Courtesy of Romanucci & Blandin

Audio By Carbonatix

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to include comments from a press release issued by the legal team behind the lawsuit and with a response from Glendale.

***

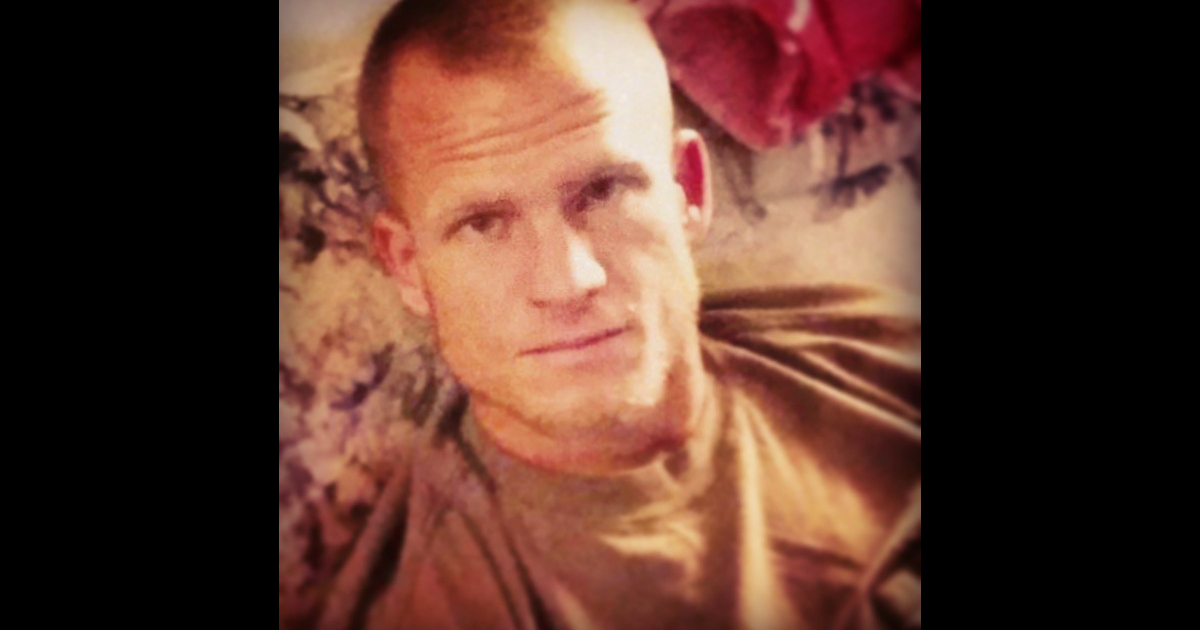

One evening in early 2025, Glendale police descended upon Horizon Park near North 47th Avenue and West Butler Drive. They were on the hunt for Angelo Diaz, a 23-year-old domestic violence suspect. Instead, they found and fatally shot 46-year-old Dillon Siebeck, an uninvolved bystander.

Siebeck’s death on Jan. 8, 2025, generated outrage at the time and calls for transparency as the shooting was investigated. Now, his brother and mother — Arliss Siebeck and Helen Domme — are suing the city and two of the cops involved in the shooting for carelessly taking Siebeck from them.

On New Year’s Eve, the pair filed a wrongful death suit in the United States District Court for the State of Arizona. According to the suit, Siebeck’s relatives “now seek some measure of justice on behalf of Mr. Siebeck, who was unlawfully and unjustifiably killed by an officer of the Glendale Police Department who was entrusted to protect the public.”

The suit names the city, officer Juan Gonzales and his supervisor, Sgt. Joshua Anderkin, as defendants. Glendale spokesperson Jose Santiago said the city could not comment on the lawsuit, but did say the department fired Gonzales in December after two reviews — by a “Response to Resistance” board and a Citizen’s Review panel — found the “shooting was outside of policy and keeping him as public safety officer could potentially be a safety risk to our community.” Anderkin remains on the force, Santiago added.

The lawsuit also accuses Gonzales of excessive force and unlawful seizure, faults Anderkin for failure to intervene and supervise, accuses both cops of failure to render aid and holds the city liable for the police’s constitutional violations.

“The wrongful death of Dillon Siebeck is, unfortunately, a textbook example of excessive force violations by police,” said attorney Antonio Romanucci of Romanucci & Blandin, which is representing Siebeck’s family in the case, in a press release. “This man was unarmed and did not present any type of threat to the officers. He was not a suspect in a crime and was minding his own business. Dillon’s loss of life was completely needless. We will pursue full accountability for what happened that evening in Glendale.”

Romanucci’s firm previously called for Glendale police to release all relevant body camera footage of the incident.

“Siebeck did not display any weapon, and he made no verbal or physical threats to any individual,” the lawsuit states. “Officer Gonzales had no justification for shooting at Dillon, who posed no threat to any person or property. Officer Gonzales could not have reasonably perceived that Dillon was a threat to any person or property at the time he fired, as Dillon was hundreds of feet away, was unarmed, was not displaying or in possession of any weapon, and made no physical or verbal threats to any officer or any other person.”

