Phoenix Police Department

Audio By Carbonatix

Around 2 p.m. on Jan. 10, Phoenix police officers surrounded a home in Maryvale, a neighborhood on the city’s west side. A lone, shirtless man sat on the roof after running from officers and ditching the handgun that had been holstered to his hip.

Turrell Clay, 33, had an outstanding felony parole violation warrant and was wanted in connection with an armed robbery. From the front and back of the house, officers aimed at Clay with launchers armed with hard plastic projectiles.

A shot struck Clay in the back, knocking him down. Twenty seconds later, officers fired again. Two seconds later, another round. Each time, his upper body fell forward and hit the roof.

Clay sat with his hands up and feet dangling off the roof as an officer shot him again two minutes later. “Get the f- down now. Get the f- down. We’re f–ing done,” the officer yelled as Clay rolled in pain on the edge of the roof. The officer fired again. Clay wailed.

By the time Clay fell from the roof, moaning in pain, police had hit him multiple times with projectiles from the launchers, according to body-camera footage and the police incident report.

“I’m hurt bad, bro,” Clay said in body-camera footage released by the Phoenix Police Department to the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University.

He died four hours later, after complaining of chest pain, while undergoing emergency treatment at a Phoenix hospital. He died a week before his 34th birthday – and his wedding.

In mid-April, the Maricopa County Medical Examiner’s office ruled Clay’s death a homicide, which the examiner’s office defined as “death at the hands of another individual with reasonably inferable intent to do harm.” Clay’s family is seeking $15 million from the city of Phoenix for wrongful death, according to a notice of claim obtained by the Howard Center.

Clay’s death after police struck him with projectiles from less-lethal launchers raises questions about the safety of the munitions Phoenix police classify as “less likely to cause death or Serious Physical Injury than a weapon,” such as a firearm.

“These weapons aren’t inherently safe – their lethality depends on how they’re used,” said Dr. Rohini Haar, an expert on the health effects of less-lethal weapons at the nonprofit Physicians for Human Rights and an emergency physician. “If you shoot someone in the head or from close range, they become more lethal, not less.”

Sage Control Ordnance, Inc., which manufactures the launchers police used against Clay, includes a warning about the projectiles in its technical data: “Shots to the head, neck, thorax, heart and spine can cause death or serious injury.”

Phoenix ramped up the deployment of less-lethal weapons in late 2022 to allow police to resolve situations without using deadly force, which the department defines as force intended to kill or cause serious injury or capable of causing death or serious injury. However, an investigation by the Howard Center found that the weapons have not yet made a significant dent in deadly force shootings.

From 2017 to 2024, Phoenix police shot at, on average, 24 civilians a year. They shot at 25 civilians in 2023 and 20 in 2024. A separate Howard Center analysis of Phoenix police use-of-force incidents, which include all types of police force, also revealed that officers used lethal force against twice as many people in 2023 as they did in 2021, before a decrease in 2024.

The policies about when and how officers should deploy 37 mm four-inch less-lethal launchers, which were used against Clay, are largely kept in restricted tactical plans off limits to the public, the Howard Center learned. The weapons fire plastic projectiles intended to induce “pain compliance.”

Potential injuries from the 37 mm weapons are serious enough, however, that paramedics with the Phoenix Fire Department are always called to evaluate civilians struck with them, according to the narrative in Clay’s police incident report. According to an officer’s account in that report, medics evaluated Clay and told the officer that his “vitals were good” and that none of his injuries required hospitalization. Clay died hours later.

Haar said injuries from less-lethal weapons are hard to detect, in part because the injuries can take time to appear.

“There (are) people whose injuries are missed because it’s blunt trauma, and if you’re not looking, you’re not going to see it,” she said.

When asked for a comment on Clay’s case, the Phoenix Fire Department only referred to an incident log provided by the department. That incident log showed that the department was at that Maryvale home for 52 minutes.

The Phoenix Police Department did not answer the Howard Center’s questions about Clay’s case, or specific questions about the less-lethal launcher program, though it did provide a statement.

“The Phoenix Police Department monitors our less lethal program to make sure the discharges are appropriate and being used within policy,” the department said.

