Courtesy of Cory Frye

Audio By Carbonatix

I first heard his name in relation to another name, a man of even another name still: comedian Lenny Bruce, born Leonard Alfred Schneider in 1925.

It’s a famous story, damn near apocryphal – embellished over decades, punchlines emboldened in every retelling.

But we’re journalists, for Chrissakes. Here are the facts as we know them.

Lenny worked two shows Saturday, Nov. 30, 1963, at the Village Theatre in New York, taking the stage at 8:40 p.m. and midnight.

Few accounts of the evening exist. The Times sent no one. But an occasional contributor, Columbia University professor/bop-quaffer Albert Goldman, apparently turned up and recorded it – or at least possessed a recording he later consulted for his Yiddish-bombed, zip-pow New Journalism autopsy “Ladies and Gentlemen – Lenny Bruce!!” in 1974.

The early show seemed uneventful, notable for a man whose mouth sent him to jail. Plainclothes were known to rise from a nightclub’s depths, storming stages to slap him in cuffs. “All right, show’s over, ladies and gentlemen,” they’d harrumph, no sense of timing.

The second audience was hipper. Lenny could get away with more. When he emerged, though, nothing. Not a word, zilch, zip. Then it hit, brother, lightning, first as a whistle, then as a headshake.

“Wow! Boy!” he opened, issuing a sound like a small, lit fuse: “Sssssss!”

And then: “Poor Vaughn Meader!”

At that, the crowd exploded. Everyone knew what he meant.

So, what did he mean?

And who the hell’s Vaughn Meader?

