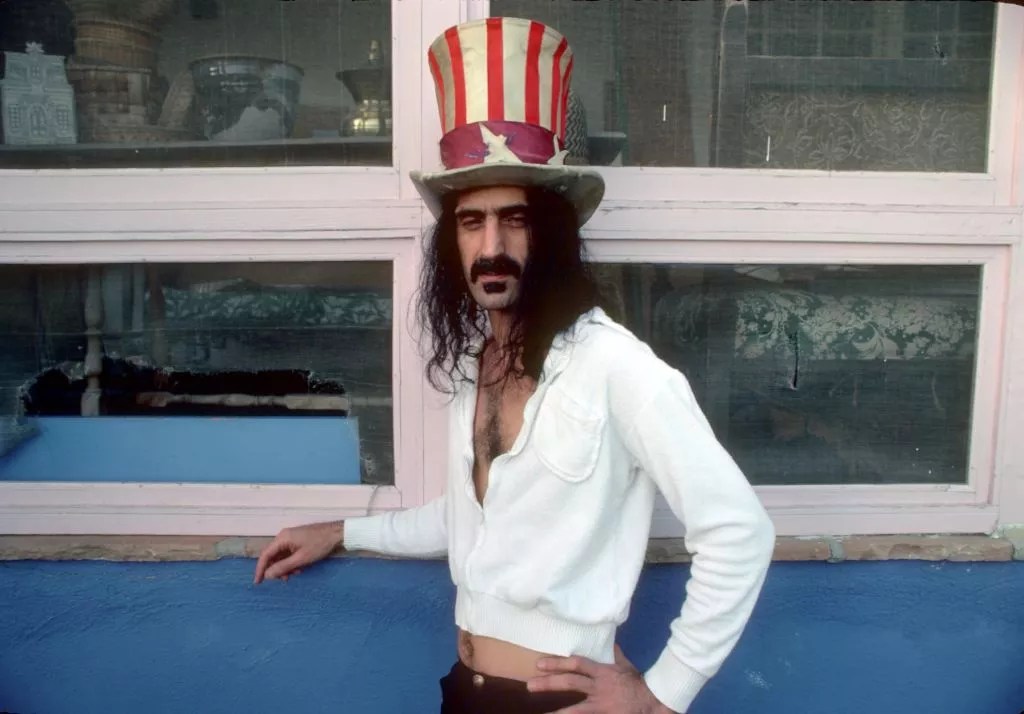

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

“My humble curse: May your shit come to life and kiss you.” – Frank Zappa, “The Real Frank Zappa Book” (1990)

In death, Frank Zappa lives.

You don’t have to know his work. Such is the digital afterlife: it’s there if you care to listen. We venerate his intellect and humor, his Nostradaman talent to foretell the direction of the culture-at-large. His mustachioed smirk invades my feed weekly, wryly destroying some long-dead jowl-bot on CNN’s “Crossfire,” a chatterbox cabler that passed for bipartisan ’til the Limbaugh-Gingrich GOP swaggerfest and was mercy-chloroformed in its Tucker Carlson bowtie with an assist from Jon Stewart.

I remember Frank. He’s always been “Frank” to me. That journalistic convention of references by surname has somehow never applied. Frank I discovered in myriad ways: my father’s copy of 1982’s “Ship Arriving Too Late to Save a Drowning Witch,” a Top 30 LP bolstered by the “Valley Girl” single he waxed with teen daughter Moon Unit; the ritual unfurling of 1977’s “Titties & Beer” at out-of-town softball tournaments; and, finally, my own acquisition of 1968’s “Cruising with Ruben & the Jets” during the late-’80s Rykodisc/Barking Pumpkin reissue blitz.