The department also disputed the Howard Center’s finding that the launcher program has so far not lowered the number of police shootings.

“There is no way to measure something that did not happen,” the statement said. “It is impossible to determine the number of more serious police incidents that have been avoided because of the use of less lethal tools.”

Many factors could impact the number of shootings in a given year, the department said. It noted that shootings declined to 20 in 2024, and that 11 of the incidents involved situations in which officers came under gunfire. Several officers were injured in those incidents and one was killed.

Five months after Clay’s death, his family remained unclear about why and how he died. Phoenix police called Clay’s mother the night he died and told family members police used the less-lethal launchers to bring him into custody.

“Regardless of what he was doing, or how he was doing anything, he had people who loved him, and he loved people, and he just had a whole future,” said Larry Lane, Clay’s cousin.

“I just don’t understand how they just continued to hit him,” Lane said. “I just kind of feel like it’s a form of abuse.”

A 40-millimeter foam baton on a table at the Phoenix Regional Police Academy on April 11. When fired, the plastic casing falls while the foam piece is launched from the barrel.

Isabelle Marceles/Howard Center for Investigative Journalism

‘Pain compliance’

Phoenix officers can be trained in more than a dozen types of less-lethal weapons and techniques, from Tasers to powdered irritants shot like paintballs to blows from open or closed fists to restraining devices such as hand and ankle cuffs.

The Howard Center’s investigation focused on two types of launchers used by the Phoenix Police Department for “pain compliance”: the 40 mm and 37 mm. The 37 mm launchers are only used by the department’s tactical teams, which are often deployed to arrest fugitives.

The Phoenix Police Department’s less-lethal training supervisor for the 40 mm, Jake Rasmussen, explained that the weapons are single-shot Penn Arms L140s that fire projectiles made from a dense material that feels like a car tire.

Officers who carry the 40 mm launchers typically have pouches on their belts with two to three additional projectiles, he said. The limited number of projectiles carried and single-shot design forces officers to think before firing the next shot, Rasmussen said.

“We wanted to make sure that there was kind of a pause for some reassessment after force delivery every single time they used it,” he said. “So every single time they launch a projectile out of here, they’ve got to open it up, pull it out, put a new one in.”

After Phoenix police shot at 44 people in 2018, double the number in the year before, then-Chief Jeri Williams announced the department would start tracking every time an officer pointed a firearm at a person, and implemented a policy of publicly releasing video briefings that included some officer-worn body camera footage within 14 days of an officer-involved shooting or other significant use of force.

In October 2021, Phoenix police launched a two-month pilot program to expand deployment of PepperBall launchers and 40 mm launchers to two precincts. “Early indications show this program is proving very successful in preserving life while combating crime,” Williams said in the department’s 2021 end-of-year report. “We also believe less lethal options have contributed to a 50% drop in officer-involved shootings in 2021, from 26 in 2020 to 13 in 2021.”

The U.S. Department of Justice questioned the former chief’s claim in a June 2024 report on the department’s use of force, noting that officers only started using the launchers in the pilot program in late 2021 and that police shootings increased in 2022.

The DOJ’s investigation launched in August 2021. The Phoenix Training Bureau began the less-lethal pilot program in October that year. By November 2022, then-interim Police Chief Michael Sullivan announced training to provide 400 officers with 200 PepperBall launchers and 200 40 mm launchers.

“This tool allows law enforcement the ability to disable or deter threats, resolve situations without lethal force, and accomplish missions while preserving life,” he said.

“This plan revolves around the concept that preservation of life is at the core of policing,” Sullivan said of his package of reforms, including the expansion of officer training in less-lethal tools. “Becoming a self-correcting organization fosters continuous improvement, which allows us to refocus on that core ideal, which is more important now than ever.”

At a Phoenix City Council Public Safety and Justice Subcommittee meeting in December 2023, then-Assistant Police Chief Bryan Chapman said the launchers were for situations involving people armed with weapons other than handguns. They also helped create distance between officers and suspects, giving them more time to de-escalate with “crisis communication,” he said.