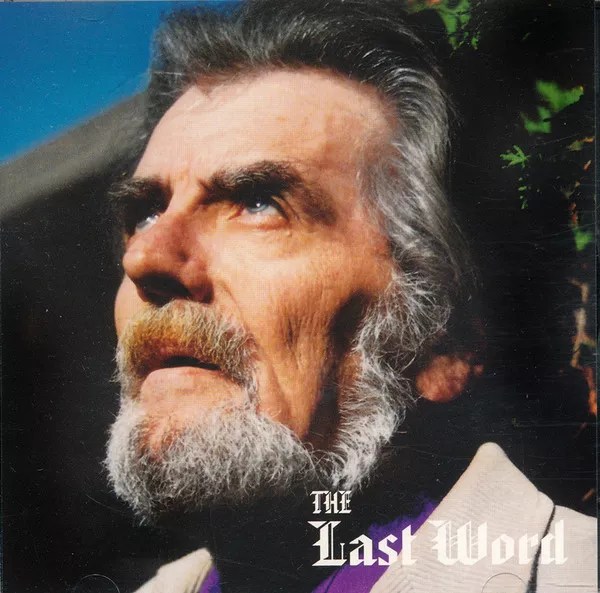

“The Last Word” CD cover

Courtesy of Cory Frye

Thrift cream and other delights

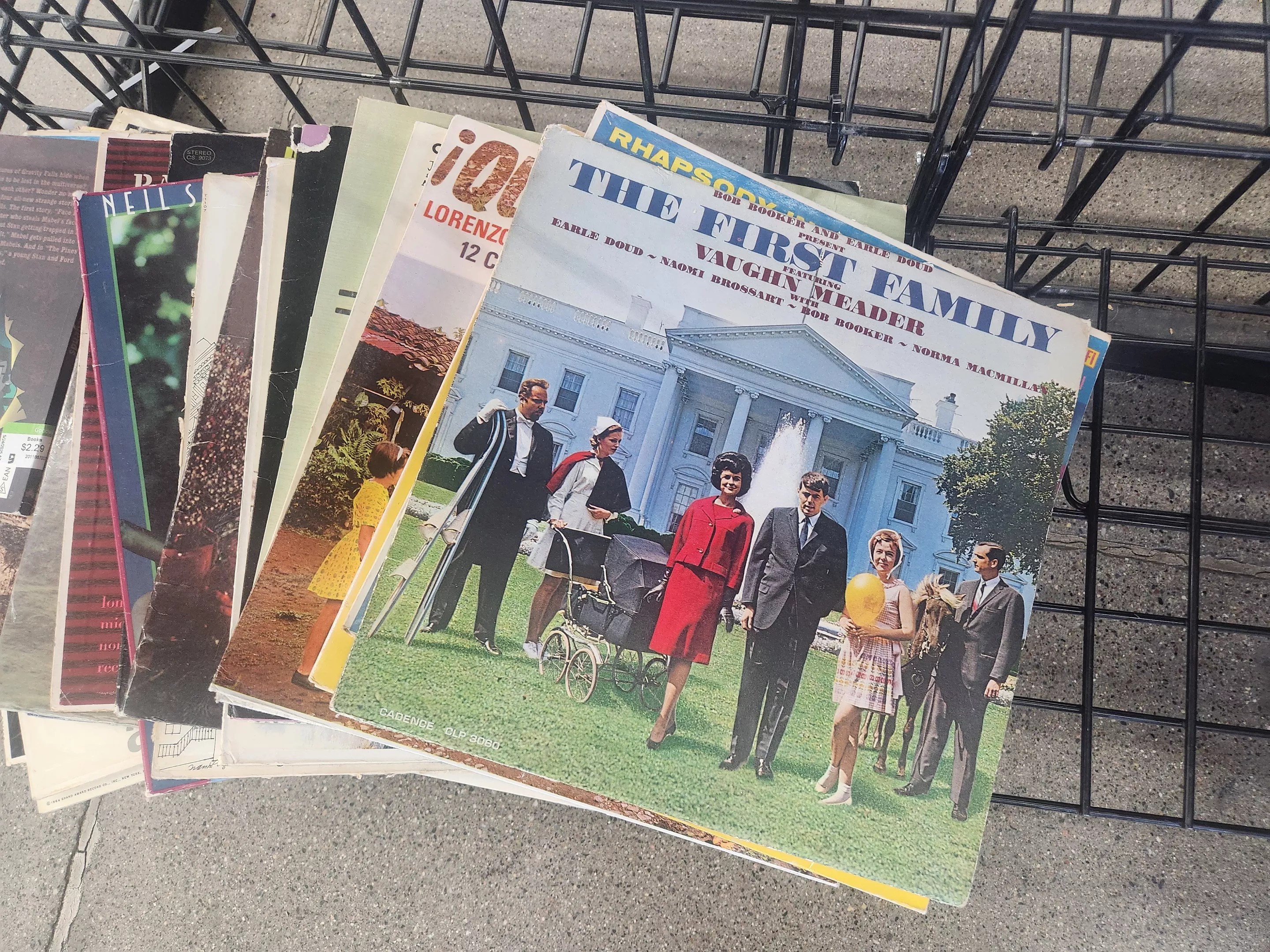

Despite being dead since 2004, Meader’s not hard to find. Walk into 40 random thrift stores, and he’s probably moldering in 30. His “The First Family” LP is a rack perennial with Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass’ “Whipped Cream & Other Delights” and the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s “Time Out” – and for at least one very logical reason.

In their time, all three records were huge. So they once were everywhere and now, in tangible dotage, needed to exist somewhere. Much of their original audience is gone, collections left to descendants, abandoned or surrendered.

“Time Out” achieved a milestone no jazz album before it had reached, selling 1 million copies and becoming a landmark LP in 1959, the year critics still consider a genre peak. “Cream” spent 140 weeks in the Billboard Top 40, eight at No. 1, in late 1965. Its iconic cover – Dolores Erickson in shaving suds – has been referenced, honored and lampooned for generations.

Unlike “The First Family,” they wield cultural cachet today, reissued and reupholstered ad infinitum. “Family’s” is largely forgotten, the painful artifact of an America that both once was and never could be.

Yet it was a real, very real phenomenon. Released in November 1962, it passed 2 million sales by the end of that month, 4 million by Jan. 10, 1963. It became, for a while, the fastest-selling album ever. A total of 7.5 million filled homes.

Label Cadence Records celebrated this feat in the Feb. 2 Billboard with 12 pages of congratulatory ads, boasting notes of gratitude from distribution firms and suppliers. Need was such that it tested everyone’s manufacturing mettle; New York’s Modern Album and Finishing Co. alone produced 3 million “First Family” record jackets.

Radio was key to the disc’s success, starting with Stan Z. Burns at New York’s WINS. He spun the whole works on-air beginning Monday, Nov. 12, creating instant consumer demand and rapidly sparking nationwide appetites. “In case anyone underestimates the power of radio,” Cadence head Archie Bleyer said, “I can tell him that it is the most important medium of all in exposing not only singles, but albums.”

So besotted, DeMain Record Sales founder Bob DeMain swooned about nominating Vaughn Meader for president of the United States in 1964. The enterprise was that successful.

But, again, who the hell’s Vaughn Meader?

