Photo Illustration by Eric Torres. Getty Images/Adobe Stock Photo

Audio By Carbonatix

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story misidentified the judge overseeing Juanita’s case. The judge was Judge Pro Tempore Alexia Sedillo, not Judge Leonore Driggs. Phoenix New Times regrets the error.

***

The week of Thanksgiving, 67-year-old Phoenix resident Juanita sat at the end of the third pew in the downtown Phoenix Arcadia Biltmore Justice Court, engulfed in nervous anticipation. She clutched her small beige purse as she stared straight ahead, listening to Judge Pro Tempore Alexia Sedillo call the cases of defendant after defendant.

In a few minutes, she’d learn if her family still had a place to live.

Just days earlier, Juanita received an eviction notice on the front door of her two-bedroom detached apartment in which she’s lived for seven years. Inside, the space is cramped. Juanita shares a bed with her daughter, while her sister, who is disabled and can’t work, sleeps in the other bedroom.

Juanita, who asked that her last name not be used to protect her privacy, isn’t alone. Through November, there have been 79,858 eviction filings this year in Maricopa County, which is on track to break a record set in 2005. Thirteen out of every 100 renters in Phoenix have had eviction proceedings brought against them, according to Princeton University’s Eviction Lab. Only two major cities – New York and Houston – have seen more eviction filings than Phoenix.

In Arizona, the problem continues to grow. The number of eviction filings has increased since the COVID-19 pandemic, and Maricopa County just missed breaking its eviction record last year. The causes of the crises are myriad: Arizona’s low housing stock and especially its lack of affordable housing, rapidly rising rents, stagnant wages and inequities in the court system all contribute. The pandemic exacerbated every single one of them.

“The numbers are going up, and they’re tragically high right now, but it’s been pretty bad for a long time,” said Drew Schaffer, the executive director of the William E. Morris Institute for Justice, which focuses on protecting the rights of low-income Arizonans.

In the Valley, the crisis plays out daily in the county’s 26 Justice Courts. Month after month, thousands of residents pile into courtrooms and videoconference rooms hoping to keep a roof over their heads and keep the constable at bay. Often, they have no one to help them through the process.

Just as often, their landlords win.

This year, Maricopa County is on pace to break its 2005 record of 83,687 eviction filings.

Katya Schwenk

A worsening crisis

It wasn’t always this bad. From 1990 to 2024, household incomes in Phoenix increased by 90%, but that significantly lags behind home prices – they’ve ballooned by a whopping 432% over the same period, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Now Phoenix is a hotspot for housing unaffordability. The Arizona Department of Housing says the state is about 270,000 homes short of what it needs to meet demand. Two-thirds of that housing gap specifically affects low-income renters – per the Arizona Research Center for Equity and Sustainability, the state is more than 183,000 affordable housing units short.

With low supply and high demand, rents have unsurprisingly skyrocketed, rising nearly 72% over the last decade. Today, the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Phoenix is $1,328 a month. To afford that – meaning to spend no more than 30% of one’s income on housing – tenants must make $53,112 per year, according to Apartments.com.

Here’s the problem: In Phoenix, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, roughly 30% of households make less than $50,000 a year. In fact, nearly half of renters cannot comfortably afford their rent. These tenants are “cost-burdened,” with many spending between 50% to 80% of their income on rent instead of the recommended 30%.

“The rents are too high for families and households to be able to sustain,” Schaffer said. “They’re spending a disproportionate amount of their resources on rent and housing costs. And that’s why, when they have a temporary financial emergency, they end up facing eviction.”

But for one small twist of fate, Catherine Wilkins knows that could be her. The 65-year-old pays $1,080 a month to rent a West Phoenix studio apartment. A back injury prevents her from working, so she lives off of her monthly $1,400 disability check. That means more than 77% of her income goes to housing.

Despite living in a low-income senior housing complex, Wilkins has seen her rent continue to rise while her disability check never gets any bigger. Plenty of renters are in a similar position. While incomes in Phoenix did rise by 32% from 2010 to 2022, rents rose by more than double that amount during the same period.

That puts tenants in a precarious spot, squeezing costs to make ends meet. To cut costs, Wilkins often seeks meals at a local food bank. She’s stopped buying meat because she can no longer afford it. For a money-strapped renter, one disaster could quickly lead to eviction. If a child gets sick, a car is totaled or a job is lost, the homes could be next.

“It’s a mess for us out there,” Wilkins said. “And I’m not the only one who goes through this.”