Within the next year, in June 2024, the DOJ released a report finding that the department had used excessive and unjustified force and engaged in discriminatory enforcement. The investigation found that Phoenix police frequently used less-lethal weapons against “people who are handcuffed, people in crisis, and people accused of low-level crimes.”

Investigators found that within seconds of arriving on scene, officers fired less-lethal weapons instead of attempting de-escalation tactics, often when force was unnecessary. Officers also continued to use significant force on incapacitated people after they had been critically wounded and shot projectiles to surprise or confuse people with little time for them to follow commands, according to the report.

In May, the DOJ under the Trump administration retracted the department’s investigation into the Phoenix Police Department and retracted or closed investigations into five others. The department also moved to dismiss lawsuits against Louisville and Minneapolis.

Since the DOJ’s June 2024 report, the department has given three official updates to the Phoenix City Council on its improvements. Most significantly, the department in February adopted new use-of-force policies with more detailed guardrails around when and how officers may use lethal and non-lethal force.

For its investigation, the Howard Center examined seven cases involving less-lethal launchers since 2023, when the DOJ had largely completed the investigative phase of its work but before the department’s new use-of-force policies took effect. The cases revealed some of the same practices the DOJ criticized, including using launchers to shoot someone who had already been shot repeatedly with a firearm and was dying.

In one case from 2024, police fired launchers at the wrong person.