The Voice is born

One thing’s for certain: Abbott Vaughn Meader was NOT gonna be president in 1964. For one, at 28, he’d be too young to run. Plus, America had a star already in 46-year-old John Fitzgerald Kennedy, first elected in 1960 and surely bound for a second term.

The Kennedys came from money. The Maine-born Meader knew jacksquat past a drowned millhand father and alcoholic waitress mother who sent him to relatives around Boston, then to a children’s home-hardly blueblood material. A plod through the young man’s curricula vitae drops him nowhere near the White House: teenage hillbilly radio and tiny-club troubadour crashing through restaurants and bowling alleys before finally announcing in-store deals over an S. Klein’s PA system. The U.S. Army drafted him out of high school in 1953.

About nine years later, now a comic, he was discovered by Buddy Allen, soon to be his manager, at some National Laugh Foundation soiree. Within weeks, Meader played a birthday party at Greenwich Village coffeehouse Phase 2, where he entertained for $40 to $45 a week. (Needless to say, his then-wife paid the bills.) Meader wrapped his act with an “impromptu” press conference featuring audience members as the Fifth Estate and himself as President John F. Kennedy.

Kennedy takes were big business in ’62. Water-cooler wags bent “Cuba” to “Cuber,” “vigor” to “vigah,” mimicking the presidential patois. But Meader seemed uniquely qualified for the task.

For one, he was a good-looking kid, hair coiffed in the familiar manner. Two, he hailed from the same-but-not-so-same Massachusetts, so he didn’t pull his voice past mild exaggeration. Others took it far beyond parody, the whole “Why’d you pahk yo-uh cah so fah from the bah” trip. “He talks the way everybody ought to talk,” Meader said of his subject, “the way I understand speech.”

The bit killed, and Allen gave him to television, specifically Irving Mansfield’s “CBS Talent Scouts,” on July 3, 1962. Ed Sullivan ate him up. New York’s Blue Angel fed him $450 a week. More importantly, he caught the attention of radio and TV writers Bob Booker and Earle Doud, then formulating a full record with the president as its comic centerpiece. Talk about kismet.

Granted, like most entertainers, Meader didn’t want to be defined by one trick, especially what he christened The Voice. It was fun, but he had other plans. Yet he hoped to ride this wave cautiously ’til it crested. You know: iron, strike, hot, ka-ching.

So Doud and Booker pulled Meader and ex-model/receptionist Naomi Brossart, whose Marilyn Monroe-esque breathiness captured First Lady Jackie Kennedy’s elegance, into their web and made a 27-minute demo to shop around.

Unfortunately, despite its potential, an album ribbing a U.S. leader wasn’t an easy pitch. Most labels (12 said no, by Booker’s estimation) wouldn’t touch it, fearful of Camelot retribution. Ten-foot poles were evoked.

Luckily, Archie Bleyer at Cadence Records spoke not of poles. Although what he heard was primitive and unfinished – and he understood his rivals’ reticence – he thought it could be shaped into something saleable.

“When I first heard the album,” he told Billboard in late 1962, “there were only a few demos of some skits and a script outlining the others. A lot of the sketches were unusable; some of them, as far as I was concerned, were not in good taste. … The album didn’t come to us ready to go. It required hard work by all concerned.”

With a final draft and commissioned cast, “The First Family” went down in a single take on Oct. 22, 1962, before 150 to 250 invited guests at Fine Recording, Inc., jammed into the old ballroom at Manhattan’s Great Northern Hotel.

The real JFK that night apprised the nation of the ongoing Cuban missile crisis. “Our goal,” he declared, “is not the victory of might, but the vindication of right.” His frivolous doppelganger, meanwhile, fielded post-dinner questions from his wife regarding his untouched greens. “Let me say this about that,” he began. “No. 1: In my opinion, the fault does not lie as much with the salad as it does with the dressing being used on the salad. Now, let me say I have nothing against the dairy industry. However, I would prefer that in the future, we stuck to coleslaw.”

Which pretty much reflects the record’s whole tone: safe, anodyne, president as TV dad, his family in familiar domestic scenarios.

Its political commentary is more quietly clever than barbed. “Economy Lunch” mines Nikita Kruschev’s 1960 United Nations shoe-pounding incident for laughs and turns Mao Tse-Tung into a condiment-related quip. “The Decision” briefly explores Kennedy’s annoyance with Vice President Lyndon Johnson (Johnson: “Ah’d like to say somethin’ if I might!” Kennedy: “Must you, Lyndon?”). Cuban dictator Fidel Castro becomes the “evil prince with the black beard” in an album-ending bedtime story for young Caroline Kennedy (Norma McMillan), with the president, of course, as the tall, handsome hero “with all the hair.”

