Morgan Fischer

Audio By Carbonatix

It looked like court. It sounded like court. But it was not quite court — technically.

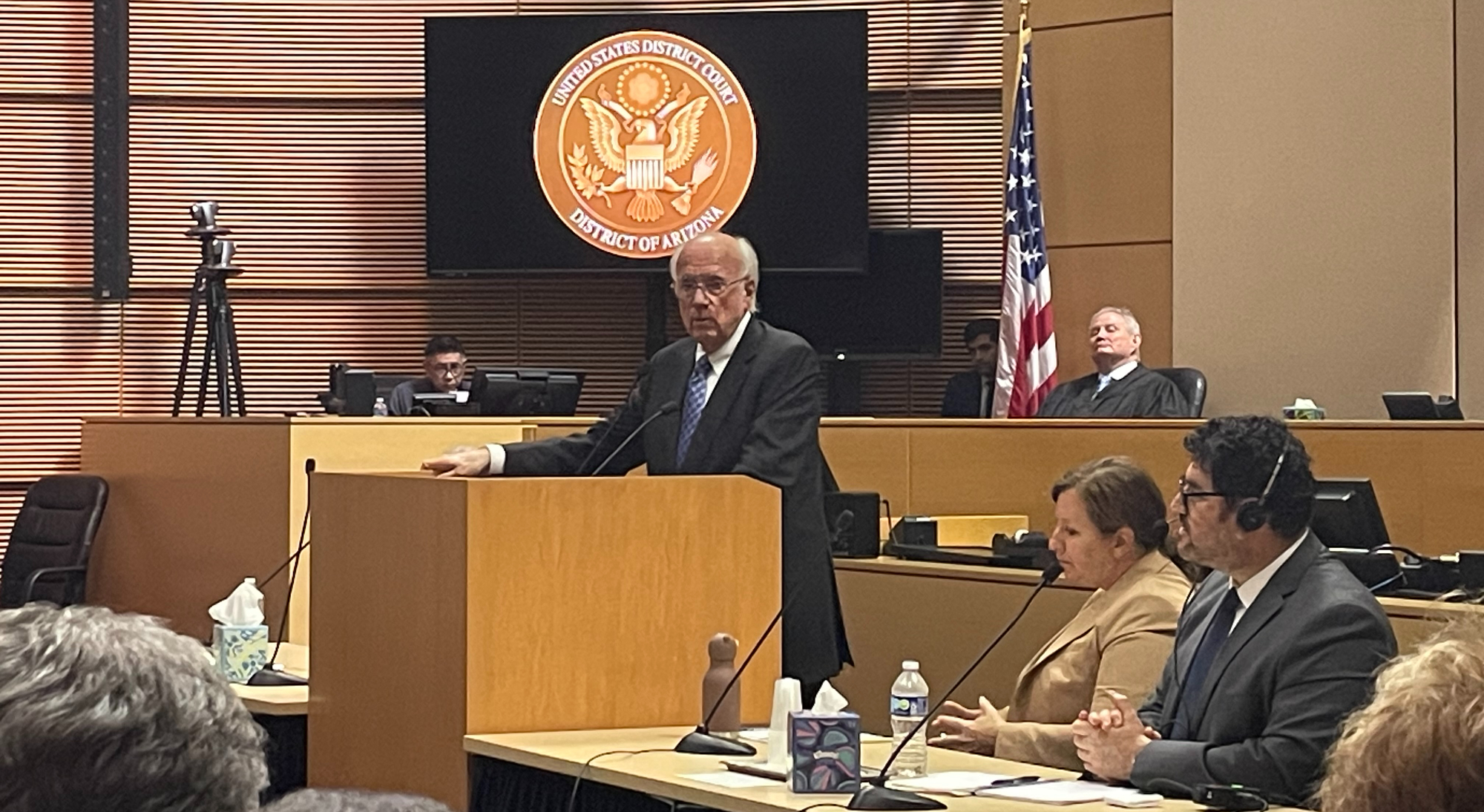

Wednesday evening, federal Judge G. Murray Snow sat below the United States seal in the circular special proceedings courtroom at the Sandra Day O’Connor U.S. Courthouse in Phoenix. He wore a black judicial robe, though he issued no rulings from his perch. Snow was there to preside over — and keep the lid on — a community meeting with the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office that had lately been getting out of hand.

The meetings have occurred four times a year for more than a decade because Snow has required them to. In 2013, Snow ruled in Melendres v. Arpaio that the sheriff’s office had racially profiled Latino residents during the reign of former Sheriff Joe Arpaio, who used his office to instill fear in Hispanic communities under the guise of immigration enforcement. Since that time, Snow has required the sheriff’s office to make certain reforms, and the sheriff — there have been four of them — has been required to meet with community members once a quarter alongside court-appointed monitor Robert Warshaw to discuss the agency’s progress.

Most recently, however, the meetings had gotten too rowdy for Snow’s liking. At the July meeting in Maryvale, pro-sheriff Republicans packed the meeting, upset about the estimated $350 million in taxpayer dollars spent on compliance since the case began. Those attendees clashed with the largely Latino residents who usually attend the meetings. Heckling was rampant and local politicians engaged in grandstanding. Two attendees got pushy with another. A pro-sheriff supporter told a critic to “go back to Mexico.”

