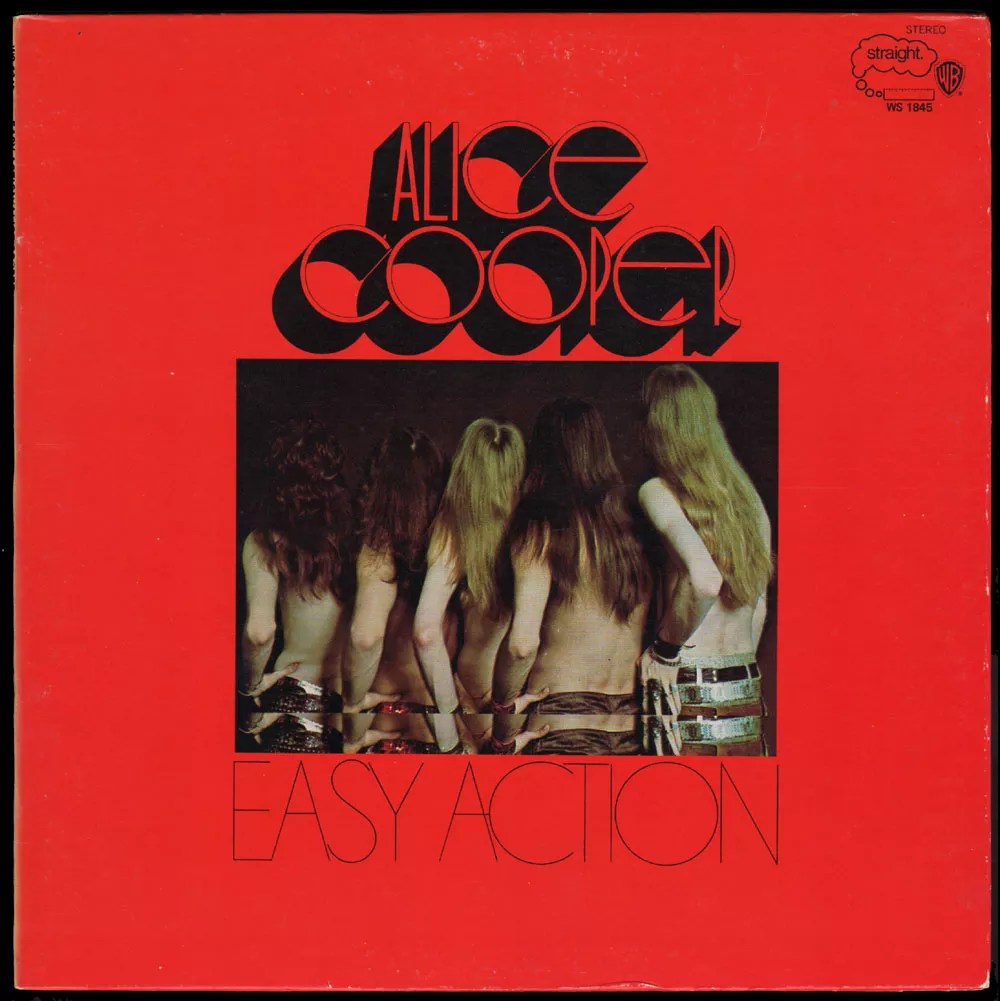

Right now, let’s split the difference and look back 55 years to early group’s vastly overlooked second LP, “Easy Action.” It was released seven months before the post-adolescent anthem “I’m Eighteen” changed everything, and reviewed only tepidly at the time. Yet it merits another listen as “Action” celebrates its 55th year – at top volume, hopefully – five days after Cooper’s March 22 stand at the Wild Horse Pass Festival Grounds in Chandler.

A glimpse into that era begins with a visit to the young, familiar face grinning in Cortez High School’s 1966 yearbook. The boy’s accomplishments occupy a portion of the page’s left side. They identify Vincent Damon Furnier, the Detroit-born pastor’s son whose family moved to Phoenix when he was 11, as a multi-sport athlete (track and cross country), a member of his school’s lettermen and art clubs, and a writer for the school newspaper, the Tip Sheet.

Above those distinctions, however, rests the following statement:

“Ambition: A million record seller.”

Attribute such dreams to the tongue-in-cheek brio of youth, but here it turned out to be true.

Well, sort of. It’s off by about 49 million.

The future Alice Cooper was already a rocker then, and not just in spirit. He’d formed The Earwigs as a junior in the fall of 1964 with seniors and cross-country teammates Dennis Dunaway, Glenn Buxton, John Speer and John Tatum. An Oct. 24 Arizona Republic article unveiled them in matching yellow jackets and black turtlenecks, which better fit a rejected name, Joe Banana and the Bunch. “Our motto,” Dunaway joked at the time, “‘music with a-peel.'”

