Image by TA2YO4NORI/Getty Images, illustration by Eric Torres

Audio By Carbonatix

Those pushing for a controversial new AI data center in Chandler — a cohort that includes paid not-technically-a-lobbyist Kyrsten Sinema — have made big promises about how it would save the city water.

Razing an existing structure to make way for the new one will instantly save 12 million gallons as if flicking a switch, according to the project’s developer, New York-based firm Active Infrastructure. The data center, located at the 40-acre Price Innovation Campus near Price and Dobson roads, will also use a fancy closed-loop cooling system, significantly reducing its water consumption compared to similar facilities. As Arizona approaches a water crisis — with dwindling groundwater supplies and looming cuts to its Colorado River allotment — the pitch sounded almost too good to be true.

Well, about that…

The final development agreement, which is up for a vote by the Chandler City Council on Thursday, tells a different story. Namely, the agreement and internal city emails obtained by Phoenix New Times via a public records request show that the data center development — which consists of the center itself and five planned additional buildings — could suck much more water out of Chandler’s pipes over the long run than is being used at the site currently.

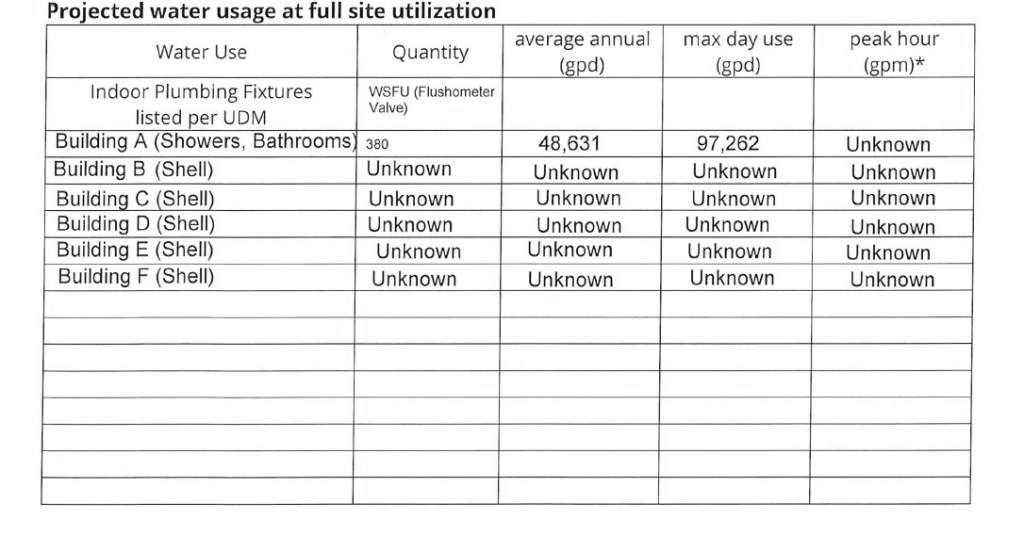

According to the agreement, the data center would be approved to use an average of 48,631 gallons of water a day. That’s roughly 17.75 million gallons a year, more than 5 million above what is currently used by an empty office building presently on the lot. Additionally, city emails show that Active Infrastructure revised those numbers downward — from an average daily usage that would have come out to 21.6 million gallons a year — after the city said it was too high to be approved.

The emails also show that Active Infrastructure initially suggested that the five additional buildings, which could theoretically house clients of the data center, would each use as much as 52,752 gallons of water a day. Together, that would add up to more than 96 million gallons of water a year.

Those numbers have been stripped out of the draft agreement that will go before the council, however. Now, the additional buildings are listed with a water usage that is “unknown.” However, both Active Infrastructure and city staffers say what’s on paper about the data center’s water usage is not necessarily what will happen in practice.