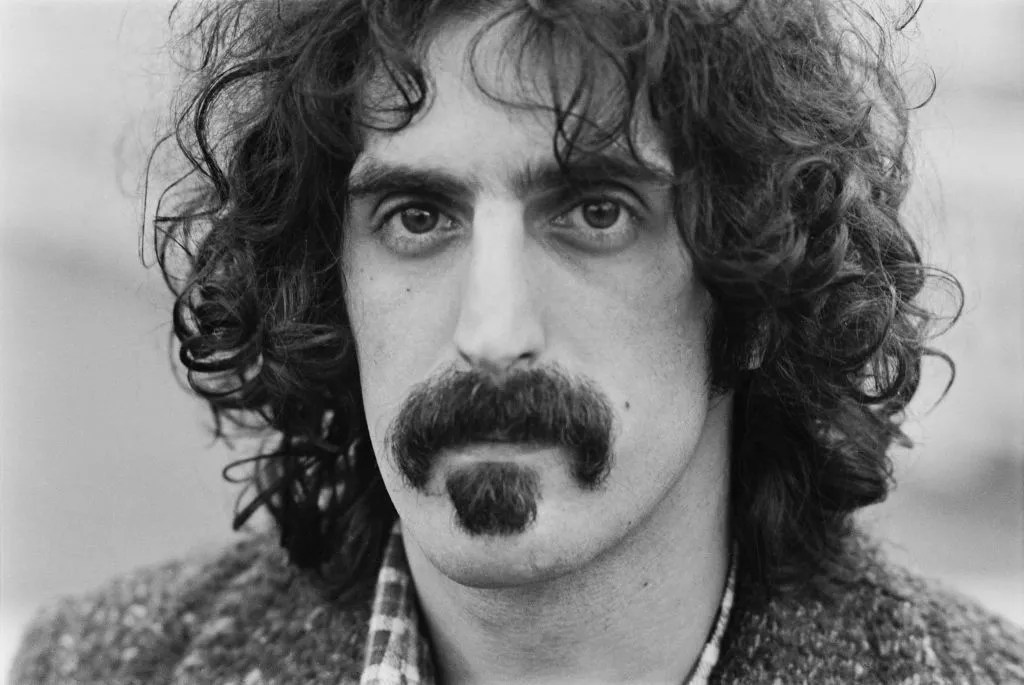

American musician and composer Frank Zappa (1940-1993) at the Oval ahead of the ‘Rock at the Oval’ festival at the cricket ground in Kennington, London, England, September 14, 1972.

Jack Kay/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

That was my true intro: The Mothers of Invention in subterfuge, clad in doo-wop, committing fully to the lie with verbiage on pompadour maintenance, harmony-jammed uvulas and midcentury virginal bubblegum jabber filtered through Stravinsky. Of course, that artifice falls in the last 4 minutes and 37 seconds with “Stuff Up the Cracks,” a puppy-love-lost suicide ode with an outro wah-wah moan no ’50s whiffer coulda/woulda matched in his lifetime. It’s like snarfing ice cream ’til you hit warm spaghetti.

Frank was an interesting cat to discover in the ’80s, as a previous generation deified the Summer of Love. Its passionate cries became saleable slogans, its counterculture heroes nostalgia-funneled capitalism. Confusingly, some of the mainstream pinned Frank as a ’60s figure, too (others considered him a public enemy, if not No. 1, then at least in the American Top 40), though anyone who’d given 1968’s “We’re Only in It for the Money” even a cursory audience would have dumped such perceptions in seconds.

The bandleader’s crew bore passing resemblance to hippies, as that was then the fashion, but their disc unmasks that oft-borrowed lifestyle as untenable and as fake as the “straights” it purports to assail. (“Money” doesn’t let them off, either.) Lampooned in those grooves were starry-eyed tourists chasing low-rent thrills in “Frisco,” where they’d drop acid and sleep off Fillmore freakouts nose-to-nose with Owsley Stanley (“Who Needs the Peace Corps?”). As that echo claimed so plain in “Absolutely Free,” “Flower power sucks.”

That’s what I liked about Frank. He’s what I call a true liberal or, well, maybe more of a play-by-play anthropologist. Today, we congratulate such gadflies for a “both sides” fairness, a common canard that makes them sound like deliberate scorekeepers and cheapens what the best ones do. No, a true liberal – like Frank, like George Carlin (long misappropriated by those who know him only from YouTube/TikTok swallows, who can’t explain the difference between “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television,” with its many amendments, and “Asshole, Jackoff, Scumbag”), like the aforementioned Stewart – exposes the inherent hypocrisies of humankind. And hypocrisy follows no tribe. Progressive, conservative: we’re all of us guilty.