“The First Family” not only captivated the nation but also went gold, spent 12 weeks at No. 1 and won two Grammys: Best Comedy Performance and Album of the Year.

Even better, the president himself reportedly enjoyed the spoof – well, kind of.

During a Nov. 27, 1962, White House dinner, he solicited guests’ opinions of the record, mentioning the “Relatively Speaking” bit, where Jackie complains about the ever-present abundance of Kennedys. Her husband allays her concerns, then addresses each family member by name: “Good night, Jackie; good night, Bobby; good night, Ethel,” and so on. “Is that how I sound?” he wondered. (Jackie, however, was not a fan. When her husband extended an invitation to the comedian, she withdrew it.)

Despite this attention, Meader was determined to make it on his own. “Right now, I’m stereotyped as an impersonator,” he said in January 1963. “But that’s only part of my act, as I hope everyone will soon find out.”

Who the hell was Vaughn Meader?

Oh, America. Get ready.

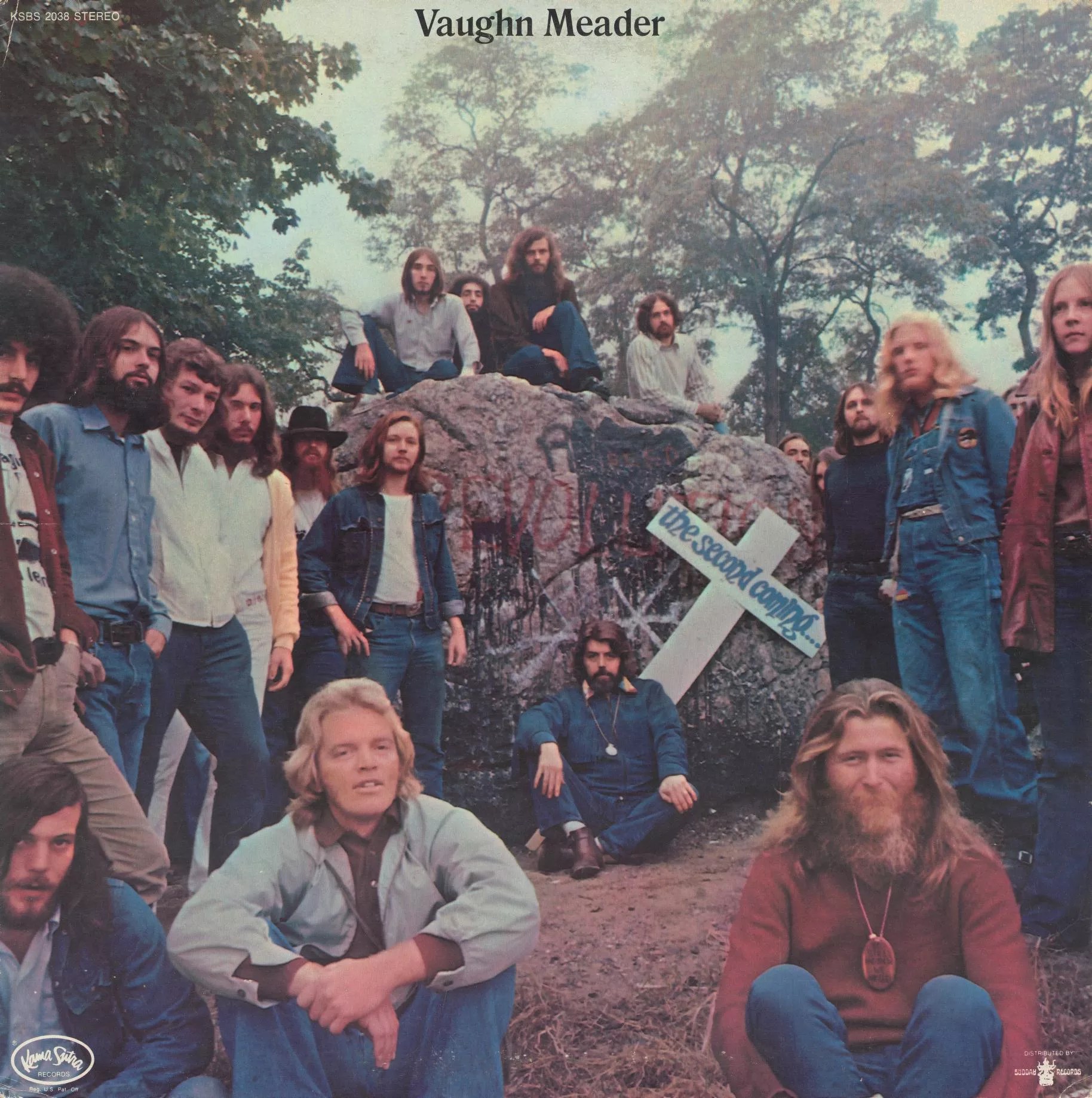

“Second Coming” cover.