In an October presentation before the Chandler Planning and Zoning Commission, the company’s local zoning attorney, Adam Baugh, told commissioners that the lot’s vacant building, which would be demolished, has been “burning more than a million gallons a month annually” because its cooling system must be maintained for insurance purposes. The moment Active Infrastructure shuts down the building’s antiquated cooling system, Baugh said, “I instantly return to the city about 12 million gallons of water savings each year going forward.” The company made a similar claim in an August email to the city, stating that “we do not anticipate utilizing close to the 1 million gallons of water per month that the vacant building was utilizing.”

But at least on paper, the development agreement would allow Active Infrastructure to use much more than that once the data center is built. And that’s not to say what would happen if the additional five buildings are put up.

“They’re not going to save 12 million gallons if they build these other buildings,” said Rick Heumann, a former Chandler city councilmember who chairs the planning commission, and the only commissioner to vote against sending the development agreement to the city council. “They’re going to use a lot of water.”

Asked for comment, Active Infrastructure stated in an email to New Times that “the numbers contained in the Sustainable Water Service Application were per the City’s direction and do not represent the actual anticipated usage of the building.” The statement also said the numbers on the application were based on the use of a larger water meter, a device that measures the flow of water into a building.

“Given our commitment to use water for only domestic fixtures, as evidenced by our closed-loop cooling system that does not require the on-going use of water, we anticipate our daily water consumption to be significantly less than what is shown on the application,” the statement read.

The known unknown

It is true that the city advised Active Infrastructure on how to best complete the water use application.

In emails obtained by New Times, city water manager Simone Kjolsrud informed Active Infrastructure CEO Jeff Zygler in August that the company’s previous estimates of water usage for the data center building were too large to meet the city’s requirements for the building’s water allocation. Kjolsrud referred to a previous water use application by Active Infrastructure, which estimated that the average daily water use for the data center would be 59,136 gallons per day, or 21.584 million gallons a year.

Zygler had two options if he wanted the application to dovetail with the city’s regulations, Kjolsrud told him: Either reduce the building’s average daily water use estimate to 48,631 gallons and the max to a figure less than 100,000, or request a higher water use allotment, which would “take several months and would require council approval.”

Active Infrastructure’s earlier application also estimated water usage for the other five buildings. Each could use 52,752 gallons per day on average. One of those buildings will be built at the same time as the data center, but the rest are considered speculative by both the city and Active Infrastructure. Kjolsrud advised Zygler that since the potential tenants and water use for the buildings were unknown, entries for those buildings should be listed as “unknown.”

Kjolsrud told New Times that the daily water use figures on the water service application were standard for the category of building that Active Infrastructure wanted to erect. She thinks the first application was simply a screw-up. “I can’t speak for what was in their mind, but in my opinion, their original application was probably just not accurate,” Kjolsrud said. “It was them not understanding the instructions of the application.”

Kjolsrud said that the development agreement requires Active Infrastructure to utilize a closed-loop cooling system, which uses “far less than 48,000 gallons per day.” Active Infrastructure could go over that limit at peak times, as long as its daily average, per year, remains at or below 48,631 gallons.

The water usage for the other buildings is listed as “unknown” because no tenants have been identified for them yet. “It’s impossible to provide an accurate projection of water use,” she said, because “they don’t know what’s going to be happening in them.”

Chandler’s economic development director, Micah Miranda, said that if Active Infrastructure used more water than allotted, in violation of its development agreement, the city could pursue civil penalties. But he said that in general, “everybody gets into voluntary compliance because they do not want to lose water access.”

Still, the “unknown” label on the five speculative buildings is no consolation to Sandy Bahr, director of the Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon Chapter. Even if Zygler is correct that his data center will consume only a fraction of the water other data centers use, Bahr said that doesn’t include the water used to generate the 150 megawatts of electricity the data center has been approved to receive from SRP. The utility’s energy pie is 72% nonrenewables — coal, gas and nuclear — which are all water-intensive energy generation sources, Bahr said.