Over the years, I’ve consulted Frank’s work as a barometer of my own growth. Where do we split? Where do we agree? And what the hell has happened to me?

This is the Central Scrutinizer

“There’s 75 million people in our country in the Baby Boom generation: 3.6 million of those earn $35,000 or more [annually] while at the same time, 32 million earn $10,000 or less. … In other words, for every entrepreneur riding around in a Porsche, there are eight single mothers with kids sucking the glue off food stamps. They just happen not t,o make the pages of People magazine.” – Abbie Hoffman, “The Last Debate” with Jerry Rubin, Orpheum, Vancouver, B.C. (Saturday, Feb. 8, 1986)

Author Bradley Morgan wrestles with his own relationship with the artist for “Frank Zappa’s America” (LSU Press, June 2025), using as its foundation his 2022 Pop Matters thinker on 1979’s three-act “Joe’s Garage.”

Within, Morgan linked the album’s satire to that year’s Iranian Revolution, as well as prevalent dogmas then ascendant in the United States, when faux Christianity sought a piece of the pie, shedding theology for political power lust. (J.C. proved a no-show, forcing televangelist mogul Pat Robertson to fling his thorny crown ring-ward.) That record, with help from the incoming decade itself, lit the path to Frank’s most crushing ’80s works, the thrust of Morgan’s 320-page study.

While “America” does explore the early canon, it focuses on “Freak Out!” (1967) and “We’re Only in It for the Money” – no “Road Ladies” dissertations, no “Willie the Pimp” to prod – before leaping to “Garage,” then “You Are What You Is” (1981), where we discover that Frank’s America, no surprise, is ugly as shit.

The cultural decade had given way to the Me Generation, into which galloped President Ronald Reagan, former California governor and counterculture adversary, on a Morning in America nag reupholstered as a steed. Hippies became yuppies – even Yippie leader Jerry Rubin, who’d channeled his talents for attention-grabbing activism into rebirth as a business networker. (Though he was hardly a “sellout”; as he relayed in 1976’s “Growing (Up) at 37,” the movement declared him too old and famous, so he found other ways to persevere.) Few spoke of communes and social harmony anymore; replacing those ambitions were stocks, aerobics and Quiche Lorraine.

The Baby Boom split into haves, have-nots and gimmes. Perhaps they’d once united against the system, but class and circumstance shoved them in other directions: gleaming metropolises, bland suburbia, ridiculous wealth, grim poverty. Some remained political liberals but became fiscal conservatives and, worse, conspicuous consumers.

When artists like Bruce Springsteen released palpable struggle-of-the-union anthems like “Born in the U.S.A.” and “My Hometown,” the GOP adopted them as working-class-resilience porn. (Then and now, the party waves blue collars as folkloric avatars, yet does little substantive on their behalf.)

Republicans represented patriotic strength, American nerve, the victory of old-time values. Democrats seemed as unmoored as they’d been in ’68, desperate for an electable champion. Following Jimmy Carter’s loss to Reagan in November 1980, they wouldn’t see the Oval Office without chaperones until 1993, the final full year of Frank Zappa’s life.

A dungeon of despair

High Times: It’s a bizarre thing – you ask kids what they want to be when they grow up, or what they want to do, and their answer is, “I want to make money.” In a survey among high school students, more kids said Donald Trump was their hero than anybody else.

Frank Zappa: Yeah, but on the other hand, let’s deal with it as a fact of life in America. I think that’s a very good indicator of the failure of U.S. education. Now, if you add these two facts together, Donald Trump is the idol of American teens, and these teens can’t read, write, or do arithmetic, what do we have?

HT: What?

FZ: A failure to communicate. – Elin Wilder, “Frank Zappa: Somebody Up There Doesn’t Like Me,” High Times, December 1989

Morgan’s book makes clear the abundant links between the ’80s and 2024-5. In fact, we’d call our era “Reaganism on steroids” or “Reaganism from hell” were those not ’80s shibboleths themselves. (“Reaganism 2.0” is just ass.) It’s more like a dystopian fairy tale read to the dying Jesse Helms to ease him into the afterworld.