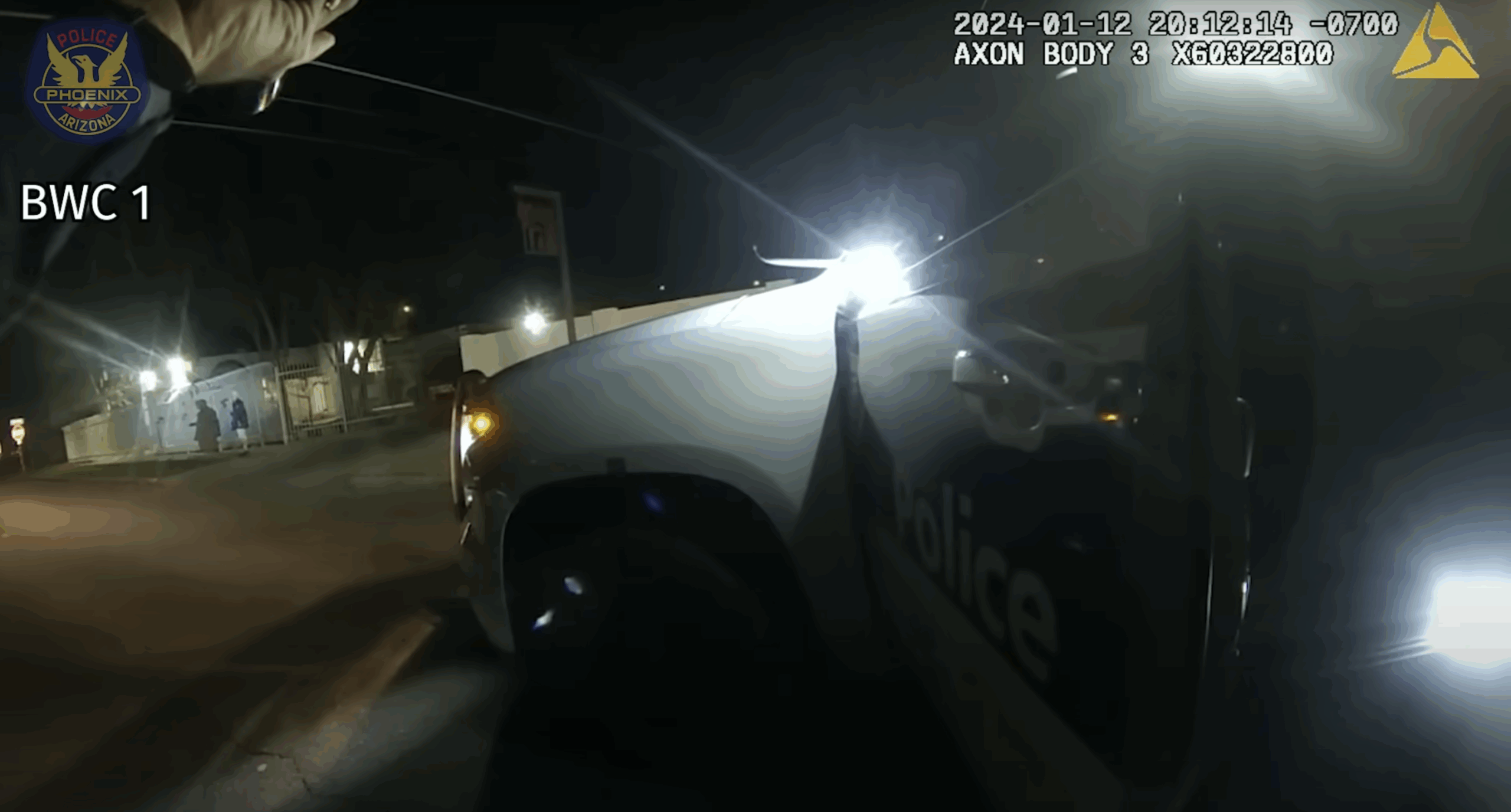

Phoenix police officers approach David Epaloose, an Indigenous man with mental health issues, while trying to find a suspect from a 911 call on Jan. 12, 2023.

Phoenix Police Department

Wrong place, wrong time for Indigenous man

On Jan. 12, 2024, David Epaloose, a 38-year-old Indigenous man with mental health issues, was walking down North 15th Street in Phoenix when police spotted him. Epaloose lived in a nearby affordable housing complex operated by Stepping Stone by Native American Connections.

That evening, a resident had called 911 to report a cousin’s boyfriend kicking at the door. “Right now, he’s banging on the door with a knife,” a man said to a dispatcher around 7:50 p.m. Police officers headed to the scene. Minutes later, a security guard working nearby also called 911.

Officers went looking for the man who had banged on the door. They found Epaloose instead.

He was not an exact match for the suspect, and reports about how closely he matched the description differed. He was carrying an air pistol that shoots BB pellets, not a knife.

Officers ordered Epaloose to stop and show them his hands. When he didn’t comply, officers shot at him at least six times with less-lethal launchers and fired over 100 pepper balls at him. Epaloose ran.

During the chase, police said he turned and pointed the air pistol at them. An officer pulled out a shotgun and hit him with one round. Almost simultaneously, another officer ran him over with his patrol car to stop him. That officer said he believed he had no other choice, according to court records.

“We’re going to have to take him out,” the officer driving the patrol car said in body-camera footage released in the department’s video briefing of the incident.

“He’s reloading,” the officer in the passenger seat said a few seconds later.

“I’m running him over,” the officer driving the patrol car said. “Hold on.”

It wasn’t until Epaloose was taken into custody that detectives realized they had the wrong person. Several days after Epaloose’s arrest, police arrested a man in connection with the case.

Epaloose was left with a broken femur, a brain bleed, a skull fracture and a gunshot wound to his upper left arm. He also found himself facing eight felony charges, including four for aggravated assault against an officer for allegedly pointing the BB gun at police.

Howard Center reporters attended his sentencing on Feb. 4. Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Pamela Dunne sentenced him to six years in prison, with credit for a year already served.

“I died on January 12,” Epaloose said when given the chance to speak at sentencing. “I can’t go to prison for all this.”

Three months later, the court ordered Epaloose to pay $10,000 to cover the medical expenses of the officer who ran him over. The officer said he injured his knee during the incident.

“Being shot by the less-lethal weapons gave me a numbness,” Epaloose said in a text via the messaging system used by the Arizona Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. “I know it was all unfair. … I was shot so much.”

His lawyer, Jason Gronski, declined to speak with a Howard Center reporter when approached for comment at the courthouse.