Courtesy of Cory Frye

The Voice peaks

He could tell the papers whatever he wanted. Sadly, he was trapped between artistic pull and professional obligation. “The First Family” was hot, so of course, he and Brossart toured an ever-changing version (though he had space for his usual routine, too) from Carnegie Hall to a month-long shot at the Sahara in Vegas.

There was also the matter of his Cadence contract. Meader owed the label two albums, as Doud and Booker reminded him. New money didn’t make him suddenly independent. In fact, that’s what he was doing in cities across America: road-testing new material. Like it or not, he’d be The Voice on vinyl again.

Irritated, Meader entered New York’s Hotel Astor in March 1963 to rehearse what became “The First Family Volume Two.” His first act, Booker said, was to fling the script contemptuously – not exactly diplomatic tact.

However, the March 18 session at Columbia Recording Studios, this time a high-budget affair before a larger audience with a live orchestra, ran smoothly. In what seems like a concession to its star, the LP ends with Meader as himself interviewing schoolchildren on world affairs. “Do you know who I am?” he asks one tyke, who replies, “You’re not the president, but you’re the imitator.”

Released April 26, 1963, “Volume Two” sold well but nowhere near its predecessor. It peaked at No. 4 on Billboard’s Top LP chart. Reviews were friendly yet tepid.

That fall, Meader broke from Booker and Doud. Now at Verve/MGM, he sang and issued a folk dig called “No Hiding Place,” wrote and prepared a presidential farewell holiday 45, and began producing his first full-length non-Kennedy project. At last, he was on his own.

By then, it was November, time to strategize for the ’64 election. The incumbent’s overall chances were excellent, but he had to win Florida. Texas, too, where infighting plagued the Democrats. So Texas came first.

Kennedy arrived in San Antonio on Thursday, Nov. 21, then made his way to Houston and Fort Worth before beginning Friday morning in Dallas, traveling 10 miles from Love Field to a Trade Mart luncheon in a four-door 1961 Lincoln Continental convertible. All went according to schedule until multiple gunshots rattled Dealey Plaza.

It was 12:30 p.m. A half-hour later, the president was dead. A world fell into mournful shock.

Eight days after that, Lenny Bruce – hounded, doomed, dust in ’66 – gazed into a late-night New York chasm and sighed, “Wow! Boy! Sssssss! Poor Vaughn Meader!”

That poor, unfortunate son of a bitch.

Slowly going silent

There’s a story about how he got the news. Its poignancy is funny-sad, with the rhythm of a well-told joke.

New York, November 1963. Vaughn Meader hails a cab. Guy pulls up and says, “Hey, dja hear about President Kennedy?” “No,” Meader replies, “how does it go?”

Well, it went like this: He announced through Buddy Allen that The Voice was done. Two nightclub dates were canceled. That Christmas single never saw daylight. (If one pops up, you’ll pay better than thrift-shop prices.) Bob Booker called Archie Bleyer and told him to destroy every stray copy of those Cadence big sellers. Kennedy died in Dallas; the “First Family” LPs died in some New Jersey depot.

