Goodyear Police Department

Audio By Carbonatix

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include comments from Goodyear police sketch artist Mike Bonasera.

***

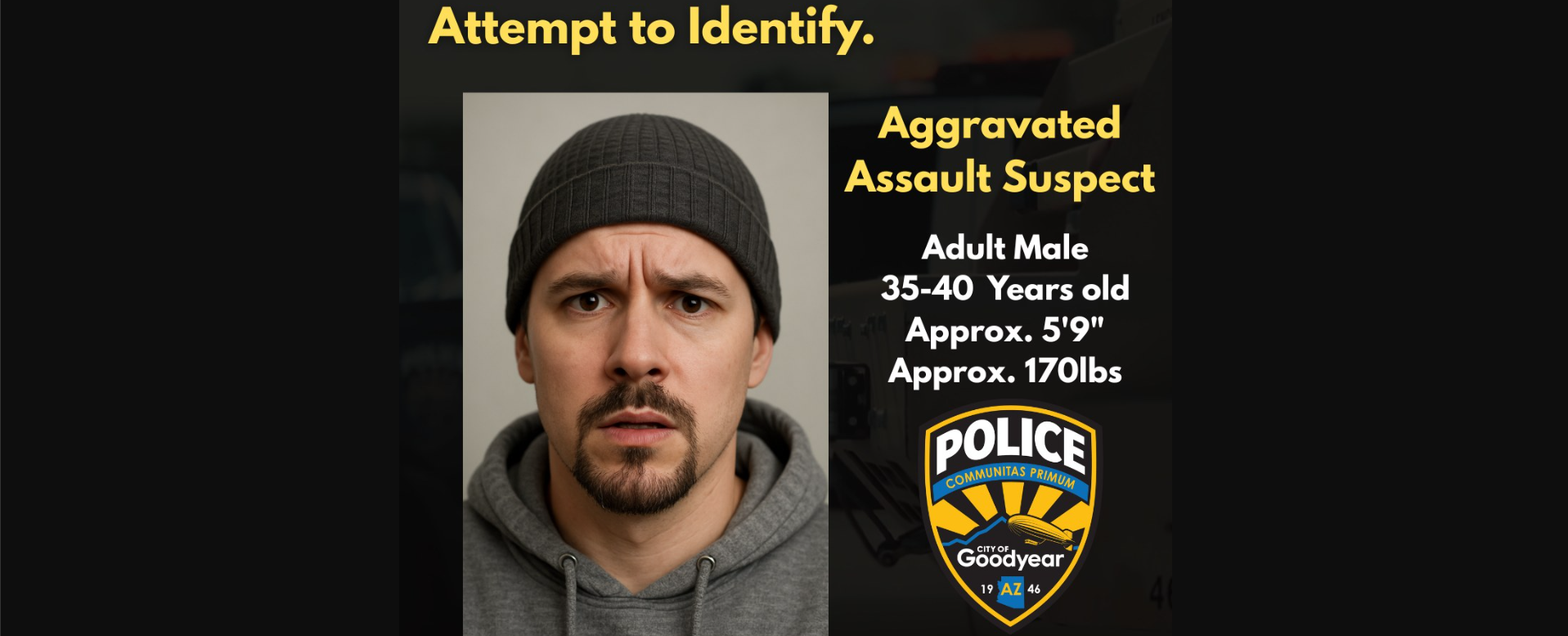

On Friday, the Goodyear Police Department posted on its social media accounts that its officers were looking for a man who fired a gunshot near 143rd and Clarendon avenues. Included was a remarkably clear picture of the man.

The image wasn’t a real photo or even an artist’s rendering, at least not in the usual sense. Instead, the suspect picture distributed by the department was generated by artificial intelligence.