ABC15 reported that Siebeck, who was from Tucson, was a father and Army veteran who’d struggled with mental health issues. The station reported that Siebeck had been released from an Arizona prison nine days earlier.

“Dillon loved to make people laugh and would literally do anything for the people he cared about,” said Arliss Siebeck in the press release. “Our family deeply misses his huge heart, and his death has changed us forever. What upsets us is that what happened to Dillon could happen to anyone. It could have been anyone in the park at that time, and unfortunately, it was my brother. We sincerely hope this lawsuit can bring transparency and accountability for his loss, but also can create change for the community so no family ever has to go through this again.”

Manny Marko / Creative Commons

‘Good man, good man’

The tragic chain of events was set off by a hunt for Diaz.

Per the suit, cops found a white pickup truck that matched the description of Diaz’s vehicle and instructed anyone inside to exit the vehicle with hands raised. When no one answered, the cops noted that there could be someone hiding inside before they “inexplicably shifted their attention” away from the vehicle to Siebeck, who was sitting on a picnic table 100 yards away.

The lawsuit notes that Siebeck bore little resemblance to the description of the suspect sought by police.

“Unlike GPD’s suspect, Dillon was 46 years old — twice the age of the man they were looking for,” the lawsuit says. “Unlike GPD’s suspect, Dillon was not Hispanic.”

The suit says Gonzales pointed an assault rifle at Siebeck and several other officers pointed their guns toward the man. Using a PA system, Anderkin instructed “Angelo” to walk toward the officers with his hands up. The suit claims Siebeck complied, prompting Anderkin to say, “Good man, good man.”

At the time, Glendale police claimed Siebeck “made a movement towards his waistband,” though the lawsuit filed by Siebeck’s relatives does not directly address that allegation. “Dillon was unarmed. Dillon at no point displayed or possessed any weapon. Dillon made no verbal or physical threats to anyone or any property at any time,” it states, adding that there was no one else in the vicinity.

While Anderkin told Siebeck — whom he again called “Angelo” — to keep his hands on his head, the suit says, Gonzales fired two shots with the assault rifle without giving any warning that he was going to shoot. There was no attempt to use less-lethal weapons. “After the shots and that instruction,” the suit says, “there is a 14 second pause in which no further instructions are given by any GPD officer.”

Gonzales then fired two more shots, with at least one striking Siebeck, who went down. The suit says he remained on the ground for nearly 20 minutes before any life-saving aid was offered.

According to the suit, Anderkin said, “Suspect down,” and added that police would “need the dog to get this guy.” Anderkin allegedly did not order any officers to provide medical care or radio for medics until 15 minutes after Siebeck was shot — a delay that the suit claims Anderkin “knew or should have known” would mean likely death. It wasn’t until 19 minutes after Siebeck was shot that officers approached him, taking one minute and 15 seconds to cover the distance between them, the lawsuit claims.

Eventually, the officers finally looked inside Diaz’s vehicle and found Diaz dead from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

The Peoria Police Department was tasked with investigating the incident. In a statement to New Times on Tuesday, the department said that in February, it forwarded the case to the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office, which determined in April that there was “no reasonable likelihood of conviction.”

Gage Skidmore/Flickr/CC BY-SA 2.0

A history of excessive force

At the time of the shooting, state Sen. Analise Ortiz demanded accountability.

“Anytime a police officer shoots and kills someone, there needs to be full transparency and a thorough investigation,” Ortiz, whose district includes Horizon Park, told New Times last year. “In this case, the fact that this person who was shot and killed was not even the person that police were after is absolutely horrifying.”

To New Times and in a press release, Ortiz highlighted the larger issue of policing in the Valley and the United States.

“This pattern of police shooting first and asking questions later is a common pattern that we see, and in this case, it ended up being deadly for an innocent person,” Ortiz told New Times. “There needs to be accountability and there needs to be answers. My constituents use the park and enjoy the park. Nobody should have to fear that when they’re out and about, a police officer is just going to rush up on them and take their lives.”

About two years before Siebeck was killed, Glendale police shot and killed a 15-year-old, prompting calls for more transparency. Ortiz said a year ago that she was in contact with the boy’s family, who faced challenges getting clear answers from the police department, noting that a common factor in police killings is that “families are shut out of the process.”

Ortiz did not immediately respond on Tuesday when New Times asked for comment on the lawsuit.

The lawsuit also details Glendale police’s “documented pattern and practice” of excessive force, naming at least nine incidents in which Glendale cops used what it claims was unjustified and unnecessarily violent tactics. It also alleges that the city has failed to hold its officers accountable for such behavior.

The incidents it lists include a February 2015 shooting in which an officer shot a man who was raising his hands, a 2016 incident in which an officer fired 15 times and killed a suspect’s twin brother and officer Matthew Schneider’s tasing of Johnny Wheatcroft in the genitals in 2017 for improperly using a turn signal. The lawsuit claims that “Schneider had been disciplined by the City of Glendale at least six times yet was permitted to retain his police powers.”

An April 2019 report noted that the city had paid $3.6 million in settlements during the previous five years, though not all were related to police misconduct claims. The city has settled at least two other cases since then (including Wheatcroft’s), but the amounts of those settlements were not made public.