Photo illustration by Emma Randall; photo by Brandon Bell/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

More than 600 people died of heat-related illnesses in Maricopa County last year, the second-highest total in history. For that, the city of Phoenix has been taking a victory lap.

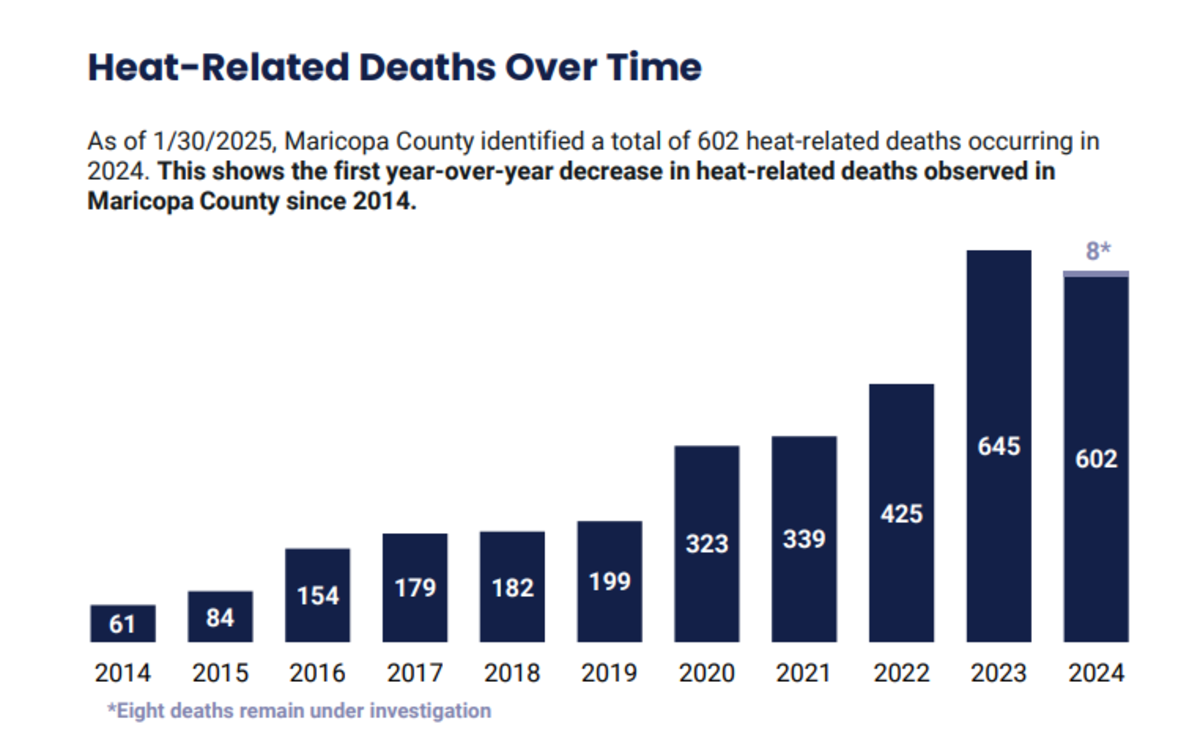

On March 10, the Maricopa County Department of Public Health released preliminary data chronicling heat-related deaths and illnesses for 2024. The headline – as framed by the county, city and several media reports – was a positive one. For the first time in more than a decade, the number of people who died from the Valley’s unforgiving heat decreased year over year.

A journey of a thousand miles begins with a small step, of course, but largely unhighlighted was how small that step was. The county health department reported 602 heat deaths from 2024, with another eight still under investigation. That means, at best, heat deaths dropped by 5.4% since 2023, when 645 people died. That grisly death toll represented a jump of 52% over 2022.

Maricopa County Department of Public Health

In Phoenix, that dip was cause for celebration and back-patting. The city had geared up to combat the heat in 2024, opening more cooling centers and expanding their hours. As a result, city officials asserted, they had successfully bent the curve in the other direction, as slight as the downward arc may appear.

“No deaths are acceptable, and we’ll continue to work to ensure our most vulnerable residents, including those experiencing homelessness, have shelter and heat relief options during our extreme summer heat,” Mayor Kate Gallego said in a press release. “But these numbers show that we’re having an impact, we’re making a difference, and we’re saving lives.”

Phoenix city councilmembers echoed her optimism. Debra Stark said the city’s heat mitigation initiatives saved lives. “I hope this is the beginning of a downward trend of heat-related fatalities,” she said. Councilmember Carlos Galindo-Elvira said the dip in deaths “is a direct result of Phoenix’s investment in resources for the unhoused.” Ann O’Brien, the vice mayor, tossed plaudits at Gallego.

“Through successful policymaking and with thanks to Mayor Gallego’s leadership, we were able to see a significant reduction in heat-related deaths,” O’Brien said.

With more than 600 deaths, your definition of “significant” may vary.

Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego said a small dip in heat deaths in 2024 shows “we’re making a difference, and we’re saving lives.”