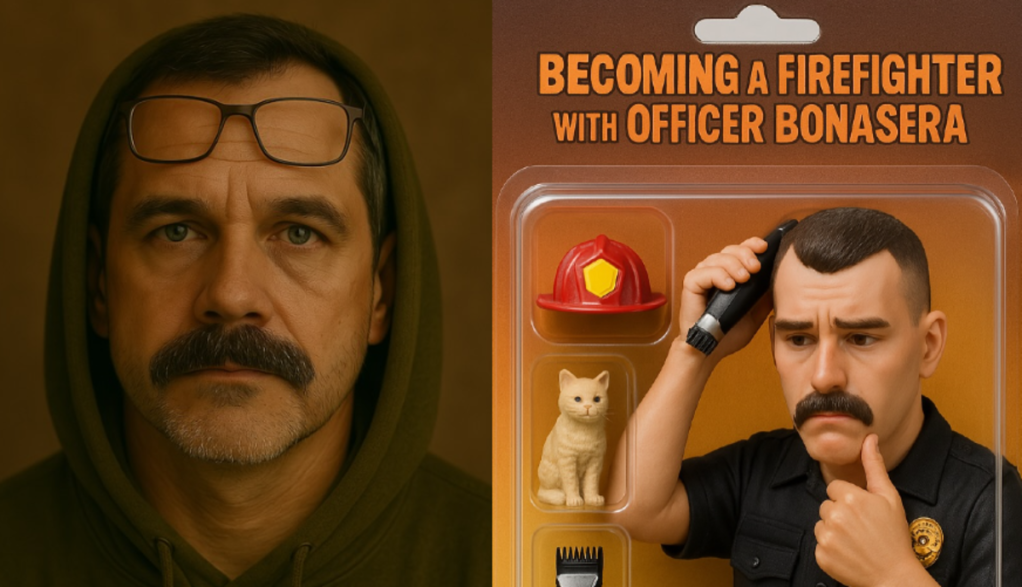

The “sketch” is the second one the West Valley department has produced with AI this year. The first time was back in April, when police posted a similar photo of a mustachioed man in a hoodie with a pair of clear glasses over his forehead. It purported to capture the appearance of a suspect accused of grabbing a young female student — who managed to escape — while she was walking near Village Boulevard and Watkins Street.

Goodyear police spokesperson Sgt. Mayra Reeson confirmed to Phoenix New Times that these are the only two instances in which the department’s sketch artist, officer Mike Bonasera, has used an AI tool to develop a photorealistic sketch.

“The artist still conducts the full interview and hand draws the sketch based on the witness description,” Reeson said in an email. “The only difference is that they now use AI, including tools like ChatGPT, to enhance the final image so it appears more realistic. It does not replace the traditional process; it just sharpens the final product.”

Goodyear appears to be alone among the nation’s police departments in using AI to develop photo-realistic sketches of suspects. In a phone interview, Bonasera told New Times that he and the department’s deputy chief tested the technology by creating AI-enhanced sketches for suspects who had been caught and arrested. He described the results as “astonishing.”

“Once we started doing all these tests, the chief saw it and was like, ‘Holy moly, this is amazing,’” Bonasera said. The department checked with County Attorney Rachel Mitchell to see if her office would be OK with the use of the technology for prosecution; she was reportedly “very excited” about it, Bonasera said.

After the first AI-enhanced sketch was shared, Bonasera was invited to speak on a panel at an International Association for Identification’s conference, where he learned that law enforcement agencies in other countries have created sketches with similar tools.

“I actually learned that they’ve been using this kind of technology overseas for decades, but it’s not as advanced as the technologies we have,” he said, citing England and Japan as examples. But those techniques, he said, created faces using stock features — like blonde hair or blue eyes — from a small library.

“You still need the artist, and the artist has to create this drawing because the drawing is what is going to make your AI rendition more accurate,” Bonasera said.

Goodyear Police Department

Unanswered questions

Reeson said no arrests have been made related to either AI-enhanced sketch — both of which contain a disclaimer that the image is AI-generated and “does not depict a real person” — so the effectiveness of the new practice is unclear. But some AI and policing experts wonder if it’s effective at all.