Snow had planned to attend that meeting, but he decided against it after Warshaw told him that some attendees were armed. In response, Snow decided to drastically change the meeting’s format, moving it from a rotating series of community locations to the federal courthouse. And instead of it being structured like a shaggy free-for-all, Snow would preside over it and keep order.

Wednesday’s meeting was the first of that new regime. Like a high school teacher reining in a crowded room of troublesome students, Snow began the meeting with a stern and detailed history lesson of the Melendres case as a presentation was played on the courtroom’s TV screens. The courtroom was packed with mostly pro-sheriff attendees, while more people — mostly Latino community members — filled an overflow room in the basement.

Snow’s presentation began with his 2011 preliminary injunction that ordered the sheriff’s office to stop engaging in racial profiling — an order the Arpaio-led agency openly flouted. Attendees sat silently as Snow walked them through the case’s history, including how sheriff’s deputies kept inmates’ belongings as personal souvenirs. He outlined his orders, how the sheriff’s office needs to achieve “main and effective compliance” for three years before being released from those orders and where the agency was still falling short.

The sheriff’s office has made significant progress but still isn’t in complete compliance with any of Snow’s four orders. Most notably, the agency still hasn’t cleared its backlog of complaints made to its Professional Standards Bureau.

After Snow’s history lesson, Community Advisory Board members Raul Piña and Michael Nowakowski spoke, as did lawyers from the ACLU and the county. Current Sheriff Jerry Sheridan also spoke and expressed great confidence in his department to engage in constitutional policing, although he made something of a Freudian slip.

“There is no one on the planet, as much as me, who wants my deputies to be biased,” Sheridan told the crowd before correcting himself. “Unbiased. No one, next to the court, wants unbiased policing more than me.”

Zach Buchanan

All out of time

Some found Snow’s lecture useful.

“Those people who were there tonight got the history lesson behind why it has to happen,” said People First Project founder Clarissa Vela, who also attended the previous meeting that went “haywire.” Piña, the chair of the advisory board, felt Snow’s remarks got everyone “up to speed.”

“I think it was an important overview of the case,” he said. “I’m glad the public got the chance to hear that.”

But while Snow may have imposed order over the meeting, there was little opportunity for residents to express themselves, as some community activists worried would be the case under the new format. That included residents concerned about the ongoing costs of the case, though that subject was raised by Snow.

Earlier this month, Snow issued a report from Warshaw’s monitor team that included an audit of the county’s compliance expenses. Far from the runaway train of costs, the monitor found that the sheriff’s office had overstated the price tag of following Snow’s orders by $163 million. Expenses loosely related or completely unrelated to the case — including purchases like golf carts, car washes and jet fuel — were chalked up to compliance in Melendres. By doing so, the audit suggested, the county was able to circumvent state laws limiting budgetary spending.

Sheridan has questioned the audit’s accounting without rebutting any of the specifics. In a ruling issued Tuesday, Snow gave the sheriff’s office the opportunity to respond to that report, though he noted that he’d already “given them the opportunity” and they “have not provided their justification.” The audit did not include the roughly $34 million the county has spent funding the monitor’s activities or the county’s attorneys’ fees in the case, though Snow pointed out that Maricopa County’s high attorneys’ costs are something the county has “chosen” for itself by fighting the case.

“This is not an easy case. It is an expensive case,” Snow said. “It is a case where everybody in Maricopa County has benefited, whether or not they appreciated it.”

Warshaw, who has been the focus of criticism by county officials, took a similar lecturing approach to Snow as he introduced his monitoring team, almost all of whom have a background in policing. In layman’s terms, he tried to explain the importance of emptying the PSB backlog, comparing it to getting bad customer service at Walmart. Warshaw also called on the audience to “lower the temperature. Lower the rhetoric. It is not helping.”

By the time the question-and-answer portion of the evening arrived, only about 30 minutes remained in the meeting’s allotted time. Instead of opening the microphone to attendees, the CAB had collected questions from the community in a Google Doc to read on their behalf. Piña asked questions about the audit. Sheridan responded that he “vehemently disagreed” with it but didn’t know how the much-repeated $350 million number came about. Nowakowski shared community questions about Immigration and Customs Enforcement workplace raids and the makeup of the monitoring team.

But quickly, it was 8:30 p.m., when the meeting had to end. Several people yelled from the crowd when time was up, including Republican Arizona Attorney General candidate Rodney Glassman, a Sheridan ally. “Your Honor, how is it that you can be so polite to all of us and the federal monitor can be so condescending?” Glassman called out. After the meeting, Glassman told Phoenix New Times that he felt Warshaw was “talking down to everyone in the room” and spoke “arrogantly.”

Another woman tried to ask Snow to start the next meeting “with the prayer and the pledge,” but court staff quickly began ushering everyone out of the packed courtroom, down the steps and out of the building entirely.

“I really hope you all come back next time and we will answer them,” Snow told the crowd about their questions. “I apologize that it didn’t happen this evening.”