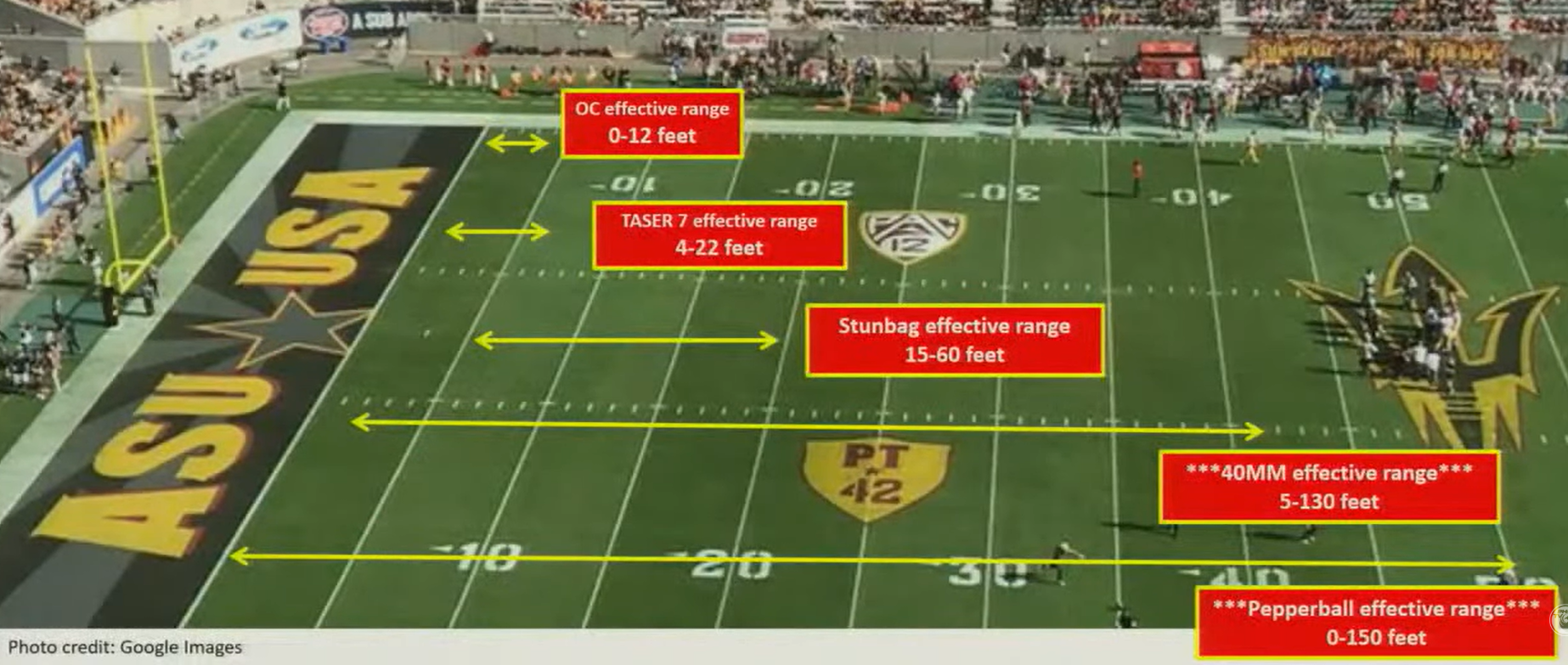

The Phoenix Police Department created a graphic showing the effective firing ranges for different less-lethal weapons for a Phoenix City Council subcommittee meeting in June 2022. A 40 mm launcher is still effective when fired at a target nearly half a football field away.

Phoenix Police Department

Pain and the body’s instinct to flee

Epaloose’s decision to run after being hit with pepper balls and projectiles wasn’t surprising to Haar, the expert from Physicians for Human Rights. Haar said that less-lethal weapons, especially launchers firing chemical irritants, trigger pain receptors that instinctively make the body want to flee.

“The whole point is that these rubber bullets cause pain and make you want to run away,” Haar said. “Tear gas causes pain and makes you want to run away.”

She also said firing less-lethal munitions against people who are experiencing mental health crises is even less effective because they are already in a confused or altered state of mind. Epaloose was schizophrenic, according to statements from his defense attorney in court, but police reports do not indicate if he was experiencing a mental health crisis when officers encountered him.

“If the goal of these weapons … is pain compliance, it’s very hard to get compliance from an individual whose … mental status is altered,” Haar said. “They’re confused. They’re not acting in rational ways, and so getting them to comply with using these weapons doesn’t work very well.”