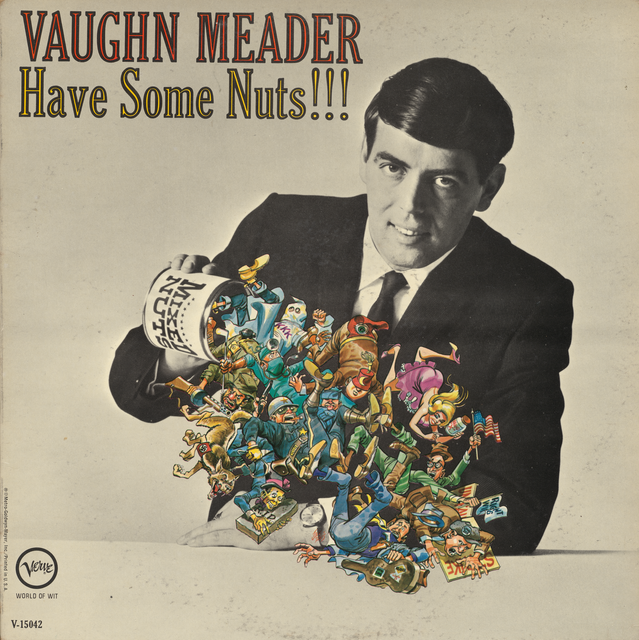

“Have Some Nuts!!!” – the record Meader completed before the assassination, his break from the JFK albatross – came out, followed by January 1965’s “Vaughn Meader Says ‘If the Shoe Fits … .'” Respectable notices, but neither made noise. “It’s a funny album,” Meader said of the latter, “but what does funny mean anymore, and who wants funny?”

Apparently, Verve/MGM didn’t and set him free.

Historically, the American public is no reliable barometer of “good” or “fair.” Yet it speaks with a silence that can’t be ignored. Kennedy once comprised but five minutes of Meader’s club act. It was meant to illustrate his quick thinking in character. Then it took ovah, his protests unacknowledged. So when the president went, the culture buried Abbott Vaughn Meader, too.

There were further efforts, sure: Laurie Records’ comedic “Take That! You No Good … ” in 1966, followed three years later by an extremely personal musical tour titled, of all things, “The Whatever Happened to Vaughn Meader Album” for the short-lived Nice label.

Reuniting with writer Earle Doud, who’d continued chasing the next “First Family” by skewering Lyndon Johnson and Spiro Agnew on vinyl, Meader released “Second Coming” on Buddah Records in late 1971. By then, he’d drowned his features in long hair and a beard as another martyr: Jesus Christ, returned to a then-modern universe unbathed in hippies, rock and TV.

No one cared. When reporter Rudy Maxa later phoned Billboard seeking the man’s whereabouts, an editor scraped his own recesses.

The Kennedy guy? I think he’s dead.

He wasn’t dead, just absent, surprisingly still a young man in his 30s. Yet he seemed long-lived, embracing religion, witchcraft and occultism, struggling with drugs and alcohol. Over time, he gave away his Grammy and went underground – i.e., northeast – focusing on music, releasing his own honky-tonk songs and performing wherever anyone felt like listening. He oversaw a club called The Wharf. There were morsels in films like “Lepke” and “Linda Lovelace for President” (both 1975).

Doud coaxed him back for another “First Family,” though strictly for nostalgia’s sake. This time, impressionist Rich Little starred as President Ronald Reagan, flanked by “Three’s Company’s” Jenilee Harrison, plus Melanie Chartoff and Michael Richards (yes, that one) of ABC’s “Fridays.”

The cover of 1981’s “The First Family Rides Again” is a knockoff of its forefather, albeit without Meader at its center or at all. Instead, he appears for six seconds in an “Integration” sketch as Attorney General William French Smith.

After that, minus the odd “Where are they now?” feature, he just, well, shut up.

“Have Some Nuts!!!” cover.

Courtesy of Cory Frye

‘That’s all I have left’

Nearly 31 years after his last Kennedy, Meader took The Voice for a final public spin. It was a Dirigo Players production called “The Return of the Word,” staged April 1-2, 1994, at Ashlie’s Ballroom, a former Key Bank, in Hallowell, Maine, where the man lived his remaining decades. Its scope was vast, covering the Garden of Eden to Calvary. Meader narrated in a Boston Irish Catholic timbre locals recognized on contact and assumed they’d never hear again.

“I resisted it for years,” Meader told reporter Lucky Clark. “I ran away. I didn’t want anything to do with it. I was haunted by it, and I just cut it off completely.”

History appears to have been kinder to “The First Family.” You can buy cheap copies like crazy, but both records also live in the more venerated Library of Congress, their master tapes at the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum in Boston.

Almost everyone involved with it is no longer here. That includes Bleyer, Doud, Booker, Norma MacMillan and Meader, who somehow got the last laugh in an interview made days before he mortal-coiled at age 68, forcing Lewiston, Maine’s Sun-Journal to run a Sunday feature as a Saturday dirge. His pepper-bearded visage gazed from an Oct. 30, 2004, front-page centerpiece.

“I let them have The Voice,” he said in parting. “That’s all I have left. So far, that isn’t gone. It’s right up here and can be bought for a song, a song, a song!”

So, finally: Who the hell was Vaughn Meader?

We’ll likely never know.