So far, Wilkins has avoided an eviction notice, but Juanita has not been so fortunate. Like Wilkins, Juanita badly hurt her back in an accident. She needs trigger point injections and is unable to work. Her social security hasn’t kicked in yet, leaving her without a source of income and unable to pay rent for the last three months.

As she awaited her name to be called in court, she owed $4,424.25 in unpaid rent, utilities and late fees.

“When it rains,” she said, “it pours.”

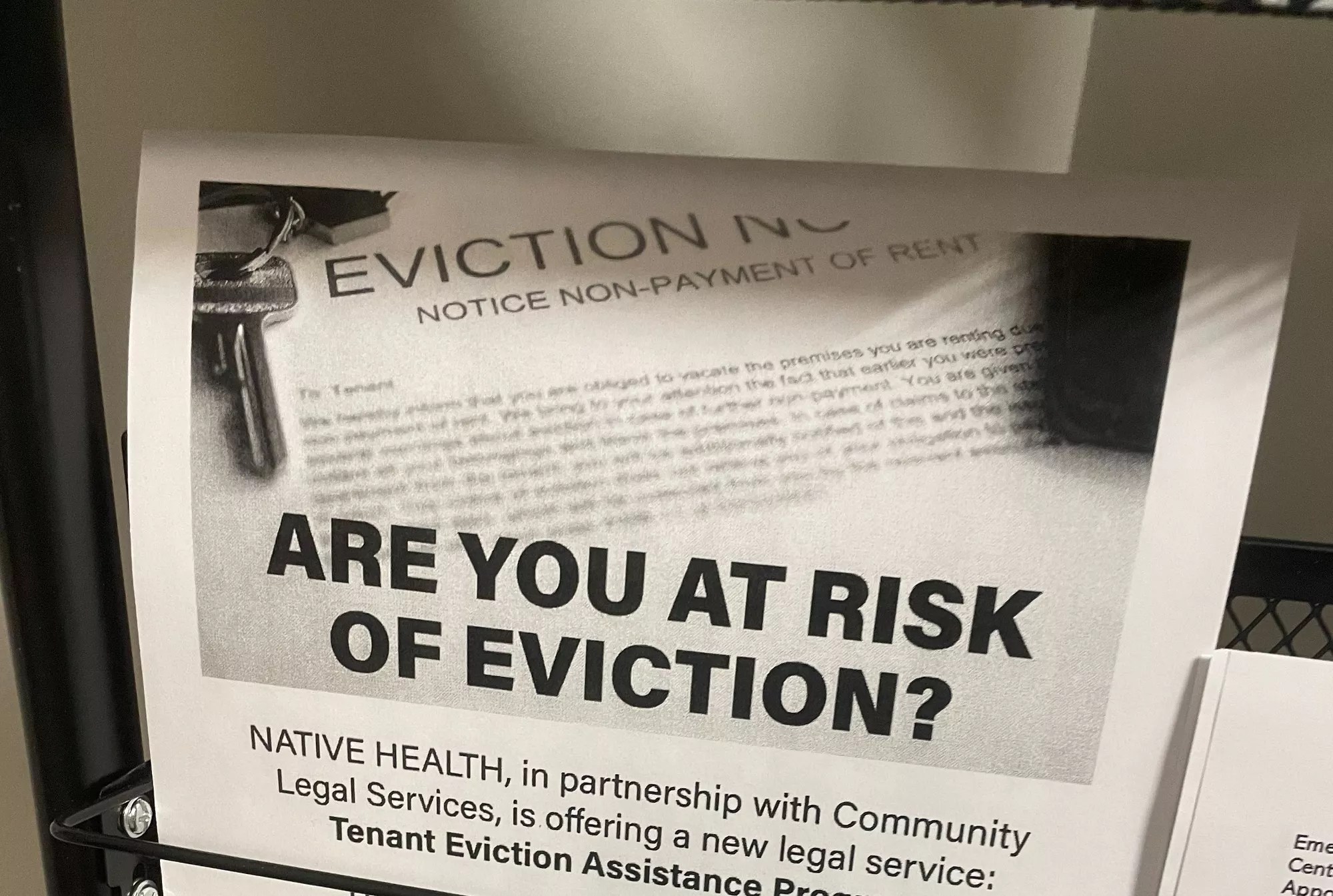

A flyer on display at the Phoenix Municipal Court’s Community Justice Resource Center.

Morgan Fischer

‘I still live in fear’

As she waited to hear her name, Juanita held on to the smallest glimmer of hope.

Not every eviction filing results in an eviction. But in the eviction process and even before it, almost all of the power resides with the landlord. For low-income renters, the threat of eviction constantly looms. When a notice does appear, it begins a two- to three-week legal process that can be incredibly stressful for tenants.