Jaron Quach

Cooling centers

There’s no denying that Phoenix made a concerted effort to address the heat last summer. The shocking spike in deaths in 2023 – the result of soaring evictions, increased homelessness and 31 straight days with temperatures reaching 110 degrees – caught Phoenix off guard. In a press release, Gallego’s office said the city spent about $3 million on summer heat relief services last year.

Much of that went toward expanding the hours of the five Phoenix-set cooling centers, where people can escape the heat. In previous years, the cooling centers closed at 5 or 6 p.m., which is often the hottest part of the day. Last year they closed at 10 p.m. Two libraries also served as overnight shelters, each with space for 50 people. Phoenix was the only city to offer overnight shelters. In total, the city said it logged more than 28,000 visits at its cooling centers.

“With a coordinated countywide strategy, nearly every one of these deaths can be prevented,” Rebecca Sunenshine, the health department’s medical director, said in a press release.

If preventing “nearly every single one of these deaths” is the goal, though, Phoenix and the county have a long way to go. Even if the county were to repeat its year-over-year success every year going forward – namely, a yearly 5% drop in heat deaths – it would take seven years to reach the 2023 total of 425, which currently stands as the third-highest total ever recorded.

Just keeping up last year’s efforts will require a funding challenge. The expanded cooling center hours were only possible thanks to funding from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, which allocated special emergency funding for local governments. Those funds are set to expire.

A year ago, Sunenshine said the county had “not yet identified a sustainable way to fund these activities in future heat seasons” because “there just aren’t a lot of grants out there for health departments to apply for heat relief.” But in a March 10 press release, the county health department said the expanded cooling center hours would be funded this year.

Department spokespersons Sonia Singh and Courtney Kreuzweisner have not responded to questions about the funding. Gallego’s office said Phoenix will need to support the cooling centers with money from the city’s own general fund, though the mayor repeated a call for other levels of government to step up.

“Extreme heat must be treated as a public health emergency by every level of government, and that’s not the case yet,” Gallego said. “We need more support from the federal and state governments, and other cities will need to step up and expand heat relief in their communities.”

Homeless advocate Elizabeth Venable is confident the cooling centers did make a difference. “I believe they are critical,” she said. She’s also confident the council will make an effort to fund them again. “I think they’ll make these investments because they create a cost-savings to the city of Phoenix because they reduce the burden on law enforcement, fire, emergency calls – a wide variety of systems,” Venable said.

Extreme heat is a “force multiplier,” said county chief medical officer Dr. Nick Staab.

Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

A mirage?

One critic is skeptical of the city’s self-congratulatory tone. On X, public relations consultant Stacey Champion claimed the county’s heat deaths number was “absolute bullshit” and that local officials are eager to accept the preliminary report’s slight drop in deaths as certain. Champion can’t back her hunch up with data yet, though, because the county hadn’t fulfilled a public records request she made to find out.

“For the city or the county to take some victory lap is absolutely insane,” Champion told New Times in a phone interview. “If you look at last year’s numbers, it far surpasses years prior and heat deaths are notoriously undercounted. I mean, it’s called the silent killer.”

Champion’s argument is that heat-related deaths tend to go undercounted. “Heat is a force multiplier,” said Dr. Nick Staab, the county health department’s chief medical officer, in a press release. Heat exacerbates underlying health conditions like cardiac issues, Champion said, and some doctors may not think to list heat as a contributing factor in some cases, as was found to be the case in Texas last year.

Will Humble, the executive director of the nonprofit Arizona Public Health Association, thinks the city’s broadcasted dip in deaths isn’t worth “splitting hairs” over. “There’s always going to be some noise in the cause of death because individual doctors are making their determination on the cause of death,” he said. Yet Humble also noted that heat deaths are as bad as ever.

“We know enough that it’s bad and it’s gotten a lot worse,” he said, “even if it didn’t get demonstrably worse this year.”

Humble thinks officials are leaving the biggest possible heat mitigation strategy unaddressed. While heat relief and water stations are great, he said deaths won’t meaningfully decline if the Valley’s cities don’t get serious about the area’s lack of housing for poor and unhoused people.

People experiencing homelessness made up 50% of confirmed heat-related deaths last year. Last year, he wrote that a total of 7,182 unhoused people in the county were categorized as having a serious mental illness, which makes housing harder to obtain.

“Almost never do you hear about the lack of supportive housing – not even affordable housing – for people enrolled in Medicaid with a serious mental illness,” Humble said. “They’ll wait six months to two years, and that leads to homelessness in the summer, which leads to the deaths.”

Solutions of that magnitude are on Humble’s wish list, though it doesn’t seem to be on the table just now. The Phoenix City Council is set to discuss funding heat relief measures, like the cooling centers, in a Tuesday meeting.

If Phoenix and the county really want to brag about preventing heat deaths, drastically expanding housing is what it will take. Otherwise, Humble said, “you’re never going to make a dent.”