Steven Hsieh

Audio By Carbonatix

Josefa Ramirez of Venezuela first attempted to enter the United States as an asylum seeker at the Nogales port of entry back in January 2020. She had fled her home country with her 10-year-old son after she was allegedly detained, interrogated, and beaten by government officials.

But after being held in the United States for five days and deemed to have a credible asylum claim, Ramirez was sent back to Nogales, Mexico – a consequence of former President Donald Trump’s Migration Protection Protocols (MPP) policy, commonly referred to as the “Remain in Mexico” program. She has been in Mexico ever since, awaiting a court hearing that keeps getting rescheduled.

Recently, the new Biden administration announced that about 25,000 migrants caught up in the MPP program will be admitted to the U.S. while they are processed by immigration courts. Yet Ramirez and many others in similar situations are still in Mexico with no idea what will happen next.

Ramirez is currently living in Monterrey, Mexico, with her son, after spending most of 2020 in Nogales.

“I feel like I cannot make any plans. I feel tormented because I cannot move, I cannot do anything, I cannot plan my future, and all this uncertainty is killing me,” Ramirez told Phoenix New Times through a translator. “I’m hopeful but also frustrated because I have a date for a court but not an entrance to the U.S.”

Her case highlights the sluggish and confusing rollout of Biden’s effort to rebuild the U.S. asylum system after the Trump administration effectively ground it to a halt.

Immigration officials have recently begun admitting a small number of asylum seekers each day at select ports of entry in Texas and California, but Arizona remains closed off to asylum seekers in border cities like Nogales, Mexico where an estimated 200 to 400 MPP asylum seekers are living. Meanwhile, the Biden administration has yet to rescind the Trump-era public health order that allowed U.S. immigration officials to send illegal migrants and asylum seekers back to Mexico.

“As of right now, they’re waiting for some sort of clarity as to when they will be processed and where,” said Sara Ritchie, a spokesperson for the Kino Border Initiative, a binational aid organization that serves migrants on the Arizona-Mexico border. “No one that I know of that was returned to Nogales ever saw their court date. We have no idea what’s going to happen with them.”

Venezuela was in a state of crisis before Ramirez decided to head north to seek asylum. When widespread power outages rocked the nation in March 2019, she was working as a supervisor of technical and administrative personnel for a state-owned utility company. Government agents detained her and her colleagues and accused them of causing the black-outs, she said. They hit her on the head and tried to get her to accept responsibility for the failure.

“They asked me questions and they were seeking specific answers that I considered lies. They wanted us to answer in a way that I wasn’t willing to answer,” she said. “Some of my workmates were killed in custody.”

“Some of my workmates were killed in custody.” – Josefa Ramirez, Venezuelan asylum seeker

The experience left Ramirez shaken and “fearful” for her life, and she fled her job. After protests and civil unrest against Venezuela’s authoritarian president, Nicolás Maduro, continued to rock the country after the interrogation incident, she was hopeful that things might change. Ramirez ended up meeting with local legislators on a project to examine how to restructure the company and improve it. But she got word that former coworkers who were supporters of Maduro accused her of conspiring against the government, causing her to become even more scared.

In December 2019, Ramirez finally left Venezuela with her son to seek asylum in the United States due to political persecution. She hoped to join her husband, an asylum seeker who had already made it to Miami, Florida, with an older son. She decided to head to Nogales because she had heard from other Venezuelan friends who had crossed the border that the port of entry there was more organized than others.

The endeavor didn’t pan out the way she had hoped. The MPP program was already in place at that point. When she first arrived in Nogales, she had to put her name on the list that dictated who could be admitted by border officials to make their case for asylum on any given day. Eventually, on January 23, 2020, she finally entered the United States and was detained for five days. Immigration officials conducted a “credible fear” interview to assess the legitimacy of her case for asylum. Her claim was deemed credible, but she was sent back to Mexico to wait for her court date.

The news was devastating.

“They said that I had to go back to wait for a judge appointment in Mexico,” Ramirez said. “I didn’t want to return to Mexico. I didn’t know anybody or know what to do. I was in a lot of fear.”