Evictions themselves don’t tell the whole story, which is why the Eviction Lab looks at filings rather than judgments. Though Arizona Multihousing Association spokesperson David Leibowitz said about a third of filings are settled outside of court, Eviction Lab research specialist Grace Hartley says informal evictions – those occurring through a substantial rent increase or threats by landlords – also are common. Eviction Lab estimates that for every one formal eviction, two informal evictions occur.

“Even if someone is not necessarily being evicted by a sheriff, people are still being displaced,” Hartley said. “Simply filing against someone is a very stressful and traumatic event that leads to a lot of negative outcomes, both financially and in terms of health.”

Two and a half years ago, Wilkins experienced an informal eviction. She was living in a Peoria apartment complex and paying about $800 a month. But each year, her rent increased. Soon, the same apartment cost Wilkins $1,400 a month, which she couldn’t afford. Instead of trying to scrape by and face eviction, Wilkins left to live with her daughter.

“I felt like I was being bullied out,” she said. “I came very, very close to being evicted. I still live in fear of that today.”

Wilkins had somewhere else to go, but many others do not. They stay in their lease but start missing payments, hoping to scrape things together in time to stave off homelessness. When they don’t, they find themselves in eviction court.

Unsurprisingly, Maricopa County’s homelessness problem and evictions problem share root causes.

According to Pam Bridge, the director of advocacy and litigation for the nonprofit law firm Community Legal Services, 80% of tenants in court wind up there after they received a five-day eviction notice for failure to pay rent. In those situations, Arizona is hardly atypical – per the legal site Nolo, 52% of states give tenants five days or less to pay up after an eviction notice. Experts say the entire process, from notice to suitcases on the curb, can take as little as two to three weeks.

Eviction court can be a busy place, although it may not appear so at first glance. On the day of her hearing, Juanita was one of four people in the Arcadia Biltmore Justice courtroom. The other three were Judge Sedillo, a court staffer and one other tenant facing eviction. The rest of the packed docket was filled by people joining the proceedings virtually.

The Arcadia Biltmore Justice Court covers central and East Phoenix and is the fifth-busiest of Maricopa County’s justice courts, according to court data. More than 320 evictions were filed in the precinct in November and the court has seen 3,870 filings so far this year.

As Sedillo called the names of plaintiffs and defendants, almost all of the landlords were represented by Colin Clark from Clark & Walker P.C., who attended court via Zoom. (Clark declined to comment for this story.) By contrast, many tenants didn’t attend the hearing at all, and none of those who did – by Zoom or in person – had legal representation. Only a few had a way of paying their outstanding balances.

As Juanita waited her turn, tenant after tenant spelled out the circumstances that brought them to court. One man – who was awoken for court by his mother on Zoom, an interaction that was broadcast in the courtroom – begged for understanding as he explained that a series of personal and family situations had left him unable to pay rent.

Another woman joined the Zoom call from her car and explained that she had just moved from Oregon after escaping a domestic violence situation. Her apartment was crawling with bugs, and her landlord wouldn’t accept third-party payment from organizations who were trying to get her back on her feet.

Circumstances such as pest infestation would have been grounds for a claim under Arizona’s Residential Landlord and Tenant Act. But now, it was too late. Because eviction proceedings are considered a simple breach of contract instead of a loss of home and safety, Sedillo couldn’t consider those factors. In both cases, she ruled in favor of the landlord, setting a date for when a constable would remove both residents.

If the woman had acted earlier, Sedillo informed her, the Landlord and Tenant Act may have protected her.

“I don’t know the law,” the woman responded.

Few tenants have anyone to call upon who does.

State Sen. Anna Hernandez won a Phoenix City Council seat while advocating for a right-to-counsel program for people facing eviction.

TJ L’Heureux

‘An unfair process’

Like every other tenant in court that day, Juanita did not have a lawyer. Legal resources for tenants facing eviction are available, but there aren’t enough of them.

Community Legal Services offers representation for low-income tenants for civil proceedings, with a staff of about 25 attorneys and paralegals who prioritize cases through a triage system. Ones with a legitimate defense, such as a landlord failing to make necessary repairs, go to the top of the list. CLS also negotiates with landlords to give tenants more time to pay.

The organization has a Tenant Eviction Assistance Project that helps tenants regardless of income. It’s funded in part by Phoenix and Maricopa County, though the city funding will run out at the end of December. Other services, such as rental assistance programs, are sparse at best as the state no longer funds them “to any significant degree,” Schaffer said.