How fitting, then, that the nation’s now overlorded by an ’80s pop-culture relic. Unfortunately, neither the Noid nor the California Raisins earned 21st-century comebacks in fiction about their business savvy. They’re just novelties mothballed some 35 years ago.

While Morgan rightly refrains from speaking on modern Frank’s behalf, I think he’d be amused but not surprised by what passes for political discourse. He might see Donald Trump as the figurehead we deserve. After an actor who pretended to be a cowboy, why not a rich celebrity cosplaying wrestling heel/Internet troll populism? All I can say for Reagan is that he, at least, was cognizant enough to feel, whereas Trump, born into money, governs as someone whose every whim’s been overindulged.

The chapters “The Meek Shall Inherit Nothing” and “The ‘Torchum’ Never Stops” tackle the troubling truth that racism is baked into the American dream, and no volume of well-intentioned enlightenment can dismantle it. As outlined in “Meek,” the “You Are What You Is” LP, in part, mocked shameless white appropriation of other cultures, hijacking their hardships for status, in effect minimizing those accomplishments. It’s very American even now to claim struggles that aren’t your own, ’cause ain’t that what this country’s all about: hardiness and bootstraps, triumph over an oppressive Them?

“‘Torchum'” deconstructs 1984’s “Thing-Fish,” one of Frank’s most problematic releases, a proposed stage production conjured during a period when the AIDS virus collided with conservative indifference. Satirically digging at “Amos ‘n’ Andy” iconography, the disc – featuring bandmate Ike Willis as main interlocutor – freely speaks that controversial vernacular and makes for a difficult listen akin to the pitiably backward narrators populating Randy Newman’s “Good Old Boys” (1974). I’ve owned it since the ’90s and have listened to it maybe twice, typically bypassing “He’s So Gay,” where Frank’s humor, intent and pinpoint potency aside, hasn’t aged well. In his defense, the tone’s very of its time; to wit: Josie Cotton’s “Johnny Are You Queer?” (1981).

Morgan ably articulates the quandary of examining the record, dancing between its original motivation and ultimate effect. “[I]t is an album,” he writes, “that has had a complicated legacy for 40 years, and it has yet to see a reappraisal worthy enough to reverse that, despite the efforts of a whole lot of white guys writing about it, including myself.”

My favorite chapters cover aspects of the ’80s I fiercely recall. “Porn Wars” tracks the embarrassing Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) and its useless 1985 hearings on apparent sonic filth. All that did for this suburban teen was transform Frank Zappa, Twisted Sister frontman Dee Snider, and John goddamn Denver, of all people, into First Amendment heroes, then make me think long and hard in my late 20s about voting for Al Gore in the 2000 presidential race, because of his then-marriage to coalition cofounder Tipper Gore.

The PMRC tried to brand itself a movement of concerned parents, but it was hard to ignore the prominent and prominent-adjacent figures comprising its body. Colloquially, they were called the “Washington Wives,” raging against the “Filthy Fifteen,” one being Prince’s “Darling Nikki” – which the Gores’ oldest daughter, Karenna, innocently brought home – and another being W.A.S.P.’s “Animal (Fuck Like a Beast),” a title Susan Baker, wife of U.S. Secretary of the Treasury James Baker III, pronounced in testimony as “eff-you-see-kay.”

They called for a ratings system, resulting in the “Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics” sticker many bands used as an illustrative element or selling point. Frank dismissed the PMRC’s efforts – to its members’ faces, even – as “an ill-conceived piece of nonsense.” Months later, he took it further with “Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention” (1985), complete with a warning of his own that the record “contains material which a truly free society would neither fear nor suppress.” PMRC members guest-starred on the track “Porn Wars,” their words twisted into self-mockery, though their descendants continue to court opprobrium by invading libraries and school boards to ban books and fire “woke” administrators, all while bemoaning “cancel culture.”

“Jesus Thinks You’re a Jerk” follows Frank into his and Reagan’s twilight; he’d unknowingly released his last studio album, the instrumental “Jazz from Hell,” in 1986, then concentrated on live releases. “Broadway the Hard Way” (1988) has the distinction of featuring new music, all of it targeting such luminaries as Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, Pat Robertson, Jesse Jackson, Michael Jackson, Richard Nixon, and the outgoing president. Even Sting turns up to skewer televangelist Jimmy Swaggart in a performance of The Police’s “Murder by Numbers.”