Of the five, only Buxton and Tatum had musical experience, both on guitar. Dunaway and Speer quickly took up bass and drums while Furnier acquainted himself with harmonica. The youthful unit developed original material but also enjoyed refitting hit songs with humorous lyrics, like when they tweaked the Beatles’ “Please Please Me” to begin “Last night I ran four laps for my coach.” (Write what you know.)

Yet by 1965, The Earwigs took this extracurricular pursuit more seriously, evolving from insect to arachnid to become the Spiders. They replaced local sensations the Vibratos – once hailed as the “Beatles of Phoenix”- as house band at the VIP Club, owned by hyper-hyphenate Jack Curtis, an impresario who ran night spots, promoted shows, hosted his own KTVK half-hour and even wrote newspaper columns. He whisked them into Floyd Ramsey’s Audio Recorders of Arizona, where they waxed their first 45, a switchblade-moptop-by-way-of-Them original called “Why Don’t You Love Me,” backed by Marvin Gaye cover “Hitch Hike,” for Curtis’ Mascot label.

The following January, the Spiders backed actor Thomas Hasson’s Conrad Birdie in a Phoenix Star Theatre (now the Celebrity) production of “Bye Bye Birdie,” though their amplification reportedly devoured the titular wonder’s vocals. That October, they hit Tucson’s Copper State Recording Company for the sneer-boiled “Don’t Blow Your Mind” and its flip, “No Price Tag,” with new rhythm guitarist Michael Bruce in for Tatum, who’d split to start another group with future Tubes guitarist Bill Spooner.

‘Freaky rock and instrumental hangups’

The Spiders mutated into Nazz and moved to L.A. sometime in 1967 (a December Republic blurb lists Furnier’s Venice Beach address), although they appear to have returned to Arizona often, recording the scorched “Lay Down and Die, Goodbye” and heart-sunk moper “Wonder Who’s Loving Her Now?” in Phoenix. After returning to Southern California, Speer left the lineup, replaced by drummer and Camelback High graduate/Glendale Community College art classmate Neal Smith, then staying with the band in Santa Monica.

The erstwhile Nazz at last became Alice Cooper after learning that Todd Rundgren had already swiped that eureka. Permanently christened, they traversed a small circuit through Southern California – Santa Monica’s short-lived (but retrospectively famous) Cheetah and West Hollywood’s legendary Whisky a Go Go among their regular stops – New Mexico and, of course, their hometown. In February 1968 the now-bountifully-tressed Furnier, who adopted his group’s name as his own, surfaced in a Republic photo illustration accompanying religion editor Marie H. Walling’s expose on the changing faces of the church.

That April the quintet opened benefactor Jack Curtis’ “acid-rock” joint, which, interestingly, as per a local brief, was also called Alice Cooper’s but didn’t enjoy a similar longevity. Four months later, he beckoned them back for the four-hour Levity Ball (also on the bill: the Red, White and Blues Band, featuring Charles Lempriere “Prairie” Prince and Roger Steen, later Spooner’s partners in The Tubes) at the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum, which inspired an Alice Cooper song of that title. A Cheetah-captured version landed on their first full-length, “Pretties for You,” which Frank Zappa and his manager Herb Cohen issued in summer 1969 via their Bizarre/Straight label, distributed through Warner Bros.

The theatricality and rebellion of “Easy Action” became hallmarks of Alice Cooper performances for the next half-century.

Alice Cooper

With its electric squirms and stop-start stomps, “Pretties” exists today as an example of the carnal young outfit tamed in a studio. “[T]he music … is quite comfortably at home in the ‘heavy psychedelic’ category, whatever that means,” Scott G. Campbell shrugged in the Republic. But perhaps on record it’s too comfortable, too crisp even in structured collapse. One possible explanation: The band reportedly produced it after Zappa exited Burbank’s Whitney Studios, leaving his unchaperoned charges to fire-harvest dubious leaves – a gift from Jefferson Airplane – during the sessions.

“I guess [Frank] never worked around anyone that was stoned,” drummer Neal Smith told Serge Nadeau in 2004. “He did come back in a few days later to help with the final mixes. The whole album was completed in a week or so. For all practical purposes, it was recorded like a live studio album.”

That’s the proper way to experience Alice Cooper, anyhow. Then, as now, they were a theatrical indulgence best consumed in person. “Pretties” in looser form haunts Rhino’s “Live at the Whisky a Go Go 1969,” released in 1992. (That title’s year may be incorrect; a Setlist.fm note suggests the performance took place July 23, 1968, though the band played the Whisky at least 15 times those two years.)