That’s a lot of water spent on a low-employment data center at a time when Arizona cities face up to 20% cuts in water from the Colorado River — and as Chandler encourages its citizens to voluntarily conserve water.

“It seems like they should be thinking about conserving water across the board,” Bahr said. “There are types of projects that use a lot less water and provide more jobs than a data center.”

Growing opposition

The proliferation of data centers has drawn significant backlash nationally. Datacentermap.com, a site used by both media and industry professionals, shows that Arizona currently hosts 164 data centers in three markets, with the majority located in the metro Phoenix area. Overall, the site lists 4,266 data centers for all 50 states, indicative of the data center gold rush that AI has helped create.

Chandler already has an ordinance on the books limiting the construction of new data centers in the city, which is awash with them. Aside from Sinema’s stultifying performance while shilling for the data center in front of city officials, the potential noise created by the data center, its rapacious need for energy and the paucity of jobs created by such behemoths are a few of the reasons Chandler residents have come out against the project.

Emails obtained by New Times also show that Active Infrastructure’s zoning attorney attempted to dismiss certain criticisms of the project in correspondence with city staffers. The opposition emails — which outnumbered those in support by a 10-to-1 margin — were forwarded to Baugh by city staff. Baugh kvetched about some of them, nitpicking their validity.

Baugh complained that four separate “no” emails “appear to be two husbands and wives,” as if married individuals should count only as a unit when it comes to public opinion. He also complained about three emails “from the same household,” and another from someone who lives “7 miles away.”

“Are we really going to accept this letter as opposed? Doesn’t really seem fair to me,” Baugh asked about one emailer from Gilbert, which is just east of Chandler. Of course, the fight for water resources is a zero-sum game, meaning the more Chandler uses, the less there is for Gilbert or anyone else.

As more and more Chandler residents emailed their disapproval — many of them inspired by Sinema’s mid-October threat to the city that President Donald Trump may force the data center on them anyway — Baugh’s cavils subsided. But his correspondence with city staffers did get tense at points.

In one email from August, Chandler’s development director complained to Baugh that someone at an Active Infrastructure-hosted community meeting phoned to tell him that “it was publicly stated that I am supportive of the project, site plan and phasing.” Miranda reminded Baugh that he had not taken a position on the proposal, “as numerous issues still need to be resolved.”

Baugh shot back a response, denying the claim and telling Miranda, “I know who called you” and that Baugh’s comments at the meeting had been misrepresented. In reply, Miranda restated that his department had not taken a position and was presently neutral. Baugh answered Miranda with near-palpable angst.

“I don’t want to overreact, but when I see people stirring the pot and creating unnecessary controversy, it’s hard not to pick up the phone and call BS on them,” Baugh wrote. Later in the email, Baugh seemed to unintentionally land on exactly what the opposition emails wanted. “I don’t know what else I could do short of abandoning the AI data center,” he wrote.

Of course, Active Infrastructure’s data center plan also proved unpopular with Chandler city staff, which advised the planning and zoning commission to reject it. The commission instead voted 5-1 to advance the plan to the city council. But first, emails show, the city tried to extract a price in return.

Chandler initially suggested that Active Infrastructure sell the site’s 40-acre property to the city for $1. The municipality also asked that the company donate $300,000 over the course of three years to the Chandler Education Foundation for a scholarship to “support the workforce needs of the purported AI related employers at the site.”

Baugh rejected both ideas as nonstarters, writing to Miranda that it was inappropriate “to compel the developer” to gift the land to the city or donate the money. The subject, apparently, did not come up again.

Absent those promises, the city council seems primed to vote for the data center anyway.

If it’s approved, the riddle of how much water the completed project will use will ultimately be answered. Years from now, after the data center comes online, the other buildings are completed and they all start drinking from the city’s pipes, Chandler residents will all find out together.

This story is part of the Arizona Watchdog Project, a yearlong reporting effort led by New Times and supported by the Trace Foundation, in partnership with Deep South Today.