The use of AI in creating sketches is all part of a larger trend in policing, said Brandon Garrett, a professor at Duke University School of Law and faculty director of the school’s Wilson Center for Science and Justice.

“Just like we’re all getting AI add-ons on our phones that we didn’t ask for,” he said, “law enforcement is getting all kinds of AI applications marketed to them regularly, as well as AI add-ons to things they already had.”

The problem with many AI tools, though, is that they don’t work nearly as well as the marketing copy suggests. Nathan Wessler, a deputy project director with the ACLU, noted the growing adoption of the Axon software Draft One, which uses AI to assist officers in writing police reports — and which he said is “almost certain to introduce errors.”

AI-enchanced police sketches bring similar drawbacks. That includes both a risk of wrongful arrest and prosecution and not solving crimes because “police go running off in the wrong direction.”

“This is an extremely novel use of AI that raises, for me, a lot of unanswered questions,” Wessler said. “If they’re just trying it out based on no validation studies, no reason to think that this is an acceptable and trustworthy way to try to identify a subject, then they’re putting people at risk.”

Both Wessler and Garrett noted that the realistic nature of an AI sketch may give people the wrong idea about how much is known about the suspect’s appearance. “One good thing about a sketch is it’s sketchy — and that may be the best we can get from someone’s memory of an unfamiliar person they saw,” Garrett said. Nothing about it conveys certainty.

An AI sketch may be just as imprecise but lead people to believe otherwise. Suspect identification is already a fraught process with plenty of room for error — research has shown that people have a difficult time remembering the faces of strangers — and that’s without adding AI on top of it.

Bonasera says he has debated the subject extensively and sees the point.

“I totally understand. A drawing is going to give you a little bit more of the question of what’s unknown,” he said. “It’s always the victim or witness’s drawing at the end of the day. All I need to hear them say is, ‘That’s the person,’ and that’s it.”

Bonasera said that the department received hundreds of messages related to the April sketch — far more than normal sketches usually arouse. “It was overwhelming for our detectives. Usually, when you just put out a sketch, people tend to not really engage with it as much,” he said. “It’s making people look.”

But Wessler said that while people take a hand-drawn sketch “with a grain of salt,” a photo-realistic image is not going to give people that kind of pause and so may result in overconfidence by members of the public.” The actual suspect could possess few features that an AI sketch reinforces, but a completely innocent person could.

The Goodyear Police Department already amusingly illustrated this issue. One day before the department posted its first AI sketch — of a white man with a thick brown mustache — it posted AI-generated action figures of several Goodyear cops. One was Bonasera, the officer who hand-draws police sketches.

The two AI images shared a notable resemblance:

Goodyear Police Department

Bonasera, despite chuckling and admitting it was funny, wasn’t so sure about the resemblance.

“I don’t see it,” he said, clarifying that he was not the suspect.

Not the worst thing

In the grand scheme of things, this use of AI is not necessarily the most unreliable application of the technology in policing. Garrett said there are bigger concerns regarding generating images of faces from DNA samples, as the company Parabon is doing.

“At least here it’s an image based on someone’s visual memory,” Garrett said. “There are a lot of concerns about that, but at least you aren’t trying to generate a picture with something else.”

Other uses of AI include police departments using Draft One for police reports and putting sketches into a facial recognition technology program to look for a possible match. The latter is “very much not how that technology works,” Wessler said. “There are several levels of errors baked in there, so you have a real high likelihood of false identification there.”

Goodyear’s use of AI may bear more resemblance to the intrusion of AI in other avenues, like search engines. They’re attempting to serve the same purpose — creating an image of a suspect, returning an answer from the internet — only slightly warped and less reliable.

As AI images get more photorealistic — but not necessarily more accurate — discerning what to trust is going to be a challenge. Doubly so when a suspected criminal is on the loose.

“If it generates an image that is way off, people are going to notice it. That’s not the problem,” Wessler said. “The problem is going to be that it generates an image with six subtle differences, which in aggregate makes a big difference.

“But that’s very hard for a normal human to suss out.”