In these cases, less-lethal force often leads to more agitation and overstimulation, hindering compliance and increasing the risk of injury for people in crisis, Haar said. Police use-of-force expert Michael White, a professor at Arizona State University’s School of Criminology and Criminal Justice and a former deputy sheriff, said training for many police departments emphasizes tactics that fail to de-escalate incidents.

“One of the first things they teach you is that when you get to a scene, immediately establish your control over it,” White said. “That, I think, is inconsistent with some of what we know about good de-escalation.”

Clear communication, active listening and giving the community members the opportunity to tell their stories promote de-escalation, according to White.

The directives for how Phoenix police should deploy the 37 mm launchers that were used against Clay are contained in the Tactical Support Bureau manual, which is restricted. Those for the 40 mm launchers are partly public and partly restricted.

The 37 mm launcher “is used only by our special assignments unit, and that is a tactical unit, and many of their tactical policies are not made public for officer safety as well as community safety,” Donna Rossi, Phoenix Police Department communications director, said in a statement.

Rasmussen, the training supervisor, said he was unaware of any deaths from 40 mm launchers in Phoenix. The department would not confirm if any deaths have been attributed to either kind of launcher.

Rasmussen said the training in Phoenix distinguishes between acceptable and non-acceptable target areas of a suspect’s body, “so that we can ensure, or better ensure, that this is a less-lethal option, and we’re avoiding instances where maybe the likelihood of that serious injury or death might increase.”

The distance between target and non-target areas listed in the Phoenix 40 mm policy is minimal. Officers can aim for the lower abdomen, but not the chest; and for the back or buttucks, but not the spine. They can aim for the legs or arms instead, but have a higher chance of missing. The Phoenix policy authorizes officers to shoot intentionally at non-target areas – including the head, chest, neck and spine – if deadly force is justified.

For a standard 40 mm round, the department’s response options do not include a minimum safe distance for shooting. The policy states the optimal range is between 5 yards and 35 yards. For a high-velocity 40 mm round, the policy states the officer must fire the weapon at least 10 yards from a subject, unless deadly force is justified. Safe distances for 37 mm rounds are not publicly available.

Policies do not specify exactly how many times officers are allowed to shoot the 40 mm launchers during incidents.

“It’s situation dependent, but most of the time, three or four is probably going to do the job,” Rasmussen said. “One or two is probably going to do the job. So you don’t necessarily need more than that.”

A Phoenix police officer attends to Turrell Clay after he was shot with less-lethal launchers in the Phoenix neighborhood of Maryvale on Jan. 10.

Phoenix Police Department

Expert: Injuries are hard to detect

The Howard Center interviewed a man who, in February, was struck by a 37 mm projectile shot by officers from eight feet away as the man said he was trying to surrender, following an undercover drug sale sting.

In the incident report, the Phoenix officer said he shot Christopher Taylor because he thought he might be concealing a weapon in his pants. Officers had already shot the 20-year-old in his backside with a firearm as he fled in an SUV.

“I wouldn’t even know how to describe it,” Taylor said of the impact from the less-lethal projectile, speaking from a Phoenix jail. “It was just pain, pain, and you can’t do nothing about it.”

Taylor said that he did not understand why the officer shot him with the launcher when he was trying to comply.

“I told the cop, I said, ‘Sir, I just got shot – please don’t shoot me,'” Taylor said. “I had my hands up. I turned around. I made sure my hands were super high. They still shot me and said, ‘You gotta get down.'”

Haar, the emergency physician and expert on the effects of less-lethal munitions, said the term “less-lethal” misleads both the public and officers about the dangers of weapons such as 40 mm launchers.

“We try to avoid the use of the word ‘less-lethal,’ because the lethality is pretty much dependent on how these weapons are used,” Haar said.

It’s uncommon, but less-lethal weapons can, and have, killed people, Haar said. And the symptoms – bruising and internal bleeding – are easy to miss or dismiss. A person may be experiencing and voicing all the pain of a fatal injury without any obvious physical signs, she said. Unlike a bullet wound, these injuries are subtle, sometimes not even leaving an immediate bruise, she said.