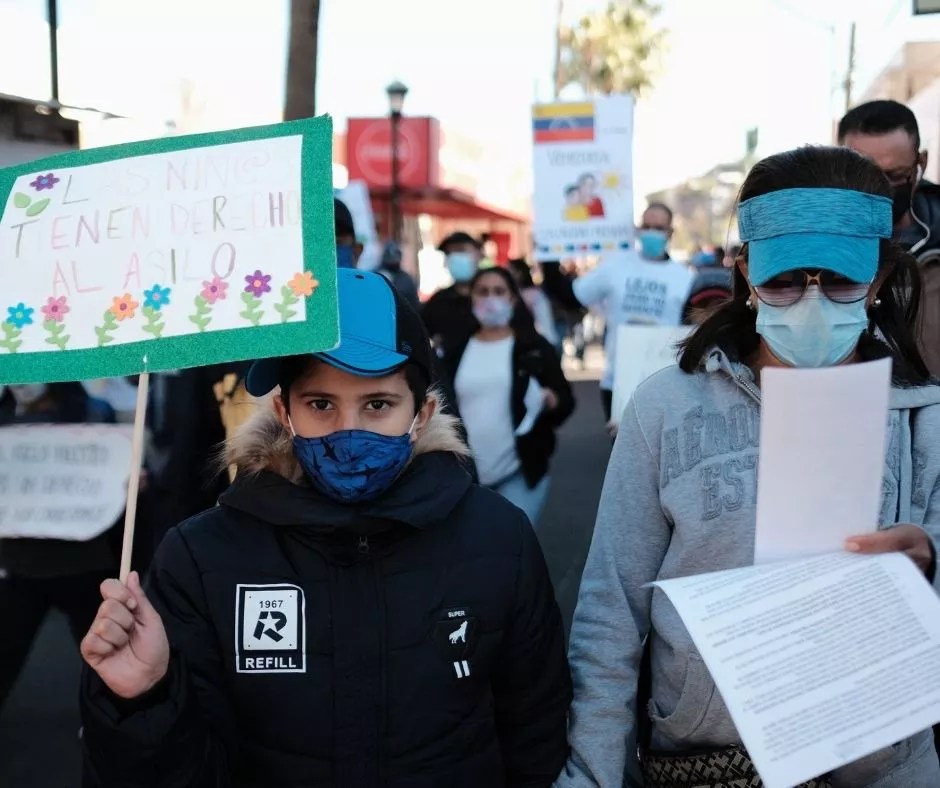

Josefa Ramirez, right, walks with her son during a SaveAsylum march along the border wall in Nogales, Sonora on December 2, 2020.

Photo courtesy the Kino Border Initiative

Like so many other asylum seekers who ended up stranded in Mexican border towns as a result of the policy, Ramirez spent the next year or so in Nogales. She got food from local humanitarian service providers and eventually was able to secure an apartment using money that her husband had sent her. As the months went on, she felt vulnerable as a migrant woman living alone in Mexico with a child. Men frequently made indecent proposals to her on the street and she feared that her son, who was bullied at a local school for being a migrant, would be kidnapped.

At one point, her husband received a phone call from men who demanded ransom money, claiming that Ramirez had been kidnapped. He was about to send the money before Venezuelan friends were able to contact Ramirez and confirm that she was ok.

The hardships faced by some migrants due to MPP have been well-documented. According to a January 2021 report by Human Rights Watch, asylum seekers in MPP who were sent back to cities like Matamoros along the Texas border were subjected to frequent kidnappings (sometimes of children), murder, rape, and assault. Squalid migrant camps developed in some border cities, though not in Nogales.

“Being sent back to Mexico is being told to wait in one of the circles of Hell for an indefinite period of time before you hear about whether you can get asylum,” said Josiah Heyman, a professor of anthropology at the University of Texas at El Paso who specializes in border issues. “These Mexican border cities are remarkably dangerous. I know the ones in Sonora are not as dangerous as the rest of the border – not for good reasons but because they’re controlled by the Sinaloa [Cartel] – but the homicide statistics in Mexican border cities are horrifying.”

Ramirez and her son later moved to Monterrey to stay with a Venezuelan friend who recently had a baby. The deal was that she would help them with the newborn child in exchange for not paying rent. The city feels safer to her than Nogales. (Crime rates, however, are reportedly higher in Monterrey than in Nogales.)

Finally, she got a phone call from a staffer with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) who told her that she would be admitted to the United States due to Biden’s changes to the MPP program. The caller needed to verify basic information like her passport number and whether she has had a recent COVID-19 test. The staffer told her to “stay put” in Monterrey and wait for a second phone call.

The United Nations was brought in by the “U.S. and Mexican governments” to help run some of the logistics for the changes in the MPP program, according to Chris Boian, a spokesperson for the UNHCR.

“UNHCR is working with locating and registering individuals who were enrolled in the MPP program,” he said.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM), another United Nations agency, will be conducting COVID-19 tests of MPP enrollees at “staging locations” in Tijuana, Matamoros, and Ciudad Juárez 24 hours prior to their scheduled date of entry to the U.S., according to IOM spokespersons Rahma Gamil Soliman and Alberto Cabezas Talavero. The agency will then transport people with negative test results to the border for entry. Those who test positive will remain in “isolation facilities” for 10 days before entry.

Currently, the U.S. is only admitting MPP enrollees into San Diego, California, and El Paso and Brownsville in Texas. With Nogales not admitting asylum seekers, this means that the hundreds of MPP enrollees who are living there will have to eventually head east to cross the border.

“We’re assuming, and also worried that they’re going to say that all that were returned to Nogales are going to have to go to Juárez,” said Ritchie with Kino Border Initiative. “There has not been any announcement that there would be a process on the Arizona-Mexico border.”

Spokespersons representing U.S. Customs and Border Protection, the Executive Office for Immigration Review, and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services did not respond to questions regarding the government’s rationale for not admitting asylum seekers in Arizona or potential future plans regarding local ports of entry.

At a White House press conference on March 1, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas blamed the Trump administration for the delays in rebooting the U.S. immigration and asylum system.

“Quite frankly, the entire system was gutted,” he said. “What we are seeing now at the border is the immediate result of the dismantlement of the system and the time that it takes to rebuild it virtually from scratch.”

For local immigration advocates, the Biden administration’s timeline isn’t fast enough.

“The fact that this is moving so slowly really makes us worried for the phases to come that are necessary to be able to fully restore the asylum system,” Ritchie said. “Those with active MPP cases are just a small sliver of the asylum-seeking population that has been denied due process.”

Ramirez’ next court date is on June 23 in El Paso. Since she was recently contacted by UNHCR staff, she’s hopeful that she can finally leave Mexico and enter the United States. But Ramirez is simultaneously “frustrated” since she has a new court date but no confirmed date for entry. She calls the court date a “fictitious date” because “nothing is for sure.”

“I want have a clear path with certain dates,” she said. “I’m not even seeking the American dream. I’m just seeking safety for me and my children and my family.”