As Morgan reminds us, the fundamentalism peddled by the late Swaggart (a married pew-chiseler and Dirty, Dirty Boy) and his ilk represented a poisonous bloc that continues to rule politics even as proponents are repeatedly exposed as heretics. You may recall that Robertson ran for president in ’88 and held on into April before dropping out. Donald Trump considered contending as a Republican that year and reportedly even asked eventual victor George H.W. Bush’s campaign adviser, the irascible Lee Atwater – from whom the future leader stole a trick or two, save blues guitar – for the veep seat. Bush declined the suggestion. Despite these minor setbacks, Trump and Robertson, an unlikely pairing, eventually won.

Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention pose for a portrait in circa 1968.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

This is Phaze III

“The thing is to put a motor in yourself.” – Frank Zappa, “This is Phaze III,” from “Civilization Phaze III”

Frank didn’t live to suffer that; in 1990, he was diagnosed with cancer, and his earthbound time was short. Yet he remained true to his nature, a contrarian to the end. He may have left us in ’93, but musically and culturally, he never, ever shuts the fuck up. And that’s great, ’cause we’ll never not need him. “With so much left to say and so little time to say it,” Morgan writes, “the message Zappa would leave behind for listeners is one we have been grappling with for decades and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.”

Sadly, I foresaw nothing. After reading “Frank Zappa’s America,” all I did was obsess over how the passage of time seldom suggests advancement of thought. Due to conflicting tenets, Democrats are as lost as they’ve ever been. Loud, righteous gatekeepers demand perfection from candidates with purity tests they couldn’t pass themselves. They prefer the passion of rallies to the boredom of voting.

Meanwhile, modern conservatives strangely continue to promote their ranks as perennial underdogs battling the “establishment” despite having controlled the White House for 30 of the last 52 years. In fact, Republicans historically lead Democrats as holders of the highest office, 19 to 16. Plus, it’s hard to be underdogs when you’ve dominated the House and Senate simultaneously three times since 2015, 25 overall after your party’s 1854 foundation. (Democrats: 23 total, once since 2011.) Which means that, fluctuating ideologies notwithstanding, these allegedly persecuted outlaws have represented the “establishment” a lot.

If I miss anything from the 1980s, it’s the lack of an unquenchable thirst for outrage and less political cheerleading from the masses, otherwise ignorant of politics.

I did, however, find solace in this book. In the prologue, of all places, as author Morgan rides the “L” train through Chicago’s River North neighborhood to glimpse Columbia College professor Adam Brooks’ 72-foot-high “Freedom Wall,” stamped to the exterior of 325 W. Huron St., upon it are the names of 69 people. John Brown. Jimmy Carter. Anne Frank. Winston Churchill. Ruth Bader Ginsburg. James Joyce. And right there between Václav Havel and Carl Djerassi: Frank Zappa. He shares space with Jack Kevorkian, Rush Limbaugh, and, of course, Ronald Reagan, but, as Morgan proclaims, “[H]e embodies the concept of freedom for me.”

Frank’s and our America come up short, but that such people existed, and that their work continues to inform and inspire, is enough to drive dreams of better.

Suggested reading:

- H.T. “Tom” Brown, “Confessions of a Zappa Fanatic”

- Kevin Courrier, “Dangerous Kitchen: The Subversive World of Zappa”

- Andy Greenaway, “Zappa the Hard Way”

- Abbie Hoffman, “Square Dancing in the Ice Age”

- Tom McGrath, “Triumph of the Yuppies: America, the Eighties, and the Creation of an Unequal Nation”

- Jerry Rubin, “Growing (Up) at 37”

- Greg Russo, “Cosmik Debris: The Collected History & Improvisations of Frank Zappa”

- Neil Slaven, “Electric Don Quixote: The Definitive Story of Frank Zappa”

- David Walley, “No Commercial Potential: The Saga of Frank Zappa”

- Ben Watson, “Frank Zappa’s Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play”

- Frank Zappa, “The Real Frank Zappa Book”

- Moon Zappa, “Earth to Moon: A Memoir”