Haar refrained from commenting on the potential cause of Clay’s death, since the autopsy hasn’t been released, but questioned how he was evaluated.

Clay was sitting in a police car after his arrest, in too much pain to get out when paramedics arrived, according to the police incident report. Paramedics examined him and checked his vitals before deciding he didn’t need further medical attention, and officers were told he had no injuries besides minor abrasions.

Body-worn camera footage from one of the officers shows Clay sitting in the back of a patrol car, visibly distressed and slurring his words.

“Something’s wrong, man,” Clay said to the officer in footage released to The Arizona Republic.

“The Fire Department just came and checked you out, said you’re good,” the officer responded.

Haar was concerned to learn that paramedics cleared Clay based on his vitals and the absence of visible injuries. “If you’re in so much pain that you can’t get out of a car, something is wrong,” Haar said. After paramedics left, according to the police report, Clay also complained to officers that his chest hurt and he had a mark under his left pectoral muscle.

Clay received five medical diagnoses as doctors tried to save his life at a nearby hospital, including a heart attack, a life-threatening heart arrhythmia, fluid buildup around his heart and stimulant abuse. Doctors gave him a cocktail of drugs, including one to prevent blood clots.

His heart stopped during a procedure in a cardiac catheterization lab at the Arizona Heart Hospital. Doctors attempted to restart his heart with two shocks from a defibrillator and CPR.

An officer who examined Clay’s body after he died observed four round, red-purple abrasions under his left nipple, on his left shin, on his inner thigh, and on his tricep.

California native Turrell Clay poses for a portrait. The 33-year-old died in January after he was shot with less-lethal launchers touted by the Phoenix Police Department as a way to reduce officer shootings.

Courtesy of the Clay family

Clay’s family left with few answers

The night Clay died, a Phoenix detective called his family. He shared the details once, then again on a conference call with Clay’s extended family.

“It was just so nonchalant,” said Reginald Sarabia, another cousin. “It was kind of hurtful. I understand that they felt like they were doing their job, but when you’re dealing with somebody’s loved ones …”

Eventually, the detectives stopped answering the family’s calls.

“It’s still hard to this day,” said Lane. “We just lost a big personality, a big person in our family, somebody that I hold dear to me. It just kind of sucks.”

Clay’s family said they didn’t know much about why he had moved to Phoenix, but they knew he wanted to start fresh. Clay grew up in San Bernardino, Calif., and was raised by both his maternal and paternal grandmothers. He was one of seven children. After school as a child, Clay and his cousins, Lane and Sarabia, went to a park near his grandmother’s home and played basketball.

Clay’s first adult interaction with law enforcement came in September 2009, eight months after he turned 18. He was charged with felony vehicle theft and convicted a year later. Over the next 12 years, Clay was hit with a dozen criminal cases, mostly for car theft, burglary and robbery. Some resulted in charges – others were dismissed.

The last time Lane saw Clay, Clay had recently gotten out of prison and was on parole. Clay was going to move to Phoenix with his fiancée, he said.

“He was like, ‘Cuzzo, I’m gonna get out of here, that’s the reason I’m leaving San Bernardino,'” Lane said. “He said, ‘I know if I stay in San Bernardino, I’m gonna be right back in the bull–.'”

Canvassing the Maryvale neighborhood where Clay died, police found a handgun and a bag containing two-thirds of a pound of methamphetamine that Clay hid as he fled police. The gun had one round in the chamber but police did not find a magazine. The officer who confirmed the meth said both the quantity of drugs and the handgun were consistent with someone who dealt drugs.

Clay had many tattoos, according to the police incident report. He had an Air Jordan logo on his cheek and his fiancée’s name on his arm. One of his tattoos, on his chest, was “Psalm 23” – a Bible verse that reads: “Even though I walk through the darkest valley, I will fear no evil, for you are with me; Your rod and your staff, they comfort me.”

Another tattoo, on his arm, read, “Get rich or die trying.”

This story was produced by the students at the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at Arizona State University’s Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, an initiative of the Scripps Howard Foundation in honor of the late news industry executive and pioneer Roy W. Howard.