CLS’s goal is to keep an eviction off a tenant’s record, even if it means negotiating an out-of-court solution. An eviction record can lead to loss of housing vouchers and damaged credit and can even make it more difficult to secure a job. Unfortunately, the majority of tenants walk into court with no lawyer.

In Maricopa County, 94% of landlords have legal representation in court, while only 0.2% of tenants do, according to a 2020 study by the Morris Institute for Justice. That imbalance has clear consequences: 76% of eviction cases studied by MIJ resulted in judgments in favor of the landlord, while only 5% were dismissed.

“If no one’s there in the courtroom to ensure that your rights are being upheld, and the landlord does have an attorney, it’s already an unfair process,” said Sebastian Del Portillo, the Arizona campaign manager for the labor group Organized Power in Numbers.

OPIN wants to change this inequality. Over the past two years, the group has been speaking with members of the Phoenix City Council and city departments about a starting right-to-counsel program, which would expand free legal representation in civil court to a wider net of tenants. Specifically, OPIN wants Phoenix to pass a recurring line item in the city budget to provide $2 million toward a program to hire and train attorneys and connect tenants with these services.

In January, former Councilmember Yassamin Ansari spoke in favor of the program. She noted that cities with similar programs have saved millions of dollars annually and seen evictions drop by 77%, which she said would have equated to 64,000 fewer evictions than Phoenix saw in 2023. Over the past four years, 17 cities – including New York City, San Francisco and Philadelphia – plus five states and two counties have enacted a right-to-counsel law for tenants facing eviction, according to the National Coalition for a Civil Right to Counsel.

OPIN needs five “Yes” votes to pass such a program. After the election of Councilmember-elect Anna Hernandez, who will take over the seat Ansari vacated to run for Congress, Del Portillo feels “pretty damn close” to getting them. Hernandez, who won in a landslide victory, campaigned on the need for a right-to-counsel law. While in the Arizona Senate, Hernandez also successfully sponsored a bill that aims to increase the housing stock by legalizing accessory dwelling units, or casitas, in certain municipalities.

“This is going to be the immediate, tangible way to make sure that people are staying in their homes,” Hernandez said. “We gotta address the root causes.”

Del Portillo and Hernandez believe Councilmembers Laura Pastor, Betty Guardado, Kesha Hodge Washington and interim Councilmember Carlos Galindo-Elvira, who will be leaving Hernandez’s city council seat in April, would support this program. Washington and Galindo-Elvira have spoken out in favor of right to counsel, while Pastor gave a statement to New Times that focused on education instead. Guardado did not respond to a request for comment.

If all four support a right-to-counsel program, that leaves one more vote to secure from either Mayor Kate Gallego or Councilmembers Kevin Robinson, Debra Stark, Ann O’Brien and Jim Waring.

“We really have an opportunity to definitely push the conversation much further with Anna Hernandez and try to get it up to a vote,” Del Portillo said.

But that won’t happen for months, if it happens at all. In the meantime, evictions continue to rise. In court, Juanita’s name was about to be called.

‘Can you pay?’

Roughly 45 minutes into the 9 a.m. proceedings, Sedillo summoned Juanita. Representing her landlord, Clark explained how much Juanita owed.

“Do you owe this rent?” Sedillo asked her.

“Yes,” Juanita responded.

“Can you pay it?” Sedillo asked.

“The money isn’t on me,” she said, searching through her purse. “But I can today.”

Sedillo motioned Juanita to approach the bench and explained that she would hold off on making a judgment until 4:30 p.m. that day. Juanita would have until then to make a verified payment, through cashier check or money order, to her apartment complex. Otherwise, Sedillo would sign the judgment and put Juanita one step closer to eviction.

Juanita signaled that she understood. She’d make the payment.

As she exited the courtroom, Juanita was confident but rattled. She said her husband of 40 years, who had been in Texas for the last six months caring for a sister fighting cancer, was coming back into town. He’d be able to help.

“If I didn’t know the money was coming, I would have panicked,” she said. “My husband has the money, so we’re just going to pay it all out.” The idea of emptying their home on such short notice seemed an impossible task. “We have so much stuff,” she said. “We can’t get it out soon.”

But the 4:30 p.m. deadline passed, and Juanita had not submitted a payment. Sedillo signed the judgment in favor of the landlord, setting a date, less than two weeks from her first eviction notice, for her family to vacate the apartment. If they didn’t, a constable would remove them.

That date came earlier this month. On Dec. 1 – as Arizonans shopped for holiday gifts, took their children to see Santa and began counting the days until Christmas – Juanita was required to abandon her home, the latest casualty of Phoenix’s eviction epidemic.