A gnarly energy dominates. Pamela Des Barres, of Girls Together Outrageously and author of 1987’s “I’m with the Band,” was there and described the night as “lunatic.” Warner Bros. Records executives Mo Ostin and Joe Smith were frozen aghast as the dress-draped frontman dismembered dolls and fed himself to a prop guillotine, a longtime spectacle I beheld years later with my own eyes. Alice Cooper twice reference their Southwest bona fides: “Today Mueller,” according to a spoken intro, involved a Phoenix girl, while “Nobody Likes Me” was allegedly written after “we were kicked out of Chandler,” though no one seems to elaborate.

Sonically, the concert reveals “Pretties” as an intricately warped feral orchestra threatening at all times to untether. Imagine Syd Barrett Pink Floyd eccentricities colliding with post-British Invasion sensibilities and florid shards of Karlheinz Stockhausen into a brutal Motor City scatter. (“Levity Ball” bears traces of Pink Floyd’s “Astronomy Domine.” “Reflected” is toothsome Stooges-ish punk funneled through the Who, foreseeing the Ramones and informing Cooper’s own petulant “Elected” in 1972.) The live presentation ends, as its studio counterpart does, with “Changing Arranging,” a fuzzy avalanche of guitars, drums and skronk galloping in abrupt skids toward dissonant destruction.

‘Here’s new pretties for you’

What to do for an encore? Alice Cooper reconvened in late ’69 at Pat Boone’s Sunwest Recording Studios in Hollywood, likely with no intention of honoring its pop-star proprietor’s catalog. Producer David Briggs, then between Neil Young slabs, allegedly wasn’t enamored of the quintet’s psychedelia. Which was fine. They were flirting with rougher territories anyway.

As a result, 1970’s “Easy Action” seethes harder than its predecessor. Its reckless rebellion finds the rugged road onto which Alice Cooper would soon swerve. That’s evident on opening track “Mr. and Misdemeanor,” when the former Vince Furnier inaugurates the snarl that became Alice’s speaking voice, channeling a late-era Jim Morrison opposite Glen Buxton’s Robby Krieger.

This throatier guise resurfaces on “Return of the Spiders (for Gene Vincent),” already a master emcee threatening (or vowing) unspeakable thrills behind closed curtains. “Well, stop! Look! And listen!” he barks, teasing allusions to certain death. Other tracks require softer touches. He revives happier inflections on “Shoe Salesman’s” sunny park strum-stroll – a curious momentum for a song about addiction. Rhythm guitarist Michael Bruce dons McCartney lilts for thorny rocker “Below Your Means,” which jams into extended swapped six-string punches, and over his own “Beautiful Flyaway” piano daubs.

The disc vacillates between the vanishing Aquarian age, with its wider canvases, and the unknown’s sinewy violence. “Shoe Salesman,” “Laughing at Me,” “Refrigerator Heaven” and “Below Your Means” may all have worked on “Pretties.” Other chunks were rooted in something older: an affection for 1950s musical “West Side Story.” Second-in-command Jets gang member Diesel Smith uttered the title in the song “Cool.” Show nods land in “Still No Air,” with its guitar-sirens grabbing for oxygen as “easy action,” “got a rocket in your pocket” and “When you’re a Jet, you’re a Jet all the way / from your first cigarette to your last dying day” slide past. The band would extend those last lines past throwaway homage on “Gutter Cats vs. the Jets” from 1972’s “School’s Out,” requiring the songwriting-credit inclusion of Stephen Sondheim and Leonard Bernstein.

But overall, this is a more savage Alice Cooper. Guitars rage urgently, interrupting and strangling one other across “Means” and “Spiders.” Nowhere is this plainer than on free-form closer “Lay Down and Die, Goodbye,” unknowingly prefaced by comedian Tom Smothers of the Smothers Brothers assailing the content-related controversies he endured on his CBS series, “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour.” “You are the only censor,” he advises. “If you don’t like what I’m saying, you have a choice. You can turn me off.”

Which doesn’t appear to be an option here, hauling listeners through drum thuds and squalling twin wah-wahs in a 7-minute tapestry. And that doesn’t compare one iota to the scuzz-thunder riff Buxton saws through the center. The only resemblance it bears to the number Alice Cooper recorded as Nazz are its final lines, swiped from the original’s chorus. All else is chaos.

Such changes were inevitable, of course. The shadowy promise of naÁ¯ve ’67 was dead, and a harder decade skulked in wait, redolent of ugly horror. Constantly challenged optimism can’t last. Everything grew darker, perfect for Alice Cooper. “Easy Action” struck the right opening note, even if ears couldn’t quite grasp it yet. (“[D]on’t bother with their album,” Cincinnati Enquirer contributor Jim Knippenberg cautioned. “It’ll probably bore you.” They’d never be accused of that again.) But a half-year after its release, and the subsequent arrival of “I’m Eighteen,” the universe was ready to listen.